Matthew_Barnett

Posts 24

Comments418

I could sympathize with the frustration, but I feel like I'm being attacked in a way that's pretty unfair.

Sorry if my previous comment came across as rude or harsh—that wasn't my intention. I didn't mean to attack you. I asked those questions to clarify your exact claim because I wanted to understand it fully and potentially challenge it depending on its interpretation. My intent was for constructive disagreement, not criticism of you personally.

I find your other papers you linked in other comments interesting. That said, I don't see them changing my main argument much.

Your main argument started with and seemed to depend heavily on the idea that inequality has been increasing. If it turns out that this key assumption is literally incorrect, then it seems like that should significantly affect your argument.

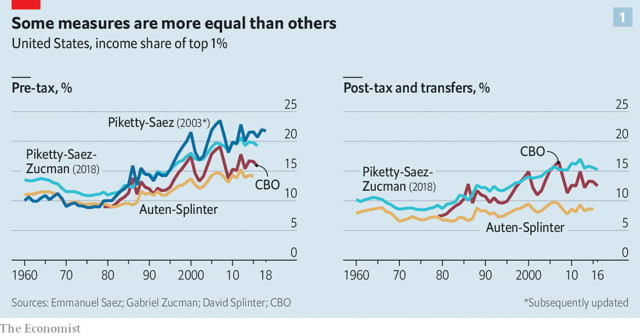

Your point about the top 1%'s rising income share uses pre-tax and transfers data, which can be misleading here because the discussion is specifically about how much income rich people actually control and can redirect towards their desired ends. Post-tax and transfer measures are more informative in this context since they directly reflect the resources individuals genuinely have available after taxes and redistribution. In other words, taxes and transfers matter because they substantially reduce the actual amount of wealth the rich can freely use, donate, or influence society with. Ignoring this gives a distorted picture of how much power or control rich people practically possess, which is central to the original discussion.

Other studies have notably not found meaningful increases in the top 1%'s income share after taxes and transfers are taken into account:

It's worth noting that much of the reported increase in wealth inequality since 1989 seems to be explained by the rising share of wealth held via social insurance programs. Catherine et al. notes,

Recent influential work finds large increases in inequality in the U.S. based on measures of wealth concentration that notably exclude the value of social insurance programs. This paper shows that top wealth shares have not changed much over the last three decades when Social Security is properly accounted for. This is because Social Security wealth increased substantially from $7 trillion in 1989 to $39 trillion in 2019 and now represents 49% of the wealth of the bottom 90% of the wealth distribution. This finding is robust to potential changes to taxes and benefits in response to system financing concerns.

Since both ordinary private wealth and social insurance programs are similar in that they provide continuous streams of income to people, I think it's likely misleading to suggest that wealth inequality has gone up meaningfully in recent decades in the United States—at least based on the reported datasets that presently exist.

Social insurance income streams are especially relevant in this context because they directly affect how much real economic power and control people have in practice. Ignoring social insurance thus exaggerates how concentrated real economic power actually is, since it underestimates the resources available to the broader population.

That said, inequality statistics are quite contentious in general given the lack of reliable data on the exact variables we care about, so I'm not highly confident in this picture. Ultimately I'm unsure whether inequality has remained roughly constant over the last few decades in the sense we should care about.

It seems like recently (say, the last 20 years) inequality has been rising.

When you say inequality has been rising, do you mean income inequality or wealth inequality? What's your source for this claim?

[Edit: reworded to be less curt and harsh]

I tentatively agree with your statement that,

To me, it seems much more likely that Earth-originating intelligence will go extinct this century than, say, in the 8973th century AD.

That said, I still suspect the absolute probability of total extinction of intelligent life during the 21st century is very low. To be more precise, I'd put this probability at around 1% (to be clear: I recognize other people may not agree that this credence should count as "extremely low" or "very low" in this context). To justify this statement, I would highlight several key factors:

- Throughout hundreds of millions of years, complex life has demonstrated remarkable resilience. Since the first vertebrates colonized land during the late Devonian period (approximately 375–360 million years ago), no extinction event has ever eradicated all species capable of complex cognition. Even after the most catastrophic mass extinctions, such as the end-Permian extinction and the K-Pg extinction, vertebrates rebounded. Not only did they recover, but they also surpassed their previous levels of ecological dominance and cognitive complexity, as seen in the increasing brain size and adaptability of various species over time.

- Unlike non-intelligent organisms, intelligent life—starting with humans—possesses advanced planning abilities and an exceptional capacity to adapt to changing environments. Humans have successfully settled in nearly every climate and terrestrial habitat on Earth, from tropical jungles to arid deserts and even Antarctica. This extreme adaptability suggests that intelligent life is less vulnerable to complete extinction compared to other complex life forms.

- As human civilization has advanced, our species has become increasingly robust against most types of extinction events rather than more fragile. Technological progress has expanded our ability to mitigate threats, whether they come from natural disasters or disease. Our massive global population further reduces the likelihood that any single event could exterminate every last human, while our growing capacity to detect and neutralize threats makes us better equipped to survive crises.

- History shows that even in cases of large-scale violence and genocide, the goal has almost always been the destruction of rival groups—not the annihilation of all life, including the perpetrators themselves. This suggests that intelligent beings have strong instrumental reasons to avoid total extinction events. Even in scenarios involving genocidal warfare, the likelihood of all intelligent beings willingly or accidentally destroying all life—including their own—seems very low.

