This is the third of three posts summarizing what I learned when I interviewed 17 AI safety experts about their "big picture" of the existential AI risk landscape: how AGI will play out, how things might go wrong, and what the AI safety community should be doing. See here for a list of the participants and the standardized list of questions I asked.

This post summarizes the responses I received from asking “Are there any big mistakes the AI safety community has made in the past or are currently making?”

“Yeah, probably most things people are doing are mistakes. This is just some random group of people. Why would they be making good decisions on priors? When I look at most things people are doing, I think they seem not necessarily massively mistaken, but they seem somewhat confused or seem worse to me by like 3 times than if they understood the situation better.” - Ryan Greenblatt

“If we look at the track record of the AI safety community, it quite possibly has been harmful for the world.” - Adam Gleave

“Longtermism was developed basically so that AI safety could be the most important cause by the utilitarian EA calculus. That's my take.” - Holly Elmore

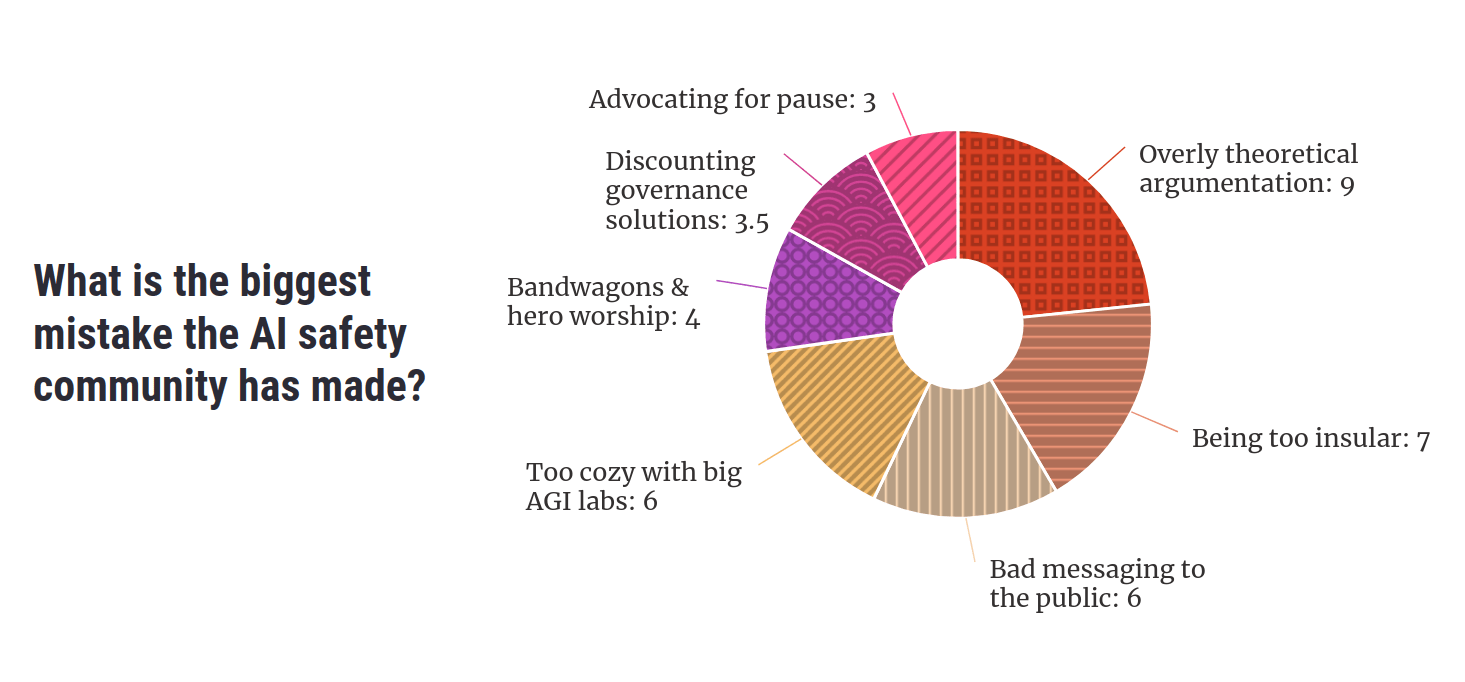

Participants pointed to a range of mistakes they thought the AI safety movement had made. Key themes included an overreliance on theoretical argumentation, being too insular, putting people off by pushing weird or extreme views, supporting the leading AGI companies, insufficient independent thought, advocating for an unhelpful pause to AI development, and ignoring policy as a potential route to safety.

