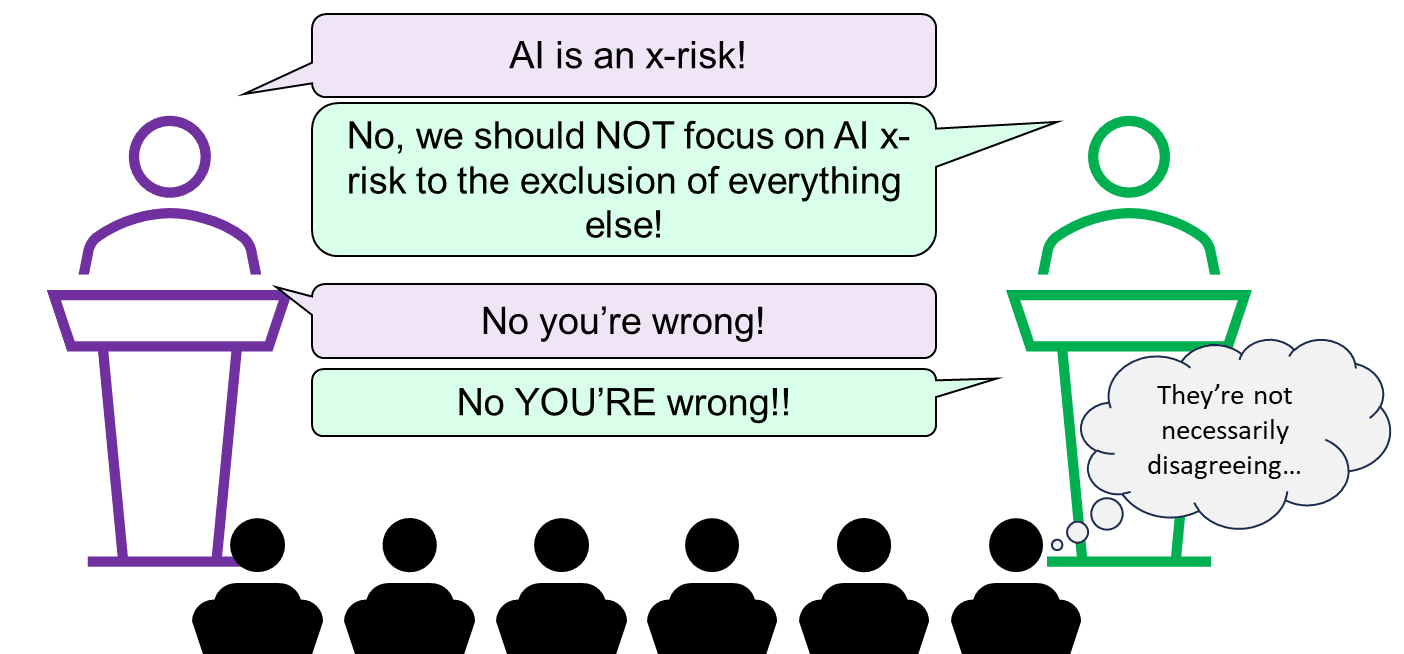

There was a debate on the statement “AI research and development poses an existential threat” (“x-risk” for short), with Max Tegmark and Yoshua Bengio arguing in favor, and Yann LeCun and Melanie Mitchell arguing against. The YouTube link is here, and a previous discussion on this forum is here.

The first part of this blog post is a list of five ways that I think the two sides were talking past each other. The second part is some apparent key underlying beliefs of Yann and Melanie, and how I might try to change their minds.[1]

While I am very much on the “in favor” side of this debate, I didn’t want to make this just a “why Yann’s and Melanie’s arguments are all wrong” blog post. OK, granted, it’s a bit of that, especially in the second half. But I hope people on the “anti” side will find this post interesting and not-too-annoying.

