Summary

- This is an investigation into the question of how to reduce the probability of nuclear war effectively.

- After a few words on the context of this research, I present a literature survey that identifies five broad strategies for preventing nuclear war:

- I list the most prominent arguments in favor and in opposition to each strategy, and highlight crucial questions that would need to be answered to rank the strategies in terms of how much promise they hold (more).

- I then describe my failed attempts to assess and rank the strategies, demonstrating why I am skeptical about claims that assert knowledge about the promise each strategy holds (more).

- I end with my conclusions about what should be done to reduce the probability of nuclear war, given a highly uncertain situation where a confident assessment of policy recommendations “based on the evidence” cannot be achieved (more):

- Scholars, researchers and intellectuals should keep investigating the substantive and meta questions raised.

- Policymaking and public discourse should be informed first and foremost by an awareness of the existing uncertainties.

- The most prudent approach for the time is one which diversifies between different approaches for reducing the probability of nuclear war.

Setting the stage

Context for this research project

For a couple of months, I have been engaged in an effort to disentangle the nuclear risk cause area, i.e. to figure out which specific risks it encompasses and to get a sense for what can and should be done about these risks. I took several stabs at the problem, which I will not go into here (see this post instead). One of my attempts consists in collecting a number of crucial questions (cruxes), which I believe need to be answered in order to make an informed decision about how to approach nuclear risk mitigation. Among these crucial questions is the following: What can be done to reduce the probability of nuclear war? In this write-up, I first give a brief account of what the crux in question is and then outline different approaches to answering it. For each approach, I seek to summarize the most prominent proponents and critics and point out crucial questions that account for their disagreements (further cruxes). I then describe my attempts to assess the viability and desirability of each approach, explain why I abandoned that quest, and defend my decision to emphasize the deep empirical uncertainty we face in this space instead of giving tentative policy recommendations to favor one or a few of the proposed approaches.

Terminology

- Abbreviations sometimes used throughout the article

- NWS = nuclear weapons states, i.e. those countries that possess nuclear weapons

- NPT = Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

- Definition of terms whose meaning might be unclear

- I use “preventing”, “helping prevent”, or “reducing the probability of” nuclear war synonymously.

- “Using” nuclear weapons: this is a broad phrase that refers to any purposive action involving nuclear weapons, which includes using the possession of nuclear weapons as a threat and deterrent

- “Detonating” nuclear weapons: this refers to any detonation of nuclear weapons, including accidental ones and those that happen during tests as these weapons are developed; the phrase by itself does not imply that nuclear weapons are used in an act of war and it says nothing about the place and target of the detonation

- “Deploying”/”Employing” nuclear weapons: this is the phrase that refers specifically to the purposive detonation of nuclear weapons against an enemy in war.[1][2]

What is the crux?

In a different post, I make the case for caring about the danger of nuclear war and for working to prevent it[3]. A brief look at political debates as well as the academic literature reveals, however, that it is far from clear what could be done in order to prevent nuclear war. I believe that this question forms one of, possibly the, most consequential cruxes for the traditional[4] nuclear risk field. Below, I try to wrap my head around that controversy, seeking to identify the most prominent proposed strategies for reducing the probability of nuclear war and the specific questions and disagreement surrounding each. I focus explicitly on the probability of any kind of nuclear war and whether there are any promising interventions for reducing it; I do not consider the severity of nuclear conflict and whether there are promising strategies for intervening on that part of what makes up the risk of nuclear war[5].

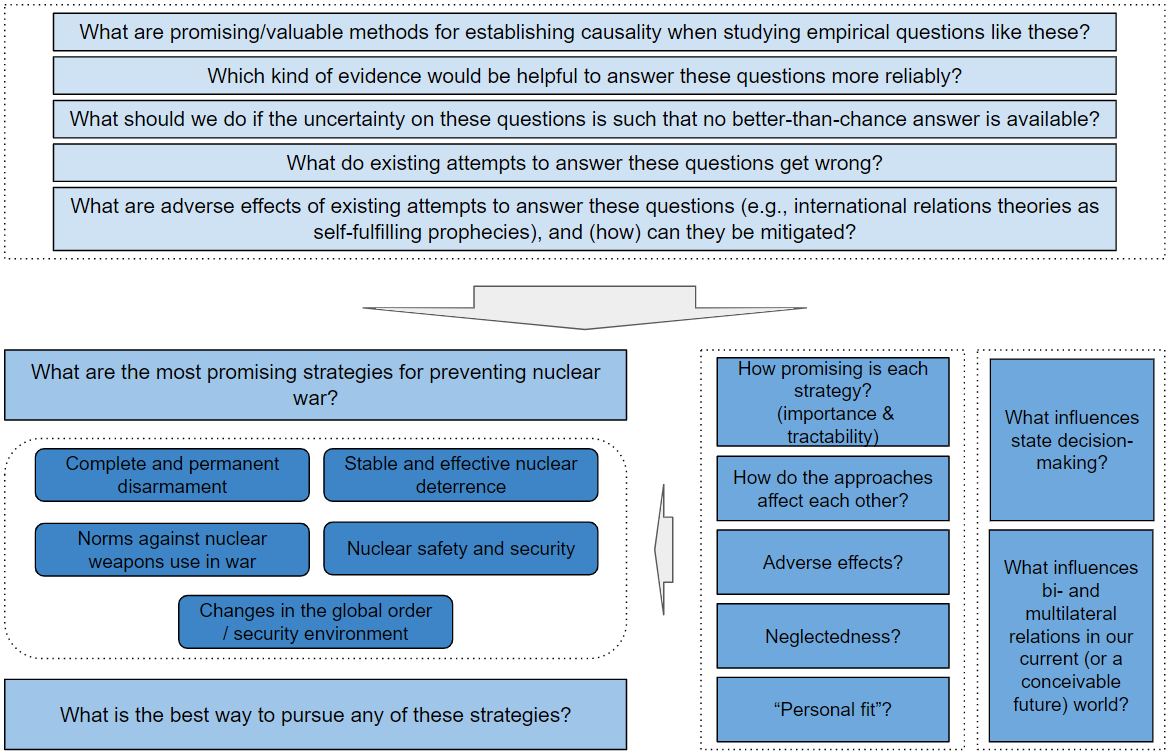

The figure below gives an overview of the meta- and sub-questions that might help figure out how to reduce the probability of nuclear war; it also lists five broad strategies that have been proposed as means to achieving the goal.

Possible strategies for reducing the probability of nuclear war

It seems to me that there are different ways to carve up the debate about how to prevent nuclear war. One such way would be to identify a few concrete, more or less fully developed strategies or theories, promoted either by individual analysts or by groups[6]. While that would give readers (as well as myself) a menu to choose from when devising their own approach, I don’t think it is the best basis for figuring out what actually works when it comes to reducing the probability of nuclear war. This is because these full-fledged strategies unite a number of often implicit assumptions and ideas under one umbrella, which are hard to tease apart and analyze one by one or in conjunction. Furthermore, I fear that it is very easy to miss relevant ideas when picking out a small number of existing approaches to the problem. Another option would be to look at each nuclear-weapons state and figure out what motivates decision-makers in that state to deploy or refrain from deploying nuclear weapons in war. The interest in determinants of “state behavior”, which underlies this option and is relevant for achieving many high-level outcomes, is listed as a basic/foundational question in the overview of cruxes that has resulted from my project; I will thus not go into it here.

