by Avi Norowitz

Summary

Animal Charity Evaluator’s (ACE’s) 2016 cost-effectiveness estimates indicated that corporate campaigns to improve the welfare of farm animals by The Humane League (THL) and other organizations was a highly cost-effective intervention. Although ACE’s 2017 estimates still show high levels of cost-effectiveness for corporate campaigns, the 2017 estimates do indicate a notable decline from 2016. In the case of THL, some of this difference disappears after adjusting for some changes in ACE’s assumptions. From a quantitative perspective, the remaining difference appears to have been caused by a large increase in budget combined with a smaller increase in equivalent years of suffering spared. This post also considers some qualitative considerations that may help explain the apparent changes in cost-effectiveness. This post ends with some reasons to put limited weight into this analysis.

ACE’s cost-effectiveness estimates: 2015-2017

Changes in ACE’s assumptions in 2017

ACE’s cost-effectiveness estimates, adjusted with 2017 assumptions

What factors might explain year-by-year changes in ACE cost-effectiveness estimates?

2016 represented an unusual year of US cage-free wins

ACE cost-effectiveness estimates don’t capture the importance of earlier groundwork

Reasons to put limited weight into this analysis

ACE’s acknowledges the limitations of their cost-effectiveness estimates

Comparisons between years could be misleading

Different metrics would lead to different results

Background

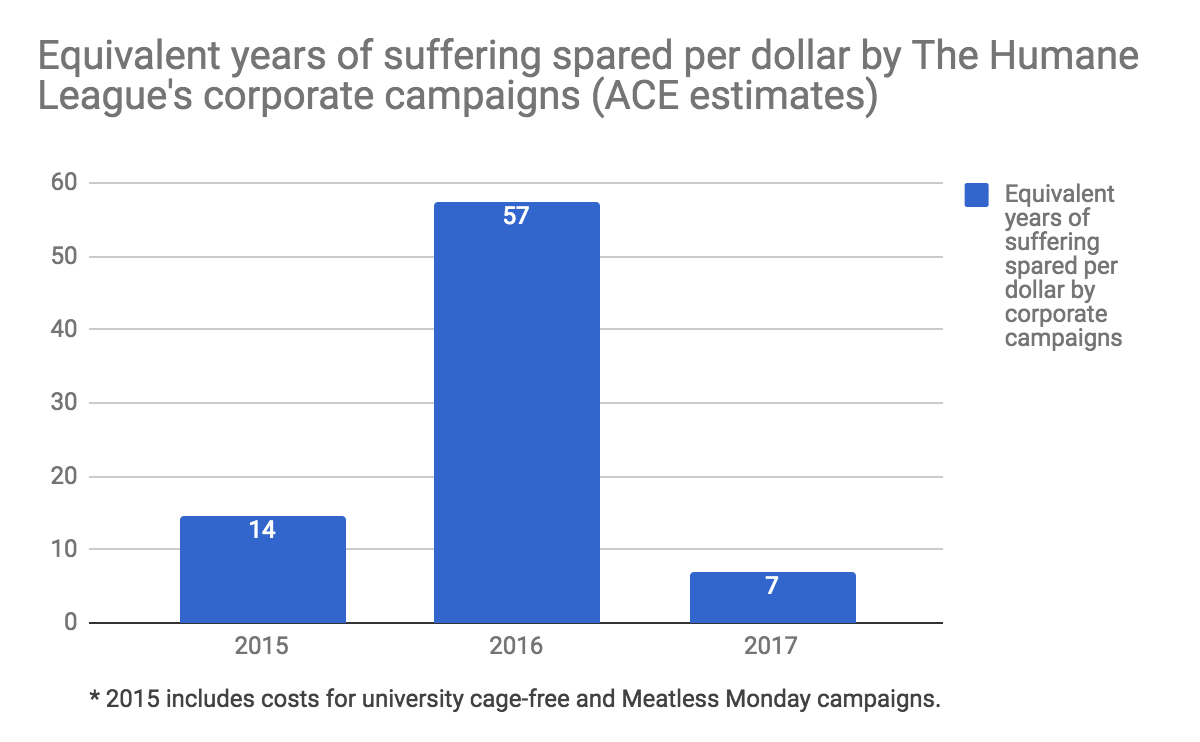

Animal Charity Evaluator’s (ACE’s) 2016 cost-effectiveness estimates indicated that corporate campaigns to improve the welfare of farm animals was a highly cost-effective intervention. ACE’s 2016 cost-effective estimate for The Humane League (THL), for instance, estimated that THL’s corporate campaigns during most of 2016 had the equivalent benefit of sparing ~57 animal years of suffering per dollar.[1] [2] This is in line with ACE’s 2016 estimates for other organizations, with THL performing somewhat better than other organizations.[3]

