Note: This post is a synthesised version of this report, which analyses some public opinion polling we did for a disruptive climate-focused campaign in the UK, by Just Stop Oil. I think this might be relevant to EAs as I've generally perceived there to be quite a lot of skepticism about groups who employ "radical" tactics (e.g. disruptive protest) as it might taint a certain field, or otherwise slow overall progress. Whilst this work only answers the public opinion component of this concern, we find that radical tactics can actually increase support for and identification with more moderate organisations working on the same issue - a helpful dynamic. However, it's plausible that this works best for large social movements (e.g. the climate movement) where distinctions between a radical faction and moderate faction are much more clear. That said, we also found some trends towards polarisation that we intend to analyse further.

Summary

Social Change Lab conducted nationally representative YouGov surveys, before and after a week-long campaign by Just Stop Oil to block the M25 motorway. These surveys were conducted longitudinally, by surveying the same people before and after the Just Stop Oil M25 campaign. Our aim was to see if a ‘radical flank effect’ was at play: did the radical tactics implemented by Just Stop Oil impact attitudes towards more moderate UK climate organisations? We surveyed 1,415 members of the public about their support for climate policies and support for and identification with a more moderate climate organisation (Friends of the Earth). We detected a positive radical flank effect, whereby increased awareness of Just Stop Oil resulted in increased support for and identification with Friends of the Earth (p=0.004 and p=0.007 respectively).

We believe this is the first time the radical flank effect has been observed empirically using large-scale nationally representative polling, and it corroborates previous experimental findings by Simpson et al. (2022). The results indicate the potential positive effects of radical tactics on a broader social movement.

Support for climate policies also increased between our two surveys, though we attribute this largely to media coverage of COP27, which took place at the same time as the M25 protests. We believe this change was largely due to COP27 as we observed no positive correlation between awareness of Just Stop Oil and support for climate policies, and in fact, observed a statistically non-significant (p = 0.19) negative association.

Key Results:

- Over 92% of UK adults had heard of Just Stop Oil after their campaign, putting awareness of the organisation as high as the top 20 UK charities. This figure was 87% before this campaign started (as people may have reported higher awareness of Just Stop Oil purely due to our first survey). We think this value is very likely over-inflated but still shows fairly high awareness of Just Stop Oil.

- The number of people saying they support Friends of the Earth increased from 50.3% to 52.9% of the population, a 2.6 percentage point increase, equivalent to 1.75 million people in the UK.

- A clear positive radical flank effect: Increased awareness of Just Stop Oil after their M25 protest campaign was linked with stronger identification with and support for Friends of the Earth.

- A trend towards polarisation: Increased awareness of Just Stop Oil through their M25 campaign tended to make people who had low baseline identification with a moderate climate organisation reduce their support for climate policies; the opposite was true for people with high levels of baseline identification, who showed increased support for climate policies with increasing awareness of Just Stop Oil.

Introduction

Social movements are often made up of several factions, deploying diverse tactics. How these different factions interact and what an ‘optimal’ pursuit of different tactics might look like are currently open questions. One way to compare factions is to look at how radical their tactics are - that is, the extent to which they break social norms or cause disruption. The ‘Radical Flank Effect’ (RFE), coined by Haines (1984), is a theory of how more radical factions of a movement might impact more moderate factions. The RFE can be positive, whereby radical tactics increase support for more moderate groups, or negative, whereby radical tactics decrease support for the moderates. There has been little empirical work which looks directly at the RFE and the extent and direction (positive or negative) of its effect.

Those who argue for a positive radical flank effect claim that more radical groups make moderate groups seem more palatable by comparison. Within social movement advocacy, this strategy is also referred to as shifting the Overton Window. For example, Haines (1984) who analysed the funding of major civil flights organisations in the US in the 1960s, claims that the existence of more radical black organisations (such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Martin Luther King) led to an increase in funding for more moderate black organisations, such as NAACP, by white groups. Haines claims that, contrary to popular belief, there was no “white backlash” due to radical black organisations, but instead an influx of donations from white groups to moderate black organisations. Similarly, in experimental studies of the RFE looking at both climate and animal advocacy movements, Simpson et al. (2022) show that radical tactics can increase support for more moderate factions, through people identifying more with those moderate positions.

Proponents of the negative radical flank effect, such as Feinberg et al. (2019), suggest that extreme actions can alienate people and reduce identification with a movement. This effect can extend even to moderate groups, and so reduce overall support for a movement. Others, such as Ellefsen & Busher (2020) show that radical tactics can have other negative consequences, such as increased repression for a social movement.

As mentioned, there has been little empirical work on the impact of the radical flank effect. Whilst Simpson et al. (2022) finds experimental support for a positive RFE, it is not clear how well these findings extend to the real world. To our knowledge, there has been no attempt to measure the radical flank effect through large-scale nationally representative public opinion polling, for an ongoing campaign using radical tactics. Using a recent Just Stop Oil campaign in the UK, we sought to gain a clear understanding of the radical flank effect in practice.