A third way to carve up the debate is by trying to come up with a categorization that captures many of the specific proposals for preventing nuclear war. My exploration of the question led me to take this approach, resulting in the following categories:

- Stable and effective deterrence (more)

- Norms against nuclear deployment (more)

- Nuclear safety and security (more)

- Changes to the global order / security environment (more)

- Complete and permanent disarmament (more)

- Meta/Field-building: More research, recruitment of young talent, and accrual of (financial) resources to work towards nuclear war prevention (more here)

These categories won’t be exclusive of each other, as specific proposals for preventing nuclear war are likely to fall into more than one category simultaneously[7], nor fully internally coherent, as there is vigorous debate on what exactly should be done to pursue the goal set by each category. Nevertheless, I hope that the categorization I offer here will be a helpful tool for bringing structure and some clarity to debates on how to reduce the probability of nuclear war.

Stable & effective deterrence

“Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats or limited force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action” (Wikipedia). Nuclear deterrence theory’s basic theorem holds that nuclear weapons states (NWS) deter each other’s deployment of nuclear weapons through the threat of nuclear retaliation.

There are multiple different types of deterrence that people have been and are advocating for: major differences revolve around how many states need to possess weapons for deterrence stability to prevail[8], how large a nuclear arsenal ought to be to constitute a “deterrence capability”[9], and what the importance of factors aside from the weapons stockpiles is[10]. There are thus multiple different deterrence concepts, and - as far as I can tell - all of them are contested. I will not list these different concepts nor recount discussions about pros and cons for each here; determining whether and how nuclear deterrence stability should be pursued requires a more thorough analysis in a separate write-up (in other words: this is a crux of its own)[11].

Regardless of the specific concept at issue, however, there exists a more fundamental debate on nuclear deterrence as a strategy to prevent nuclear war. Some people reject this approach outright, for either or several of the following beliefs: 1) nuclear deterrence is not actually what prevents decision-makers from launching nuclear attacks, which is why the strategy is worthless (and dangerous, in as far as it engenders a false sense of security and discourages other approaches to nuclear risk reduction)[12]; 2) nuclear deterrence is fundamentally immoral[13]; and 3) given an irreducible risk of nuclear accidents as well as incomplete rationality on the side of decision-makers in NWS, nuclear deterrence is insufficient to prevent nuclear war[14]. All of these claims are contested and an assessment of deterrence as a promising strategy would require some resolution or justified stance on these controversies (further cruxes), which I am not capable of producing with any level of seriousness/confidence (without having done a thorough primary-source investigation):

- (How) Does nuclear deterrence prevent decision-makers from launching nuclear attacks?

- How (un-)reliable is nuclear deterrence, especially given human fallibility, and how reliable can it be expected to be over the coming decades?

- How likely is an accident involving nuclear weapons facilities in any given year, and how is that going to change over the next few decades? Are there viable interventions to significantly decrease the likelihood of an accident?

- How is the (im-)morality of nuclear deterrence to be assessed?

Norms against nuclear deployment (in its strongest form, the nuclear taboo)

Some scholars, especially those of a constructivist bent, have argued that nuclear war is being and has been averted at least in part by norms that discourage leaders of NWS from making (or from seriously contemplating) the decision to deploy nuclear weapons against “enemy” targets . The claim is either that decision-makers feel normative pressure from domestic and/or global public opinion, or that they have internalized these norms themselves, or both.

Whether norms have any significant effect on how nuclear weapons are used is contested. There is debate on the power and effect of norms on (global) politics in general[15]. In the nuclear space more specifically, discussions have centered mostly on the so-called nuclear taboo: “The “nuclear taboo” refers to a powerful de facto prohibition against the first use of nuclear weapons. The taboo is not the behavior (of non-use) itself but rather the normative belief about the behavior” (Tannenwald 2007, p. 10). While some authors have debated the existence and strength of the nuclear taboo on a general level[16], others decided to break it down into the two major pathways by which norms could affect the decision to (not) deploy nuclear weapons and have argued over the likelihood of those[17]. Here are the two pathways and the crucial questions to determine to what extent each is active in preventing nuclear war:

- Pathway #1: external normative pressure

- Is there a strong popular norm against deploying nuclear weapons?

- What is the effect of public opinion on decision-making in NWS?

- Pathway #2: internal normative motivation

- Is there a strong norm/aversion against deploying nuclear weapons amongst decision-making elites in NWS?

- What is the effect of personal beliefs, convictions, and intuitions of elite politicians on their decision-making?

Arguably, there are a number of norms aside from the nuclear taboo which could have an effect on whether or not nuclear weapons are deployed: norms about bi- and multilateral relations, about appropriate behavior in conflict and war, and about the role of different institutions for resolving tensions. I am not aware of much literature specifically on these norms and their role in preventing nuclear war, though the volume of publications in this field is rather large and I did not spend much time looking for relevant resources.

In addition to the above, there is also controversy over how norms on nuclear weapons interact with the other possible strategies to reducing the probability of nuclear war. It seems plausible that these interactions exist and are important, chiefly because norms affect how state officials make their decisions. However, the precise nature of these interactions is not entirely straightforward, both in terms of their direction (do norms increase or decrease the chance that other approaches, such as deterrence or disarmament, succeed?) and their strength (how much do these norms affect the success probabilities of other approaches?).

As done in the other subsections, I don’t try to resolve these debates and instead note the sub-questions as relevant cruxes that are in need of deeper study (or that cannot be answered well given the available evidence, thus making a confident assessment of the value of this approach difficult).

Nuclear safety & security

In this write-up, I take nuclear safety to mean that there are no accidental detonations of nuclear weapons nor any technical or human errors that lead to the inadvertent deployment of nuclear weapons against “enemy targets”[18]. An example for a technical error would be an incident in 1983, where Soviet “satellites mistook sunlight reflecting off the tops of clouds for missile launches” (USC 2015), falsely alerting Soviet Lieutenant Stanislov Petrov of an incoming US nuclear attack, which could plausibly have led to nuclear war had the lieutenant in question decided to retaliate instead of waiting for confirmation. The various types of human errors that could increase the probability of nuclear conflict are well outlined in an early Bulletin article by Lloyd Dumas (1980): issues of drug abuse and mental illness, erratic or careless behavior due to relative isolation, stress (in some situations) and monotony (in other situations), coordination problems (especially as regards the transmission of information between upper-level and lower-level employees), biases in group decision-making, and the need to react quickly in times of crisis all make an accidental detonation or inadvertent deployment of nuclear weapons more likely. A list of actual accidents and close calls (Conn 2016) reinforces the sense that human fallibility poses a serious danger of nuclear weapons being deployed without full intention at some point in the future. Efforts to improve nuclear safety include technical innovations, but they also encompass policy advocacy, most prominently calls for taking nuclear missiles off hair-trigger alert, such that accidental warnings and similar incidents are less likely to result in nuclear escalation[19].

By nuclear security, on the other hand, I refer to the prevention of or protection against the theft of nuclear weapons and weapon-relevant material, as well as attacks (physical or cyber) on nuclear weapons systems and facilities by “rogue actors”[20]. Most efforts to combat the threat of nuclear terrorism, to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons to North Korea and Iran, and to guard against cyber attacks fall into this category.

I believe that attempts to increase the safety and security of nuclear weapons and weapons systems is one of the least controversial approaches to reducing the probability of nuclear war. It is criticized mainly for being too moderate, distracting from more radical and more promising approaches. The harshest version of this criticism takes the form of accusations against NWS for being disingenuous and hypocritical in their emphasis on the importance of nuclear security (and, to a lesser extent, safety), while refusing to acknowledge that their insistence on retaining a nuclear weapons arsenal is the larger danger and root cause of the risk[21].