ACE’s 2017 cost-effectiveness estimates indicated lower levels of cost-effectiveness for corporate campaigns, with THL’s cost-effectiveness for their 2017 corporate campaigns declining to ~7 equivalent years of suffering spared per dollar.[4] While ~7 equivalent years of suffering spared per dollar still places THL’s corporate campaigns among the most cost-effective programs according to ACE’s cost-effectiveness estimates, it does represent a substantial decline from ~57. This post investigates the reasons for the apparent decline in the cost-effectiveness of THL’s campaigns between ACE’s 2016 and 2017 cost-effectiveness estimates.

Although I’m interested in the cost-effectiveness of corporate campaigns and related work in general, this post focuses on THL because of data limitations and time constraints.

ACE’s cost-effectiveness estimates: 2015-2017

To make comparisons over multiple years easier, I reproduced the “campaigns” section from ACE’s 2015,[5] 2016, and 2017 cost-effectiveness estimates of THL into a spreadsheet in Google Sheets.[6] [7] On the metric of “equivalent years of suffering spared per dollar,” THL’s corporate campaigns peaks to a high in 2016 and then declines to a low in 2017.

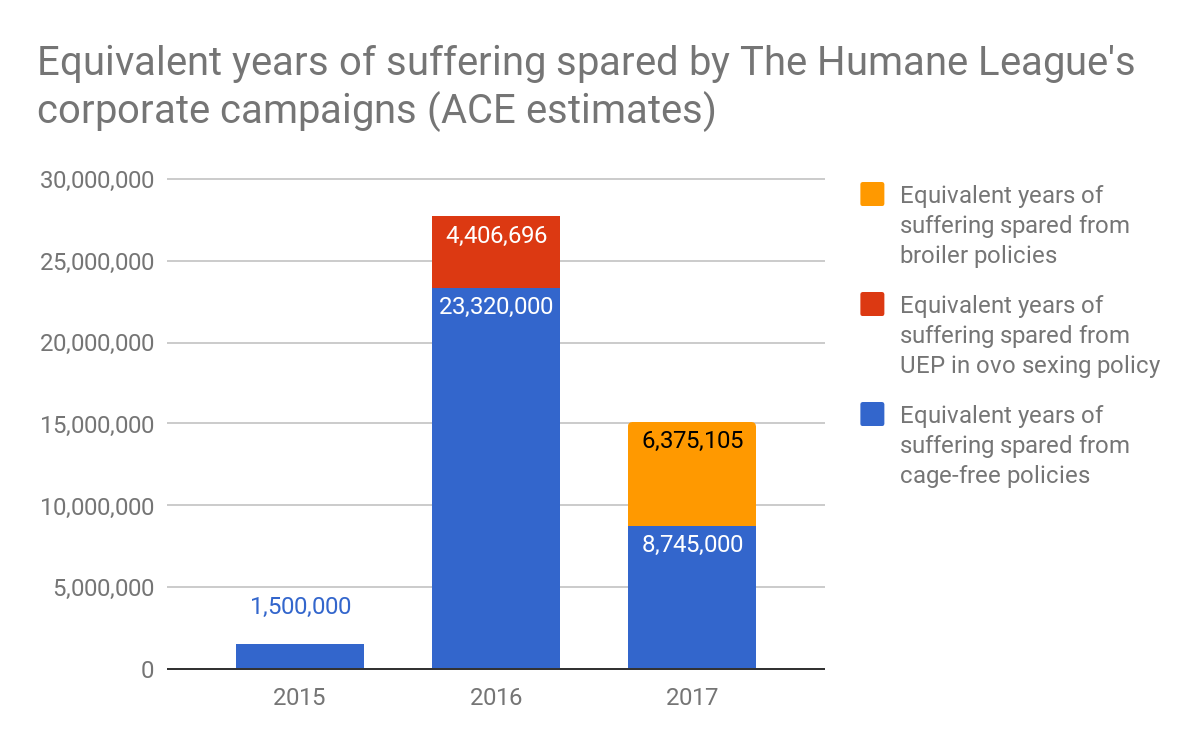

So, why does cost-effectiveness appear to decline in 2017? To investigate this, I generated a few more graphs. First, the following graph shows the “equivalent years of suffering spared,” without taking into consideration cost. The graph indicates a decline of this metric between 2016 and 2017.