Understanding the radical flank effect is particularly important now, since radical tactics are being used more and more, particularly by the climate movement. For example, since Extinction Rebellion’s conception in 2018, there has been a wave of new organisations such as Just Stop Oil, Last Generation, Save Old Growth, Fireproof Australia and more, who use civil disobedience and disruptive tactics to progress action on climate change. There is also an umbrella organisation, the A22 Network, which is a coalition of international climate groups pursuing disruptive nonviolent direct action as a key strategy. In addition, new funders, such as the Climate Emergency Fund, are increasingly funding this radical flank of the climate movement.

Methodology (synthesised)

We conducted a nationally representative survey, through YouGov, before and after a large direct action campaign by Just Stop Oil. The specific campaign by Just Stop Oil involved a week of blockading the M25 motorway that surrounds London. The campaign ran from Monday 7th November to Friday 11th November. Some media coverage also persisted after the end of the campaign.

This campaign was chosen for several reasons:

- First, we were informed this campaign would be happening on these dates. This meant we could conduct polling before the campaign began and measure baseline attitudes to Just Stop Oil, Friends of the Earth (the moderate faction), and other relevant metrics, such as support for climate policies.

- Secondly, Just Stop Oil protests are often disruptive and receive high levels of media and public attention. For instance, our April polling for Just Stop Oil found that over 60% of the UK public had heard of them. Their recent protest throwing soup at a Van Gogh painting was watched almost 50 million times on Twitter. High levels of campaign awareness are essential to detect the sort of population-level effects we are looking for.

- Thirdly, we knew this campaign was short (around a week) and clearly defined. This was important to reduce the impact of external factors which might also have an influence.

Our survey was conducted longitudinally, such that the same participants were contacted before and after the campaign. Our first survey on Friday 4th November had 1741 respondents, whilst our second, starting on Monday 14th and concluding on Monday 21st, had 1415 respondents. This equates to an overall retention rate of 81.3%.

Our key research questions were:

- Will increased awareness of Just Stop Oil, the radical faction, lead to increased identification with Friends of the Earth, the moderate faction?

- Will increased awareness of Just Stop Oil lead to higher levels of support for Friends of the Earth?

- Will increased awareness of Just Stop Oil lead to any change in support for climate policies?

Further information about our analyses and methodology can be seen in our pre-registration. The full list of questions asked can be seen here. All of the data and code used for this project can be found here. A short supplementary document with summary statistics and additional justification of the methodology can be seen here.

We used regression analyses to look at the degree to which people’s awareness of Just Stop Oil could predict their identification with Friends of the Earth, their support for Friends of the Earth, and their support for climate policies. The first set of analyses uses linear mixed effects models, a type of regression analysis that allows researchers to model variability within and between participants and items (see Brown, 2021 for an accessible introduction). The second set of analyses focused on the change in people’s responses before and after the protests - that is, one data point per respondent; this analysis involved conventional linear regression.

To correct for multiple comparisons within the six main analyses (two sets of three), we used Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

Results (synthesised)

Causal effects related to changes in awareness of Just Stop Oil due to the M25 protests

Just Stop Oil’s M25 protests were deliberately disruptive and received a lot of media attention. A striking 92.3% of respondents claimed to have heard at least to some extent about Just Stop Oil at T2. As such, it is plausible that they had an effect on people’s knowledge of and attitudes towards Just Stop Oil itself, as well as to Friends of the Earth (through the radical flank effect) and to climate policies more generally. Our results showed that from T1 (just before the protests) to T2 (just after the protests) there was an increase in the awareness of Just Stop Oil (T1 mean=2.71, T2 mean=2.92, p<0.001), an increase in people’s identification with (T1 mean=3.98, T2 mean=4.06, p=0.03) and support for Friends of the Earth (T1 mean=4.35, T2 mean=4.41, p=0.03), and increased support for climate policies (T1 mean=4.28, T2 mean=4.49, p<0.001).

This allowed us to look at whether people who were more aware of Just Stop Oil after the M25 campaign tended to identify more with Friends of the Earth and feel more supportive towards them. In doing this, we can be reasonably sure we are directly testing a radical flank effect: the two time points were only 10-15 days apart (depending on when participants completed the follow-up survey) which makes it very likely that any difference between those times is due to the protests (see the Limitations section for discussion).

We calculated difference scores for each variable (T2 minus T1), such that positive numbers reflect an increase over time and negative numbers reflect a decrease. In support of a positive RFE, linear regression analyses showed that increases in awareness of Just Stop Oil were linked with increases in identification with (estimate=0.14, SE=0.05, t=3.06, p=0.004) and support for Friends of the Earth (estimate=0.09, SE=0.03, t=2.79, p=0.007). In lay terms, this means there is a 0.4-0.7% chance that we observed results as extreme as this if no positive radical flank existed.

