Introduction

First they came for the epistemology/we don’t know what happened after that.

I’m fairly antagonistic towards the author of that tweet, but it still resonates deep in my soul. Anything I want to do, anything I want to change, rests on having contact with reality. If I don’t have enough, I might as well be pushing buttons at random.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of forces pushing against having enough contact with reality. It’s a lot of work even when reality cooperates, many situations are adversarial, and even when they’re not entropy itself will constantly chip away at your knowledge base.

This is why I think constantly seeking contact with reality is the meta principle without which all (consequentialist) principles are meaningless. If you aren’t actively pursuing truthseeking, you won’t have enough contact with reality to make having goals a reasonable concept, much less achieving them. To me this feels intuitive, like saying air is necessary to live. But I’ve talked to many people who disagree, or who agree in the abstract but prioritize differently in the breach. This was supposed to be a grand post explaining that belief. In practice it’s mostly a bunch of pointers to facets of truthseeking and ideas for how to do better. My hope is that people can work backwards from these to the underlying principle, or flesh out their own relationship with truthseeking.

Target audience

I think these are good principles for almost any situation, but this essay is aimed at people within Effective Altruism. Most of the examples are from within EA and assume a certain amount of context. I definitely don’t give enough information to bring someone unfamiliar up to speed. I also assume at least a little consequentialism.

A note on examples and actions

I’m going to give lots of examples in this post. I think they make it easier to understand my point and to act on what agreement you have. It avoids the failure mode Scott Alexander discusses here, of getting everyone to agree with you by putting nothing at stake.

The downside of this is that it puts things at stake. I give at least 20 examples here, usually in less than a paragraph, using only publicly available information. That’s enough to guarantee that every person who reads this will find at least one example where I’m being really unfair or missing crucial information. I welcome corrections and arguments on anything I say here, but when evaluating the piece as a whole I ask that you consider the constraints I was working under.

Examples involving public writing are overrepresented. I wanted my examples to be as accessible as possible, and it’s hard to beat public writing for that. It even allows skimming. My hope is that readers will work backwards from the public examples to the core principle, which they can apply wherever is most important to them.

The same goes for the suggestions I give on how to pursue truthseeking. I don’t know your situation and don’t want to pretend I do. The suggestions are also biased towards writing, because I do that a lot.

I sent a draft of this post to every person or org with a negative mention, and most positive mentions.

Facets of truthseeking

No gods, no monsters, no epistemic daddies

When I joined EA I felt filled with clarity and purpose, at a level I hadn’t felt since I got rejected from grad school. A year later I learned about a promising-looking organization outside EA, and I felt angry. My beautiful clarity was broken and I had to go back to thinking. Not just regular thinking either (which I’d never stopped doing), but meta thinking about how to navigate multiple sources of information on the same topic.

For bonus points, the organization in question was J-PAL. I don’t know what the relationship was at the time, but at this point GiveWell uses their data, and both GiveWell and OpenPhil give them money. So J-PAL was completely compatible with my EA beliefs. I just didn’t like the idea that there might be other good sources I’d benefit from considering.

I feel extra dumb about this because I came to EA through developmental economics, so the existence of alternate sources was something I had to actively forget.

Other people have talked about this phenomenon from various angles, but it all feels tepid to me. Qiaochu Yuan’s thread on the search for epistemic daddies has some serious issues, but tepidness is not one of them.

Reading this makes me angry because of the things he so confidently gets wrong (always fun to have a dude clearly describe a phenomenon he is clearly experiencing as “mostly female”). But his wild swings enable him to cut deeper, in ways more polite descriptions can’t. And one of those deep cuts is that sometimes humans don’t just want sources of information to improve their own decision making, they want a grown-up to tell them what is right and when they’ve achieved it.

I won’t be giving examples for this facet beyond past-me and Qiaochu. I don’t feel good singling anyone else out as a negative example, and positive examples are called “just being normal”, which most people manage most of the time.

Actions

Delegate opinions instead of deferring

There is nothing wrong with outsourcing your judgment to someone with better judgment or more time. There are too many things you need to do to have contact with all of reality. I’d pay less for better car maintenance if I understood cars better. When I buy a laptop I give some goals to my friend who’s really into laptop design and he tells me what to buy and when, because he’s tracking when top manufacturers are changing chips and the chips’ relative performance and historical sales discounts and… That frees up time for me to do lit reviews other people can use to make better decisions themselves. And then my readers spend their newfound energy on, I don’t know, hopefully something good. It’s the circle of life.