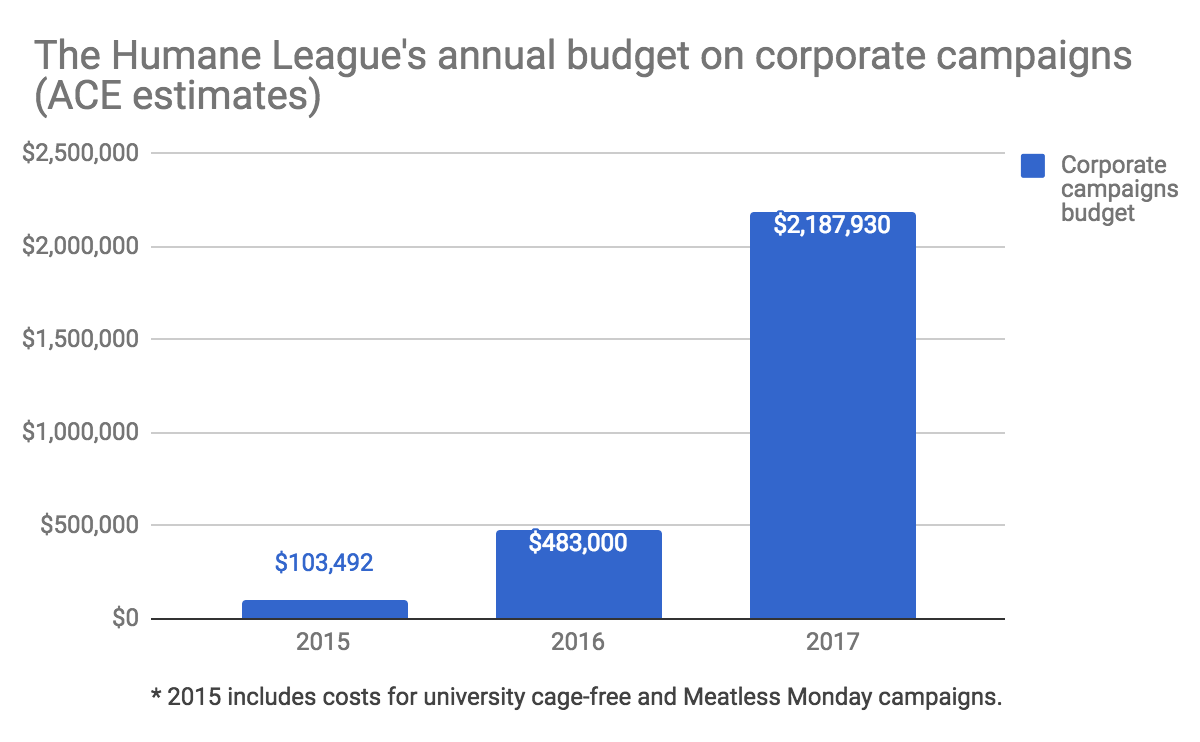

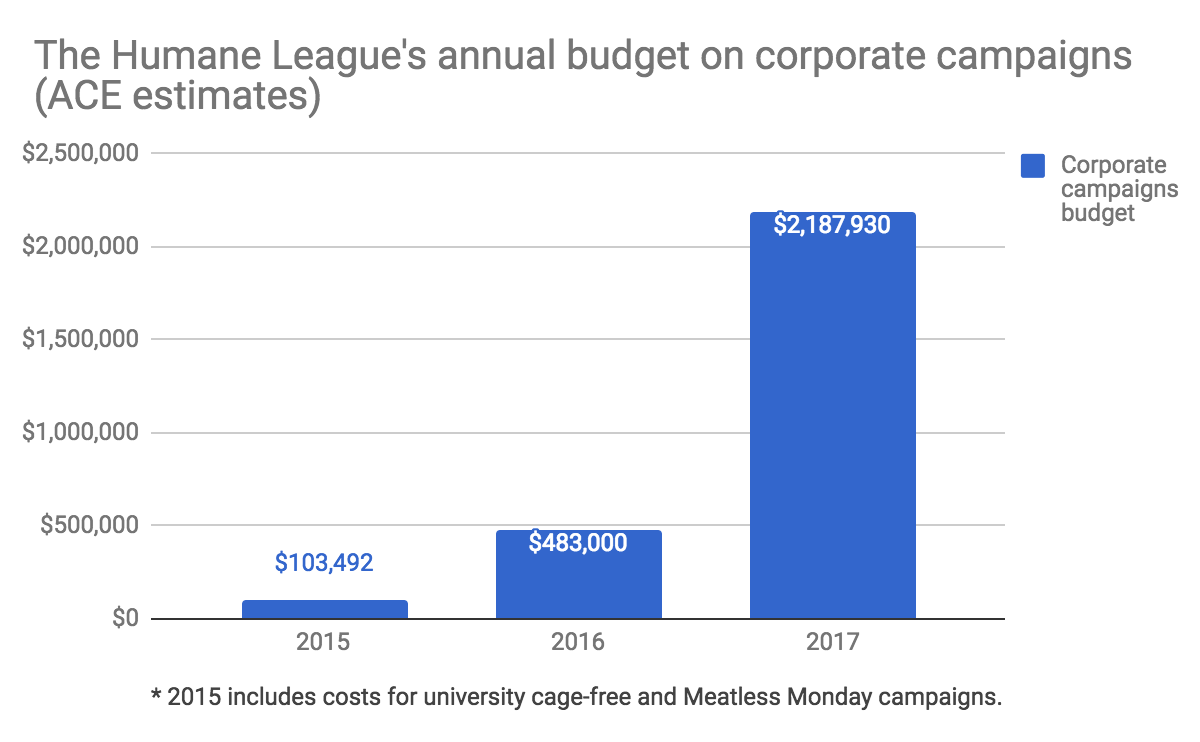

Second, the following graph shows THL’s annual budget on corporate campaigns, according to ACE’s cost-effectiveness estimates. This graph shows very large increase in THL’s annual budget for corporate campaigns in 2017.

The above graphs suggest that the an apparent decline in “equivalent years of suffering spared” and a large increase