Five ways people were talking past each other

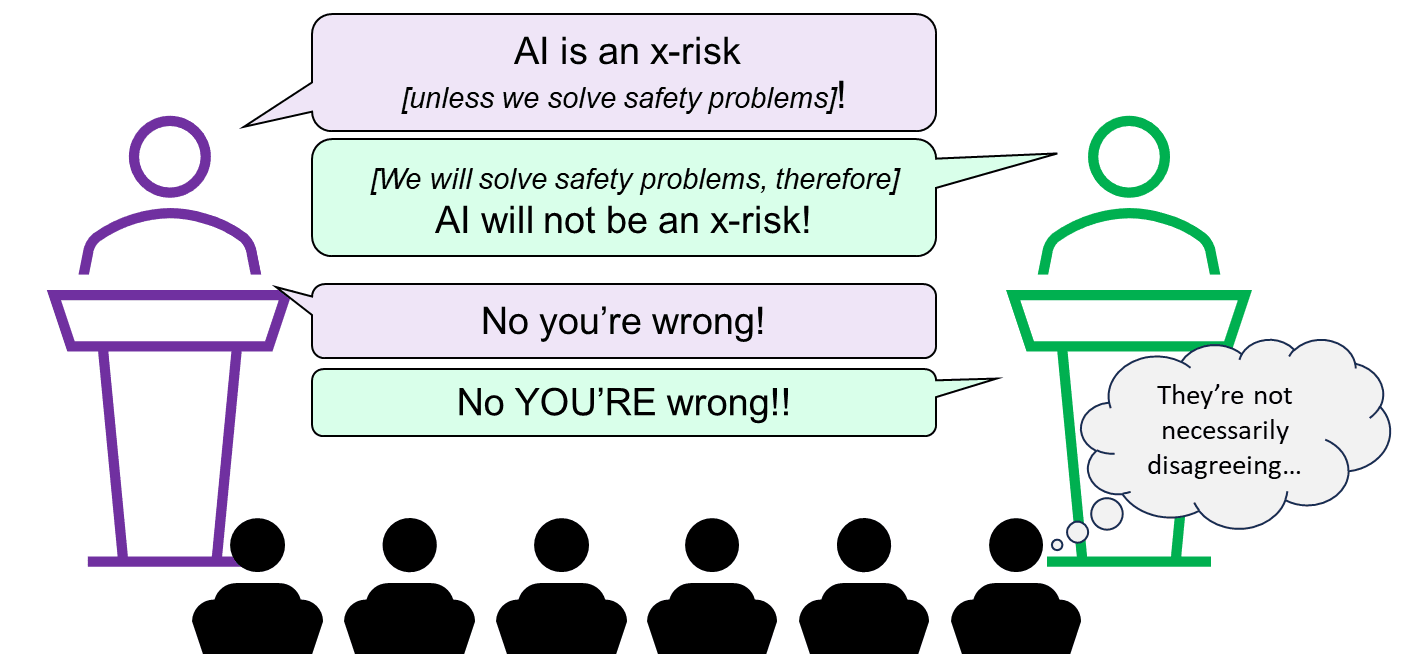

1. Treating efforts to solve the problem as exogenous or not

This subsection doesn’t apply to Melanie, who rejected the idea that there is any existential risk in the foreseeable future. But Yann suggested that there was no existential risk because we will solve it; whereas Max and Yoshua argued that we should acknowledge that there is an existential risk so that we can solve it.

By analogy, fires tend not to spread through cities because the fire department and fire codes keep them from spreading. Two perspectives on this are:

- If you’re an outside observer, you can say that “fires can spread through a city” is evidently not a huge problem in practice.

- If you’re the chief of the fire department, or if you’re developing and enforcing fire codes, then “fires can spread through a city” is an extremely serious problem that you’re thinking about constantly.

I don’t think this was a major source of talking-past-each-other, but added a nonzero amount of confusion.