But delegating your opinion is a skill. Some especially important aspects of that skill are:

- Be aware that you’re delegating, instead of pretending you came to the conclusion independently.

- Make that clear to others as well, to avoid incepting a consensus of an idea no one actually believes.

- Track who you’re delegating to, so you can notice if they change their opinion.

- The unit of deference is “a person, in a topic, while I’m no more than X surprised, and the importance is less than Y”

- I was very disappointed to learn people can be geniuses in one domain and raving idiots in another. Even within their domain they will get a few things critically wrong. So you need to be prepared to check their work when it’s particularly surprising or important.

- Keep track of how delegating to them works out or doesn’t, so you’re responding to their actual knowledge level and not the tone of their voice.

- Separate their factual judgment from emotional rewards for trusting them.

- Have multiple people you delegate to in a given area, especially if it’s important. This will catch gaps early.

- The person ultimately in control of your decisions is you. You can use other people’s opinions to influence your decisions to the exact degree you think is wise, but there is no escaping your responsibility for your own choices.

Stick to projects small enough for you to comprehend them

EA makes a very big push for working on The Most Important Problem. There are good reasons for that, but it comes at a high cost.

If you have your own model of why a problem is Most Important, you maintain the capability to update when you get new information. As you defer, you lose the ability to do that. How are you supposed to know what would change the mind of the leader you imprinted on? Maybe he already had this information. Maybe it’s not a crux. Or maybe this is a huge deal and he’d do a 180 if only he heard this. In the worst cases you end up stuck with no ability to update, or constantly updating to whichever opinion you last heard with a confident vibe.

You will also learn less pursuing projects when you’re deferring, for much the same reason. You’ve already broken the feedback loop from your own judgment, so how do you notice when things have gone too off track?

There are times this sacrifice is worth it. If you trust someone enough, track which parts of your model you are delegating, or pick a project in a settled enough area, you can save a lot of time not working everything out yourself. But don’t assume you’re in that situation without checking, and be alert to times you are wrong.

Seek and create information

I feel like everyone is pretty sold on this in the abstract, so I won’t belabor the point. I don’t even have real suggestions for actions to accomplish this, more categories of actions. But I couldn’t really make a whole essay on truthseeking without mentioning this.

Shout out to GiveDirectly, whose blog is full of posts on experiments they have run or are running. They also coordinate with academics to produce papers in academic journals. Points for both knowledge creation and knowledge sharing.

Additional shoutout to Anima International. AI used to have a campaign to end home carp slaughter in Poland. They don’t any more, because their research showed people replaced carp with higher-accumulated-suffering fish. I would take off points for the formal research being sparked by a chance news story rather than deliberate investigation, but I’d just have to give them back for the honest disclosure of that fact.

Actions

The world is very big and you can’t know everything. But if you’re not doing some deep reading every year, I question if EA is for you. For bonus points you can publicly share your questions and findings, which counts as contributing to the epistemic commons.

Make your feedback loops as short as possible (but no shorter).

I argued with every chapter of the Lean Start-Up book but damned if I didn’t think more experimentally and frontload failure points more after I finished it. This despite already knowing and agreeing with the core idea. The vibes are top notch.

Protect the epistemic commons

Some things are overtly anti-truthseeking. For example, lying.

But I don’t think that’s where most distortions come from, especially within EA. Mustache-twirling epistemic villains are rare. Far more common are people who know something and bias their own perception of reality, which they pass on to you.

E.g. a doctor knows his cancer drug works, and is distraught at the thought of people who will suffer if the FDA refuses to approve it. He’d never falsify data, but he might round down side effects and round up improvements in his mind. Or that doctor might have perfect epistemic virtue, but fails to convey this to his assistants, who perform those subtle shifts. He will end up even more convinced of his drugs’ impact because he doesn’t know the data has been altered.

If the doctor was deliberately lying while tracking the truth, he might discover the drug’s cost benefit ratio is too strong for even his tastes. But if he’s subtly and subconsciously suppressing information he won’t find out unless things go catastrophically wrong. At best the FDA will catch it after some number of unnecessary deaths, but if it’s subtle the falsehood may propagate indefinitely.

Or they might put up subtle barriers to others’ truthseeking. There are too many methods to possibly list here, so let’s talk about the one that most annoys me personally: citing works you will neither defend, nor change your views if they are discovered to be fundamentally flawed, but instead point to a new equally flawed source that supports your desired conclusion. This misleads readers who don’t check every source and is a huge time cost for readers who do.