in costs both contributed to the apparent decline in cost-effectiveness in the estimates. As discussed in the following sections, however, there is more to the story.

Changes in ACE’s assumptions in 2017

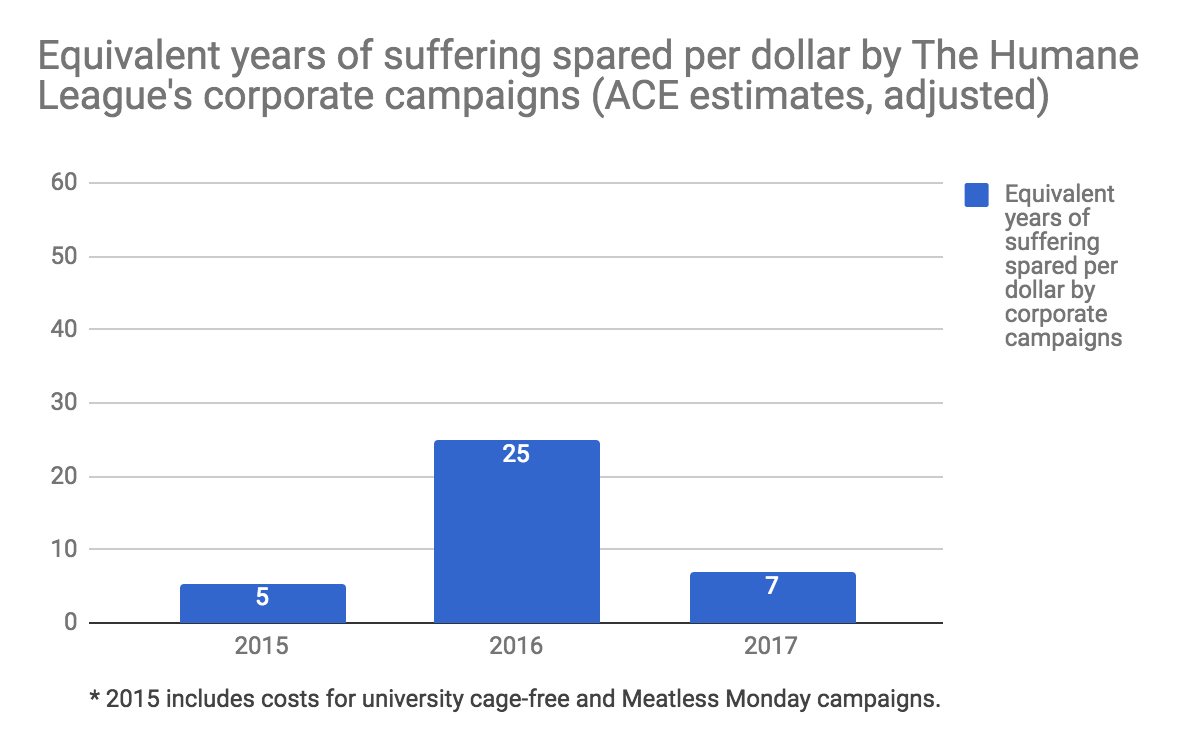

Upon further investigation, I found that much of the apparent differences are explained in changes in some of the assumptions in ACE’s cost-effectiveness estimates.