How to read this post

This is not a scientific analysis of a systematic survey of a representative sample of individuals, but my qualitative interpretation of responses from a loose collection of semi-structured interviews. Take everything here with the appropriate seasoning.

Results are often reported in the form “N respondents held view X”. This does not imply that “17-N respondents disagree with view X”, since not all topics, themes and potential views were addressed in every interview. What “N respondents held view X” tells us is that at least N respondents hold X, and consider the theme of X important enough to bring up.

The following is a summary of the main themes that came up in my interviews. Many of the themes overlap with one another, and the way I’ve clustered the criticisms is likely not the only reasonable categorization.

Too many galaxy-brained arguments & not enough empiricism

“I don't find the long, abstract style of investigation particularly compelling.” - Adam Gleave

9 respondents were concerned about an overreliance or overemphasis on certain kinds of theoretical arguments underpinning AI risk: namely Yudkowsky’s arguments in the sequences and Bostrom’s arguments in Superintelligence.

“All these really abstract arguments that are very detailed, very long and not based on any empirical experience. [...]

Lots of trust in loose analogies, thinking that loose analogies let you reason about a topic you don't have any real expertise in. Underestimating the conjunctive burden of how long and abstract these arguments are. Not looking for ways to actually test these theories. [...]

You can see Nick Bostrom in Superintelligence stating that we shouldn't use RL to align an AGI because it trains the AI to maximize reward, which will lead to wireheading. The idea that this is an inherent property of RL is entirely mistaken. It may be an empirical fact that certain minds you train with RL tend to make decisions on the basis of some tight correlate of their reinforcement signal, but this is not some fundamental property of RL.”

- Alex Turner

Jamie Bernardi argued that the original view of what AGI will look like, namely an RL agent that will reason its way to general intelligence from first principles, is not the way things seem to be panning out. The cutting-edge of AI today is not VNM-rational agents who are Bayesianly-updating their beliefs and trying to maximize some reward function. The horsepower of AI is instead coming from oodles of training data. If an AI becomes power-seeking, it may be because it learns power-seeking from humans, not because of instrumental convergence!

There was a general sense that the way we make sense of AI should be more empirical. Our stories need more contact with the real world – we need to test and verify the assumptions behind the stories. While Adam Gleave overall agreed with this view, he also warned that it’s possible to go too far in the other direction, and that we must strike a balance between the theoretical and the empirical.

Problems with research

This criticism of “too much theoretical, not enough empirical” also applied to the types of research we are doing. 4 respondents focussed on this. This was more a complaint about past research, folks were typically more positive about the amount of empirical work going on now.

2 people pointed at MIRI’s overreliance on idealized models of agency in their research, like AIXI. Adrià Garriga-Alonso thought that infrabayesianism, parts of singular learning theory and John Wentworth’s research programs are unlikely to end up being helpful for safety:

“I think the theory-only projects of the past did not work that well, and the current ones will go the same way.” - Adrià Garriga-Alonso

Evan Hubinger pushed back against this view by defending MIRI’s research approach. He pointed out that, when a lot of this very theoretical work was being done, there wasn’t much scope to do more empirical work because we had no highly capable general-purpose models to do experiments on – theoretical work was the best we could do!

“Now it's very different. Now, I think the best work to do is all empirical. Empirical research looks really good right now, but it looked way less good three, four years ago. It's just so much easier to do good empirical work now that the models are much smarter.” - Evan Hubinger

Too insular

8 participants thought AI safety was too insular: the community has disvalued forming alliances with other groups and hasn’t integrated other perspectives and disciplines.

