Introduction

The Maternal Health Initiative (MHI) works in northern Ghana delivering a light-touch training programme for midwives and nurses. Our training integrates contraceptive counselling into routine care to increase informed choice and uptake of family planning methods. We deliver this work in partnership with two local NGOs and the Ghana Health Service, and launched through the 2022 Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Programme.

This post was written by Sarah Eustis-Guthrie and Ben Williamson, MHI’s co-founders. It is split into two parts:

- A review of MHI’s first year of operation - what we’ve done; the impact we’ve had; our plans for 2024

- An overview of the marginal value of funding MHI - the funding needs for an organisation like MHI; the funding landscape for post-seed organisations; why we think donating to MHI is a particularly good bet (and why it might not be).

Part 1: MHI’s First Year in Review

TL;DR

In our first year, we…

- Developed and tested two evidence-based models of care with an estimated cost-effectiveness of $100/DALY on health effects alone, competitive with GiveWell’s top charities

- Trained providers at 18 facilities across 2 regions of Ghana, reaching an estimated 40,000 women over the next year

- Conducted in-depth on-the-ground research, surveying 836 women and 148 providers & facility directors

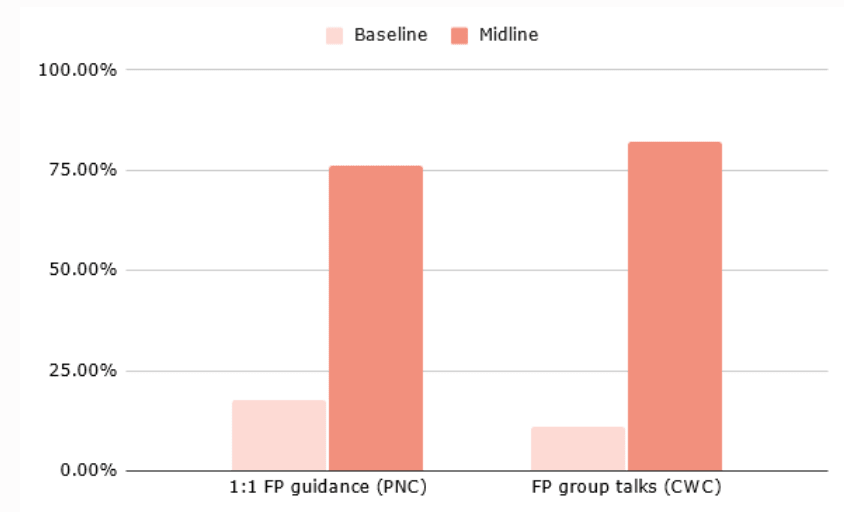

- Successfully increased the frequency of 1:1 family planning counselling by 4.3x at postnatal care and group family planning messaging by 8x at immunisation sessions, with results for shifts in contraceptive uptake due in December 2023.

We’re currently awaiting the full results from our pilot. With strong results, we plan to scale our work through 2024 in partnership with the Ghana Health Service as we build towards government adoption of our model of care.

Who are MHI?

Maternal Health Initiative is an early-stage global health charity with a focus on healthcare worker training and access to family planning. MHI was born out of research conducted by Charity Entrepreneurship identifying postpartum (post-birth) family planning as among the most cost-effective and evidence-based approaches for improving global health.

Our team now includes Sofia Martinez Galvez as our Program Officer, Sulemana Hikimatu Tibangtaba as our Training Facilitator, and Enoch Weyori and Racheal Antwi as Project Officers through our local implementing partners, Norsaac and Savana Signatures.

What we do

We train midwives and nurses in the integration of two new models of family planning counselling developed by MHI into the standard check-ups mothers and their children receive in the months after giving birth.

In doing so, our work increases postpartum contraceptive uptake and decreases the frequency of short-spaced births. Pregnancies that occur less than two years apart are associated with a 32% higher rate of maternal mortality and 18% higher rate of infant mortality (Conde-Agudelo 2007; Kozuki 2013). Despite these risks, contraceptive use drops by two-thirds in the early postpartum period.