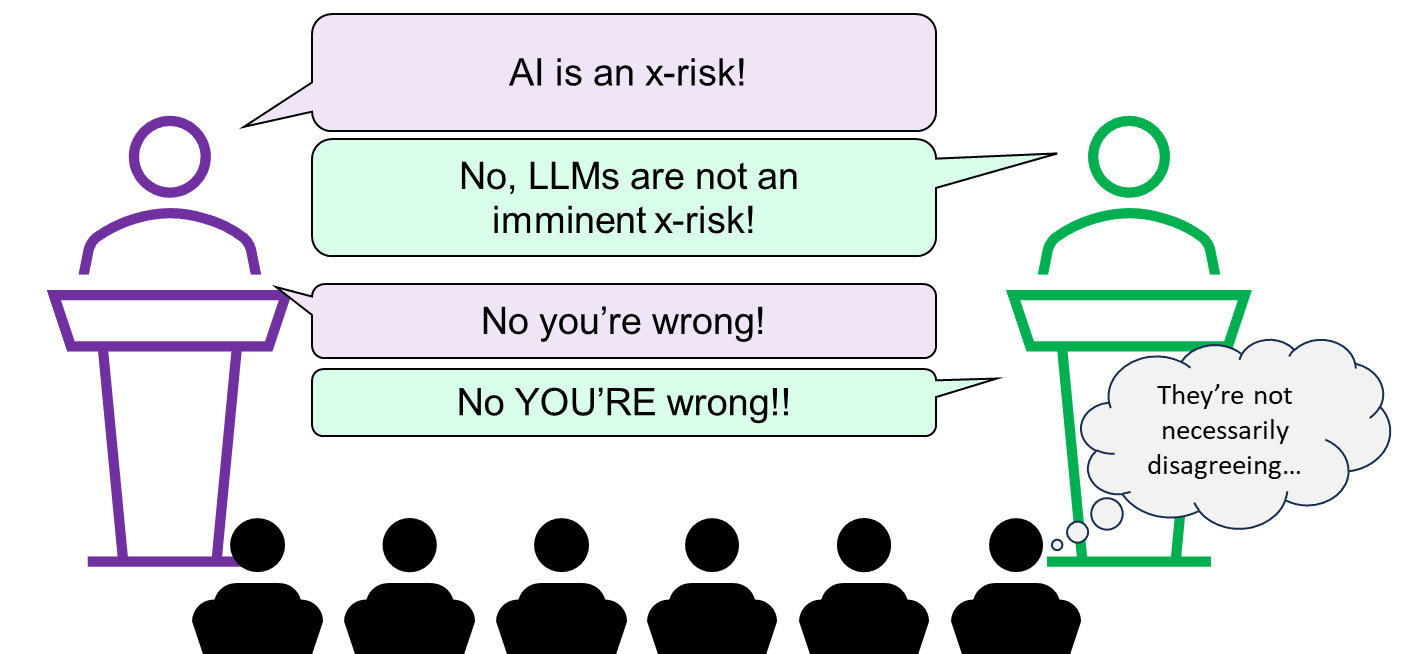

2. Ambiguously changing the subject to “timelines to x-risk-level AI”, or to “whether large language models (LLMs) will scale to x-risk-level AI”

The statement under debate was “AI research and development poses an existential threat”. This statement does not refer to any particular line of AI research, nor any particular time interval. The four participants’ positions in this regard seemed to be:

- Max and Yoshua: Superhuman AI might happen in 5-20 years, and LLMs have a lot to do with why a reasonable person might believe that.

- Yann: Human-level AI might happen in 5-20 years, but LLMs have nothing to do with that. LLMs have fundamental limitations. But other types of ML research could get there—e.g. my (Yann’s) own research program.

- Melanie: LLMs have fundamental limitations, and Yann’s research program is doomed to fail as well. The kind of AI that might pose an x-risk will absolutely not happen in the foreseeable future. (She didn’t quantify how many years is the “foreseeable future”.)

It seemed to me that all four participants (and the moderator!) were making timelines and LLM-related arguments, in ways that were both annoyingly vague, and unrelated to the statement under debate.

(If astronomers found a giant meteor projected to hit the earth in the year 2123, nobody would question the use of the term “existential threat”, right??)

As usual (see my post AI doom from an LLM-plateau-ist perspective), this area was where I had the most complaints about people “on my side”, particularly Yoshua getting awfully close to conceding that under-20-year timelines are a necessary prerequisite to being concerned about AI x-risk. (I don’t know if he literally believes that, but I think he gave that impression. Regardless, I strongly disagree, more on which later.)