- I have yet to see any compelling evidence that near-term or medium-term technological advancements will introduce a weapon or catastrophe capable of wiping out all forms of intelligent life. While near-term technological risks certainly exist that threaten human life, none currently appear to pose a credible risk of total extinction of intelligent life.

- Some of the most destructive long-term technologies—such as asteroid manipulation for planetary bombardment—are likely to develop alongside technologies that enhance our ability to survive and expand into space. As our capacity for destruction grows, so too will our ability to establish off-world colonies and secure alternative survival strategies. This suggests that the overall trajectory of intelligent life seems to be toward increasing resilience, not increasing vulnerability.

- Artificial life could rapidly evolve to become highly resilient to environmental shocks. Future AIs could be designed to be at least as robust as insects—able to survive in a wide range of extreme and unpredictable conditions. Similar to plant seeds, artificial hardware could be engineered to efficiently store and execute complex self-replicating instructions in a highly compact form, enabling them to autonomously colonize diverse environments by utilizing various energy sources, such as solar and thermal energy. Having been engineered rather than evolved naturally, these artificial systems could take advantage of design principles that surpass biological organisms in adaptability. By leveraging a vast array of energy sources and survival strategies, they could likely colonize some of the most extreme and inhospitable environments in our solar system—places that even the most resilient biological life forms on Earth could never inhabit.

In my comment I later specified "in [the] next century" though it's quite understandable if you missed that. I agree that eventual extinction of Earth-originating intelligent life (including AIs) is likely; however, I don't currently see a plausible mechanism for this to occur over time horizons that are brief by cosmological standards.

(I just edited the original comment to make this slightly clearer.)

In my view, the extinction of all Earth-originating intelligent life (including AIs) seems extremely unlikely over the next several decades. While a longtermist utilitarian framework takes even a 0.01 percentage point reduction in extinction risk quite seriously, there appear to be very few plausible ways that all intelligent life originating from Earth could go extinct in the next century. Ensuring a positive transition to artificial life seems more useful on current margins.

That makes sense. For what it’s worth, I’m also not convinced that delaying AI is the right choice from a purely utilitarian perspective. I think there are reasonable arguments on both sides. My most recent post touches on this topic, so it might be worth reading for a better understanding of where I stand.

Right now, my stance is to withhold strong judgment on whether accelerating AI is harmful on net from a utilitarian point of view. It's not that I think a case can't be made: it's just I don’t think the existing arguments are decisive enough to justify a firm position. In contrast, the argument that accelerating AI benefits people who currently exist seems significantly more straightforward and compelling to me.

This combination of views leads me to see accelerating AI as a morally acceptable choice (as long as it's paired with adequate safety measures). Put simply:

- When I consider the well-being of people who currently exist, the case for acceleration appears fairly strong and compelling.

- When I take an impartial utilitarian perspective—one that prioritizes long-term outcomes for all sentient beings—the arguments for delaying AI seem weak and highly uncertain.

Since I give substantial weight to both perspectives, the stronger and clearer case for acceleration (based on the interests of people alive today) outweighs the much weaker and more uncertain case for delay (based on speculative long-term utilitarian concerns) in my view.

Of course, my analysis here doesn’t apply to someone who gives almost no moral weight to the well-being of people alive today—someone who, for instance, would be fine with everyone dying horribly if it meant even a tiny increase in the probability of a better outcome for the galaxy a billion years from now. But in my view, this type of moral calculus, if taken very seriously, seems highly unstable and untethered from practical considerations.

Since I think we have very little reliable insight into what actions today will lead to a genuinely better world millions of years down the line, it seems wise to exercise caution and try to avoid overconfidence about whether delaying AI is good or bad on the basis of its very long-term effects.

I think it's extremely careless and condemnable to impose this risk on humanity just because you have personally deemed it acceptable.

I'm not sure I fully understand this criticism. From a moral subjectivist perspective, all moral decisions are ultimately based on what individuals personally deem acceptable. If you're suggesting that there is an objective moral standard—something external to individual preferences—that we are obligated to follow, then I would understand your point.

That said, I’m personally skeptical that such an objective morality exists. And even if it did, I don’t see why I should necessarily follow it if I could instead act according to my own moral preferences—especially if I find my own preferences to be more humane and sensible than the objective morality.

This would be a deontological nightmare. Who gave AI labs the right to risk the lives of 8 billion people?

I see why a deontologist might find accelerating AI troublesome, especially given their emphasis on act-omission asymmetry—the idea that actively causing harm is worse than merely allowing harm to happen. However, I don’t personally find that distinction very compelling, especially in this context.

I'm also not a deontologist: I approach these questions from a consequentialist perspective. My personal ethics can be described as a mix of personal attachments and broader utilitarian concerns. In other words, I both care about people who currently exist, and more generally about all morally relevant beings. So while I understand why this argument might resonate with others, it doesn’t carry much weight for me.

Using the data cited in your source (the Distributional Financial Accounts (DFA) provided by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors), it seems to me that the growth in the share of wealth held by the top 0.1% has not been very fast in the last 20 years—growing from around 10-11% to around 14% over that period. In my opinion, this is a significant, albeit rather unimportant trend relative to other social shifts in the last 20 years.

Moreover, this data does not include wealth held in social insurance programs (as I pointed out in another comment). If included, this would presumably decrease the magnitude of the trend seen in this plot, especially regarding the declining share of wealth held by the bottom 90%.