2 of the 8 focussed on AI safety’s relationship with AI ethics. Many in AI safety have been too quick to dismiss the concerns of AI ethicists that AI could exacerbate current societal problems like racism, sexism and concentration of power, on the grounds of extinction risk being “infinitely more important”. But AI ethics has many overlaps with AI safety both technically and policy:

“Many of the technical problems that I see are the same. If you're trying to align a language model, preventing it from saying toxic things is a great benchmark for that. In most cases, the thing we want on an object level is the same! We want more testing of AI systems, we want independent audits, we want to make sure that you can't just deploy an AI system unless it meets some safety criteria.” - Adam Gleave

In environmentalism, some care more about the conservation of bird species, while others are more concerned about preventing sea level rise. Even though these two groups may have different priorities, they shouldn’t fight because they have agree on many important subgoals, and have many more priorities in common with each other than with, for example, fossil fuel companies. Building a broader coalition could be similarly important for AI safety.

Another 2 respondents argued that AI safety needs more contact with academia. A big fraction of AI safety research is only shared via LessWrong or the Alignment Forum rather than academic journals or conferences. This can be helpful as it speeds up the process of sharing research by sidestepping “playing the academic game” (e.g. tuning your paper to fit into academic norms), but has the downside that research typically receives less peer review, leading to on average lower quality posts on sites like LessWrong. Much of AI safety research lacks the feedback loops that typical science has. AI safety also misses out on the talent available in the broader AI & ML communities.

Many of the computer science and math kids in AI safety do not value insights from other disciplines enough, 2 respondents asserted. Gillian Hadfield argued that many AI safety researchers are getting norms and values all wrong because we don’t consult the social sciences. For example: STEM people often have an assumption that there are some norms that we can all agree on (that we call “human values”), because it’s just “common sense”. But social scientists would disagree with this. Norms and values are the equilibria of interactions between individuals, produced by their behaviors, not some static list of rules up in the sky somewhere.

Another 2 respondents accused the rationalist sphere of using too much jargony and sci-fi language. Esoteric phrases like “p(doom)”, “x-risk” or “HPMOR” can be off-putting to outsiders and a barrier to newcomers, and give culty vibes. Noah conceded that shorthands can be useful to some degree (for example they can speed up idea exchange by referring to common language rather than having to re-explain the same concept over and over again), but thought that on the whole AI safety has leaned too much in the jargony direction.

Ajeya Cotra thought some AI safety researchers, like those at MIRI, have been too secretive about the results of their research. They do not publish their findings due to worries that a) their insights will help AI developers build more capable AI, and b) they will spread AGI hype and encourage more investment into building AGI (although Adam considered that creating AI hype is one of the big mistakes AI safety has made, on balance he also thought many groups should be less secretive). If a group is keeping their results secret, this is in fact a sign that they aren’t high quality results. This is because a) the research must have received little feedback or insights from other people with different perspectives, and b) if there were impressive results, there would be more temptation to share it.

Holly Elmore suspected that this insular behavior was not by mistake, but on purpose. The rationalists wanted to only work with those who see things the same way as them, and avoid too many “dumb” people getting involved. She recalled conversations with some AI safety people who lamented that there are too many stupid or irrational newbies flooding into AI safety now, and the AI safety sphere isn't as fun as it was in the past.

Bad messaging

“As the debate becomes more public and heated, it’s easy to fall into this trap of a race to the bottom in terms of discourse, and I think we can hold better standards. Even as critics of AI safety may get more adversarial or lower quality in their criticism, it’s important that we don’t stoop to the same level. [...] Polarization is not the way to go, it leads to less action.” - Ben Cottier

6 respondents thought AI safety could communicate better with the wider world. The AI safety community do not articulate the arguments for worrying about AI risk well enough, come across as too extreme or too conciliatory, and lean into some memes too much or not enough.

