Last week I donated a kidney as an altruistic donor through the UK Living Kidney Sharing Scheme (UKLKSS). This post will cover the landscape of kidney donation in the UK, how kidneys from living donors are shared in the UK, the process of donating through the UKLKSS, and some reflections on my experience.

Note: this post discusses details of altruistic kidney donation specifically in the context of the UK.

Kidney donation in the UK

At any one time, some 3,500-5,000 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) sit on the UK’s national waiting list in need of a kidney donation. While most of these are adults, 112 children (under 18 years of age) were in need of a replacement kidney in April 2021 (most recent data available). While waiting for a replacement kidney, these individuals must undergo renal dialysis for three to four hours per session, three times every week, which imposes severe limitations on the freedom in their lives and their ability to enjoy a ‘normal’ existence. Around 250 of these people die every year, either because a suitable donor cannot be identified in time, or after they are removed from the waiting list due to a deterioration in their health that renders them no longer able to endure the necessary surgery and immunosuppressive therapies inherent to organ transplantation.

Around 3,000 kidney donations take place in the UK each year, of which about 2,000 originate from deceased donors (an opt-out system of organ donation after death came into effect in Wales in 2015, in England in 2020, and in Scotland in 2021, and Northern Ireland will follow suit in 2023), and about 1,000 from living donors. Kidneys constitute by far the most frequently donated solid organ in the UK (67.6% of all solid organ donations in 2019/20), followed by liver lobes (which can also be donated by living donors), and heart, lungs and pancreas (which obviously cannot).

How are kidneys from living donors shared in the UK?

Kidneys donated from living donors are ‘shared’ across the UK through the UKLKSS, which includes paired/pooled donations (PPD), and altruistic donor chains (ADCs) that are initiated by non-directed altruistic donors (NDADs).

A person in need of a kidney (the recipient) may have a specific individual (such as a family member, partner or close friend) who is prepared to donate one to them (the donor), but is unable to do so directly since this donor-recipient pair is incompatible by Human Leucocyte Antigen (HLA) type or ABO blood group. Such incompatible linked donor-recipient pairs are registered in the UKLKSS and ‘matched,’ through quarterly Living Donor Kidney Matching Runs (LDKMR), with other incompatible linked donor-recipient pairs that, in some combination, are together compatible for donation exchanges.

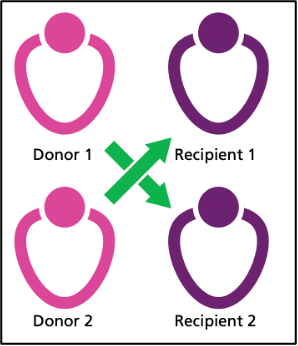

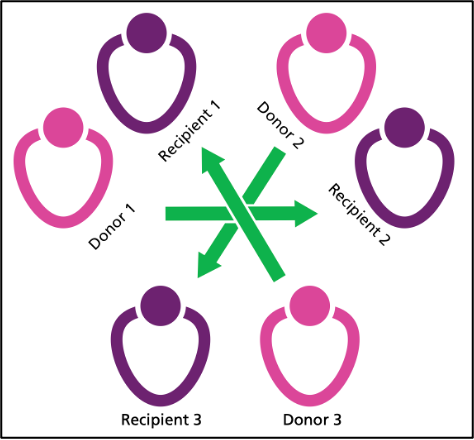

In PPDs, a two-way (in paired donation) exchange occurs between two linked pairs (D1-R1 and D2-R2) in which D1 donates to R2, and D2 donates to R1, while a three- or greater-way (in pooled donation) exchange occurs between more than two linked pairs in which (for example) D1 donates to R2, D2 donates to R3, and D3 donates to R1.

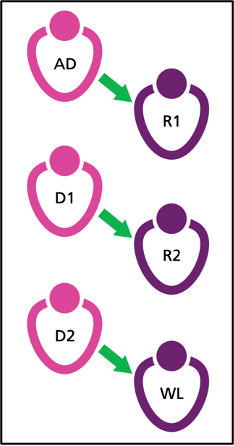

Individuals not in linked pairs but who wish to donate a kidney without the promise of a linked recipient receiving one in return can do so anonymously as NDADs. Such donors are registered into the UKLKSS and donate to a recipient in the paired/pooled scheme, triggering an ADC consisting of multiple donations (NDAD donates to R1, D1 donates to R2, D2 donates to D3, and so on) that culminates (when no compatible linked pairs remain) in the last donor donating to a recipient on the national waiting list. The first non-directed altruistic kidney donation in the UK took place in 2006 and, since the beginning of the UKLKSS in 2012, around 60-100 NDADs have donated a kidney in the UK each year, constituting 6-10% of the total number of annual living donor kidney donations in the country.