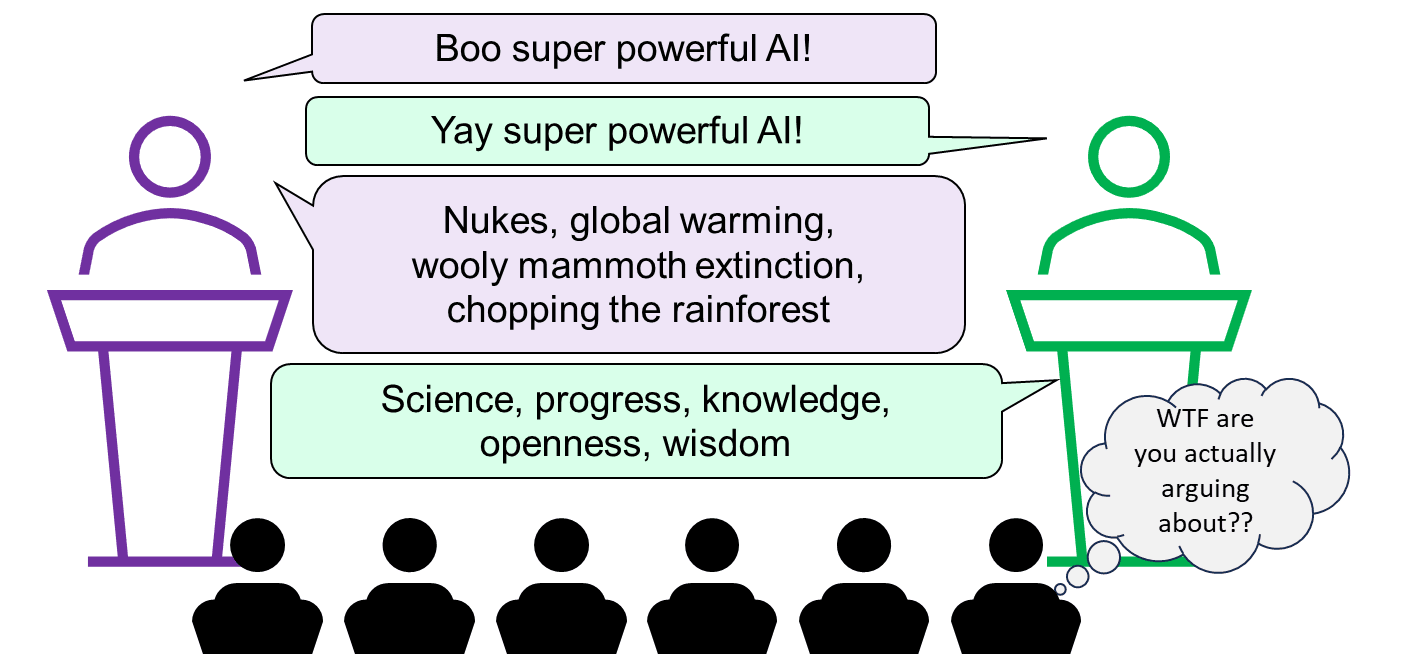

3. Vibes-based “meaningless arguments”

I recommend in the strongest possible terms that everyone read the classic Scott Alexander blog post Ethnic Tension And Meaningless Arguments. Both sides were playing this game. (By and large, they were not doing this instead of making substantive arguments, but rather they were making substantive arguments in a way that simultaneously conveyed certain vibes.) It’s probably a good strategy for winning a debate. It’s not a good way to get at the truth.