4 thought that some voices push views that are too extreme or weird (but one respondent explicitly pushed against this worry). Yudkowsky is too confident that things will go wrong, and PauseAI is at risk of becoming off-putting if they continue to lean into the protest vibe. Evan thought Conjecture has been doing outreach badly – arguing against sensible policy proposals (like responsible scaling policies) because they don’t go far enough. David Krueger however leaned in the opposite direction: he thought that we are too scared to use sensationalist language like “AI might take over”, while in fact, this language is good for getting attention and communicating concerns clearly.

Ben Cottier lamented the low quality of discourse around AI safety, especially in places like Twitter. We should have a high standard of discourse, show empathy to the other side of the debate, and seek compromises (with e.g. open source advocates). The current bad discourse is contributing to polarization, and nothing gets done when an issue is polarized. Ben also thought that AI safety should have been more prepared for the “reckoning moment” of AI risk becoming mainstream, so we had more coherent articulations of the arguments and reasonable responses to the objections.

Some people say that we shouldn’t anthropomorphize AI, but Nora Belrose reckoned we should do it more! Anthropomorphising makes stories much more attention-grabbing (it is “memetically fit”). One of the most famous examples of AI danger has been Sydney: Microsoft’s chatbot that freaked people out by being unhinged in a very human way.

AI safety’s relationship with the leading AGI companies

“Is it good that the AI safety community has collectively birthed the three main AI orgs, who are to some degree competing, and maybe we're contributing to the race to AGI? I don’t know how true that is, but it feels like it’s a little bit true.

If the three biggest oil companies were all founded by people super concerned about climate change, you might think that something was going wrong.”

- Daniel Filan

Concern for AI safety had at least some part to play in the founding of OpenAI, Anthropic and DeepMind. Safety was a stated primary concern that drove the founding of OpenAI. Anthropic was founded by researchers who left OpenAI because it wasn’t sufficiently safety-conscious. Shane Legg, one of DeepMind’s co-founders, is on record for being largely motivated by AI safety. Their existence is arguably making AGI come sooner, and fuelling a race that may lead to more reckless corner-cutting in AI development. 5 respondents thought the existence of these three organizations is probably a bad thing.

Jamie thought the existence of OpenAI may be overall positive though, due to their strategy of widely releasing models (like ChatGPT) to get the world experienced with AI. ChatGPT has thrust AI into the mainstream and precipitated the recent rush of interest in the policy world.

3 respondents also complained that the AI safety community is too cozy with the big AGI companies. A lot of AI safety researchers work at OpenAI, Anthropic and DeepMind. The judgments of these researchers may be biased by a conflict of interest: they may be incentivised for their company to succeed in getting to AGI first. They will also be contractually limited in what they can say about their (former) employer, in some cases even for life.

Adam recommended that AI safety needs more voices who are independent of corporate interests, for example in academia. He also recommended that we shouldn’t be scared to criticize companies who aren’t doing enough for safety.

While Daniel Filan was concerned about AI safety’s close relationship with these companies, he conceded that there must be a balance between inside game (changing things from the inside) and outside game (putting pressure on the system from the outside). AI safety is mostly playing the inside game – get involved with the companies who are causing the problem, to influence them to be more careful and do the right thing. In contrast, the environmentalism movement largely plays an outside game – not getting involved with oil companies but protesting them from the outside. Which of these is the right way to make change happen? Seems difficult to tell.

The bandwagon

“I think there's probably lots of people deferring when they don't even realize they're deferring.” - Ole Jorgensen

Many in the AI safety movement do not think enough for themselves, 4 respondents thought. Some are too willing to adopt the views of a small group of elites who lead the movement (like Yudkowsy, Christiano and Bostrom). Alex Turner was concerned about the amount of “hero worship” towards these thought leaders. If this small group is wrong, then the entire movement is wrong. As Jamie pointed out, AI safety is now a major voice in the AI policy world – making it even more concerning that AI safety is resting on the judgements of such a small number of people.