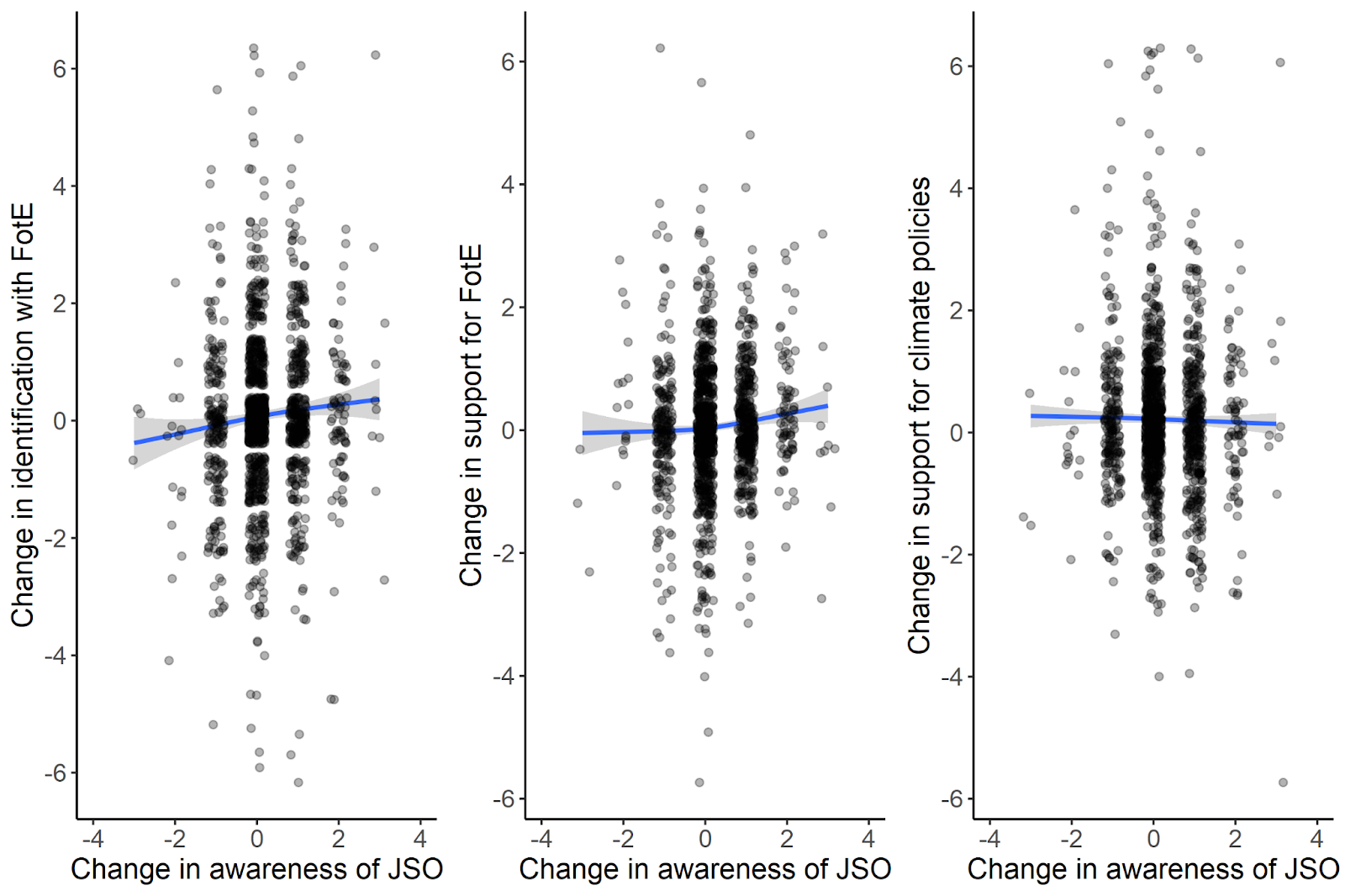

Figure 2: Effects related to changes in Just Stop Oil’s awareness. Increased awareness of JSO (after vs. before a week of protests) were associated with increased identification with (left panel) and support for Friends of the Earth (middle) and trended (non-significantly) towards a negative association with changes in support for climate policies (right).