- In 2017, ACE added a new parameter for the “Probability that groups will follow through on the pledges that they made,” and assigned a value of 0.75 for THL. Since this didn’t exist in the 2015 and 2016 estimates, those estimates implicitly assume a probability of 1.00.

- In 2015 and 2016, ACE estimates that the “Proportional improvement in welfare due to cage-free policies” is ~0.10. That is, moving one hen from a battery-cage to a cage-free facility reduces 10% as much suffering as preventing the hen from existence. In 2017, ACE reduced this estimate further to ~0.05.

As demonstrated in the following section, applying these changes to 2015 and 2016 causes a decline in cost-effectiveness for these years, and also reduces the apparent decline from 2016 to 2017.

ACE’s cost-effectiveness estimates, adjusted with 2017 assumptions

I think ACE would probably agree that the assumptions described above should apply similarly to 2015 and 2016. Therefore, I’ve adjusted the estimates applying the 2017 assumptions to the previous years as well. With these adjustments, the apparent decline in cost-effectiveness between 2016 and 2017 still remains, but is smaller.

With these adjustments, we also see an increase in “equivalent years of suffering spared,” in contrast to the decrease we saw before these adjustments.

The adjustments, however, do not affect the spending, which substantially increased between 2016 and 2017. This increase in spending substantially outweighs the increase in “equivalent years of suffering spared” in the adjusted estimates.

What factors might explain year-by-year changes in ACE cost-effectiveness estimates?

2016 represented an unusual year of US cage-free wins

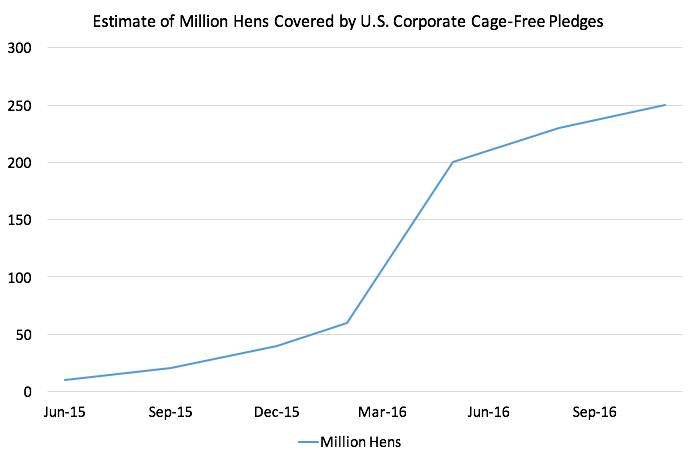

The following graph from Lewis Bollard at the Open Philanthropy Project shows an extraordinary increase in 2016 in the number of hens covered by US corporate cage-free pledges, representing more than ~80% of the US egg supply.

Given the unprecedented scale of these pledges, it may be expected that the years before and after 2016 appear less cost-effective on ACE’s cost-effectiveness metrics.

ACE cost-effectiveness estimates don’t capture the importance of earlier groundwork

For more than a decade, THL and other organizations have been laying the groundwork for the cage-free pledges in 2016. It’s likely that much of this groundwork, which included smaller, early wins, was necessary for the 2016 pledges to materialize. Therefore, attributing to the pledges in 2016 to the costs in 2016 may cause the 2016 work to appear more cost-effective than it actually was, while making earlier years appear less cost-effective than they really were.