Actions

Care less about intent and more about whether something brings you more or less contact with reality.

Some topics are inherently emotional and it’s anti-truthseeking to downplay that. But it’s also anti-epistemic to deliberately push others into a highly activated states that make it harder for them to think. This is one reason I hate the drowning child parable.

If you see something, say something. Or ask something. It’s easy to skip over posts you see substantial flaws in, and pushing back sometimes generates conflict that gets dismissed as drama. But as I talk more about in “Open sharing of information”, pushing back against truth-inhibiting behavior is a public service.

Sometimes saying something comes at great personal risk. One response to this is to do it anyway, whatever the cost. This is admirable (Nikolai Vavilov is my hero), but not something you can run a society on. The easier thing to do is get yourself in a position of lower risk. Build a savings cushion so you can afford to get fired. Hang out with friends that appreciate honesty even when it hurts. This lets you save the bravery for when nothing else can substitute.

Managers, you can help with the above by paying well, and by committing to generous severance no matter what terms the employee leaves on.

As a personal favor to me, only cite sources you actually believe in. They don’t have to be perfect, and it’s fine to not dump your entire evidence base in one post. All you have to do is disclose important flaws of your sources ahead of time, so people can make an accurate assessment. Or if it’s too much work to cite good sources, do even less work by explicitly noting your claim as an assumption you won’t be trying to prove. Those are both fine! We can’t possibly cite only perfect works, or prove an airtight case for everything we say. All I ask is that you don’t waste readers’ time with bad citations.

Sometimes it’s impossible to tell whether an individual statement is truthseeking. It’s a real public service to collect someone’s contradictory statements in public so people can see the bigger picture with less work. Ozzie Gooen’s recent post on Sam Altman and OpenAI is a good example. It would be better with sources, but not so much better I’d want to delay publication.

In most cases it’s anti-epistemic to argue with a post you haven’t read thoroughly. OTOH, some of the worst work protects itself by being too hard to follow. Sometimes you can work around this by asking questions.

You can also help by rewarding or supporting someone else’s efforts in truthseeking. This could be money, but there are very few shovel ready projects (I’ve offered Ozzie money to hire a contractor to find evidence for that post, although TBD if that works out). OTOH, there is an endless supply of epistemically virtuous posts that don’t get enough positive attention. Telling people you like their epistemic work is cheap to provide and often very valuable to them (I vastly prefer specifics over generalities, but I can’t speak for other people).

Contact with reality should (mostly) feel good

Some of the most truthseeking people I know are start-up founders asking for my opinion on their product. These people are absolutely hungry for complaints, they will push me to complain harder and soften less because politeness is slowing me down. The primary reason they act like this is because they have some goal they care about more than the social game. But it doesn’t hurt that it’s in private, they get a ton of social approval for acting like this, and the very act of asking for harsh criticism blunts the usual social implications of hearing it.

I think it’s fine not to act like this at all times in every area of your life- I certainly don’t. But it’s critical to notice when you are prioritizing social affirmation and accept what it implies about the importance of your nominal goal. If you object to that implication, if you think the goal is more important than social standing, that’s when you need to do the work to view criticism as a favor.

Actions

“Cultivate a love of the merely real” is not exactly an action but I can’t recommend it enough.

Sometimes people have trauma from being in anti-truthseeking environments and carry over behaviors that no longer serve them. Solving trauma is beyond the scope of this post, but I’ll note I have seen people improve their epistemics as they resolved trauma so include that in your calculations.

There are lots of ways to waste time on forecasting and bets. On the other hand, when I’m being properly strategic I feel happy when I lose a bet. It brings a sharp clarity I rarely get in my life. It reminds me of a wrong belief I made months ago and prompts me to reconsider the underlying models that generated it. In general I feel a lot of promise around forecasting but find it pretty costly; I look forward to improved knowledge tech that makes it easier.

I found the book Crucial Conversations life altering. It teaches the skills to emotionally regulate yourself, learn from people who are highly activated, make people feel heard so they calm down, and share your own views without activating them. Unlike NVC it’s focused entirely on your own actions.

Open sharing of information

This has multiple facets: putting in the work to share benign information, sharing negative information about oneself, and sharing negative information about others. These have high overlap but different kinds of costs.