Without going too much into depth on this approach and the debate surrounding it[22], I think the questions needed for assessing its value are relatively straightforward:

- How likely is a nuclear accident to lead to nuclear war? / What are risks to nuclear safety?

- How large is the probability of a nuclear accident?

- What, if anything, can be done to reduce the probability of nuclear accidents?

- What, and how large, are risks to nuclear security?

- How likely are “bad actors” to engage in attacks on nuclear weapons facilities or to try to steal nuclear materials?

- How likely are these efforts by “bad actors” to succeed?

- What can be done to mitigate those risks to nuclear security?

Security environment (of nuclear-weapons states)

The idea that changes in the international/global security environment constitute the most promising path to preventing nuclear war is as old as nuclear weapons themselves[23]. Discussions throughout the last century have featured unresolved controversies over what kind of changes are desirable (helpful for reducing or eliminating the probability of nuclear war) and over how to pursue those changes. In addition, the literature features competing accounts of how changes to the security environment interact with the other approaches I list here.

On the last point, some commentators view a changed security environment as a long-term goal and one or several of the other approaches (disarmament, deterrence stability, strengthening norms, ensuring nuclear safety and security) as either a means for getting there or as a short-term fix to survive the interim until desirable changes in the security environment have been achieved. For instance, some nuclear abolitionists argue that “the commitment to the elimination of nuclear weapons, and the process of elimination, also create enormous opportunities to reach a stable and more cooperative international system” (Payne 1998, p. 11) by reducing tensions, hostility, and global injustice. Others, however, emphasize the reverse effect, i.e. the positive impact that changes in the security environment can have on disarmament progress, deterrence stability, the strengthening of favorable norms, and nuclear security. Because of that, some commentators have argued that reforming the global order should be the overarching concern, labeling alternative approaches to preventing nuclear war as unfeasible and/or insufficient, and relegating them to the sidelines[24].

As regards the question of what kinds of change are needed to improve the global security environment, perspectives differ widely. On the moderate side stand proposals for reducing and managing inter-state tensions, especially between “great powers”, through means such as confidence-building measures, the establishment of permanent communications channels, security guarantees, and certain declaratory policies[25]. Radicals, on the other hand, call for a fundamental reform (or revolution) of the way global politics is done; ideas in this bucket range from the institution of a world government[26] to the rejection of states as the central actors in global affairs and of power politics as the core conceptual framework used for thinking about global challenges (of which the risk from nuclear weapons is one)[27]. Somewhere in-between these two extremes lie proposals that call for more institutionalized coordination between states (and non-state actors)[28], a deepening (or loosening) of inter-state interdependencies (economic and otherwise)[29], a reduction in inequalities between countries[30], or for some intervention to affect the “polarity” (distribution of power across states) in the international system[31].

An attempt to study this topic rigorously can quickly branch out into a myriad of sub-problems: For each proposal to reform the security environment, questions can be raised as to its feasibility, its desirability, and the best ways to achieve it; and these questions can be further broken down, similar to how I successively broke down the question of how to help prevent nuclear war in this essay. As before, I explicitly opt against a more in-depth analysis of the approach, being content with having outlined the various different manifestations this approach can take in practice and with having identified sub-questions that merit more sophisticated study.

Complete and permanent nuclear disarmament

On paper, complete and permanent disarmament is endorsed as the eventual goal by a widespread constituency: it is enshrined in the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which was signed by 191 states, including some (US, Russia, China, UK, France) but not all (India, Pakistan, Israel) states currently in possession of nuclear weapons; it is supported by the United Nations[32]; it is championed by many civil society organizations and individuals that take a stance on nuclear issues[33]; and it has found considerable academic support across the last seventy years[34]. However, there is quite some variation on what kind of disarmament different supporters call for[35], what they consider the appropriate path towards a nuclear weapons free world[36], and arguably how serious their calls for eventual disarmament are (skepticism has been particularly high with regards to the proclamations of the NWS).

Given this diverse constituency, the arguments brought into play in favor of complete and permanent disarmament are quite varied. One strand of reasoning holds that the credible prospect of global nuclear disarmament is needed to avert a world of widespread nuclear proliferation (acquisition and build-up of nuclear weapons arsenals by numerous states). The current nuclear order consisting of some states with and many without atomic weapons is unsustainable, according to this argument, because non-NWS are unlikely to continuously put up with the inherent inequality in that regime[37] and will sooner or later take steps to acquire their own arsenals. Add to this the claim that widespread proliferation leads to a higher chance of nuclear accidents as well as of deterrence failure[38], thus increasing the likelihood of nuclear war, and you get a logically coherent justification for nuclear disarmament.

The strength of this first argument depends on answers to the following questions (further cruxes), which I cannot provide with a great level of confidence at this point:

- (How much) Do missing steps towards nuclear disarmament, and a failure of NWS to disarm over the mid- to long-term, encourage other states or non-state actors to obtain nuclear weapons arsenals of their own (horizontal proliferation)?

- (How much) Does horizontal nuclear proliferation increase the probability of nuclear war?

A second line of reasoning holds that barring eventual complete and permanent disarmament, the risk of nuclear weapons deployment is too high, even if there is no further acquisition of nuclear weapons by states that don’t currently possess them. This is based on the premise that deterrence does not reliably prevent nuclear war and/or that there is a significant chance of a nuclear accident in any given year[39], which adds up to the conclusion that nuclear war grows more likely the longer nuclear weapons exist (compounding probability across time) and becomes close-to-inevitable eventually[40]. For instance, if the probability of nuclear war due to an accident or due to deterrence failure is around 1.17% per year (a number suggested by an analysis by Rodriguez 2019), it adds up to a 60% chance of nuclear war sometime within one person’s lifetime (assuming 75 years of life expectancy: 1-(1-.0117)^75; calculation taken from Tabarrok 2022).

Once again, acceptance of this justification for disarmament hinges on answers to a few empirical questions:

- How (un-)reliable is nuclear deterrence, especially given human fallibility, and how reliable can it be expected to be over the coming decades?

- How likely is an accident involving nuclear weapons facilities in any given year, and how is that going to change over the next few decades? Are there viable interventions to significantly decrease the likelihood of an accident?

- How likely are changes in the world that will make concerns about deterrence failure and accidents obsolete within the near- to mid-future (such that compounding probabilities are less of an issue)?

Some proponents of nuclear disarmament take a somewhat different approach to the whole issue, focusing less on the reasons why nuclear weapons deployment is more likely than often assumed and instead arguing that disarmament is a moral and legal duty for NWS. The immortality of the weapons is grounded in the catastrophic effects that they would have if deployed in war, in the oppressive and destabilizing effects they already have on the global order, and in the financial and health costs of their production and maintenance[41]. In addition, critics have argued that the idea of nuclear deterrence as a purposive strategy is problematic from a moral and international law perspective, because it is built on “a conditional commitment to a direct attack on millions of noncombatants, a commitment often interpreted by deontologists as a commitment to mass murder” (Lackey 1985, p. 156).

In addition to these arguments for the need of nuclear disarmament, proponents of this approach also necessarily endorse the following two claims: (1) it is technologically feasible to have a global mechanism for verifiably getting rid of all nuclear weapons and for monitoring that no new ones are being built; and (2) it is politically feasible, or at least can become so at some point, to get rid of all nuclear weapons. As with all the preceding arguments, these questions are contested and no obvious resolutions seem discernable from the literature.