Integrating high-quality counselling into routine care addresses multiple barriers to contraceptive uptake. First, mothers do not need to travel to a facility specifically for family planning. This means that they can receive confidential information and that they are spared the costs - both in time and money - of a separate visit.

Second, many women express significant concerns around side effects and health consequences from family planning. High-quality counselling ensures women receive counselling on multiple methods - helping to find a method that avoids the side effects they may be concerned about - while addressing the myths and misconceptions that can drive opposition to the use of methods.

Why Ghana?

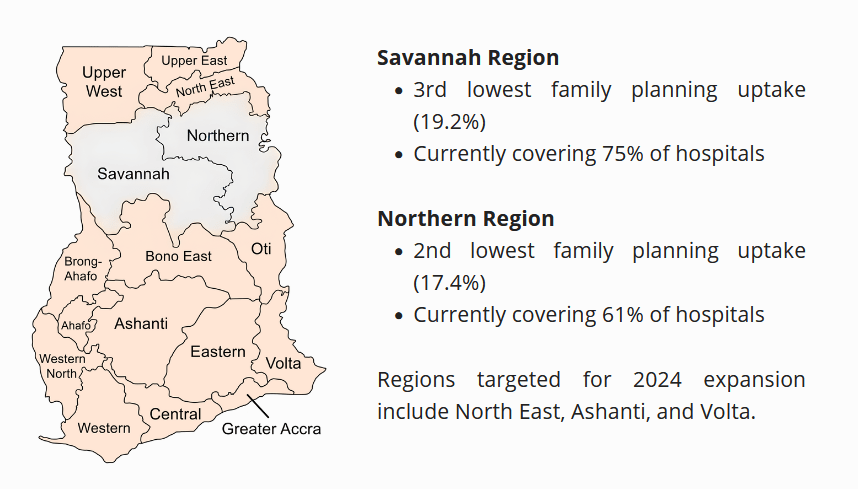

One of our first decisions was choosing which country to operate in. We conducted field visits to Sierra Leone and Ghana in January 2023 after an extensive process of research, data evaluation, and expert engagement identified these as the best choices out of 44 countries considered.

Statistically, Ghana has a high unmet need for family planning and significant maternal and infant mortality, while having one of the highest levels of facility delivery and most robust governance structures in sub-Saharan Africa. Government integration provides a route to potentially transformative cost-effectiveness at scale, making the last two factors - level of facility delivery and governance quality - particularly crucial to our work.

Models of Care

Our work is built around two models of care (programme arms), targeting different points in the continuum of care after delivery. Each programme is built directly off an RCT of a similar model (Asah-Opoku et al., 2023; Dulli et al., 2016), with a large body of evidence demonstrating the impact of postpartum family planning more broadly.