The trait all three share is that the benefits mostly accrue to other people

Even the safest post takes time to write. Amy Labenz of CEA mentioned that posts like this one on EAG expenses take weeks to write, and given the low response her team is reducing investment in such posts. I’ll bet this 4-part series by Adam Zerner on his aborted start-up took even longer to write with less payoff for him.

Sharing negative information about yourself benefits others- either as by providing context to some other information, or because the information is in and of itself useful to other people. The downside is that people may overreact to the reveal, or react proportionately in ways you don’t like. Any retrospective is likely to include some of this (e.g. check out the comments on Adam’s), or at least open you up to the downsides.

For examples, see the Monday morning quarterbacking on Adam’s posts, picking on very normal founder issues, or my nutrition testing retrospective. The latter example was quite downvoted and yet a year later I still remember it (which is itself an example of admitting to flaws in public- I wish I was better at letting go. Whether or not it’s a virtue that I got angry on Adam’s behalf as well, when he wasn’t that bothered himself, is left as an exercise to the reader).

Publicly sharing information about others is prosocial because it gets the information to more people, and gives the target a clear opportunity to respond. But it rarely helps you much, and pisses the target off a lot. It may make other people more nervous being around you, even if they agree with you. E.g. an ingroup leader once told me that my post on MAPLE made them nervous around me. I can make a bunch of arguments why I think the danger to them was minimal, but the nervous system feels what it feels.

Criticizing others often involves exposing your own flaws. E.g. This post about shutting down the Lightcone co-working space, or Austin Chen’s post on leaving Manifold. Both discuss flaws in entities they helped create, which risks anger from the target and worsening their own reputation.

It is the nature of this facet that it is hard to give negative examples. But I think we can assume there are some departing OpenAI employees who would have said more, sooner if OpenAI hadn’t ransomed their equity.

Actions

Public retrospectives and write-ups

Spend a little more time writing up announcements, retrospectives, or questions from you or your org than feels justified. The impact might be bigger than you think, and not just for other people. Austin Chen of Manifund shared that his team often gets zero comments on a retrospective; and some time later a donor or job applicant cites it as the cause of their interest. Presumably more people find them valuable without telling Manifund.

Which brings up another way to help; express appreciation when people go through the work to share these write-ups. Ideally with specifics, not just vague gratitude. If a write-up ends up influencing you years later, let the author know. Speaking as an author who sometimes gets these, they mean the world to me.

Beware ratchet effects

Gretta is a grantmaker that works at Granty’s Grantmaking Foundation. She awards a grant to medium-size organization MSO.

Granty’s has some written policies, and Gretta has some guesses about the executives’ true preferences. She passes this on to fundraiser Fred at MSO. She’s worried about getting yelled at by her boss, so she applies a margin around their wishes for safety.

Fred passes on Gretta’s information to CEO Charlotte. Communication is imprecise, so he adds some additional restrictions for safety.

CEO Charlotte passes on this info to Manager Mike. She doesn’t need some middle manager ruining everything by saying something off-message in public, so she adds some additional restrictions for safety.

Manager Mike can tell Charlotte is nervous, so when he passes the rules down to his direct reports he adds on additional restrictions for safety.

By the time this reaches Employee Emma (or her contractor, Connor), so many safety margins have been applied that the rules have expanded beyond what anyone actually wanted.

New truths are weird

Weird means “sufficiently far from consensus descriptions of reality”. There’s no reason to believe we live in a time when consensus descriptions of reality are 100% accurate, and if you do believe that there’s no reason to be in a group that prides itself on doing things differently.

Moreover, even very good ideas in accord with consensus reality have very little alpha, because someone is already doing them to the limits of available tech. The actions with counterfactual impact are the ones people aren’t doing.

[You might argue that some intervention could be obvious when pointed out but no one has realized the power of the tech yet. I agree this is plausible, but in practice there are enough weirdos that these opportunities are taken before things get that far.]

Weirdness is hard to measure, and very sensitive to context. I think shrimp welfare started as a stunning example of openness to weirdness, but at this point it has (within EA) become something of a lapel pin. It signals that you are the kind of person who considers weird ideas, while not subjecting you to any of the risks of actually being weird because within EA that idea has been pretty normalized. This is the fate of all good weird ideas, and I congratulate them on the speedrun. If you would like to practice weirdness with this belief in particular, go outside the EA bubble.