In summary, then, I have encountered the following set of arguments in favor of pursuing complete and permanent nuclear disarmament as a promising strategy to reduce the probability of nuclear war:

- Lack of nuclear disarmament encourages the acquisition and buildup of weapons arsenal by ever more states (proliferation), which in turn increases the probability of nuclear war.

- As long as nuclear weapons exist, there is a significant chance of nuclear war because deterrence is no guarantor for non-deployment and because nuclear weapons may be set off by accident.

- Nuclear disarmament is a moral and legal imperative.

- Complete and permanent nuclear disarmament is both politically and technologically feasible.

Support for any of these arguments, and for the different approaches to reduce the probability of nuclear war more generally, hinges on a number of empirical and normative questions (further cruxes). My review of the literature did not reveal any widely-accepted and/or empirically well-supported answers to these questions, which makes me hesitant to conclude anything here. It would strike me as irresponsible and somewhat pointless to cite and compare available pieces of evidence and to draw conclusions based on my cursory look at the topic; instead, I think these questions deserve more scrutiny than I can provide without doing a thoroughgoing primary investigation (to determine whether we have sufficient evidence/reason to give an answer at all and, if so, to identify that answer). I will thus leave them unaddressed - and leave myself and the reader without a strong basis for evaluating the strength of the arguments at issue. I give a more in-depth justification of this choice to refuse an assessment in the last section of this post.

Relevant questions to figure out how to prevent nuclear war

I would argue that the main value of my investigation of this broad question has been to generate sub-questions, breaking up the complex problem of how to prevent nuclear war into more manageable pieces and helping participants in the debate nail down more precisely what it is they disagree about. The result of this work is the following list of further cruxes, building off the categories of approaches to preventing nuclear war that I identified and described above:

- How promising is each approach?

- Permanent and complete nuclear disarmament

- Is permanent and complete nuclear disarmament feasible?

- How desirable is permanent and complete nuclear disarmament?

- (How much) Do missing steps towards nuclear disarmament, and a failure of NWS to disarm over the mid- to long-term, encourage other states or non-state actors to obtain nuclear weapons arsenals of their own (horizontal proliferation)?

- (How much) Does horizontal nuclear proliferation increase the probability of nuclear war?

- How likely is an accident involving nuclear weapons facilities in any given year, and how is that going to change over the next few decades? Are there viable interventions to significantly decrease the likelihood of an accident?

- How likely are changes in the world that will make concerns about deterrence failure and accidents obsolete within the near- to mid-future (such that compounding probabilities are less of an issue)?

- What is the best strategy for achieving complete and permanent disarmament?

- Security environment

- What kind of security environment makes nuclear war less likely?

- What can be done to bring that security environment about?

- Norms against the deployment of nuclear weapons in war

- How strong is the effect of norms against nuclear weapons deployment?

- Is there a strong norm against deploying nuclear weapons in the general population, and what is the effect of public opinion on decision-making in NWS?

- Is there a strong norm/aversion against deploying nuclear weapons amongst decision-making elites in NWS, and what is the effect of personal beliefs, convictions, and intuitions of elite politicians on their decision-making?

- Which norms other than the nuclear taboo have a plausible impact on decisions to (not) deploy nuclear weapons in war?

- What can be done to effectively promote/strengthen norms?

- What are developments or factors that weaken norms against nuclear weapons deployment, and is there something we can do to counteract them?

- How strong is the effect of norms against nuclear weapons deployment?

- Nuclear deterrence

- (How) Does nuclear deterrence prevent decision-makers from launching nuclear attacks?

- How (un-)reliable is nuclear deterrence, especially given human fallibility, and how reliable can it be expected to be over the coming decades?

- How likely is an accident involving nuclear weapons facilities in any given year, and how is that going to change over the next few decades? Are there viable interventions to significantly decrease the likelihood of an accident? (More below)

- How is the (im-)morality of nuclear deterrence to be assessed?

- What can be done to stabilize deterrence?

- Nuclear safety

- How likely is a nuclear accident to lead to nuclear war? / What are risks to nuclear safety?

- How large is the probability of a nuclear accident?

- What, if anything, can be done to reduce the probability of nuclear accidents?

- Nuclear security

- What are risks to nuclear security? (theft of nuclear materials, attacks against weapons systems)

- What can be done to mitigate those risks to nuclear security?

- Permanent and complete nuclear disarmament

- How do these approaches affect each other?

- (How much) do reductions in the probability of nuclear war - brought about by heightened levels of nuclear safety and security, by strengthened norms against nuclear deployment, and/or by a more secure environment for and better relations between NWS - alleviate the pressure to disarm? [moral hazard]

- (How much) do advancements towards one or some of these goals create momentum for achieving one of the others (e.g., a better security environment leading to more support for disarmament steps)?

- Are nuclear deterrence and the nuclear taboo incompatible, and does focus on / belief in one weaken the other?

- …

- What is the best that each of these approaches could achieve / How much could each of these approaches reduce the probability of nuclear war in the best of circumstances, and what are additional benefits that each approach may bring?

- What are conceivable downsides of pursuing each of the approaches, and how bad would they be?

Assessing strategies for reducing the probability of nuclear war

As mentioned repeatedly in the description of each strategy, I am skeptical about claims that assert knowledge about how promising (important and tractable) each approach is, and also about supposedly valid/confident answers to any of the more fine-grained questions I pose above (e.g., How likely is an accident involving nuclear weapons facilities in any given year, and how is that going to change over the next few decades?). In this section, I will shortly describe my attempts to reduce my skepticism and to come to an informed assessment of different strategies for reducing the probability of nuclear war. I explain my dissatisfaction with each of these strategies, and outline my conclusions for what to do in the face of deep uncertainty: In short, I argue that this is a situation where an empirically grounded assessment of policy recommendations does more harm than good; that scholars, researchers and intellectuals should keep investigating the substantive [42]and meta[43] questions raised; that policymaking and public discourse should be informed first and foremost by an awareness of the existing uncertainties; and that the most prudent approach for the time being seems to me to be one which diversifies between different strategies for reducing the probability of nuclear war.

My attempts to rank the strategies

Okay, let’s start with a short recap of how I went about the assessment task: A first thing to note is that I was unsure about the value of this enterprise from the very start of the fellowship, suspecting that the main value of my research project would be in clarifying relevant questions and outlining possible perspectives on these questions, not in actually resolving the questions and settling on one of the perspectives. This means that I came to the task with a bias towards skepticism, and the fact that my conclusions after ten weeks of working on the topic continue to embody that bias may invite some suspicions about the validity of my reasoning processes[44]. My decision for attempting an assessment in spite of my doubts was prompted by conversations I had with my mentor, with the CERI nuclear risk research coordinator, and with other fellows in the program, which alerted me to the merits of formulating concrete policy recommendations if possible and unsettled my conviction that “merely” highlighting uncertainties and debunking unduly confident beliefs is one of the most valuable things social scientists (can) do.

I considered a few approaches for assessing the different strategies identified, and took a stab at some of them:

- Red-Teaming: My description of each strategy, and especially the identification of crucial questions to determine the promise of each, embodies some of the elements of a Red-Teaming approach. I didn’t pursue this in more detail because of (a) the sense that the strategies are too vague and varied to allow for an in-depth critique using Red-Teaming techniques (individual proposals to reduce the probability of nuclear war, such as the specific nuclear doctrine of government X or an action plan submitted by the United Nations at a given point in time, would seem more suited for that); and (b) time constraints (Red-Teaming each strategy would have required substantial time commitments from my side, which I didn’t have or preferred to spend on other tasks).