Each LDKMR identifies PPD exchanges and ADCs in optimal combinations by considering, amongst other factors: the number of LDKMRs the recipient has previously participated in, the age difference between donors, and the proximity of donors and recipients (the complexity of coordinating ADCs, which may involve three simultaneous donor nephrectomies, cross-country transportation of donated kidneys, and three simultaneous graft insertions, each potentially at different Transplant Centres across the UK, is of substantial scale). Around 250-300 potential recipients partake in each quarterly LDKMR, some 25% of which are usually new patients parking in their first matching run. Since 2012 about 34% of recipients have received a donated kidney after partaking in four or fewer quarterly matching runs (thereby receiving a kidney within one year of entering the UKLKSS), and 15% have done so after partaking in only one matching run.

The process of donating through the UKLKSS

The following summarises the major phases of my donation process through the UKLKSS: pre-LDKMR, post-LDKMR, the surgery, and the recovery.

Pre-LDKMR

- Contacted the Living Donor Co-ordinator Nursing Team in my regional kidney transplant centre (of which there are 23 across the UK) to arrange an initial consultation.

- First appointment with Living Donor Nurse, in which the work-up, surgery, recovery, and associated risks were clearly outlined. I was then left to contact the Team if I wanted to proceed after discussing the process with loved ones (the Team did not chase me for my decision to ensure I felt no undue pressure). When I spontaneously remade contact, a second appointment was arranged.

- Second appointment with Living Donor Nurse, in which I clarified my decision to proceed with the process, and underwent a series of investigations (a renal tract ultrasound scan, ECG, chest X-ray, various fasted blood tests, a series of blood tests following an intravenous infusion [to calculate glomerular filtration rate], and a CT scan of my kidneys).

- Appointment with a renal consultant (for a medical review).

- Appointment with a transplant surgeon (for a surgical review, and to discuss the surgery and recovery in greater detail).

- Appointment with a clinical psychologist (to discuss my general state of mind, and my reasoning for wanting to go ahead with the donation), who also met with a loved one in my absence to gain further insight into my psychological state.

- Appointment with an independent actor from the Human Tissue Authority (to ensure I was not under the influence of any coercive forces and did not stand to gain financially from donating a kidney).

Following these consultations and investigations I was deemed suitable to donate and was entered into the July 2022 LDKMR as a NDAD. I was matched with a potential recipient and would trigger an ADC in which three people with ESRD would receive a donated kidney.

Post-LDKMR

- Surgery date was arranged (this took around four weeks to be agreed upon, as it required coordination between three Transplant Centres across the UK to organise two lots of three simultaneous surgeries [three simultaneous nephrectomies followed by three simultaneous graft insertions] with cross-country transportation of three organs between these surgeries). The surgery date was booked for 10 weeks after the LDKMR.

- Appointment with anaesthetist (to assess anaesthetic risks)

- Appointment with transplant surgeon (to take consent for the surgery)

- Final series of blood tests

- One week prior to the surgery, a member of the ADC caught COVID-19, and the ADC was therefore postponed. It was subsequently rearranged for 7 weeks after the original date and necessitated a further series of blood tests one week prior to the new date.

The surgery

- I was admitted to hospital on the morning of the surgery, had spinal and general anaesthetics, and underwent a laparoscopic left nephrectomy. The surgery took 2.5 hours as planned, encountered no complications, and involved four incisions (three 1cm port sites – at umbilicus, above umbilicus, and below-left of umbilicus – and an 8cm horizontal midline incision in the underwear waistband to retrieve the organ).

- I spent three nights in hospital after the surgery, during which I required decreasing oral analgesia, became increasingly mobile, had the urinary catheter removed, and regained my appetite. I was discharged when I was able to eat, drink, urinate, mobilise and care for myself without assistance, and was provided with a small supply of analgesia, laxatives and blood-thinning injections to take home.

The recovery

- The biggest problems were caused by pain, abdominal swelling, tiredness and constipation. These improved significantly and became much less problematic within the first 5-7 days.

- One week after the surgery (the day of this post) I’m able to slowly walk numerous miles without problems, but continue to follow the advice to avoid driving and heavy lifting for at least the next week. Potential complications, such as wound infections and deep vein thromboses, have thankfully been avoided.

- I receive weekly follow-up phone calls from the Living Donor Nurse, and have direct access to the surgical ward if needed. I’m due to have a follow-up appointment with the surgeon four weeks after the operation. Beyond this, I shall receive routine annual follow-up from the Renal team.

- The appropriate amount of time off work after the operation depends on the nature of one's job. The surgical team could provide a ‘sick note’ (a medical certificate that signals non-fitness for work and initiates sickness payments from the individual's employer) for up to six weeks. I’m a self-employed GP, so am largely desk-based and ineligible for sickness payments, so I hope to return to work two weeks after the operation.

- The UKLKSS allows for reimbursement of basic expenses, such as those spent on travel to and from hospital appointments, if they are requested by the donor.