On the negative side: I can make an argument for any given inclusion or exclusion on the 80,000 hours job board, but I’m certain the overall gestalt is too normal. When I look at the list, almost every entry is the kind of things that any liberal cultivator parent would be happy to be asked about at a dinner party. Almost all of the remaining (and most of the liberal-cultivator-approved) jobs are very core EA. I don’t know what jobs in particular are missing but I do not believe high impact jobs have this much overlap with liberal cultivator parent values.

To be clear, I’m using the abundance of positions at left-leaning institutions and near absence of conservative ones as an indicator that good roles are being left out. I would not be any happier if they had the reversed ratio of explicitly liberal to conservative roles, or if they had a 50:50 ratio of high status political roles without any weirdo low status ones.

High Decoupling, Yet High Contextualizing

High decoupling and high contextualizing/low decoupling have a few definitions, none of which I feel happy with. Instead I’m going to give four and a half definitions: caricatures of how each side views itself and the other. There’s an extra half because contextualizing can mean both “bringing in more information” and “caring more about the implications”, and I view those pretty differently.

High decoupling (as seen by HD): I investigate questions in relative isolation because it’s more efficient.

Contextualizing (as seen by C): The world is very complicated and more context makes information more useful and more accurate.

HD (as seen by C): I want to ignore any facts that might make me look bad or inhibit my goal.

C-for-facts (as seen by HD): I will drown you in details until it’s impossible to progress

C-for-implications (as seen by HD): you’re not allowed to notice or say true things unless I like the implications.

My synthesis: the amount of context to attach to a particular fact/question is going to be very dependent on the specific fact/question and the place it is being discussed. It’s almost impossible to make a general rule here. But “this would have bad implications” is not an argument against a fact or question. Sometimes the world has implications we don’t like. But I do think that if additional true context will reduce false implications, it’s good to provide that, and the amount that is proper to provide does scale with the badness of potential misinterpretations. But this can become an infinite demand and it’s bad to impede progress too much.

Hope that clears things up.

Actions

Get good.

Willing to hurt people’s feelings (but not more than necessary)

Sometimes reality contains facets people don’t like. They’ll get mad at you just for sharing inconvenient facts with them. This is especially likely if you’re taking some action based on your perception of reality that hurts them personally. But it’s often good to share the truth anyway (especially if they push the issue into the public sphere), because people might make bad decisions out of misplaced trust in your false statements.

For example, many years ago CEA had a grantmaking initiative (this was before EA Funds). A lot of people were rejected and were told it was due to insufficient funds not project quality. CEA was dismayed when fewer people applied the next round, when they hadn’t even met their spending goal the last round.

In contrast, I once got a rejection letter from Survival and Flourishing Fund that went out of its way to say “you are not in the top n% of applicants, so we will not be giving further feedback”. This was exactly the push I needed to give up on a project I now believe wasn’t worthwhile.

To give CEA some credit, Eli Nathan has gotten quite assertive at articulating EAG admissions policies. I originally intended to use that comment as a negative example due to inconsistent messaging about space constraints, but the rest of it is skillfully harsh.

My favorite example of maintaining epistemics in the face of sadness is over on LessWrong. An author wrote a post complaining about rate limits (his title refers to bans, but the post only talks about rate limits). Several people (including me) stepped up to explain why the rate limiting was beneficial, and didn’t shy away from calling it a quality issue. Some people gave specific reasons they disliked the work of specific rate-limited authors. Some people advocated for the general policy of walled gardens, even if it’s painful to be kept outside them. I expect some of this was painful to read, but I don’t feel like anyone added any meanness. Some writers put very little work into softening, but everything I remember was clear and focused on relevant issues, with no attacks on character.

Actions

Multiple friends have recommended The Courage To Be Disliked as a book that builds the obvious skill. I haven’t read it myself but it sure sounds like the kind of thing that would be helpful.

To the extent you want to resolve this by building the skill of sharing harsh news kindly, I again recommended Crucial Conversations.

Conclusion

Deliberately creating good things is dependent on sufficient contact with reality. Contact with reality must be actively cultivated. There are many ways to pursue this; the right ones will vary by person and circumstance. But if I could two epistemic laws, they would be:

- Trend towards more contact with reality, not less, however makes sense for you.

- Acknowledge when you’re locally not doing that.

Related Work

- Epistemic Legibility

- Butterfly Ideas

- EA Vegan Advocacy is not truthseeking, and it’s everyone’s problem

Thanks to: Alex Gray, Milan Griffes, David Powers, Raymond Arnold, Justin Devan, Daniel Filan, Isabel Juniewicz, Lincoln Quirk, Amy Labenz, Lightspeed Grants, every person I discussed this with, and every person and org that responded to my emails.