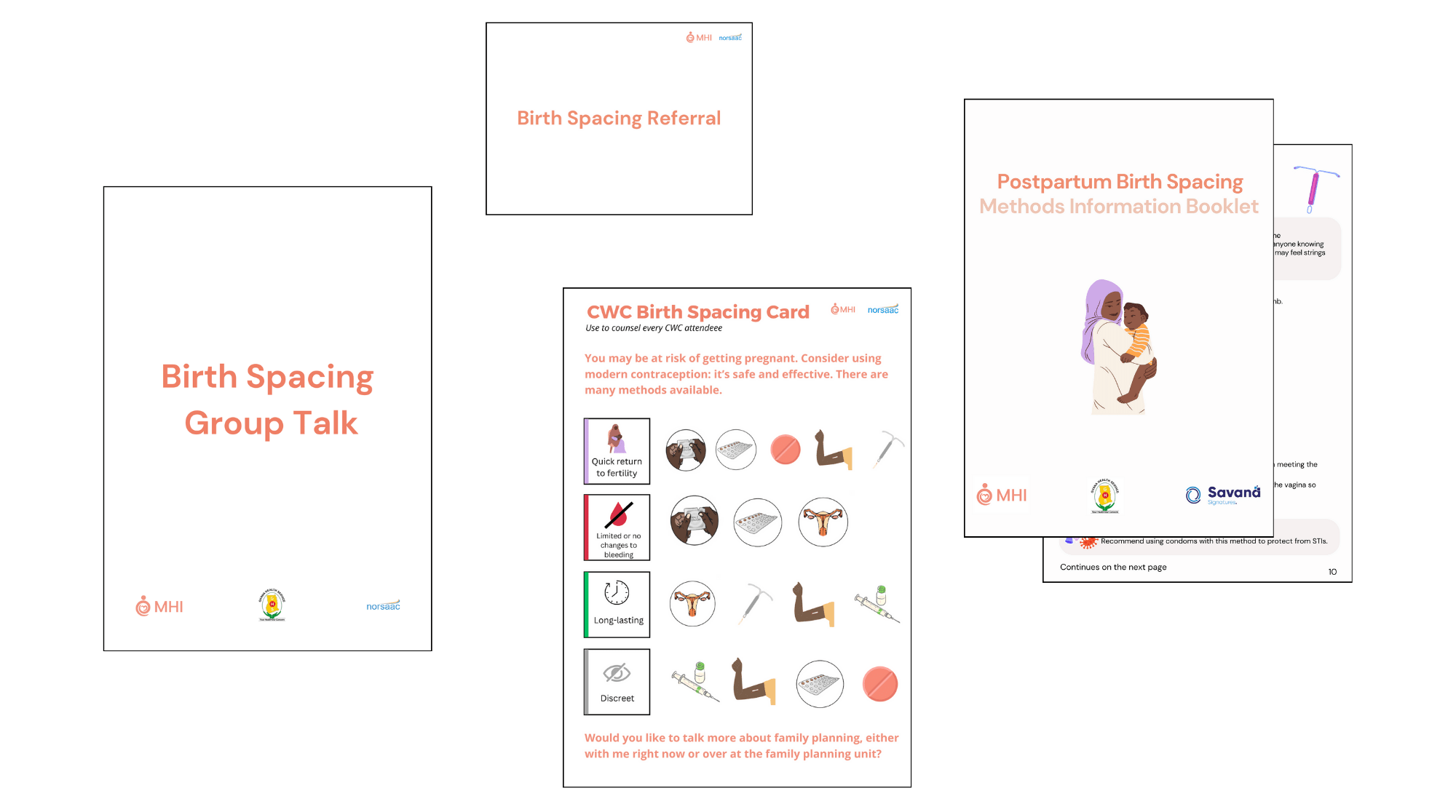

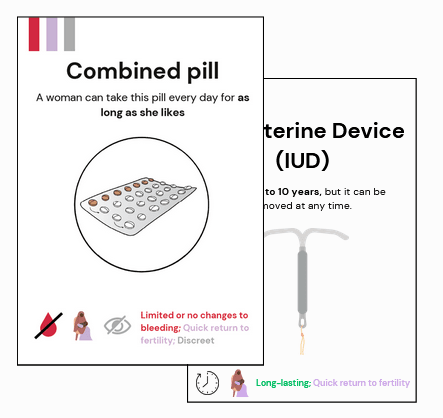

The postnatal care (PNC) arm integrates 10-15 minute family planning counselling into existing individual one-on-one appointments that take place 48 hours, 2 weeks, and 6 weeks post-birth. We developed a conversation guide and method cards to facilitate sessions and emphasise the delivery of client-centred care.

The child welfare clinic (CWC) arm targets the monthly sessions mothers attend from six weeks onwards with a primary focus on their child’s health and wellbeing. Our programming adds a group talk on family planning as well as brief, 1:1 counselling on family planning during vaccination into these sessions. We developed a flipchart for the group talk, as well as a card for very brief discussion during the 1:1 engagement.

For both of our programme arms, we have carefully designed materials that are specially tailored to the point of care and needs of the women we serve. Hospitals can be understaffed with providers overstretched, making it crucial to design improvements to care that are feasible and easy for providers to use. We have received consistently positive feedback from providers on the practicality of our tools.

Programme Delivery

This year, MHI ran three major projects covering 18 facilities across two regions of Ghana. In total, we estimate around 40,000 women will receive MHI’s model of counselling through these projects.

Proof of Concept

In April 2023, we ran our first two training sessions at the conclusion of an extensive process of qualitative research in which we interviewed 151 clients and providers.