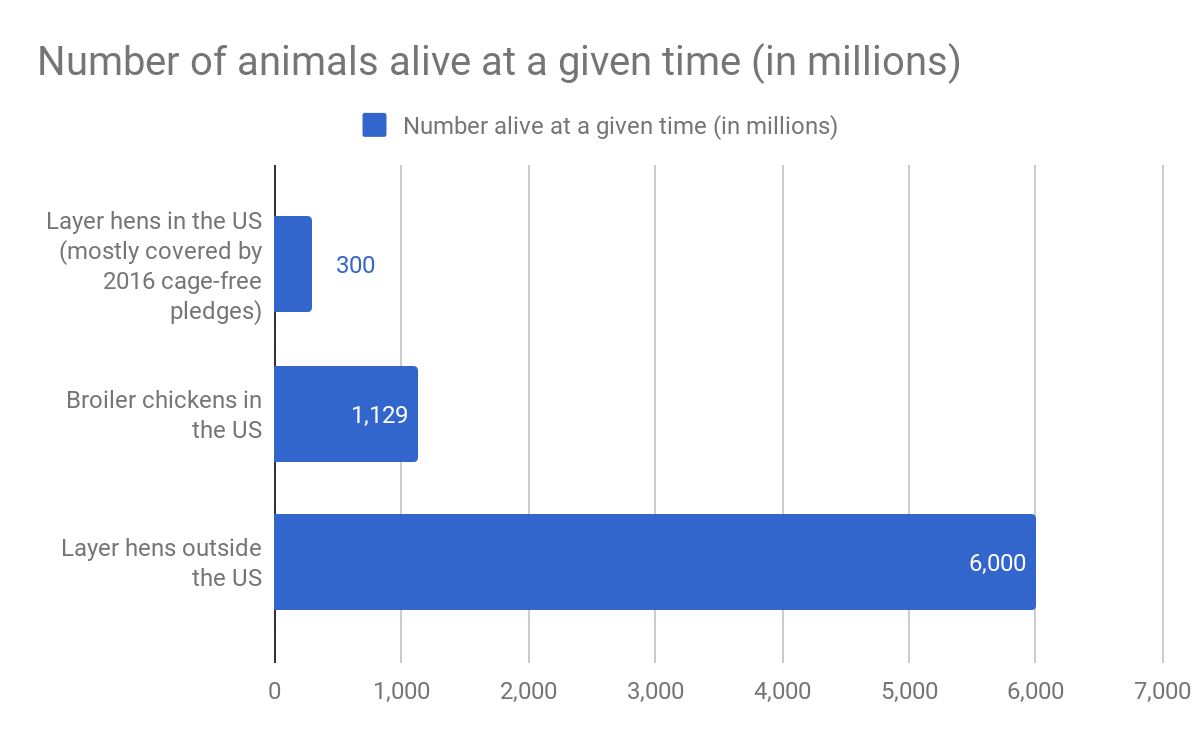

Moving forward, THL and other organizations are working on securing pledges from corporations to improve the welfare for broiler chickens in the US and layer hens outside the US. While the US cage-free pledges cover most of the 300 million layer hens in the US, representing a very large number of animals, these numbers are still small in comparison to the ~1.1 billion broiler chickens in the US and the ~6 billion layer hens elsewhere.[8] If THL and other organizations are able to secure pledges for a large proportion these animals over the next few years, it might be correct to attribute much of these pledges to the groundwork done in earlier years, including the smaller wins in 2017.

Capacity building

The large budget increase in corporate campaigns from 2016 to 2017 represents a large capacity building effort. It’s expected that capacity building may show limited benefits in the short term as employees are hired and trained, even if they yield large benefits in the long term. One consideration against this view, however, is that THL also substantially increased their corporate campaigns budget between from 2015 to 2016, and this increase was associated with a large increase in apparent cost-effectiveness.

Reasons to put limited weight into this analysis

This analysis represents an attempt to understand the apparent changes in cost-effectiveness, but there are multiple reasons not to put too much weight into it.

ACE’s acknowledges the limitations of their cost-effectiveness estimates

In regard to their cost-effectiveness estimates, ACE writes:

We want to be very clear: our cost-effectiveness estimates are approximations, they involve uncertain quantitative estimates, and they are subject to bias and error. They are not the only factor we consider when we evaluate interventions and charities—so our readers should interpret them carefully.

We do not advise our readers to accept our CEEs unquestioningly.

Comparisons between years could be misleading

ACE makes no claim that comparing cost-effectiveness estimates between years will lead to meaningful results, and there are reasons for concern that such comparisons could be misleading.

The adjustments I made for 2015 and 2016 were based on the two obvious changes I observed in ACE’s assumptions. However, there may have been other less obvious changes that affected these estimates. As an example, there’s some ambiguity about what time period each cost-effectiveness estimate covers, and which aspects of the estimates are based on past data vs. future projections. If estimates for different years vary in their approach in these areas, this may reduce the accuracy of these comparisons.

Different metrics would lead to different results

Although I’m focusing on the metric “equivalent years of suffering spared,” ACE also provides a different metric of “equivalent animals spared.” I prefer to focus on the former because I regard it as more morally relevant, but others might disagree. Focusing on the metric of “equivalent animals spared” would lead to a very different story about changes in cost-effectiveness, in which the changes are overwhelmingly dominated by the pledge THL secured in 2016 from United Egg Producers to end the culling of day old male chicks (a.k.a. “in ovo sexing”).

[1] ACE prefers to provide cost-effectiveness estimates as ranges rather than expected values, but for simplicity I’m just considering the expected values.

[2] The 2016 estimate will likely show similar but not identical results for “Equivalent years of suffering spared per dollar by Campaigns.” This occurs because each refresh at Guesstimate runs multiple Monte Carlo simulations, producing varying results each time.

[3] See the estimates for 2016 on the “All organizations” sheet on this spreadsheet.