Thank you for this insightful post. While I resonate with the emphasis on the necessity of truthseeking, it's important to also highlight the positive aspects that often get overshadowed. Truthseeking is not only about exposing flaws and maintaining a critical perspective; it's also about fostering open-mindedness, generating new ideas, and empirically testing disagreements. These elements require significantly more effort and resources compared to criticism, which often leads to an oversupply of the latter and can stifle innovation if not balanced with constructive efforts.

Generating new ideas and empirically testing them involves substantial effort and investment, including developing hypotheses, designing experiments, and analyzing results. Despite these challenges, this expansive aspect of truthseeking is crucial for progress and understanding. Encouraging open-mindedness and fostering a culture of curiosity and innovation are essential. This aligns with your point about the importance of embracing unconventional, “weird” ideas, which often lie outside the consensus and require a willingness to explore and challenge the status quo.

Your post reflects a general EA attitude that emphasizes the negative aspects of epistemic virtue while often ignoring the positive. A holistic approach that includes both the critical and constructive dimensions of truthseeking can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of reality and drive meaningful progress. Balancing criticism with creativity and empirical testing, especially for unconventional ideas, can create a more dynamic and effective truthseeking community.

Something similar has been on my mind for the last few months. It's much easier to criticize than to do, and criticism gets more attention than praise. So criticism is oversupplied and good work is undersupplied. I tried to avoid that in this post by giving positive principles and positive examples, but sounds like it still felt too negative for you.

Given that, I'd like to invite you to be the change you wish to see in the world by elaborating on what you find positive and who is implementing it[1].

this goes for everyone- even if you agree with the entire post it's far from comprehensive

