When technology takes a leap in innovation, such as with cryptocurrency, existing institutions are forced to play catch-up with education and regulations.

Cryptocurrency and Web3 enable improved privacy, censorship resistance, fewer intermediaries and data ownership. Unfortunately, an increase in privacy and a decrease in censorship make cryptocurrency and Web3 attractive ecosystems for malicious actors. Cryptocurrency has made it easier to profit from activities that create suffering (human trafficking, child abuse materials, terrorist financing) by making money laundering more accessible. Additionally, cryptocurrency has made sanctions less effective, allowing certain nation states to effectively avoid sanctions by leveraging the anonymity cryptocurrency provides.

The technology comes first, the regulations come second. Because of the lack of regulations and institutional understanding surrounding cryptocurrency, criminals are turning away from traditional banking systems and into crypto ecosystems. To prevent S- and X-Risks arising from new technology, institutions cannot rely on reactivity, but must anticipate what new technologies are possible, the risks of those technologies, and the types of regulations that can proactively mitigate those risks without sacrificing too much individual freedom.

One lesson that can be learned from observing the emergence of cryptocurrency is that when there are no regulations promoting safety, innovators in technology will make mistakes that can give enormous power to malicious actors, as was seen in the Lazarus (DPRK) Heists that have totaled ~$1.75 Billion[1]. The world has witnessed Lazarus (a Cybercrime group run by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea) quickly learn the cryptocurrency ecosystems and successfully identify opportunities for exploitation. Lazarus has found success in socially engineering[2] attacks on bridges[3], which connect different parts of the cryptocurrency and Web3 ecosystems. Lazarus did not have to be so technologically advanced as to invent cryptocurrency; they only needed to learn enough to be able to find and exploit its vulnerabilities. We must closely observe the response of totalitarian states to technological advancements to anticipate their future responses when the stakes might be considerably higher.

Observing malicious actors in cryptocurrency can provide insights for the importance of proactive policy in helping emerging technology be resistant to exploits. For example, even if we can build extremely safe Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), a totalitarian state or terrorist group would only need to find a single vulnerability to weaponize the technology. We cannot merely build AGI safely; it must also be sufficiently difficult to alter or re-educate the AGI. Therefore, technological innovators should be incentivized to seriously consider exploitation vulnerabilities, especially when the technology touches sources of power, such as money, weapons or infrastructure. Paying attention to how illicit actors manipulate emerging technology for their own gain will be crucial to sufficiently mitigate the S- and X-Risks of future technology.

Currently, institutions are behind on understanding how emerging technology can be used for malicious activity. This is evident when looking at cryptocurrency and the recent OFAC Sanction of Tornado Cash[4]. OFAC Sanctions come from the United States Department of Treasury and prohibit anyone in the United States from interacting with the sanctioned entity. The sanction on Tornado Cash is confusing at best, sanctioning just one part of the protocol in one ecosystem. Although Tornado Cash has certainly been utilized by many criminals, including Lazarus (DPRK), the illegality is in the theft and laundering of the crypto, not in the code (Tornado Cash) that was used to accomplish part of the laundering.