[4] I’ve collected “equivalent years of suffering spared” for corporate campaigns and engagement for multiple organizations, and you can find a graph of this in this spreadsheet. I considered including this graph here, but decided against it because I worry that without following it up with an adjusted version, some readers might be misled.

[5] For 2015, the budget costs include university and Meatless Monday campaigns, so the cost-effectiveness of corporate campaigns may be understated.

[6] The original 2016 and 2017 Guesstimate estimates will likely show similar but not identical result for “Equivalent years of suffering spared per dollar by Campaigns.” This occurs because each refresh at Guesstimate runs multiple Monte Carlo simulations, producing varying results each time.

[7] I didn’t include the 2014 cost-effectiveness estimate because ACE includes only limited information on how they arrived at their estimates.

[8] Estimates are from this spreadsheet by Lewis Bollard at the Open Philanthropy Project. The layer hen estimate is from the “Top 15” sheet, subtracting the 300 layer hens in the US. The US broiler chicken estimate is from the “US States (2015)” which is extrapolated from USDA data and probably more accurate than the FAO data in the “Top 15” sheet. Although ~9 billion broilers chickens are slaughtered each year in the US, these animals are slaughtered after ~47 days so only 47/365 of these animals are alive at a given time.

This is very interesting thanks!

These projections of cost-effectiveness seem promising. I have a nagging related worry about what these campaigns have achieved so far, both in order to estimate a lower bound of their effectiveness, but which might also be relevant for future effectiveness. This worry resulted from the hypothesis that there is a displacement effect so that consumers and companies who buy cage free, will lower the price of caged eggs and thus increase demand from other consumers and retailers (in the US and potentially abroad).

Looking very briefly at the data it seems that the number of US cage free hens seem to have gone up in absolute terms by 25.8 million between Jan 2016-Oct 2017. However, it seems that total layer hens in the very similar time period from Dec '15 to Dec '17 have gone up by 37 million ( spreadsheet with sources ). In other words, the absolute number of caged hens seems to be increasing and corporate campaigns might have not had any effect at all so far. This seems to be in line with industry news.

This is also worrying especially if processed eggs from caged eggs might be exported to other countries in the future if the prices for eggs are further pushed down, or if processed eggs from caged hens are imported into the US.

But I'm not an export on this topic, so I would really like to hear someone to tell me what's wrong with this argument.

Hauke,

The layer hen flock size in December 2015 was unusually low because of an avian flu outbreak, so I don't think changes between December 2015 and December 2017 tell us much about the transition to cage-free.

It's also not clear why we should expect a transition to cage-free to increase the total number of layer hens based on price effects. If a buyer buys one less conventional egg, the expected supply of conventional eggs should fall by less than one because of price effects. On page 223 of Compassion by the Pound (2011), Norwood and Lusk estimate a decline of 0.91 eggs. But correspondingly, if a buyer buys one more cage-free egg, the increase in supply should increase by less than one, let's say 0.91 as well. I think it's a mistake to only consider price effects for the fall demand for conventional eggs for but not for the increase in demand for cage-free eggs. Of course it's fair to be on the lookout for evidence that one effect is stronger than the other, but the increase in egg supply from 2015 to 2017 is far better explained by a recovery from an avian influenza outbreak so I don't think it provides any meaningful evidence on this issue.

And if we consider price effects overall, the fact that cage-free egg production is somewhat more expensive than conventional egg production should cause a small decline in overall demand for eggs.

I think there is a risk that food corporations will renege on their pledges, perhaps arguing that the cage-free egg supply is insufficient. The parameter "Probability that groups will follow through on the pledges that they made" in ACE's estimates appear intended to capture this risk, and this is assigned a probability of 0.75 for THL in 2017. I think this risk underscores the importance of the work the animal organizations plan on follow-up with food corporations to ensure they follow through on their pledges, and that they start the transition early. I think this need for follow-up represents another limitation of ACE's cost-effectiveness estimates, since they assign all the benefits to the year of the pledges even though follow-up work will be required in future years.

Avi

Wouldn't you need to look at the price elasticity of egg consumption rather than absolute trends to conclude whether / to which degree the reduced demand by some is moderated by replacement effects?

It also seems that, at least in the medium term, lower prices cannot necessarily support the same scale of egg production so the market would, hopefully, shrink, no?

Yes, absolutely, but the elasticity is somewhat hard to calculate (somewhat should try this though!). My example from above is just making a conservative assumption that the replacement effect is extreme. Of course it could be that there would have been a 37 million hen increase independent of corporate campaigns and that corporate campaigns have moved 25.8 million of those hens out of cages.