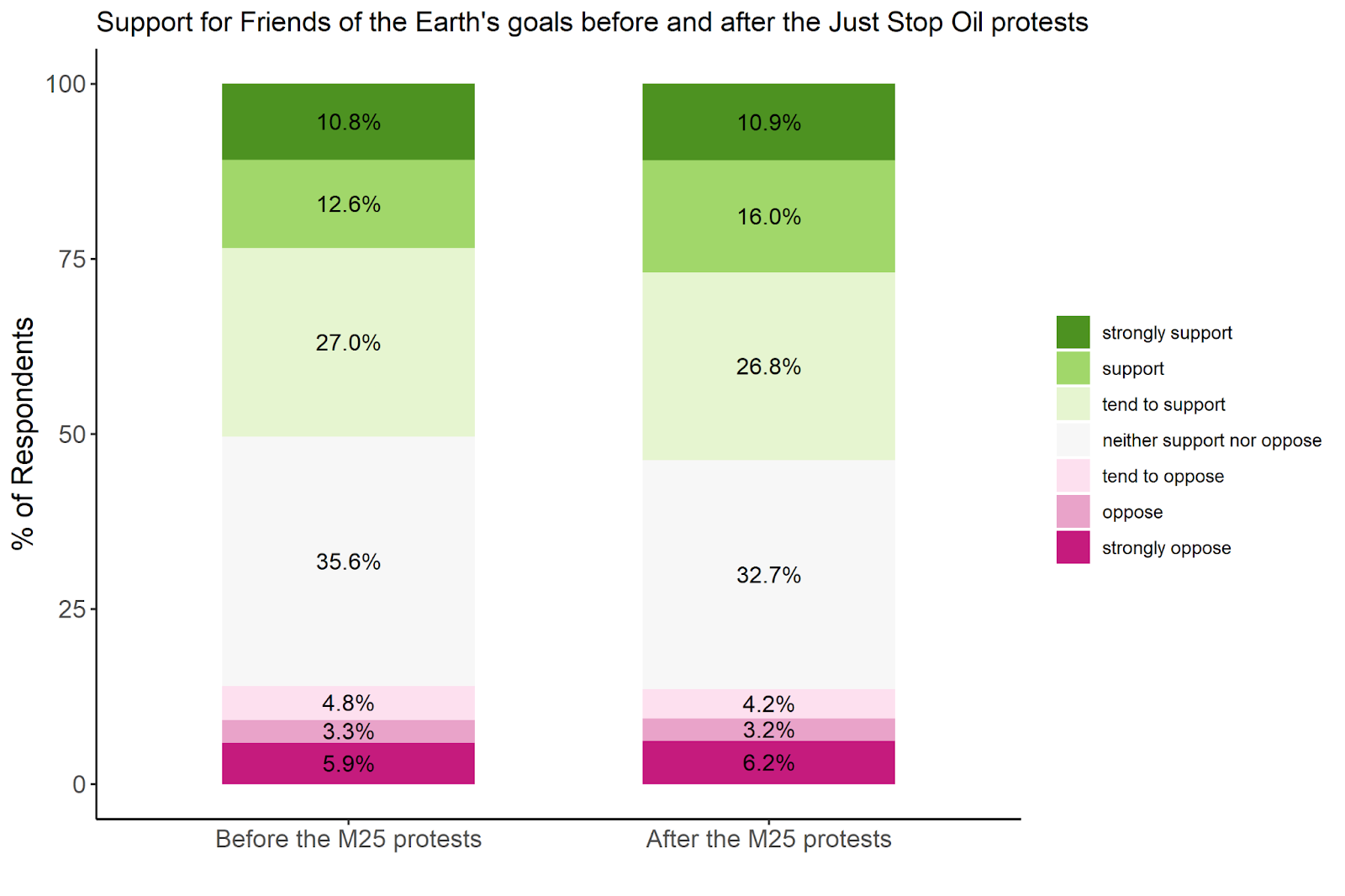

Figure 3 below shows more detail of the observed radical flank effect, whereby the percentage of people feeling neutral towards Friend of the Earth’s goals fell, and support for their goals increased. Over the two-week period we conducted our polling, the number of people saying that they supported Friends of the Earth’s goals increased from 50.4% of the UK population to 53.7%, a 3.3 percentage point increase. This is equivalent to 2.02 million additional people.

Figure 3: Change in support for Friend of the Earth’s goals (one variable which composed our overall support for Friends of the Earth composite variable) from before to after the M25 Just Stop Oil protests.

Relation between awareness of Just Stop Oil and support for climate policies

The results from the difference score analyses and the combined T1 and T2 analyses support a positive RFE; higher levels of awareness of a radical group were associated with stronger identification with and support for a moderate group with similar goals. We also tested whether increased awareness of Just Stop Oil was associated with stronger support for climate policies. This was not the case. Instead, in both types of analysis there was a non-significant trend towards a negative association (analysis 1 looking at overall effects: estimate=-0.05, SE=0.03, t=-1.73, p=0.10; analysis 2 looking at relative differences from before to after the campaign: estimate=-0.05, SE=0.04, t=-1.32, p=0.19). Overall, regardless of the change in awareness for Just Stop Oil, support for climate policies increased by a statistically significant amount between T1 and T2. We suggest that the media coverage around COP27 is likely to have been responsible for this increase (see Limitations section). When we looked at whether an increased awareness of JSO was associated with this stronger support for climate policy, we found that it was not. We discuss this counterintuitive combination of findings below..

These results indicate that a group utilising radical tactics may bring about two opposite effects concurrently. On the one hand, higher overall levels of awareness of Just Stop Oil were associated with stronger identification with and support for Friends of the Earth. More importantly, increased awareness of Just Stop Oil after a week of protests was associated with increased identification with and support for Friends of the Earth, a clear illustration of the positive radical flank effect. On the other hand, in both analyses (that is, looking at overall levels and at change between T1 and T2), there was a non-significant trend towards a negative effect on support for climate policies.