- Learning by Writing: After I had come up with the categorization of strategies, I briefly resolved to explore my views on how to prioritize between them through a Learning by Writing exercise as outlined by Holden Karnofsky in this blog post (2022). I failed to force myself to settle on a first hypothesis that would single out one of the strategies as the most promising one. Instead, the hours spent on the Learning by Writing exercise devolved into an exploration of the epistemological and moral challenge of dealing with deep uncertainty, resulting in me spending substantial time reading, thinking, and talking about different responses to that challenge. I think that I learned a great deal from that experience, I am still grappling with the challenge and will probably continue to for the foreseeable future, and am kind of glad to have stumbled down that rabbit hole; however, the “bad news” of all that is that I basically aborted the Learning by Writing exercise, failing to follow through on the steps outlined by Karnofsky and ending up without a well-informed hypothesis for how best to help prevent nuclear war.

- Hits-based approach: Another approach I took consists in an analysis of the possible upsides and downsides of each strategy. The idea was that this analysis could unearth some strategies with high potential upsides and low conceivable downsides (or the reverse), which would help filter out promising interventions even when their success probabilities are highly uncertain and/or estimated to be low. However, it turned out that the strategies are all marked by potentially high upsides and downsides, such that the hits-based analysis did not seem to justify recommending any one of them over the others.

- Assigning values and probabilities based on my subjective credences (like a good Bayesian?): I considered constructing some model for estimating the promise of each strategy (consisting of the questions I identified as relevant, of the importance-tractability-neglectedness criteria, or of some other set of variables), and populating that model with my best guesses at appropriate probabilities and values. These guesses wouldn’t be completely unfounded, since I did spend some substantial time studying the topic and have seen many bits of seemingly relevant evidence and reasonable arguments, and they could be made more robust through sensitivity analyses. In spite of that, I felt like an utter fraud and like an irresponsible researcher/scholar/intellectual when sitting down to actually come up with those numbers. I did not put down any numbers and aborted the attempt.

My reasons for refusing to rank the strategies

I recognize that my abandonment of the Learning by Writing exercise and of the expected values estimation (based on parameters provided by my subjective credences) is not neatly justified by the account given above. In this section, I try to spell out my reasons for refusing to take a stance and for preferring to highlight and emphasize the extent of our uncertainty instead.

I believe that researchers can cause significant negative consequences when they support actions in spite of being highly uncertain about those actions’ effects:

- A research report that suggests answers can create a false sense of certainty and thus reduce the perceived need for cautious action, further research, and/or alternative decision-making procedures.

- Research, especially when heavily reliant on intuitions and plausibility judgements, may be systematically biased and may in turn contribute to reinforcing biased and flawed narratives (because research has effects on what is considered/perceived as common-sensical, intuitive, and natural).

- Expert advice is a valuable good in democratic societies, and trust and reliance on expert advice (among elites but especially among the wider public) may be harmed if researchers fail to communicate the level of confidence their findings/guesses ought to inspire.

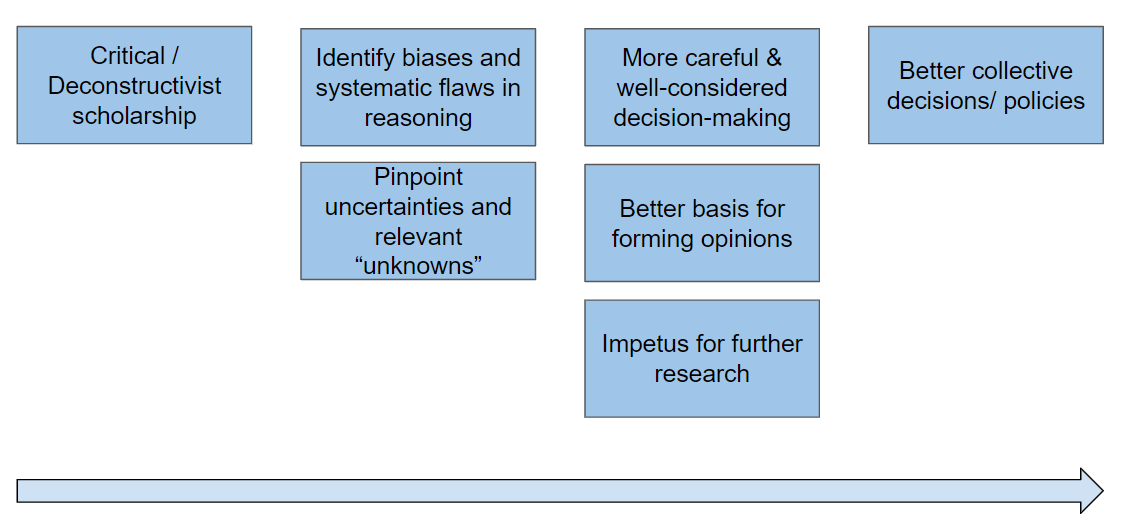

Inspired by these concerns, I would argue that there is substantial value in epistemically modest and skeptical scholarship that draws attention to the range of alternative answers to a given question and to the uncertainty we face when forced to decide between these answers. Such scholarship can disrupt the proliferation of bias, discover systematic flaws and distortions in our understanding of social phenomena, and unsettle (over-)confidence. That can push decision-makers to be more critical of their own and of others’ plans for action. In addition, it can facilitate people’s ability to develop an informed opinion on tricky questions. This carries the potential to enrich debates on these tricky questions and to improve a society’s ability to respond “wisely” to uncertain situations.

In short, I believe in the value of critical scholarship that emphasizes uncertainty and deconstructs epistemically shaky knowledge claims; I think that it is that belief which caused me to rebel against rank-ordering the different strategies to prevent nuclear war in this research project, and to insist on the lack of a sufficiently strong evidential or theoretical basis to underpin such a ranking.

My alternative recommendation: More research, and a diversification in strategies

Given the above, I conclude by recommending a multi-pronged approach to reducing the probability of nuclear war. This means that I would caution against elevating one of the goals to be the sole priority, and against discouraging people and organizations from pursuing any one of them. Instead, I think that efforts on each goal should continue at least in some capacity, and that further research is sorely needed, especially regarding how the different goals affect each other (e.g., do attempts to stabilize deterrence weaken or strengthen norms against nuclear weapons deployment?), whether there are strong reasons against pursuing any one of the goals (e.g., because there is good reason to believe that it may actually increase the probability of nuclear war, or because there is good reason to believe that it is unattainable), and how each goal can be pursued most effectively (e.g., what is a promising path towards disarmament and which steps/interventions advance that path?). On top of that, I advocate for critical research that is primarily aimed at spotting weaknesses and biases in prominent arguments and policy recommendations in the field.

Other pieces I wrote on this topic

- Disentanglement of nuclear security cause area_2022_Weiler: written prior to CERI, as part of a part-time and remote research fellowship in spring 2022)

- Cruxes for nuclear risk reduction efforts: A proposal

- A case against focusing on tail-end nuclear war risks

- List of useful resources for learning about nuclear risk reduction efforts: This is a work-in-progress; if I ever manage to compile a decent list of resources, I will insert a link here.

- How to decide and act in the face of deep uncertainty?: This is a work-in-progress; if I ever manage to bring my thoughts on this thorny question into a coherent write-up, I will insert a link here.