I mentioned this in a previous comment, but in case readers missed it:

The increase in flock size from December 2015 to December 2017 is far better explained by the US egg industry's recovery from an avian influenza outbreak than by cage-free pledges.

Norwood and Lusk (2011) estimate based on price elasticity data that, on the margin, a reduction in demand for 1 conventional egg causes a reduction in supply of 0.91 conventional eggs. But correspondingly, an increase in demand for 1 cage-free egg should lead to an increase in supply of less than 1 cage-free egg. So it's unclear why we should expect the transition to cage-free to increase the number of layer hens. If anything, the increase in prices caused by the transition should reduce the number of layer hens.

Thanks for this. The true cost-effectiveness estimate should still be reduced by whatever the displacement effect is, even if it isn't large. If we expect 9% of a conventional egg to be consumed for switching demand to 1 cage-free egg, then we should adjust the impact of the campaign downward by whatever the welfare effect of 9% of a conventional egg is.

A useful exploration, thank you. I hadn't really thought of the cost effectiveness estimates not taking account for previous efforts, so this is useful. It reinforces the importance of really thinking carefully about how different organisations interrelate before we make judgements about comparative effectiveness - and especially before we make important decisions (either as a movement, or as individuals, developing career paths etc) in the light of these judgements. This is something I've been thinking a lot about since reading Harish Sethu's post for The Humane League Labs on a similar topic. [1]

In line with Hauke Hillebrandt's comment about nagging related worries about the campaigns, I feel it's worth re-emphasising the real uncertainty about the long-term implications of these campaigns, summarised by Sentience Institute [2] (and expressed by many upset abolitionists, whenever welfare campaigns or organisations are mentioned): will they lengthen the existence of factory farming by encouragin humanewashing?

Combined with information suggesting that "cage free" isn't actually much of a real welfare improvement [3], it makes me sceptical of the overall value of welfare interventions. And now Hauke Hillebrandt's comment has made me even more sceptical!

All these things combined might make considerations of cost efficiency of the intervention type fairly irrelevant - potentially these are even consideartions of the efficiency of increasing total animal suffering?

I'm possibly being overly negative here - but when THL is the only charity that ACE has recommended in all review periods, and has previously recommended MFA (who run similar programmes), it seems pretty fundamental to EAA.

[1] http://www.humaneleaguelabs.org/blog/2018-01-30-how-ranking-of-advocacy-strategies-can-mislead/

[2] https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/foundational-questions-summaries#momentum-vs.-complacency-from-welfare-reforms

[3] https://www.openphilanthropy.org/blog/new-report-welfare-differences-between-cage-and-cage-free-housing

Jamie,

I worry that people might misunderstand the views of Sentience Institute from your comment. The Sentience Institute report summarizes arguments for both positive (momentum) and negative (complacency) long-term effects of welfare reforms. But Jacy and Kelly, who run Sentience Institute, are in favor of welfare reforms, although they do believe anti-speciesism has more positive expected value in the long term. [1] And Sentience Institute's survey [2] of EAA researchers similarly indicates strong support for momentum rather than complacency in the long-term.

More broadly, the sign of the long-term effects of all EA interventions are uncertain, and this is not a problem specific to welfare reforms. (Even the sign of the short-term effects of most animal interventions are uncertain.)

I also don't think the statement that "'cage-free' isn't actually much of a real welfare improvement" is a fair summary of the Open Philanthropy's report. The blog post says, for instance: "We continue to believe our grants to accelerate the adoption of cage-free systems were net-beneficial for layer hens ... In addition, it seems clear to us that cage-free systems have much higher welfare potential than battery cage systems – that is, the theoretical highest-welfare hen housing system would not contain cages."

That being said, I think it is fair to say that ACE regards cage-free as a small improvement, since their 2017 cost-effectiveness model assumes that moving one hen to a cage-free facility reduces only 5% as much suffering as preventing the hen from existence. But it's also notable that ACE's cost-effectiveness models still place corporate campaigns and engagement for welfare reforms as the most cost-effective of the interventions in their estimates, even though they adjust for this pessimism.

(Of course the effects could go negative as you suggest, i.e. if they change their mind and decide cage-free increases 5% as much suffering. But again, this problem is not unique to welfare reforms, as evidenced by the observation that ACE's estimates of most interventions have confidence intervals that span the negatives.)

For what it's worth, my own view is that ACE's cost-effectiveness estimates are far too pessimistic about the benefits of cage-free vs battery cages. (Though I also think they're too optimistic about some other assumptions.)

Avi

[1] This is from memory and hopefully I've characterized their positions accurately.

[2] https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/blog/eaa-researcher-survey-june-2017