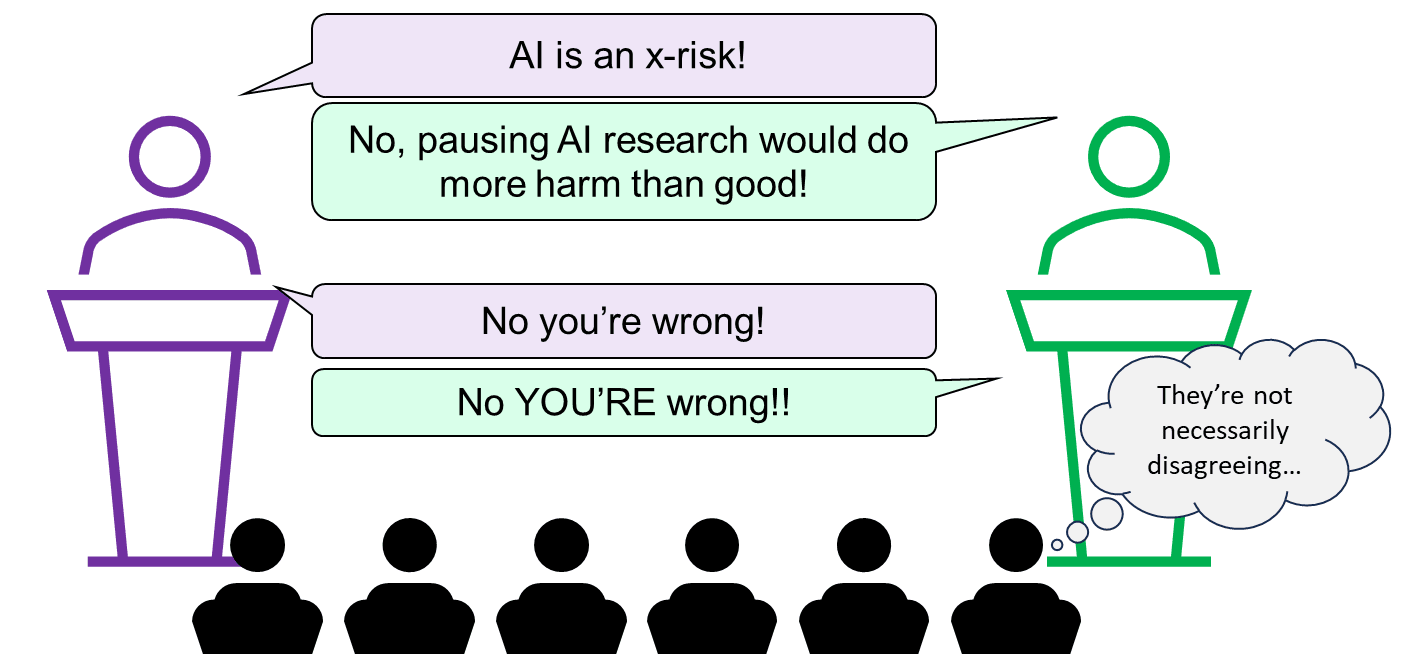

4. Ambiguously changing the subject to policy

The question of what if anything to do about AI x-risk really ought to be separate and downstream from the question of whether AI x-risk exists in the first place. Alas, all four debaters and the moderator frequently changed the subject to what policies would be good or bad, without anyone seeming to notice.

Regrettably, in the public square, people often seem to treat the claim “I think X is a big problem” as all-but-synonymous with “I think the government needs to do something big and aggressive about X, like probably ban it”. But they’re different claims!

(I think alcoholism is a big problem, but I sure don’t want a return to Prohibition. I think misinformation is a big problem, but I sure don’t want an end to Free Speech. More to the point, I myself think AI x-risk is a very big problem, but I happen to be weakly against the recently-proposed ban on large ML training runs.)

All four debaters on the stage were brilliant scientists. They’re plenty smart enough to separately track beliefs about the world, versus desires about government policy. I wish they had done better on that.

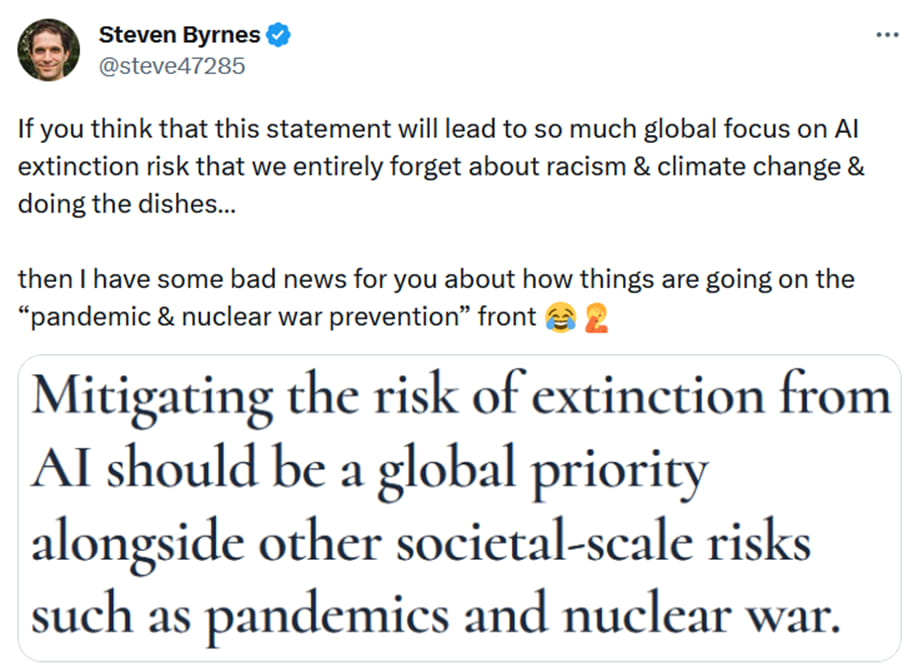

5. Ambiguously changing the subject to Cause Prioritization

Melanie pushed this line hard, suggesting in both her opening and closing statements that even talking about the possibility that AI might be an existential risk was a dangerous distraction from real immediate problems of AI misinformation and bias, etc.

I really don’t like this argument. I’ll pause for three bullet points to say why.