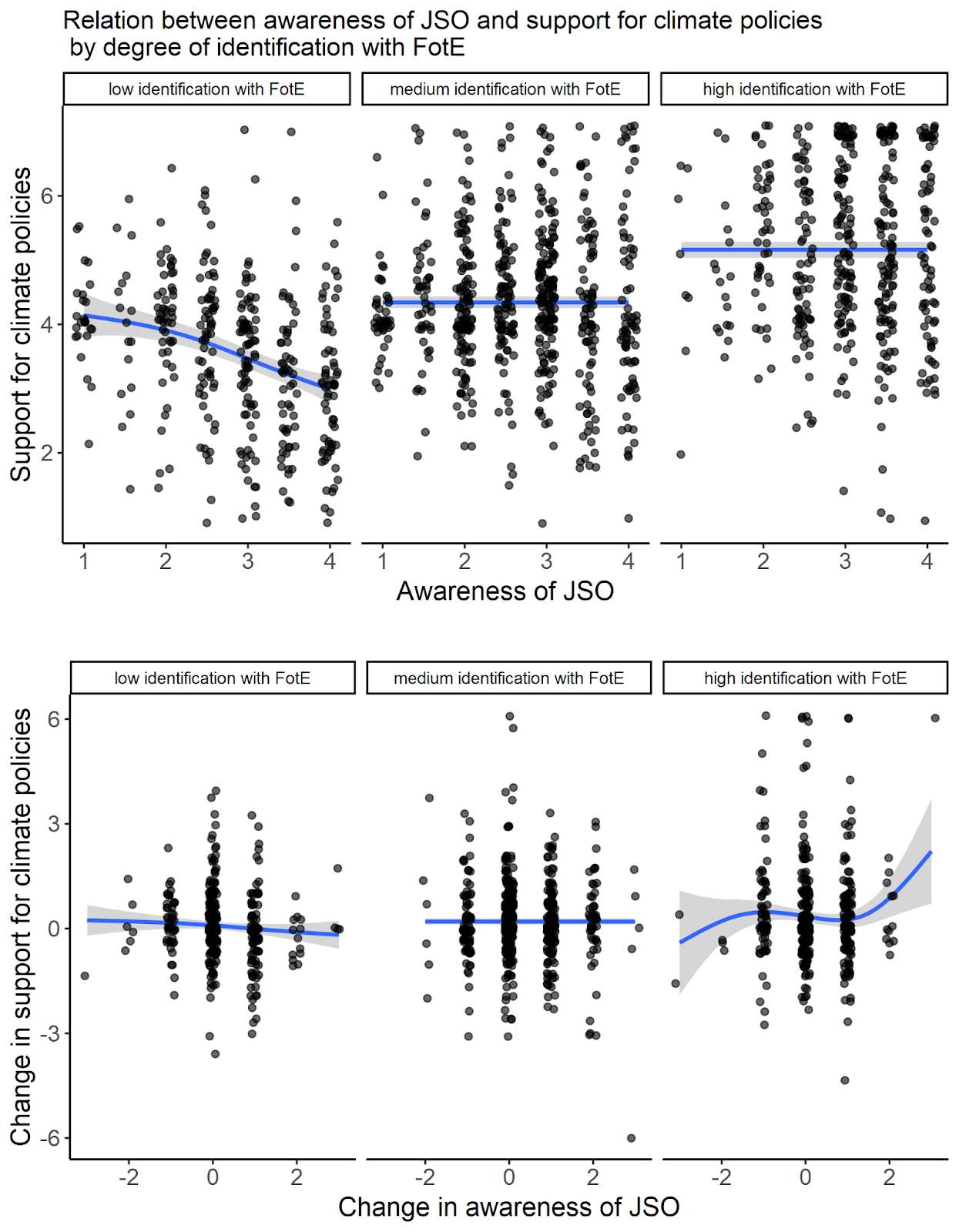

Why does increased identification with and support for Friends of the Earth not translate to support for climate policies? We might predict that it would, since the goals of Friends of the Earth resemble the climate policies people were asked about in the survey. Indeed, overall identification with and support for Friends of the Earth is correlated with support for climate policies in this survey. This initially confusing pattern can be explained by the fact that the overall results obscure what is going on for particular sub groups, whose behaviour is affected in different ways (see figure 4 below). To elaborate: generally, support for Friends of the Earth is linked with support for climate policies. Increased awareness of Just Stop Oil increases support for Friends of the Earth in some people and this likely also increases support for climate policies in those people. However, the relationship between these two factors is modest (see Figure 1, left and middle panels). This means that for many people, greater awareness of Just Stop Oil was not associated with greater support for Friends of the Earth. For these people, increased awareness of Just Stop Oil tends either to have no effect or to have a slightly negative effect on their support for climate policies. In both analyses (looking at overall levels and relative differences between T1 and T2), we see a possible negative effect specifically for people with overall low identification with Friends of the Earth and low support for climate policies (see bottom left panel in Figure 2). These are likely people who are generally more sceptical about climate change and about organisations working on it.