One key aim was to understand the feasibility of delivering single-day training sessions. Most other family planning training interventions we researched involved multi-day or even multi-week trainings. One-day trainings placed significant time constraints on our programme delivery with obvious and significant cost-saving benefits.

Data from two of the six facilities[1] indicated a 15% increase in contraceptive uptake in the three months after the training sessions. This gave us confidence in the feasibility of our training delivery, while feedback from the providers and our partners helped us refine our programming models.

Mini-pilot

We launched a ‘mini-pilot’ in July 2023, training 45 providers from hospitals across two regions. Ahead of these trainings, we shifted to the two models of care described above, more specifically tailoring the training and materials we provide to the points of care at which they will be used.

These training sessions focused on refining the materials and ensuring consistent implementation of the models of care. One-month follow-up data from this project indicates a 4.3x increase in 1:1 counselling at postnatal care and an 8x increase in group counselling at immunisation sessions.

Pilot

These trainings took place in October 2023 after ethical approval from the Navrongo Health Research Centre. We trained 50 providers from six hospitals in the Northern Region which receive an estimated 20,000 clients annually.

We are currently conducting a six-week follow-up at these facilities to measure contraceptive uptake as a result of the intervention, through both in-person and phone surveying. These results will form the basis of MHI’s 2024 programming decisions and further engagement with the Ghana Health Service on next steps towards national programme adoption.

Our Impact

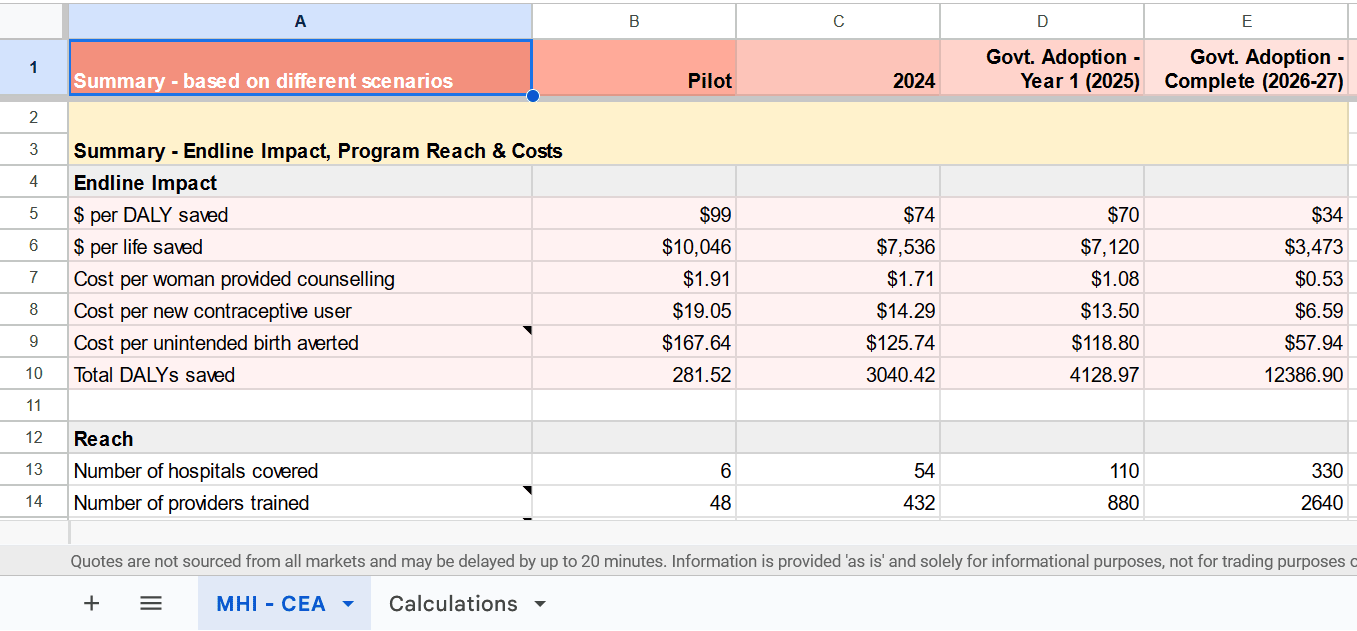

Estimating the impact of behaviour change interventions is tricky, especially for earlier-stage programmes for which long-run data comparisons and evaluations are not possible. We estimate that our pilot programme will avert a disability-adjusted life year (DALY) for just under $100, competitive with the cost-effectiveness of GiveWell top charities such as AMF. If we are successful in achieving government adoption of the programme, we estimate the cost per DALY would drop to just $34 while reaching around 800,000 mothers annually.