- For one thing, if we use that logic, then everything distracts from everything. You could equally well say that climate change is a distraction from the obesity epidemic, and the obesity epidemic is a distraction from the January 6th attack, and so on forever. In reality, this is silly—there is more than one problem in the world! For my part, if someone tells me they’re working on nuclear disarmament, or civil society, or whatever, my immediate snap reaction is not to say “well that’s stupid, you should be working on AI x-risk instead”, rather it’s to say “Thank you for working to build a better future. Tell me more!”

- For another thing, immediate AI problems are not an entirely different problem from possible future AI x-risk. Some people think they’re extremely related—see for example Brian Christian’s book. I don’t go as far as he does, but I do see some overlap. For example, both social media recommendation algorithm issues and out-of-control-AI issues are (on my models) exacerbated by the fact that huge trained ML models are very difficult to interpret and inspect.

- And lastly, this argument is assuming the falsehood of the debate resolution, rather than arguing for it. If AI in fact has a >10% chance of causing human extinction in the next 50 years (as I believe) then, well, it sure isn’t crazy to treat that as a problem worthy of attention! Yes, even if it were a distraction from other extremely serious societal problems!! Conversely, if AI in fact has a 1-in-a-gazillion chance of causing human extinction in the next 50 years, then obviously there’s no reason to think about that possibility. So, what’s the right answer? Is it more like “>10%”, or more like “1-in-a-gazillion”? That’s the important question here.

Some possible cruxes of why I and Yann / Melanie disagree about x-risk

Yann LeCun

Probably the biggest single driver of why Yann and I disagree is: Yann thinks he knows, at least in broad outline, how to make a subservient human-level AI. And I think his proposed approach would not actually work, but would instead lead to human-level AIs that are pursuing their own interests with callous disregard for humanity. I have various technical reasons for believing that, spelled out in my post LeCun’s “A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence” has an unsolved technical alignment problem.

If Yann could be sold on that technical argument, then I think a lot of his other talking points would go away too. For example, he argues that good people will use their powerful good AIs to stop bad people making powerful bad AIs. But that doesn’t work if there are no powerful good AIs—which is possible if nobody knows how to solve the technical alignment problem! More discussion in the epilogue of that post.

Melanie Mitchell

If I were trying to bridge the gap between me and Melanie, I think my priority would be to try to convince her of some or all of the following four propositions:

A. “The field of AI is more than 30 years away from X” is not the kind of claim that one should make with 99%+ confidence

I mean, 30 years is a long time. A lot can happen. Thirty years ago, deep learning was an obscure backwater within AI, and meanwhile people would brag about how their fancy new home computer had a whopping 8 MB of RAM.

Melanie thinks that LLMs are a dead end. That’s fine—as it happens, I agree. But it’s important to remember that the field of AI is broad. Not every AI researcher is working on LLMs, nor even on deep learning, even today! So, do you think getting to human-level intelligence requires better understanding of causal inference? Well, Judea Pearl and a bunch of other people are working on that right now. Do you think it requires a hardcoded intuitive physics module? Well, Josh Tenenbaum and a bunch of other people are working on that right now. Do you think it requires embodied cognition and social interactions? Do you think it requires some wildly new paradigm beyond our current imagination? People are working on those things too! And all that is happening right now—who knows what the AI research community is going to be doing in 2040?

To be clear, I am equally opposed to putting 99%+ confidence on the opposite kind of claim, “the field of AI is LESS than 30 years away from X”. I just think we should be pretty uncertain here.

B. …And 30 years is still part of the “foreseeable future”

For example, in climate change, people routinely talk about bad things that might happen in 2053—and even 2100 and beyond! And looking backwards, our current climate change situation would be even worse if not for prescient investments in renewable energy R&D made more than 30 years ago.

People also routinely talk 30 years out or more in the context of building infrastructure, city planning, saving for retirement, etc. Indeed, here is an article about a US military program that’s planning out into the 2080s!

C. “Common sense” has an ought-versus-is split, and it’s possible to get the latter without the former

For example, “mice are smaller than elephants” is an “is” aspect of common sense, and “it’s bad to murder your friend and take his stuff” is an “ought” aspect of common sense. I find it regrettable that the same phrase “common sense” refers to both these categories, because they don’t inevitably go together. High-functioning human sociopaths are an excellent example of how it is possible for there to be an intelligent agent who is good at the “is” aspects of common sense, and is aware of the “ought” aspects of common sense, but is not motivated by the “ought” aspects. The same can be true in AI—in fact, that’s what I expect without specific effort and new technical ideas.

