Introduction

I spoke at EA Global: Boston 2023 about ending restrictive gender norms as an EA opportunity. I discussed my research in India, in which we designed and evaluated class discussions about gender equality embedded into the school curriculum. Our randomized control trial (RCT) found that the intervention succeeded in eroding students' support for restrictive norms and the curriculum is now being scaled. Here's an edited transcript of the talk.

Key points include:

- A discussion on economic development vs. gender inequality: despite significant economic growth in India, as indicated by rising GDP per capita and improvements in general well-being, gender inequality measures, particularly the skewed sex ratio, have worsened.

- Overview of the implementation of an RCT in Haryana aimed at shifting gender norms and attitudes through educational interventions targeting school children.

- An evaluation of the efforts to change gender norms in low and middle-income countries, assessing their tractability, neglectedness, and significance within broader economic and social frameworks.

EA Global Boston: 2023 talk

Speaker background: Seema Jayachandran

Seema Jayachandran is a Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University. Her research focuses on gender inequality, environmental conservation, and other topics in developing countries. She serves on the board of directors of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) and leads J-PAL’s gender sector. She's also a co-director of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s programme in developing economics.

Overview of gender norms in India

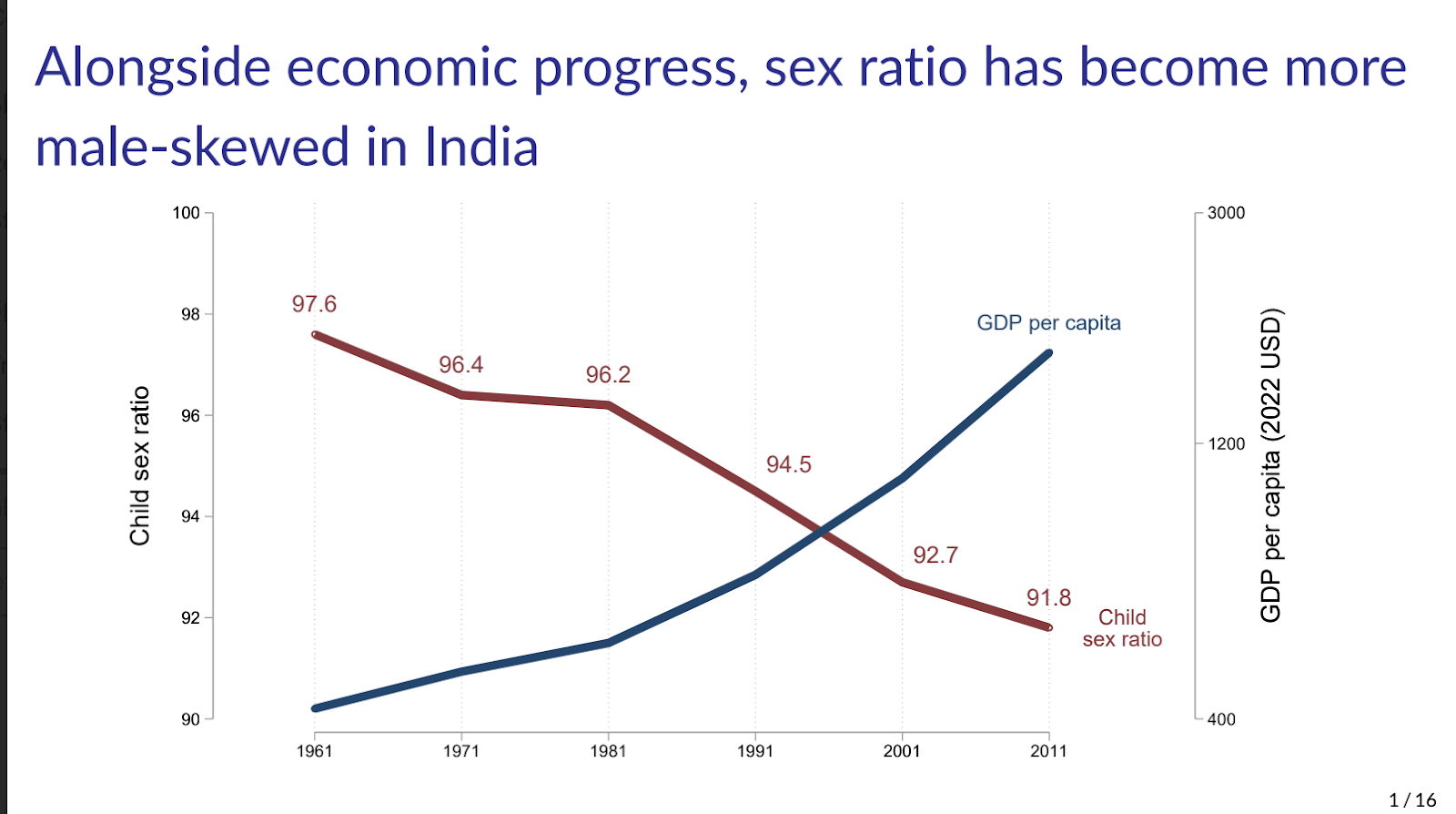

I'm going to talk about gender norms with a focus on low and middle income countries. I'm going to mostly talk about India, because that's where my research on this topic is based. I'm going to start with this picture, which shows one of the motivations for why I decided to work on this topic (see slide below). It is a picture of progress and regress in India over the last 60 years.