This suggests that a backfire effect of radical tactics might specifically exist for people who are more sceptical about the need to address climate change in the first place. We see an opposite trend for people who have high identification with Friends of the Earth to start with; for them, increased awareness of Just Stop Oil may lead them to support climate policies more (bottom right panel of Figure 4). A follow-up analysis showed that the effect of overall awareness of Just Stop Oil on overall support for climate policies (Figure 4, top part) was significantly modulated by the degree of identification with Friends of the Earth (interaction: p<0.001). Even though an equivalent analysis looking at the effect of changes in awareness of Just Stop Oil and changes in support for climate policies showed a similar trend (Figure 4, bottom), it was not statistically significant (interaction: p=0.14). From this, it seems that Just Stop Oil generates a small degree of polarisation, such that people who are already unsupportive of climate policies marginally reduce their support, and people who are already supportive, marginally increase their support. However, our data show these trends as quite weak in this particular campaign, so we are unsure about the extent of this effect.

Figure 4: Top row: Relation between overall awareness of Just Stop Oil and support for climate policies, plotted separately for people with low, medium, or high overall identification with Friends of the Earth. Bottom row: Relation between changes in awareness of Just Stop Oil and changes in support for climate policies before vs. after the M25 protests, plotted separately for people with low, medium, or high overall identification with Friends of the Earth.

Limitations

External factors, including COP27

Observational studies, such as this, have many advantages. For example, the protests we studied here presented a unique opportunity to investigate the previously hypothesised RFE in a large-scale nationally representative polling study, looking at a widely known ongoing campaign utilising radical tactics. However, the observational nature of the study also has disadvantages. COP27 was held from 6-18 November 2022 and thus overlapped with the JSO protests studied here. Media coverage of COP27 likely influenced responses in the survey, which was fielded on 4th of November and mostly completed by 18th November. For example, it is possible that COP27 coverage is the main reason that overall support for climate policies rose. Is it possible that what appears to be a positive RFE was actually due heightened attention on climate issues due to COP27? We think that overall increases in support for climate policies and increased support for Friends of the Earth could be attributed to COP27. However, awareness of Just Stop Oil was specifically linked with support for Friends of the Earth and not with support for climate policies more generally. This points to an independent effect: knowing more about Just Stop Oil leads the public to support Friends of the Earth more.

We plan to investigate this question further by analysing the amount of UK media coverage received by Just Stop Oil and COP27, to form estimates of the likelihood that changes in our variables were due to COP27 rather than the Just Stop Oil protests. Our conclusions about the finding of a RFE would also be strengthened by additional studies testing the RFE in different sociopolitical contexts.

Generalisability to other tactics

A second limitation concerns generalisability. Here, we focused on a particular week of protests, in which JSO blockaded the M25 by climbing on top of motorway gantries. This is a very particular kind of protest, involving very small numbers of people (often 1-2 people per gantry) causing a large amount of disruption to the public. It is hard to know whether we would observe a similar radical flank effect for different types of protests, with different numbers, different direct effects on the public, and so on. Throwing soup at paintings and blocking oil refineries are just two recent examples of very different kinds of radical actions. It is also unclear whether parallel negative effects might be seen: would a similar negative correlation (albeit a non-significant one) be seen between support for climate policies and awareness of other radical groups? Our previous polling about Just Stop Oil in April found no negative impact on support for climate policies. We speculate that this is because the April campaign focused on blockading oil depots and oil infrastructure, involved larger numbers and caused less direct disruption to the general public. Future studies using experimental and observational methods are needed to shed light on these sorts of questions.

Limitations of the study’s design

As our survey was a longitudinal study, it involved recontacting the same set of people for a follow-up survey. This has several implications that may affect some of our results, with the foremost issue being our finding that 92% of people had heard of Just Stop Oil after the M25 campaign. Whilst unlikely, it’s possible that the increase in awareness (from 87% to 92% of the UK population) of Just Stop Oil was partly due to participants remembering something about Just Stop Oil from our survey, consciously or subconsciously. As a result, this 92% might be slightly inflated, although we think this is neither a crucial finding nor likely to be a large effect, as participants probably understood us to mean if they had heard of Just Stop Oil, in the ‘real world’. Moreover, participation in our first survey might have meant that participants were more interested than normal in JSO’s activities, so they might have followed it more closely on the news or social media. As a result, our sample could have higher awareness of Just Stop Oil relative to the general population.

Additionally, it’s plausible that our survey served as a treatment in an experiment, by exposing people to both moderate and radical climate organisations back-to-back, such that the difference between them appears more stark. As a result, we might not expect to find results this extreme if not directly comparing Friends of the Earth to Just Stop Oil.

Discussion & Conclusion

Protest-focused social movements use a range of tactics in the hope of convincing other people of their cause with the ultimate goal of bringing about social change. It is still unclear what effects radical tactics have and the balance between positive and negative effects. Here, we focused on the radical flank effect, which proposes that disruptive activities of a radical faction alter support for more moderate groups in the same broader movement. Our results show that the extent to which people were aware of Just Stop Oil, a group employing radical protest tactics, affected their support for and identification with Friends of the Earth, a moderate group within the broader climate movement. Such a positive radical flank effect was observed in recent experimental research (Simpson et al., 2022). Experimental and observational studies have complementary strengths and weaknesses; experimental work is highly controlled and better able to rule out confounding factors and isolate specific active ingredients, while observational work can test how a certain phenomenon occurs in the real world, in the context of real protest movements. Convergence of results across research methods increases confidence in findings.