References

Atkinson, Carol. 2010. “Using nuclear weapons.” Review of International Studies, 36(4), 839-851. doi:10.1017/S0260210510001312

Ban, Ki-Moon. 2008. “The United Nations and Security in a Nuclear Weapons-Free World.” A speech delivered by the Secretary-General to the East-West Institute, published on the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation’s website, October 24. https://www.wagingpeace.org/the-united-nations-and-security-in-a-nuclear-weapons-free-world/.

Brito, Dagobert L., and Michael D. Intriligator. 1996. “Proliferation and the Probability of War: A Cardinality Theorem.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 40 (1): 206–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002796040001009.

Buzzard, Anthony W. 1956. “Massive Retaliation and Graduated Deterrence.” World Politics 8 (2): 228–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/2008972.

Cashman, Greg. 2013. What Causes War?: An Introduction to Theories of International Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Clare, Stephen. 2021. “Great Power Conflict.” Founders Pledge. https://founderspledge.com/stories/great-power-conflict.

Conn, Ariel. 2016. “Accidental Nuclear War: a Timeline of Close Calls.” Future of Life Institute, February 23. https://futureoflife.org/resource/nuclear-close-calls-a-timeline/.

Craig, Campbell. 2020. “Can the Danger of Nuclear War Be Eliminated by Disarmament?” In Non-Nuclear Peace: Beyond the Nuclear Ban Treaty, edited by Tom Sauer, Jorg Kustermans, and Barbara Segaert, 167–80. Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26688-2_9.

Davis Gibbons, Rebecca, and Keir Lieber. 2019. “How Durable Is the Nuclear Weapons Taboo?” Journal of Strategic Studies 42 (1): 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2018.1529568.

Dumas, Lloyd J. 1980. “Human Fallibility and Weapons.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 36 (9): 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1980.11458778.

EA Forum. n.d. “Red teaming.” In Effective Altruism Forum. Centre for Effective Altruism. Accessed November 13, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/red-teaming.

Falk, Richard. 2017. “Challenging Nuclearism: The Nuclear Ban Treaty Assessed.” Foreign Policy Journal, July. https://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2017/07/14/challenging-nuclearism-the-nuclear-ban-treaty-assessed/.

Fisher, Roger. 1981. “Preventing Nuclear War.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 37 (3): 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1981.11458828.

Forsyth, James Wood, B. Chance Saltzman, and Gary Schaub. 2010. “Minimum Deterrence and Its Critics.” Strategic Studies Quarterly 4 (4): 3–12.

Gienapp, Anne, Alex Chew, Adele Harmer, Alex Ozkan, Chan, and Joy Drucker. 2020. “Nuclear Challenges Big Bet: 2020 Evaluation Report.” evaluation report commissioned by the MacArthur Foundation and written by ORS Impact. https://www.macfound.org/press/evaluation/nuclear-challenges-big-bet-2020-evaluation-report.

ICAN, (International Campaign to Ban Nuclear Weapons). n.d. “Why a Ban?” Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.icanw.org/why_a_ban.

Ikle, Fred Charles. 1972. “Can Nuclear Deterrence Last out the Century.” Foreign Affairs 51 (2): 267–85.

Iqbal, Saghir. 2018. Nuclear Apartheid: Bullying, Hypocrisy and the Double Standards on Nuclear Weapons.

Karnofsky, Holden. 2022. “Learning By Writing.” Cold Takes (blog). February 22, 2022. https://www.cold-takes.com/learning-by-writing/.

Kelleher, Catherine M., and Judith Reppy, eds. 2011. Getting to Zero: The Path to Nuclear Disarmament. Stanford University Press.

Lackey, Douglas P. 1985. “Immoral Risks: A Deontological Critique of Nuclear Deterrence.” Social Philosophy and Policy 3 (1): 154–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265052500000212.

Lavoy, Peter R. 1995. “The Strategic Consequences of Nuclear Proliferation: A Review Essay.” Security Studies 4 (4): 695–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636419509347601.

Legro, Jeffrey W. 1997. “Which Norms Matter? Revisiting the ‘Failure’ of Internationalism.” International Organization 51 (1): 31–63. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081897550294.

LessWrong. n.d. “Double-Crux.” In LessWrong. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.lesswrong.com/tag/double-crux.

Leveringhaus, Nicola, and Andrew Hurrell. 2017. “Great Power Accommodation, Nuclear Weapons and Concerts of Power.” In Great Power Multilateralism and the Prevention of War. Routledge.

Lipson, Michael. 2005. “Organized Hypocrisy and the NPT.” https://www.academia.edu/6248425/Organized_Hypocrisy_and_the_NPT.

Lodgaard, Sverre. 2009. “Toward a Nuclear-Weapons-Free World.” Daedalus 138 (4): 140–52. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed.2009.138.4.140.

Lupovici, Amir. 2010. “The Emerging Fourth Wave of Deterrence Theory—Toward a New Research Agenda.” International Studies Quarterly 54 (3): 705–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00606.x.

Masters, Dexter, and Katherine Way, eds. 1946. One World or None. New York: Whittlesey House.

Mathur, Ritu. 2016. “Sly Civility and the Paradox of Equality/Inequality in the Nuclear Order: A Post-Colonial Critique.” Critical Studies on Security 4 (1): 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2015.1106428.

McDonough, David S. 2006. Nuclear Superiority: The “new Triad” and the Evolution of Nuclear Strategy. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203717462.

McNamara, Robert S., and Hans A. Bethe. 1986. “Reducing the Risk of Nuclear War.” Bulletin of Peace Proposals 17 (2): 121–30.

Noel-Baker, Philip. 1958. The Arms Race: A Programme for World Disarmament. Oceana Publications.

Payne, Keith B. 1998. “The Case against Nuclear Abolition and for Nuclear Deterrence.” Comparative Strategy 17 (1): 3–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495939808403130.

Perkins, Raymond K. 1985. “Deterrence Is Immoral.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 41 (2): 32–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1985.11455910.

PSFG, (Peace and Security Funders Group). n.d. “Peace and Security Funders Group.” Homepage. Peace and Security Funders Group. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.peaceandsecurity.org.

———. n.d. “Peace and Security Funding Map.” Database (Foundation Maps by Candid). Accessed October 9, 2022. https://maps.foundationcenter.org/#/list/?subjects=SS1060&popgroups=all&years=all&location=6295630&excludeLocation=0&geoScale=ADM0&layer=recip&boundingBox=-139.219,-31.354,135,66.513&gmOrgs=all&recipOrgs=all&tags=all&keywords=&pathwaysOrg=&pathwaysType=&acct=psfg&typesOfSupport=all&transactionTypes=all&amtRanges=all&minGrantAmt=0&maxGrantAmt=0&gmTypes=all&minAssetsAmt=0&maxAssetsAmt=0&minGivingAmt=0&maxGivingAmt=0&andOr=0&includeGov=0&custom=all&customArea=all&indicator=&dataSource=oecd&chartType=trends&multiSubject=1&listType=recip&windRoseAnd=undefined&zoom=2.

Quackenbush, Stephen L. 2010. “Deterrence theory: where do we stand?” Review of International Studies, 37(2): 741-762. doi:10.1017/S0260210510000896.

RAND. n.d. “Nuclear Deterrence”, https://www.rand.org/topics/nuclear-deterrence.html.

Rauchhaus, Robert. 2009. “Evaluating the Nuclear Peace Hypothesis: A Quantitative Approach.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (2): 258–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002708330387.