Beyond this, we firmly believe in the value of the non-health benefits of family planning access. Control over whether and when to have children is a fundamental marker of personal autonomy. There are robust arguments in favour of a much broader view of doing good, with prioritisation on the basis of subjective wellbeing or the capability approach providing two examples.

Discussing the merits of these is far beyond the scope of this post, but we believe the fundamental influence child-bearing has on people’s lives makes providing high-quality counselling for less than $2 per person highly valuable beyond its direct health implications.

Our Plans for 2024 (and beyond)

As mentioned above, we will have the results of our pilot programme in December 2023, including its impact on contraceptive uptake (the rate of contraceptive use). We have mapped out three scenarios for our 2024 work based on the success of the pilot and on the level of funding we raise in the coming months.

If the results of our pilot are strong, we plan to design a final large-scale evaluation of the most promising programming model (PNC or CWC) in partnership with the Ghana Health Service. This would be explicitly designed to model a fully-integrated model of the programme that the government would be open to adopting as part of the Ghana Health Service’s systems and policy should it prove successful.

With weaker results, we will focus on a smaller test of a redesigned model of care, dedicating more resources to testing potentially transformative changes to the delivery of our work, such as a Whatsapp-driven model of training delivery, that could make direct programme delivery exceptionally cost-effective in its own right.

Part 2: Marginal Funding

Moving beyond the work we’ve done, we’d like to discuss in more detail the value of a marginal grant to MHI as part of the Marginal Funding Week.

What we’re looking to fundraise

MHI received generous seed funding out of the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Programme that has allowed us to focus on the development and implementation of our programming over actively fundraising in our first year. As we wrap up our pilot over the next few weeks, we’re switching our attention to fundraising.

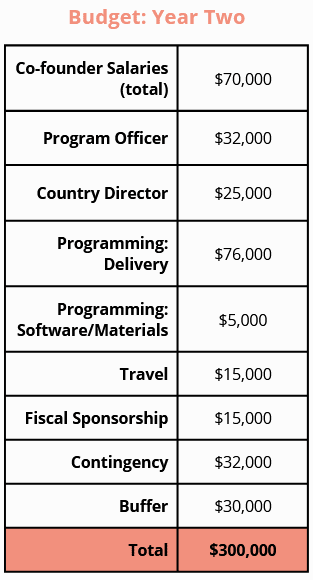

In an ideal world, we’d have around $300,000 to spend between now and the end of 2024. At a minimum, we’re looking to raise $100,000 as a funding bridge into the middle of 2024. Without this, we will have to delay hiring a Country Director, a critical position providing the advocacy experience and relationships we need as we look to design our next phase of work in tight collaboration with the Ghana Health Service.

$300,000 would cover the scale-up of our best programme to around 50 hospitals across three regions, likely reaching more than 100,000 women with our counselling. A rigorous assessment of this work, designed in close partnership with the Ghana Health Service at each step, is the evidence we need to secure an initial commitment to government adoption of MHI’s changes to care.

Marginal Value & the Valley of Death

At the most fundamental level, a donation to MHI helps keep an early-stage organisation alive where otherwise we might be forced to cease operations. MHI’s current runway can carry us through to March-June 2024, depending on spending rates.

Delivering programming on the ground is time-intensive, particularly in the early stages as you develop and then continually refine the systems needed to deliver an intervention.

MHI - as an organisation more than a year old with an established programming presence but without a tailored RCT or major donor backing our work - sits awkwardly between seed funding and institutional donors. This awkward position is often referred to as ‘the valley of death’ in which costs have significantly increased yet funding opportunities have diminished.