D. It is conceivable for something to be an x-risk without there being any nice clean quantitative empirically-validated mathematical model proving that it is

This is an epistemology issue, I think best illustrated via example. So (bear with me): suppose that the astronomers see a fleet of alien spaceships in their telescopes, gradually approaching Earth, closer each year. I think it would be perfectly obvious to everyone that “the aliens will wipe us out” should be on the table as a possibility, in this hypothetical scenario. Don’t ask me to quantify the probability!! But “the probability is obviously negligible” is clearly the wrong answer.

And yet: can anyone provide a nice clean quantitative model, validated by existing empirical data, to justify the claim that “this incoming alien fleet, the one that we see in our telescopes right now, might wipe us out” is a non-negligible possibility? I doubt it![2] Doesn’t mean it’s not true.

Well anyway, forecasting the future is very hard (though not impossible). But to do it, we need to piece together whatever scraps of evidence and reason we have. We can’t restrict ourselves to one category of evidence, e.g. “neat mathematical models that have already been validated by empirical data”. I like those kinds of models as much as anyone! But sometimes we just don’t have one, and we need to do the best we can to figure things out anyway.

None of this is to say that we should treat future advanced AI as an x-risk on a lark for no reason whatsoever! See the epilogue here for a pretty basic common-sense argument that we should be thinking about AI x-risk at all, as an example. That’s just a start though. Getting to probabilities of extinction in different scenarios is much more of a slog, e.g. we have to start talking about the technical challenges of making aligned AIs, and the social and governance challenges, and then things like offense-defense balance, and compute requirements, and fast versus slow “takeoff”, and on and on. There are tons of reasons and arguments and evidence that can be brought to bear in every part of that above discussion! But again, they are not the specific type of evidence that Melanie seems to be demanding, i.e. mathematical models that have already been validated by empirical data, and which can be directly applied to calculate a probability of human extinction.

(Thanks Karl von Wendt for critical comments on a draft.)

- ^

Note: For the purpose of this post, I’m mostly assuming that all four debaters were by-and-large saying things that they believe, in good faith, as opposed to trying to win the debate at all costs. Call me naïve.

- ^

Hmm, the best I can think of (in this hypothetical) is that we could note that “Earth species have sometimes wiped each other out”. And we could try to make a mathematical model based on that. And we could use the past history of extinctions as empirical data to validate that model. But the extraterrestrial UFO fleet is pretty different! We’re on shaky grounds applying that same model in such a different situation.

And anyway, if someone makes a quantitative model based on “Earth species have sometimes wiped each other out”, and if that counts as “empirically validated” justification for calling the incoming alien fleet an x-risk, then I claim that very same quantitative model should count as “empirically validated” justification for calling future advanced AI an x-risk too! After all, future advanced AI will probably have a lot in common with a new intelligent nonhuman species, I claim.

I wanted to skim this but accidentally read everything :) Great post! I think it's uniquely clear and interesting.

I did skim this,[1] but still thought it was an excellent post. The main value I gained from it was the question re what aspects of a debate/question to treat as "exogenous" or not. Being inconsistent about this is what motte-and-bailey is about.

Related words: argument scope, decoupling, domain, codomain, image, preimage

I think skimming is underappreciated, underutilised, unfairly maligned. If you read a paragraph and effortlessly understand everything without pause, you wasted an entire paragraph's worth of reading-time.

Hi Steven, thanks for what I consider a very good post. I was extremely frustrated with this debate for many of the reasons you articulate. I felt that the affirmative side really failed to concretely articulate the x-risk concerns in a way that was clear and intuitive to the audience (people we need good clear scenarios of how exactly step by step this happens!). Despite years (decades!) of good research and debate on this (including in the present Forum) the words coming out of x-risk proponents mouths still seem to be 'exponential curve, panic panic, [waves hands] boom!' Yudkowsky is particularly prone to this, and unfortunately this style doesn't land effectively and may even harmfully shift the overton window. Both Bengio and Tegmark tried to avoid this, but the result was a vague and watered down version of arguments (or omission of key arguments).