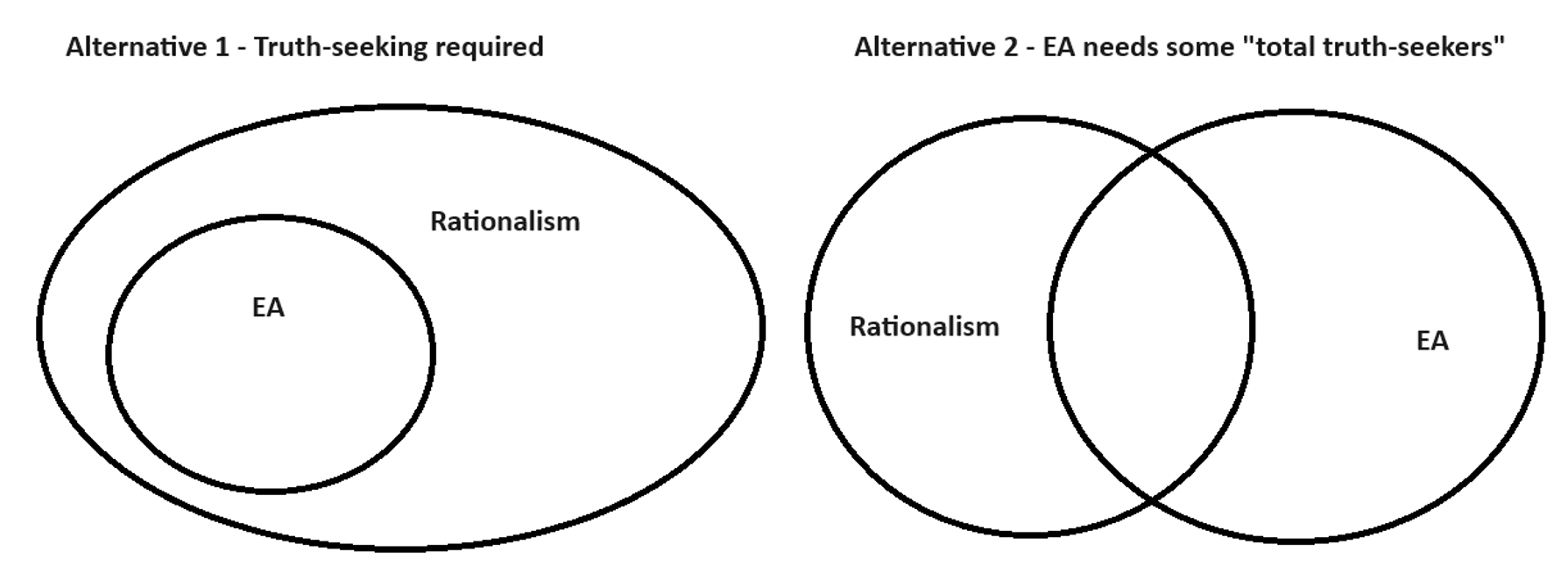

I generally really resonate with this piece. At the same time, when reading this, I keep wondering if this is advice perhaps more appropriate in LW/rationalist circles than in EA? In general, in EA, I do not clearly see why truth-seeking outside cause areas is super helpful? I actually see downsides with this as we can quickly descend into less action-relevant discussion e.g. around religion, gender/sexuality or even more hot-button topics (of course gender/sexuality is crucial in GH interventions centred on this topic!). I kind of feel truth seeking in such domains is perhaps net negative in EA, especially as we need to work across a range of cultures and with people from all walks of life. I think this is a difficult topic but wanted to mention it here as I could imagine some readers taking especially the heading on hurting other people's feelings as an encouragement in EA to say things that are mostly action irrelevant but gets them lots of attention. My current stance is to refrain from such truth-seeking in public until I have a very strong conviction it could actually change priorities and also have broad support in making public such potentially controversial takes.

I think you might be using "truth-seeking" a bit differently here from how I and others use it, which might be underlying the disagree-votes you're getting. In particular, I think you might be using "truth-seeking" to refer to an activity (engaging in a particular kind of discourse) rather than an attitude or value, whereas I think it's more typically used to refer to the latter.

I think it's very important to the EA endeavor to adopt a truth-seeking mindset about roughly everything, including (and in some cases especially) about hot-button political issues. At the same time, I think that it's often not helpful to try to hash out those issues out loud in EA spaces, unless they're directly relevant to cause prioritisation or the cause area under discussion.

Hi Will, thanks for the comment. I agree 100% that it is very good for people to even look at hot button topics but keep such explorations offline.

Perhaps something I should have clarified above, and in danger of being perceived as speaking on behalf of others which is not my intention (instead I am trying to think of the least harmful example here): I was thinking that if I was someone really passionate about global health and doing it right, and coming from a strong Christian background, I might feel alienated from EA if it was required of me to frequently challenge my Christian faith.

So I think I was talking in terms of an attitude or value. For the above example of a Christian EA, and using another example of an atheist or at least agnostic EA who is super truth-seeking across the board, I could see the latter using this post to come to the conclusion that the Christian EA is not really EA as that person refuses to dive deep into the epistemics of their religious belief. This is what I wanted to highlight. And personally I think the Christian EA above is super helpful even for EAs who think they are not 100% truth-seeking: They have connections to lots of other Christians who want to do good and could influence them to do even better. They also understand large swaths of global population and can be effective communicators and ensure various initiatives from Pause AI to bed nets go well when delivered to Christian populations. Or they might just be a super good alignment researcher and not care too much about knowing the truth of everything. And the diversity of thought they bring also has value.

That said, I think "global truth-seekers" are also really important to EA - I think we would be much worse off if we did not have any people who were willing to go into every single issue trying to get ground contact with truth.

If helpful, and very simplistically, I guess I am wondering which of the two alternatives below we think is ideal?

Of course, one subset of Christians or other religious believers believe that the subjects of their religious beliefs follow from (or at least accord with) their rationality. This would contrast with the position that you seem to be indicating, which I believe is called fideism, which would hold that some religious beliefs cannot be reached by rational thinking. I would be interested in seeing what portion of EAs hold their religious beliefs explicitly in violation of what they believe to be rational, but I suspect that it would be few.

In any case, I believe truthseeking is generally a good way to live for even religious people who hold certain beliefs in spite of what they take to be good reason. Ostensibly, they would simply not apply it to one set of their beliefs.

That is a good point and an untested assumption behind my hesitation to "fully endorse truth-seeking in EA". That said, I would be surprised if all EAs, or even a majority, did everything they do and believed everything they believed due to a rational process. I mean I myself am not like that, even though truth-seeking is kind of a basic passion of mine. For example, I picked up some hobby because I randomly bumped into it. I have not really investigated if that is the optimal hobby given my life goals even though I spend considerable time and money on it. I guess I am to some degree harping on the "maximization is perilous" commentary that others have made before me, in more detail and more eloquently.

I think the modest amounts of upvotes and agree votes might be an indication that this "not being truth-seeking in all parts of my life" attitude is at least not totally infrequent in EA. Religion is just one example, I can think of many more, perhaps more relevant but it's a bit of a minefield - again, truth-seeking can be pretty painful!