Programmes like D-Prize explicitly target new ventures, while major institutions such as GiveWell or the Gates Foundation tend to focus their resources on larger organisations with the capacity to absorb several hundred thousand dollars a year in funding at a minimum.

As many more organisations are founded through programmes like D-Prize and Charity Entrepreneurship, the need and competition for post-seed funding is likely to significantly increase.

So what are the solutions? Government-driven funding for global health and development programmes from bodies like USAID and Grand Challenges Canada can fill some of the gap. However, accessing this funding is far from guaranteed with time-consuming application processes that can be opaque in their evaluation.

What makes EA donors special

If MHI can get government grants and money from private foundations, why fundraise from EA donors? A few reasons:

- Government and foundation grants are slow.

It can easily take more than six months from application submission to the receipt of funds from organisations like USAID or Grand Challenges. In comparison, a private donor's money can reach us today. Our aim is to progress towards near-complete funding from governments and foundations within the next two years, particularly given the potential counterfactual benefits of non-EA funding. But we’re not there yet. While we have begun multiple applications with these types of funders, we would likely have to downsize or at least delay key parts of our work to stretch our current funding to the likely receipt of funds from these sources.

- Government and foundation applications and compliance are time-consuming.

The application process for many grants, combined with ongoing compliance and due diligence, can require a dedicated part-time staff member on their own. A recent application to Grand Challenges Canada took about two weeks’ worth of full-time staff hours. These grants are also often aimed at organisations with a larger reach and longer track record than an organisation like MHI.

- EA donations are unrestricted.

Unrestricted donations provide vital programming flexibility when unexpected costs occur or opportunities arise. This has been key to meeting ambitious programme development targets, allowing us to use external contractors at pinch points in programme design and deliver cash advances to our partners to cover last-minute costs that prevent major issues in training delivery. The trust EA donors place in organisations like ours is the primary reason most EA organisations do not require the kind of dedicated fundraising team seen at many other charities.

Funding scenarios (what your money would buy)

$50 - Pays for the stipend to a programme champion for three months, our eyes and ears at the facility ensuring care is consistently delivered as designed. The average hospital we work in will reach around 800 clients during this time, with a 1% shift in contraceptive uptake through more universal programme implementation reducing our cost per DALY by around 15% (from $99 to $86 per DALY for our pilot).

$500 - Covers the printing and distribution of all programming materials to six hospitals as part of our training. Counselling guides, referral guides, family planning information books, and individual method cards all included. These materials would be used to counsel an estimated 18,000 clients annually across the six facilities.

$5,000 - Funds the entire cost of our monitoring and evaluation work around a project the size of our pilot. This includes a surveying team visiting each of the facilities to collect baseline, midline, and endline results, as well as separate phone surveying, coordination with the Regional Health Directorates, and filing for ethical approval.

$50,000 - Likely covers the full costs of MHI’s planned hiring next year (based on our current runway) as we look to scale our programming, funding both a Programme Officer and Country Director to work full-time for MHI through 2024. A Country Director who can leverage existing relationships with key stakeholders and interact with the government day-to-day greatly increases the likelihood of successful government adoption of MHI’s programme beyond 2024.

Reasons to fund MHI (why we think our work is a very good bet)

Cost-effectiveness - we estimate our pilot will cost $99 per DALY averted. This could be a conservative estimate given the contraceptive uptake modelled for the pilot (10%) is significantly lower than that measured for the Proof of Concept (15%).

Government partnership & adoption - MHI’s approach is specifically geared towards long-term adoption of the programme by the Ghanaian government. While our current modelling anticipates decaying benefits from counselling over the course of a year, successful adoption and government ownership of the programme would likely produce impact over several years for minimal additional cost.

Valuing more than health effects - MHI’s programming appears cost-competitive with some of GiveWell’s top charities on health effects alone. We believe that there are fundamental additional benefits to autonomy and subjective wellbeing from providing mothers with informed choice around both when and whether to have children.

Building an EA presence in a new country - MHI has built relationships and connections from scratch in Ghana, paving the way for other high-impact organisations to fast-track the implementation of programming in West Africa’s second-largest country.