The radical flank effect we observed here was quite specific: awareness of Just Stop Oil was associated with increased identification with and support for Friends of the Earth but did not have a similar effect on support for climate policies. Instead, and particularly for people with low levels of support for climate policies to begin with, Just Stop Oil appeared to have had a slight negative effect on their climate attitudes. Specifically, it seems there was some polarisation generated by this campaign: people who were initially not very supportive of climate policies moved to support climate policies less, while those who were already supportive of climate policies trended in the opposite direction. This might be due to the specific tactics used by Just Stop Oil in this week-long campaign, which deployed small numbers of people to blockade a key UK motorway - a controversial tactic. We would like to repeat that this pattern was quite tentative and point out that in previous polling for Just Stop Oil, we found no negative impact on support for climate policies when large numbers of protesters targeted oil depots. Thus, more work is required to understand whether and in which circumstances polarisation and/or backfire effects due to radical tactics can occur.

We did not see a relationship between people’s awareness of Just Stop Oil and the extent to which they would be willing to act for Friends of the Earth (sign a petition, donate, or participate in an event). Thus, even though radical tactics may lead to more positive attitudes towards moderate factions, it is not entirely clear how this translates into tangible behavioural change. It is possible, though we cannot know without further research, that other effects develop over time. For instance, Just Stop Oil’s radical activities are likely to catalyse public debate of climate issues. To the extent that this leads to people becoming more informed about climate change, this could plausibly lead to higher degrees of concern for climate issues; previous research demonstrated that knowledge is an important driver of concern for climate change (Milfont, 2012). On the other hand, the lack of change in willingness to take climate action could be down to the tactics used. Whilst we didn’t see any changes in willingness to act for the M25 blockades, we did for Just Stop Oil’s campaign in April 2022 which directly targeted oil depots and other oil infrastructure. It is plausible that extremely high levels of public disruption were seen as less legitimate by the public, as opposed to targeted disruption of the oil industry, which in turn nullified any potential mobilising effects.

Contact us

We would appreciate any and all feedback on this, so please do leave comments below or reach out to us! If you have specific questions or want to talk more about our research, feel free to contact James at james@socialchangelab.org or Markus (who did all of the data analysis) at markus@socialchangelab.org. If you’re interested in funding our research or curious to hear more about our future plans, please contact James here.

As someone who had previously made news for a "radical climate protest" in my country back in 2020, I agree with this finding!

I’d like to share my own application of this phenomenon:

Case study: Climate protesting in Singapore

In 2019, the wave of global youth climate activism inspired by Greta Thunberg had spread to Singapore. Broadly speaking, Asian countries are generally underrepresented in climate activism, even in developed countries. [1]Consequently, the inaugural SG Climate Rally was relatively small at ~2,000 participants. I helped organise this rally.

There's a few things to note here:

Decision Matrix

From an x-risk prevention POV, the idea was to increase the probability of climate action by creating the threat of radical protests to supplement/increase support for moderate advocacy.

Basically, I did not think Radical > Moderate, but rather Radical+Moderate > Moderate Only.

EV calculations of "Radical" Climate Protests

I calculated the rough Expected Value (EV) of my climate protest as follows:

So, with about 2-3 orders of magnitude margin of error, I figured it was high-EV. After a big controversy and a year of organising, Singapore released climate goals that included a net zero goal by 2050, and a $80 carbon tax.

Further thoughts

I think a lot of people misinterpret advocacy, or at least climate advocacy.

Anyway, just sharing my (hopefully relevant) experience. I did do a lot of social movement research literature review while organising climate protests, so even this is a very small fraction of my thoughts on the topic. People seem to assume that activists are impulsive and have poorly-crafted theories of change, so it's hard to elaborate on reasoning when a critic just asserts that you're dumb.

Happy to engage with other discussions on this topic! Nowadays I work at Nonlinear mainly on AI Safety/meta stuff, so climate activism doesn't come up super often other than cross-applying x-risk theories of change.

The reason why is worthy of its own research/thread.

For previous grant-making decisions, I have been interested in the question about the extent to which more radical tactics can move the Overton Window and make things easier for more moderate activists. Based on fairly quick Google Scholar searches, I haven't found anything, so I'm glad you've investigated this.

I haven't read your piece fully, so sorry if I'm asking things which are answered in your post.

Hi Sanjay, thanks for the good questions! Since you said you were looking, the most relevant bit of research to this topic is by Simpson et al. (2022) who did experimental research on the radical flank effect, both for radical tactics and a radical agenda. Interestingly, they find that a radical agenda had no effect, but radical tactics did. On your questions:

Thanks for pointing me to Simpson et al 2022.

Ah I've understood you now! I don't see what you said being a problem as we explicitly put a sentence description in the survey for both JSO and Friends of the Earth explaining a tiny bit about who they were (e.g. they use radical tactics) without anchoring respondents too much. So I'm quite confident that respondents would have known JSO was utilising more disruptive tactics relative to Friends of the Earth. In addition, given how much media coverage JSO got during this week (and for previous actions) I would be quite surprised if a good proportion of people in the UK (50%+?) hadn't already seen some reference to JSO in the context of arrest, police or disruptive protest.