“There's maybe some jumping to like: what's the most official way that I can get involved in this? And what's the community-approved way of doing this or that? That's not the kind of question I think we should be asking.” - Daniel Filan

Pausing is bad

3 respondents thought that advocating for a pause to AI development is bad, while 1 respondent was pro-pause[1]. Nora referred me to a post she wrote arguing that pausing is bad. In that post, she argues that pausing will a) reduce the quality of alignment research because researchers will be forced to test their ideas on weak models, b) make a hard takeoff more likely when the pause is lifted, and c) push capabilities research underground, where regulations are looser.

Discounting public outreach & governance as a route to safety

Historically, the AI safety movement has underestimated the potential of getting the public on-side and getting policy passed, 3 people said. There is a lot of work in AI governance these days, but for a long time most in AI safety considered it a dead end. The only hope to reduce existential risk from AI was to solve the technical problems ourselves, and hope that those who develop the first AGI implement them. Jamie put this down to a general mistrust of governments in rationalist circles, not enough faith in our ability to solve coordination problems, and a general dislike of “consensus views”.

Holly thought there was a general unconscious desire for the solution to be technical. AI safety people were guilty of motivated reasoning that “the best way to save the world is to do the work that I also happen to find fun and interesting”. When the Singularity Institute pivoted towards safety and became MIRI, they never gave up on the goal of building AGI – just started prioritizing making it safe.

“Longtermism was developed basically so that AI safety could be the most important cause by the utilitarian EA calculus. That's my take.” - Holly Elmore

She also condemned the way many in AI safety hoped to solve the alignment problem via “elite shady back-room deals”, like influencing the values of the first AGI system by getting into powerful positions in the relevant AI companies.

Richard Ngo gave me similar vibes, arguing that AI safety is too structurally power-seeking: trying to raise lots of money, trying to gain influence in corporations and governments, trying to control the way AI values are shaped, favoring people who are concerned about AI risk for jobs and grants, maintaining the secrecy of information, and recruiting high school students to the cause. We can justify activities like these to some degree, but Richard worried that AI safety was leaning too much in this direction. This has led many outside of the movement to deeply mistrust AI safety (for example).

“From the perspective of an external observer, it’s difficult to know how much to trust stated motivations, especially when they tend to lead to the same outcomes as deliberate power-seeking.” - Richard Ngo

Richard thinks that a better way for AI safety to achieve its goals is to instead gain more legitimacy by being open, informing the public of the risks in a legible way, and prioritizing competence.

More abstractly, both Holly and Richard reckoned that there is too much focus on individual impact in AI safety and not enough focus on helping the world solve the problem collectively. More power to do good lies in the hands of the public and governments than many AI safety folk and effective altruists think. Individuals can make a big difference by playing 4D chess, but it’s harder to get right and often backfires.

“The agent that is actually having the impact is much larger than any of us, and in some sense, the role of each person is to facilitate the largest scale agent, whether that be the AI safety community or civilization or whatever. Impact is a little meaningless to talk about, if you’re talking about the impact of individuals in isolation.” - Richard Ngo

Conclusion

Participants pointed to a range of mistakes they thought the AI safety movement had made. An overreliance on overly theoretical argumentation, being too insular, putting the public off by pushing weird or extreme views, supporting the leading AGI companies, not enough independent thought, advocating for an unhelpful pause to AI development, and ignoring policy as potential a route to safety.

Personally, I hope this can help the AI safety movement avoid making similar mistakes in the future! Despite the negative skew of my questioning, I walked away from these conversations feeling pretty optimistic about the direction the movement is heading. I believe that as long as we continue to be honest, curious and open-minded about what we’re doing right and wrong, AI safety as a concept will overall have a positive effect on humanity’s future.

- ^

Other respondents may also have been pro or anti-pause, but since the pause debate did not come up in their interviews I didn’t learn what their positions on this issue were.

Link seems to be missing

fixed, thanks!

Executive summary: The AI safety community has made several mistakes, including overreliance on theoretical arguments, insularity, pushing extreme views, supporting leading AGI companies, insufficient independent thought, advocating for an AI development pause, and discounting policy as a route to safety.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.