Rodriguez, Luisa (Luisa_Rodriguez). 2019. “How Likely Is a Nuclear Exchange between the US and Russia? - EA Forum.” EA Forum (blog). June 20, 2019. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/PAYa6on5gJKwAywrF/how-likely-is-a-nuclear-exchange-between-the-us-and-russia.

Rohlfing, Joan. 2021. “Remarks by Joan Rohlfing at Effective Altruism Global: London 2021.” Effective Altruism Global Talk, London, October 30. https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/remarks-by-joan-rohlfing-at-effective-altruism-global-london-2021/.

Roser, Max. 2022. “Nuclear Weapons: Why Reducing the Risk of Nuclear War Should Be a Key Concern of Our Generation.” Our World in Data (blog). March 3, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/nuclear-weapons-risk.

Russell, Bertrand. 1959. Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare. New York, Simon and Schuster. http://archive.org/details/commonsensenucle00russ.

Rydell, Randy. 2018. “A Strategic Plan for Nuclear Disarmament: Engineering a Perfect Political Storm.” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament 1 (1): 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2017.1410386.

Sagan, Scott, and Kenneth N. Waltz. 1995. The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: A Debate. W. W. Norton & Co. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/1995-05-01/spread-nuclear-weapons-debate.

Sauer, Tom, Jorg Kustermans, and Barbara Segaert, eds. 2020. Non-Nuclear Peace: Beyond the Nuclear Ban Treaty. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26688-2.

Shultz, George P., William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger, and Sam Nunn. 2007. “A World Free of Nuclear Weapons.” Wall Street Journal, January 4, 2007. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB116787515251566636.

Smetana, Michal, and Carmen Wunderlich. 2021. “Forum: Nonuse of Nuclear Weapons in World Politics: Toward the Third Generation of ‘Nuclear Taboo’ Research.” International Studies Review 23 (3): 1072–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab002.

Tabarrok, Alex. 2022. “What Is the Probability of a Nuclear War, Redux.” Marginal Revolution (blog). February 28, 2022. https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2022/02/what-is-the-probability-of-a-nuclear-war-redux.html.

Tannenwald, Nina. 2007. The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons Since 1945. Cambridge Studies in International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511491726.

UNODA, (United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs). 1968. “Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).” https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/.

———. n.d. “Nuclear Weapons.” Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/.

USC, (Union of Concerned Scientists). 2015. “Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons.” Union of Concerned Scientists. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/close-calls-nuclear-weapons.

———. n.d. “Nuclear Weapons.” Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.ucsusa.org/nuclear-weapons.

Wan, Wilfred. 2019. “Nuclear Risk Reduction: A Framework for Analysis.” UNIDIR. https://unidir.org/publication/nuclear-risk-reduction-framework-analysis.

Wells, Samuel F. 1981. “The Origins of Massive Retaliation.” Political Science Quarterly 96 (1): 31–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/2149675.

Wikipedia. n.d. “Deterrence theory”, subsection: “Nuclear deterrence theory”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deterrence_theory#Nuclear_deterrence_theory.

Wilson, Ward. 2008. “The Myth of Nuclear Deterrence.” The Nonproliferation Review 15 (3): 421–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700802407101.

WINS, (World Institute for Nuclear Security). n.d. “Knowledge Centre.” Article archive. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.wins.org/knowledge-centre/.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer. 2007. “The Bottom Line.” LessWrong, September 28. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/34XxbRFe54FycoCDw/the-bottom-line.

Appendix

An Appendix describing routes of investigation that I started and then abandoned is compiled here: What are the most promising strategies for preventing nuclear war?_Appendix [CERI 2022]

- ^

I owe the nuance to distinguish between “using”, “detonating”, and “deploying” nuclear weapons to conversations with academics working on nuclear issues. It is also recommended by Atkinson 2010: “Whether used or not in the material sense, the idea that a country either has or does not have nuclear weapons exerts political influence as a form of latent power, and thus represents an instance of the broader meaning of use in a full constructivist analysis.”

- ^

In a previous draft, I wrote “use nuclear weapons in war” to convey the same meaning; I tried to replace this throughout the essay, but the old formulation may still crop up and should be treated as synonymous with “deploying” or “employing nuclear weapons”.

- ^

Similar arguments have been made by others, see for instance Fisher 1981 and Roser 2022.

- ^

This might be different for “the EA community working on nuclear risks”.

- ^

I rely on a common definition of risk, which basically says risk = harm*p(harm occurring). My focus on the probability part is grounded in a belief that intervening on the severity of the harm incurred is infeasible and potentially dangerous (because it can distract from other actions and especially because it may backfire, through moral hazard and/or normative shifts); I go into this a bit more in-depth in the previously mentioned write-up on why to care about the “prevent nuclear war” goal in the first place.

- ^

This would certainly include the path laid out in the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and might also include the working portfolio of some larger non-governmental organizations working on nuclear affairs (e.g., NTI), the nuclear doctrines of some states at some given point in time (e.g., minimum deterrence), specific strategies for preventing nuclear war written out in reports (e.g., see the Theory of Change of the MacArthur Foundation’s Nuclear Challenges Big Bet: 2020 Evaluation Report (Gienapp et al. 2020), or UNIDIR’s recent report on Nuclear Risk Reduction (Wan 2019)), or specific academic theories for what makes nuclear war more or less likely (e.g., Lodgaard 2009).

- ^

For instance, the NPT regime recommends/demands measures to stabilize deterrence as well as to eventually achieve complete nuclear disarmament.

- ^

Some argue that it is most stable if two countries with roughly equal nuclear weapons capabilities face each other, some argue that it is more stable if all major (and “responsible”) actors on the world stage possess these weapons (thus precluding the need for “extended deterrence” / a “nuclear umbrella”, which is considered less credible than direct deterrence), some go as far as to suggest that as many actors as possible should have the weapons, and some go to the other extreme, arguing that it is best if one actor has clear nuclear superiority and can reliably deter all the other (less responsible/reliable) countries. For an extensive survey of the debate on this topic (the so-called nuclear optimism/pessimism debate), see Lavoy 1995.

- ^

On the lower end sits the concept of minimum deterrence which calls for a small number of nuclear weapons, stored in a way such that they cannot be destroyed in a first strike and capable of inflicting substantial damage if directed against a few major cities (Forsyth et al. 2010). A more expansive strategy is massive retaliation, which requires sufficient forces to destroy a plethora of “enemy” cities and industrial centers (Wells 1981, p. 34). Beyond these more “simple” deterrence concepts lie counterforce strategies, which are geared towards fighting nuclear wars at varying levels of escalation and thus demand a differentiated arsenal of nuclear weapons and create pressure to attain superiority over (or at least prevent inferiority to) the arsenal of possible opponents (for an early example of such a proposal, see Buzzard 1956; for a critical analysis of the counterforce approach, compare McDonough 2006).

- ^

These include trust and emergency communication lines between nuclear weapons state decision-makers, measures to increase the safety and reliability of the weapons infrastructure (including sensors that detect incoming missiles), and “prudent nuclear postures” (e.g., de-alerting of weapons, non-aggressive rhetoric surrounding the deployment of nuclear weapons), among others.

- ^

- ^

For one such critic, see Wilson 2008.

- ^

As argued by, among others, Perkins 1985.

- ^

A point made, for instance, by Ikle 1972, p. 269.

- ^

A discussion of competing accounts is given in Legro 1997.

- ^

An example of such a contestation of the nuclear taboo and its effects is Davis Gibbons and Lieber 2018.