Some reflections on my experience

ADC and effectiveness

My ADC allowed three donations to take place, while only one would have occurred had I not been matched into an ADC. However, I did not have direct control over this outcome. While the UKLKSS is designed to maximise the number of donations made possible by NDADs, many altruistic donors are matched directly with an individual on the national waiting list who is not in a linked donor-recipient pair, meaning these donors do not form ADCs and their donations only generate single transplantations. NDADs matched in this way have the option to not proceed with their direct donation, and instead wait for the next LDKMR in which they may be matched into an ADC. While this would obviously generate a more effective outcome, denying the original recipient a much-needed kidney presents its own ethical challenges.

Timescale

Due to a series of factors, including the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (which temporarily suspended the UKLKSS), my donation process was substantially delayed multiple times. Absent any postponements, it is likely that the entirety of the process could have been completed within 12-18 months.

No pressure to proceed

I waited for two years after the first appointment before remaking contact with the Team to proceed with the process. During this time the Team made no attempt to contact me, and the decision to initiate contact and proceed with the process was entirely my own and was not subjected to undue pressure from the Team.

I chose to suspend the process when my Mum was diagnosed with a terminal illness. The Team were entirely understanding and supportive of this decision, and allowed me to contact them again once I was ready to continue with the process. Again, I felt no undue pressure from the Team to donate.

Repeated investigations

Due to delays in the process, some of the appointments and investigations exceeded their 'use by dates' and therefore had to be repeated, including that with the renal consultant, and the CT scan, ECG and numerous blood tests.

Identity kept confidential

The identities of all those involved in the ADC – all recipients and donors – were kept confidential throughout the process. Other than the facts that they needed a replacement kidney and live in the UK, I am privy to no details of my kidney's recipient. The recipient has the option to write a letter to be forwarded to me by the Team, in which they can reveal any aspect of their identity if they so wish, but they are under no obligation to do so (I do not have the option to send a letter to the recipient, as per the UKLKSS policy).

Publicity

I chose to publicise my donation to raise public awareness of the potential for individuals to donate a kidney to a stranger. Give A Kidney is the official partner charity for the UKLKSS and assists willing altruistic donors in producing and distributing press releases regarding their donations. I’m awaiting numerous media interviews as a result of this. I also shared my donation on my personal Twitter and Facebook profiles.

Amazing. Well done. I am proud of you!

Thank you so much for sharing your experience, it's really helpful. I have previously wondered what the process looks like in the UK. I am sorry to hear about your mum.

+1. I'm super impressed by people who do this.

This is great! Thanks so much for donating and for writing this guide/reflection!

Thanks for writing this!

Your pre-screening steps look a little different to mine, which could be a regional thing given we were both in the process at around the same time.

Your guide is excellent! (And I have added a link to it from my much more hurried post :))

Very interesting and thank you for posting.

I donated a couple of years ago and although I’m glad I did, I have been plagued with issues since waking up from the operation. I had severe constipation, and very quickly had a very bad infection in the main incision, which took weeks to heal. After care in the hospital was poor, intact it was pretty dire. If wasn’t for my GP, I think I would have been in a very dark place now. The staff at my GPs surgery we’re outstanding.

A couple of months went by that were quite grim at times and then a large Hernia appeared. I got straight on to the hospital, who always told me they‘d fix any problems that may arise, hernia being one of them. That last statement couldn’t be further from the truth. After numerous visits, I was asked if they could sign me off, I said no, not until I was fixed. The second from last consultant I saw initially told me that that it was as good as it gets, and some things go wrong and I’ll have to deal with it. I obviously said no, and that I want a second opinion.

After a while I eventually got to see a hernia specialist that said he could sort, but at best it will be early this year(2023). As of yet, nearly July, I haven’t heard a thing From them. My operation was two years ago now.

From the original consultation it has been a shambles, pre op there were three different surgeons that were going to do the op. Appointments were arranged, and one department not speaking to another, so certain tests seemed unplanned. Follow up calls and general communication was dire.

I am glad I have helped a complete stranger to have a better life by donating, but would I do it again, I don’t really know, and probably wouldn‘t.

Only thing I would say is really check out the hospital that is taking from you, mine was a prestigious NHS hospital that should have done better.

I feel that their interest in me, was only what they could get from me, and not my well-being. Almost as blunt as saying I was a slab of meat to them.

Awesome, thanks for doing this!

Post summary (feel free to suggest edits):

Around 250 people on the UK kidney waiting list die each year. Donating your kidney via the UK Living Kidney Sharing Scheme can potentially kick off altruistic chains of donor-recipient pairs ie. multiple donations. Donor and recipient details are kept confidential.

The process is ~12-18 months and involves consultations, tests, surgery, and for the author 3 days of hospital recovery. In a week since discharge, most problems have cleared up, they can slowly walk several miles, and they encountered no serious complications.

(If you'd like to see more summaries of top EA and LW forum posts, check out the Weekly Summaries series.)