I am not super confident about all this though, I made my comments more in case what I am outlining is true, and then for people to know that they are welcome by at least some people in the EA community as long as they are truth-seeking where it matters and that areas they are not investigating deeply does not too negatively affect having the biggest possible impact we could have.

I don’t think being truth-seeking means you need to over-analyse your hobbies - most hobbies don’t really involve truth claims

Yeah that was a bad example/analogy. Not sure if helpful but here is what GPT suggested as a better example/response, building on what I previously wrote:

"I understand your concern about over-analyzing hobbies, which indeed might not involve significant truth claims. To clarify, my point was more about the balance between being truth-seeking and pragmatic, especially in non-critical areas.

To illustrate this, consider an example from within the EA community where balancing truth-seeking and practicality is crucial: the implementation of malaria bed net distribution programs. Suppose an EA working in global health is a devout Christian and often interacts with communities where religious beliefs play a significant role. If the EA were required to frequently challenge their faith publicly within the EA community, it might alienate them and reduce their effectiveness in these communities.

This situation demonstrates that while truth-seeking is vital, it should be context-sensitive. In this case, the EA's religious belief doesn't hinder their professional work or the efficacy of the malaria program. Instead, their faith might help build trust with local communities, enhancing the program's impact.

Thus, the key takeaway is that truth-seeking should be applied where it significantly impacts our goals and effectiveness. In less critical areas, like personal hobbies or certain beliefs, it might be more pragmatic to allow some flexibility. This approach helps maintain inclusivity and harnesses the diverse strengths of our community members without compromising on our core values and objectives."

I agree mostly with the article, but I think truth-seeking should take into account the large fallibility of the movement. For example:

I don't see the problem with this. Ideas like "we should stop poor people dying of preventable illnesses" are robust ideas that have stood the test of time and scrutiny, and the reason most people are on board with them is because they are correct and have significant evidence backing them up.

Conversely, "weirder" ideas have significantly less evidence backing them up, and are often based on shaky assumptions or controversial moral opinions. The most likely explanation for a weird new idea not being popular is that it's wrong.

If you score "truth-seeking" by being correct on average about the most things, then a strategy of "agree with the majority of subject level scientific experts in every single field" is extremely hard to beat. I guess the hope is by encouraging contrarianism, you can find a hidden gem that pays off for everything else, but there is a cost to that.

There is no scientific field dedicated to figuring out how to help people best. I agree that deferring to a global expert consensus on claims that thousands of people do indeed study and dedicate their life to is often a good idea, but I don't think there exists any such reference class for the question of what jobs should show up on the 80k job board.

"The most likely explanation for a weird new idea not being popular is that it's wrong. "

I agree with much of the rest of the comment, but this seems wrong - it seems more likely that these things just aren't very correlated.

I think there are (at least) two reasons popular ideas might be, on average, less wrong than unpopular ones. One possibility is that, while popular opinion isn't great at coming to correct conclusions, it has at least some modicum of correlation with correctness. The second is that popular ideas benefit from a selection effect of having many eyeballs on the idea (especially over a period of time). One would hope that the scrutiny would dethrone at least some popular ideas that are wrong, while the universe of weird ideas has received very little scrutiny.

"Popular being more likely to be true" is only a good heuristic under certain circumstances where there is some epistemically reliable group expertise and you are not familiar with their arguments.

Modesty epistemology if taken to extreme is self defeating, for example majority of Earth's population is still theist, without the memetic immune system radical modesty epistemology can lead to people executing stupid popular believed ideas to their stupid logical conclusion. I also take issue with this idea along the lines of "what if Einstein never tried to challenge Newtonian mechanics because from the outside view it is more likely he is wrong given the amount of times crackpots have failed to move the rachet of science forward" . I also personally psychologically cannot function within the framework of "what if I am a crackpot against the general consensus", after certain amount of hours spent studying the material I think one should be able to suggest potentially true new ideas.

'New' is probably a lot of the reason

I'm curating this post. The facets listed are values that I believe in, but that are easy to forget due to short term concerns about optics and so on. I think it's good to be reminded of the importance of these things sometimes. I particularly liked the examples in the section on Open sharing of information, as these are things that other people can try and emulate.

Executive summary: Truthseeking and maintaining contact with reality is the most important meta-principle for achieving consequentialist goals, and there are many facets and techniques for pursuing it that are underutilized in the Effective Altruism community.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.