Reasons not to fund MHI (uncertainties)

Uncertainty over impact - MHI’s pilot results measuring the impact of our work on contraceptive uptake are not yet available, with surveying due to conclude at the beginning of December. As such, our cost-effectiveness numbers remain projections. However, it is worth noting that the stronger evidence for our programme’s effectiveness comes from its basis in RCTs conducted by other actors - pilot results for any programme have significant uncertainties and error bars.

Scepticism around government adoption - as emphasised throughout this article, MHI’s long-term aim is for government adoption of the changes to routine care that we are trialling through our programming. Government advocacy, adoption, and successful long-term delivery are all challenging. Should MHI ultimately fail to achieve full government adoption, we think direct implementation could still be highly cost-effective (particularly if we are successful in shifting our funding sources at scale).

Population ethics - We acknowledge that certain philosophical frameworks that prioritise utility maximisation may disagree with the impactfulness of family planning work. While we personally do not find these views convincing, we appreciate that people may hold differing philosophical perspectives in good faith.

How to support us

Donate

If you would like to support our work, you can donate directly through our website. Donations are fully tax-deductible for US tax residents. For larger donations, we’d love to speak to you personally to answer any questions you may have about our work - please reach out at sarah@maternalhealthinitiative.org.

Recommend to a friend

If you know someone who might be interested in supporting our work, we’d love you to recommend us to them - by sharing this article, by linking to our website, or encouraging them to join our newsletter.

Follow our work

If you’d like to stay in touch with our work, we’d love to keep you informed. Follow us on LinkedIn, Facebook, or subscribe to our newsletter.

Thanks for reading! If you have questions about our work, or would like more information about marginal funding for an organisation of our size/position, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to reply where we can.

- ^

Data from other facilities was not reported by the Ghana Health Service

I want to highlight that I think MHI's explicit aim for this model to be adopted by the government is a great response to the criticisms of aid where there are concerns about dependency, and criticisms of the NGO sector where there are concerns about short-termism and displacing the government and public services.

I think other global health charities should consider a similar approach, where an intervention is demonstrated to be highly cost-effective, and this is used to encourage the government to scale this up and integrate it into public services, rather than having the charity scale it up independently.

The problem with "get governments to scale up and integrate" is that governments... suck. Corruption, incompetence, straight up theft, etc. mean that these interventions which were being provided, when taken over by the government just disappear in a few years.

Many people in the West feel that governments are maybe a bit wasteful and inefficient but on the whole good/okay. In developing countries, this is not always the case.

Also, as Karen Levy pointed out in her ep on the 80k podcast, adoption by LMIC governments effectively means the taxpayers of these countries are the ones to pay. Sustained service by an internationally funded charity represents a desirable wealth transfer to LMICs. Better than the charity graduating from being funded by EAs to being funded by LMIC governments would be for it to graduate to being funded by big funders with cheap counterfactuals like USAID.

(To play devil’s advocate to myself: If government adoption means capacity building in LMIC healthcare systems then that’s great compared to dependence on sustained service from international NGOs. Maybe the best of both worlds is government adoption with ongoing technical assistance and international funding?)

I definitely agree with and share the concerns over government adoption as a silver bullet of sorts on the charity's side. Outsourcing all the costs when the government's money and resources are more counterfactually precious than the charity's is not the way we want things to go!

Our aim is closer to your last sentence: government adoption to leverage the cost-savings from delivery through their existing systems of training/data collection/material distribution, with MHI continuing to pay for the costs involved that the government wouldn't incur anyway.

I don't think adoption by LMIC governments removes the desirable wealth transfer to LMICs. I think most of the wealth transfers to LMICs will continue via other NGOs.

CGD have some interesting work making the case that governments should focus on prioritising the most cost-effective health services, and donors, whose funding is less reliable should focus on additional, less cost-effective stuff - https://www.cgdev.org/blog/putting-aid-its-place-new-compact-financing-health-services

Executive summary: The Maternal Health Initiative trains healthcare providers in Ghana to integrate family planning counselling into routine postnatal care. In their first year, they reached 18 facilities and estimate averting disability-adjusted life years for $99 each. Their goal is government adoption of their model to reach 800,000 mothers annually at just $34 per DALY.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.