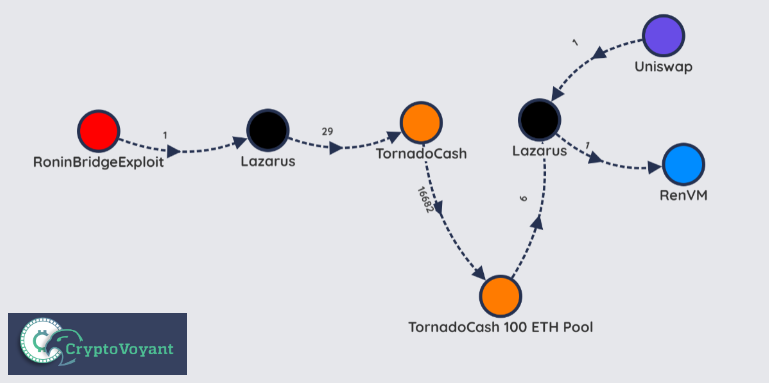

Regulations could be made to force privacy services (mixers, chain hoppers, coin swappers) to have KYC (Know Your Customer requirements) and AML (Anti-Money Laundering requirements) similar to the requirements of Money Service Businesses[5]. However, at the moment, the standards and regulations for on-chain services are not well defined, making it difficult to see how Tornado Cash, as a smart contract, is an illicit actor. Additionally, the focus on Tornado Cash seems arbitrary, with Lazarus (DPRK) repeatedly using a cryptocurrency ecosystem hopping service called RenVM, as well as swapping services, such as Uniswap, when laundering their stolen funds after a heist. Yet, neither RenVM nor Uniswap have been subject to sanctions.

Simplified view of one series of techniques Lazarus used to launder ~$600M from the Ronin Bridge Heist

Simplified view of one series of techniques Lazarus used to launder ~$600M from the Ronin Bridge Heist

It is unclear why the Department of Treasury only sanctioned one contract belonging to Tornado Cash, and why Tornado Cash was the only privacy service sanctioned. The Tornado Cash sanction can be related to attempting to take a stand against gun violence by banning one model of one type of gun, and not the entire gun at that, just the trigger. The Tornado Cash sanction shows that institutions are being reactive to the new risks emerging technology poses to society, and that in those reactions there is a perceived lack of understanding of the underlying technology.

There is currently a lawsuit that aims to remove Tornado Cash from the OFAC sanction list[6], and this lawsuit could set a legal precedent that could undermine future regulations. If we are to control and mitigate the risks of emerging technology, we must be careful with our legal action to not put ourselves in a position where all programming is free speech, therefore making it more difficult to regulate the programming of emerging technology such as AGI.

Cryptocurrency policy and regulations show how institutions currently are reactive rather than proactive in addressing major threats caused by advancing technology. Cryptocurrency and Web3 are the future, and there will be no stopping the adoption of this technology, just like there will be no stopping advancements in AI. Therefore, institutions must quickly become educated in emerging technology and attempt to predict both future innovations and their possible exploits if they want the best chance at mitigating S- and X-Risk.

Brewster, Thomas. “North Korean Hackers Accused of 'Biggest Cryptocurrency Theft of 2020'-Their Heists Are Now Worth $1.75 Billion.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 10 Feb. 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2021/02/09/north-korean-hackers-accused-of-biggest-cryptocurrency-theft-of-2020-their-heists-are-now-worth-175-billion/?sh=3b1236d85b0b. ↩︎

Lakshmanan, Ravie. “Hackers Used Fake Job Offer to Hack and Steal $540 Million from Axie Infinity.” The Hacker News, 11 July 2022, thehackernews.com/2022/07/hackers-used-fake-job-offer-to-hack-and.html. ↩︎

Ryan Browne, MacKenzie Sigalos. “Hackers Have Stolen $1.4 Billion This Year Using Crypto Bridges. Here's Why It's Happening.” CNBC, CNBC, 10 Aug. 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/08/10/hackers-have-stolen-1point4-billion-this-year-using-crypto-bridges.html. ↩︎

“U.S. Treasury Sanctions Notorious Virtual Currency Mixer Tornado Cash.” U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2 Sept. 2022, home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0916. ↩︎

“Money Services Business (MSB) Information Center | Internal Revenue Service.” Money Services Business (MSB) Information Center | Internal Revenue Service, www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/money-services-business-msb-information-center . Accessed 14 Sept. 2022. ↩︎

“Crypto Engineers, Investors Sue US Treasury Over Tornado Cash Sanctions.” Crypto Engineers, Investors Sue US Treasury Over Tornado Cash Sanctions, 8 Sept. 2022, www.coindesk.com/policy/2022/09/08/crypto-engineers-investors-sue-us-treasury-over-tornado-cash-sanctions . ↩︎