Agreed about the stated intentions vs action point. I think increasing support for a policy can be a useful public opinion signal, but JSO probably also wants increased desire to take action on climate change (e.g. sign a petition, attend protest, etc), which we didn't find a change in.

Nice! Very cool research idea and very interesting findings. From a skim and without having thought too hard about it, the methodology and setup seems more careful and higher quality than what I remember of your previous survey too, so nice job on that!

This roughly fits with my somewhat indirect inferences from some of the research I did on how media coverage and public opinion influence each other and policy-making. (Other relevant points here.) I'd expect more radical tactics to be good at forcing an issue onto the public and policy agenda, but not good (possibly counterproductive) at persuading unsupportive members of the public to change their mind. Your evidence on polarisation supports this, I think. And if it such protests do indeed increase support for more moderate groups, as your study suggests, then that gives them more influence to negotiate with policy-makers.

My inferences are getting even more indirect now, but an implication of this is that radical campaigns targeted towards issues that the public are already supportive of would be helpful for forcing change, but not so helpful and perhaps counterproductive on issues where there isn't already popular support. (This might be bad news for groups like Animal Rebellion.)

Thanks for the kind words! Our new Director of Research did all the analysis for this (I still did the methodology) and he's quite a whiz at data analysis, so he can take all the credit for that side of things!

Good to know that it fits in well with your previous findings. I also think this supports a similar loose set of hypotheses I had going into this.

Re it being less good for issues with low levels of public support, I think what you say is broadly true, with a caveat. I think for issues with low public support, it's not often that there is a big base of people who oppose an issue and we slowly win people other; Instead, I think it's more like that most of the population don't really have a view, and using radical tactics, you're getting them to actually form a view on an issue. I think the best example for me of this is the chart below, which shows public support for BLM (the group, not the issue) post-George Floyd protests. I think Animal Rebellion does similar stuff - It will turn a bunch of people off, it will probably attract some people, but ultimately it's getting a lot more people to actually take a stance. Obviously the balance of this is important, and something that it doesn't feel like we have great evidence on.

This is very cool, thanks for doing this research and sharing it.

Thanks for the comment Ben - that's very kind of you!

I think this is interesting research but I would quibble with your interpretation of the top part of figure 4 as a causal effect. As far as I can tell, that part is a cross-sectional analysis that is only valid if individuals with greater knowledge of climate organisations are the same in all relevant ways as those with lower levels of knowledge that identify with Friends of the Earth to the same extent. This seems unlikely to be true and indeed does not have to hold for the fixed effect analyses that make up the majority of this piece to be unbiased. If I have not misinterpreted something here, I would recommend being much clearer in future about when switching between fixed and random effects models as they estimate very different parameters, with fixed effects usually being much more reliable at retrieving causal effects.

Hi Joseph, thanks for your comment! It might have been a misunderstanding but we're definitely not claiming the top panel of Figure 4 is causal. It might have been because I cut out parts of our result section from the full report to make the EA Forum post shorter, but we discuss that the top part is cross-sectional as you say, and the bottom panel of Figure 4 (with difference scores) is more causal evidence.

Thanks. I think the issue is the use of the word effect, which usually implies causality in my field (Economics), rather than association when referring to the cross-sectional analysis alongside the fact that context was lost when it was edited down for the forum.

Small relevant bump that if anyone is interested in hearing more about this work, we're actually organising a webinar about it! It'll be on Monday 5th of June, 6-7pm BST and you can sign up here.

I find the discussion of these claims interesting. I would also warn about extrapolating this to any other issue. Climate issues are well supported over there. But this doesn't mean the same would be true for issues with minority support. Just in my field, I've seen a minority of animal advocates poison the word "vegan" in the United States, as I document in Losing My Religions.

This is a very interesting study and analysis.

I was wondering what its implication would be for an area like animal rights/welfare where the baseline support is likely to be considerably lower than that of climate change.

If we assume that the polarization effect of radical activism holds true across other issues as well, then the fraction of people who become less supportive may be higher than those who have been persuaded to become more concerned (for the simple reason that to start with the the odds of people supporting even the more moderate animal rights positions would be rather low) .

I reckon though that such simple extrapolation is fraught and there are other factors that will come into the picture when it comes to animal advocacy.

This is a very interesting study and analysis!

I was wondering what its implication would be for an area like animal rights/welfare where the baseline support is likely to be considerably lower than that of climate change.

If we assume that the polarization effect of radical activism holds true across other issues as well, then the fraction of people who become less supportive may be higher than those who have been persuaded to become more concerned (for the simple reason that to start with the the odds of people supporting even the more moderate animal rights positions would be rather low) .

I reckon though that such simple extrapolation is fraught and there are other factors that will come into the picture when it comes to animal advocacy.

I'm really uncomfortable with this post. It implicitly supports immoral ends justifying the means actions (trapping people in their cars) if the result is good.

Seems like you can treat it as two separate questions, this post only tackling the first:

I agree with you it's a hard "no" on the second question, but the first question is still interesting to explore.