- ^

A relatively recent special issue in the International Studies Review (Smetana and Wunderlich 2021) gives a good overview of the literature on the pathways through which norms may be influential.

- ^

I explicitly don’t include the safety of civilian nuclear power infrastructures in my use of the term here; this doesn’t necessarily mean that I think the topic irrelevant, just that it is outside the scope of this write-up on “reducing the probability of nuclear war”.

- ^

The report by the Union of Concerned Scientists referenced before (USC 2015), for instance, features this proposal.

- ^

The work and commentary of the World Institute for Nuclear Security give a good illustration of what the term refers to in practice.

- ^

The critique can be found, for instance, in this 2018 book on “Nuclear Apartheid” by Saghir Iqbal, or this 2005 article on “Organized Hypcrisy and the NPT” by Michael Lipson.

- ^

I have not engaged with that debate a lot, and might be missing important nuances in this brief outline. I welcome feedback with suggestions for how to expand my list of follow-on cruxes!

- ^

For instance, Dexter Masters and Katherine Way’s One World or None from 1946 argued that the contemporary world order was not fit to deal with the existence of nuclear weapons and called for a world government to control them.

- ^

An example of this is Bertrand Russell’s Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare (1959), for instance on pp. 46-47: “First, as the experience of the last thirteen years has shown, disarmament conferences cannot reach agreements until the relations of East and West become less strained than they have been; second, the long-run problem of saving mankind from nuclear extinction will only be postponed, not solved, by agreements to renounce nuclear weapons. Such agreements will not, of themselves, prevent war, and, if a serious war should break out, neither side would consider itself bound by former agreements [...] For these reasons, I should regard agreed disarmament as a palliative rather than a solution.”

- ^

One example for such moderate efforts is the Nuclear Threat Initiative’s “Dialogue on the Future of U.S.-Russia Nuclear Cooperation” initiative (Holgate and Newman n.d.).

- ^

One of the more recent advocates for this option is Craig 2020.

- ^

This is exemplified in the crusade against “nuclearism” fought by proponents of the Treaty on the Prohibition on Nuclear Weapons; e.g., see Falk 2017.

- ^

One example is a book chapter by Leveringhaus and Hussell (2017), which calls for a “concert of power” between NWS to manage the nuclear order.

- ^

This is the core recommendation of the (Neo-)Liberal school in International Relations theory, described, for instance, in Rauchhaus 2009, p. 259)

- ^

Among the most prominent advocates for the approach to reduce nuclear risks by tackling the inequalities and injustices inherent in the status quo of the current nuclear order (which is marked by a division between states who do and those who don’t own nuclear weapons, and by a division between decision-making elites and the people who are most vulnerable to the effects of nuclear weapons policies) are postcolonial scholars, an example of who is Mathur 2016.

- ^

A summary of different attempts to understand whether an inter-state world with one, two or several poles of power is more likely to result in war is given in Cashman 2013, p. 401 (referenced in Clare 2021, p. 35). That same author concludes that none of these attempts yields conclusive insights and that we thus essentially know very little about whether and how the distribution of power between nation-states affects the prevalence and severity of armed conflict.

- ^

See the United Nations Disarmament Office’s website, or this speech by then-General Secretary Ban Ki-Moon (2008).

- ^

Prominent examples include individuals like former high-level politicians Shultz, Kissinger, Perry and Nunn (2007) and scientists (often speaking out through the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists or the Union of Concerned Scientists (USC)), as well as organizations like the Nuclear Threat Initiative, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. Out of the seventeen NGOs that I looked at in a study of highly-funded organizations with a primary focus on nuclear issues (listed in a map that the Peace and Security Funders Group put together), eleven claim on their websites that nuclear disarmament is at least one of their goals.

- ^

A few arbitrarily selected examples from the academic literature include Sauer, Kustermans and Segaert 2020, Rydell 2018, Kelleher and Reppy 2011, and Noel-Baker 1958.

- ^

As pointed out by Lodgaard (2009, p. 142): “[Nuclear disarmament] may be taken to mean no deployed weapons; no stockpiled weapons; no assembled weapons; no nuclear weapons in the hands of the military (but possible under civilian governmental control as an insurance premium); or no national nuclear weapons (but possibly nuclear weapons controlled by an international body).”

- ^

Among other things, commentators disagree about whether movements towards disarmament should be incremental vs. radical, whether there should be clear timelines and milestones vs. a more ad hoc process, and whether nuclear-weapons states should be induced to disarm through persuasion and cooperative engagement vs. through outside pressure and confrontation.

- ^

Resistance can be based in a desire for just treatment, aspirations to status/prestige, or a sense of fear and vulnerability.

- ^

The former seems obviously true, the latter is contested (see Brito and Intriligator 1996 for a summary of the debate on how nuclear proliferation affects the likelihood of war).

- ^

Both of these claims in combination are brought forth, for instance, by former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Nobel Price winner Hans Bethe (1986) and by current President of the Nuclear Threat Initiative Joan Rohlfing (2021), as well as by academics such as Scott Sagan (e.g., in a book documenting his debate with Kenneth Waltz on the risk or promise resulting from nuclear proliferation, 1995).

- ^

Unless changes in the world make it such that deterrence grows more reliable and/or accidents less likely. For instance, I have heard people discount this argument for nuclear disarmament based on the claim that transformational developments in artificial intelligence technologies are likely to resolve the nuclear challenge at some point in the next few decades.

- ^

Summarized concisely on the website of ICAN (the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons): “Nuclear weapons are the most inhumane and indiscriminate weapons ever created. They have catastrophic humanitarian and environmental consequences that span decades and cross generations; they breed fear and mistrust among nations, as some governments can threaten to wipe out entire cities in a heartbeat; the high cost of their production, maintenance and modernisation diverts public funds from health care, education, disaster relief and other vital services.”

- ^

What are the consequences of pursuing each of the strategies identified?, etc.

- ^

How should we proceed when action is urgently needed but cannot be grounded in robust/strong/conclusive evidence about the action’s consequences?, Which kind of evidence can give valid and relevant insights into the substantive question of how to prevent nuclear war?, etc.

- ^

Did I just write the bottom line before starting the investigation (Yudkowsky 2007) and then proceed to bolster and further rationalize my already-existing views? Not consciously, but I do see how you could conclude that this is what happened ^^’

Excellent post!

Regarding the political feasibility of nuclear disarmament, it is notable that political parties have in the past advocated for unilateral disarmament, in the wake of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Perhaps the most prominent was UK's Labour, from 1982 to 1990. Needless to say the sample size is small and there are many factors as plays but to cut the story short they got hammered for this and lost both major elections they contested advocating for this policy by a large margin. I am fairly confident Labour itself sees dropping the policy as one of the reasons they were eventually able to regain power. (Not even Corbyn dared bring it back)

This failure was partly due to a more general perception of Labour as "soft" on defense and communism in those years.

This can be contrasted with Ronald Reagan who was able to gain major traction for disarmament by coordinating with the Soviet Union in the 1980s. Yet he had campaigned as a hawk , in fact was initially seen by disarmament advocates as a potential nuclear madman himself.

Possible takeaways would be

1) Committing to disarmament during electoral campaigns is risky -> campaigns should focus on leaders who are already in power

2) Coordinated action by the biggest nuclear powers is likely to be more effective than unilateral action by the smallest

3) Political credibility creates room to negotiation. To be able to make compromises on nuclear weapons, political leaders first need to send the message that they definitely would press the button if the situation called for it.