On the negative side Melanie seemed either (a) uninformed of the key arguments (she just needs to listen to one of Yampolskiy's recent podcast interviews to get a good accessible summary). Or (b) refused to engage with such arguments. I think (like a similar recent panel discussion on the lab leak theory of Covid-19) this is a case of very defensive scientists feeling threatened by regulation, but then responding with a very naive and arrogant attack. No, science doesn't get to decide policy. Communities do, whether rightly or wrongly. Both sides need to work on clear messages, because this debate was an unhelpful mess. The debate format possibly didn't help because it set up an adversarial process, whereas there is actually common ground. Yes, there are important near term risks of AI, yes if left unchecked such processes could escalate (at some point) to existential risk.

There is a general communication failure here. More use needs to be made of scenarios and consequences. Nuclear weapons (nuclear weapons research) are not necessarily an 'existential risk' but a resulting nuclear winter, crop failures, famine, disease, and ongoing conflict could be. In a similar way 'AI research' is not necessarily the existential risk, but there are many plausible cascades of events stemming from AI as a risk factor and its interaction with other risks. These are the middle ground stories that need to be richly told, these will sway decision makers, not 'Foom!'

Thanks!

Hmm, depending on what you mean by “this”, I think there are some tricky communication issues that come up here, see for example this Rob Miles video.

On top of that, obviously this kind of debate format is generally terrible for communicating anything of substance and nuance.

Melanie is definitely aware of things like orthogonality thesis etc.—you can read her Quanta Magazine article for example. Here’s a twitter thread where I was talking with her about it.

The objection here seems to be that if you present a specific takeover scenario, people will point out flaws in it.

But what exactly is the alternative here? Just state on faith that "the AI will find a way because it's really smart?" Do you have any idea how unconvincing that sounds?

Are we talking about in the debate, or in long-form good-faith discussion?

For the latter, it’s obviously worth talking about, and I talk about it myself plenty. Holden’s post AI Could Defeat All Of Us Combined is pretty good, and the new lunar society podcast interview of Carl Shulman is extremely good on this topic (the relevant part is mostly the second episode [it was such a long interview they split it into 2 parts]).

For the former, i.e. in the context of a debate, the point is not to hash out particular details and intervention points, but rather just to argue that this is a thing worth consideration at all. And in that case, I usually say something like:

Oh I also just have to share this hilarious quote from Joe Carlsmith:

Yeah, I think your version of the argument is the most convincing flavour. I am personally unconvinced by it in the context of x-risk (I don't think we can get to billions of AI's without making AI at least x-risk safe), but the good thing is that it works equally well as an argument for AI catastrophic risk. I don't think this is the case for arguments based on sudden nanomachine factories or whatever, where someone who realizes that the scenario is flimsy and extremely unlikely might just dismiss AI safety altogether.

I don't think the public cares that much about the difference between an AI killing 100% of humanity and an AI killing 50% of humanity, or even 1%, 0.1%. Consider the extreme lengths governments have gone through to prevent terrorist attacks that claimed at most a few thousand lives.

100% agree regarding catastrophe risk. This is where I think advocacy resources should be focused. Governments and people care about catastrophe as you say, even 1% would be an immense tragedy. And if we spell out how exactly (one or three or ten examples) of how AI development leads to a 1% catastrophe then this can be the impetus for serious institution-building, global cooperation, regulations, research funding, public discussion of AI risk. And packaged within all that activity can be resources for x-risk work. Focusing on x-risk alienates too many people, and focusing on risks like bias and injustice leaves too much tail risk out. There's so much middle ground here. The extreme near/long term division on this debate has really surprised me. As someone noted with climate, in 1990 we could care about present day particulate pollution killing many people, AND care about 1.5C scenarios, AND care about 6C scenarios, all at once, it's not mutually exclusive. (noted that the topic of the debate was 'extinction risk' so perhaps the topic wasn't ideal for actually getting agreement on action).

Yann talked at the beginning how their difference in perspectives meant different approaches (open source vs. control/pause). I think a debate about that would have probably been much more productive. I wish someone had asked Melanie what policy proposals as a consequence of x-risk would be counter to policies for the 'short term' risks she spoke of, since her main complaint seemed to be that x-risk was "taking the oxygen out of the room", but I don't know concretely what concerns from x-risk would actually hurt short-term risks.

In terms of public perception, which is important, I think Yann and Bengio came across as more likable (which matters), while Max and Melanie several times interrupted other speakers, and seemed unnecessarily antagonistic toward the others' viewpoints. I love Max, and think he did overall the best in terms of articulating his viewpoints, but I imagine that put some viewers off.

Great post!

A and B about 30 years are useful ideas/talking points. Thanks for the reminder/articulation!