- The blue line shows GDP per capita. Over the last few decades, India's economy has grown and that has improved the well-being of people from rural villages to the fancy software campuses in Bangalore. There have been incredible improvements in health and well-being.

- The red line is the negative progress. It shows the regress that has happened over that same period on one measure of gender equality, namely the ‘skewed sex ratio’. So what I'm depicting here is, “for every 100 boys, how many girls are there in society?” It was not parity at the beginning of this period, but it's just gotten worse in subsequent decades. So this is from census data, and it stops in the most recent census in 2011. Right now, there are 92 girls alive for every 100 boys.

Impact of technology on existing cultural norms

Why has this measure of gender equality deteriorated? At the heart of sex selection, or the preference for sons over daughters, is a cultural norm and need. Values in India emphasize the importance of having a son because, in the joint family system, elderly parents or older adults typically live with their son, who then takes care of them, inherits their property, and fulfills certain religious obligations. Consequently, the practice of favoring sons has evolved into a status symbol and there is stigma associated with not having any sons. I actually believe that this norm has not worsened over recent decades. However, it has conflicted with changes in the economic environment that are usually seen as progress. As depicted in slide 2 below, the use of ultrasounds has become significant. Historically, people always preferred sons, but it was only since the mid-1980s that they had the technology, through ultrasounds, to determine if they were carrying a female or male fetus and then selectively abort female fetuses. Additionally, as people grow wealthier, they can afford such technology, increasing its usage.

The slide also shows a general decline in fertility. Technological advancements are often linked with economic development, which is generally welcomed. Declining fertility rates are also tied to economic development. Initially, as shown in the first slide, people had six children, but now they have two. This shift is crucial because, especially if you're Hindu, it's important to have at least one son to take care of you and to light your funeral pyre. Previously, with six children, the likelihood of naturally having a son was high. Now, with only two children, a quarter of families may not naturally have a son, leading them to consider abortion if the second pregnancy results in a girl. Therefore, while the cultural norm remains unchanged, the changing economic landscape exacerbates the situation.

Other dimensions of gender inequality

There are additional aspects of gender inequality in India, as illustrated in slide 3 below. For instance, even when healthcare is free, parents often prioritize their son’s health over their daughter’s. This is partly because visiting a doctor takes time and they are more likely to make the time for their son. Another dimension is the prevalence of sexual harassment and violence in public spaces. Additionally, the rate of female employment is notably low and has been declining over recent decades. I don’t believe that the norms regarding seclusion of women from interacting with men or the status of being the primary breadwinner have shifted significantly. However, now that many families can sustain themselves on a single income, they can afford to impose restrictions on their wives. These restrictions often include limitations on women’s freedom to leave the house unaccompanied or without permission, even for simple tasks like picking up their children from school. Consequently, women have very limited personal autonomy to make choices about their lives.

Hopefully, most people are on board with the idea that the world would be better if we had removed some of these reduced opportunities for girls and if women had more freedom.

Policy proposals to reduce gender inequality

From a policy perspective, addressing gender equality issues involves a complex array of factors. Fortunately, many policymakers are motivated to resolve these issues, either from a rights standpoint or due to the pragmatic benefits for governments. For instance, increasing female participation in the workforce would immediately boost GDP per capita. Additionally, the problem of millions of young men struggling to find wives raises concerns about potential increases in civil unrest or crime. As a researcher working on gender equality, I engaged with policymakers in Haryana, a state in North India. I am affiliated with J-PAL, which has strong relationships with various state governments. During discussions, the government of Haryana expressed interest in refining a policy aimed at correcting the skewed sex ratio. The policy involved financial incentives for families that have daughters and opt for sterilization—effectively, though not overtly, paying people to have daughters.

In our research, we've identified persistent social norms as a central challenge. Changing the shame associated with not having a son is crucial. In response, we proposed a new approach to the government partners in Haryana: an intervention to shift these norms and attitudes. We decided to target children, who are generally more open to changing their perceptions of what is morally right or wrong. Working through schools, which almost universally enroll children, provides a platform not only for academic education but also for shaping moral values and attitudes. This approach, while potentially contentious, aligns with the government's progressive stance on equal rights. The project has since expanded to focus more broadly on advancing women's rights in areas like physical mobility, employment, education, and healthcare.

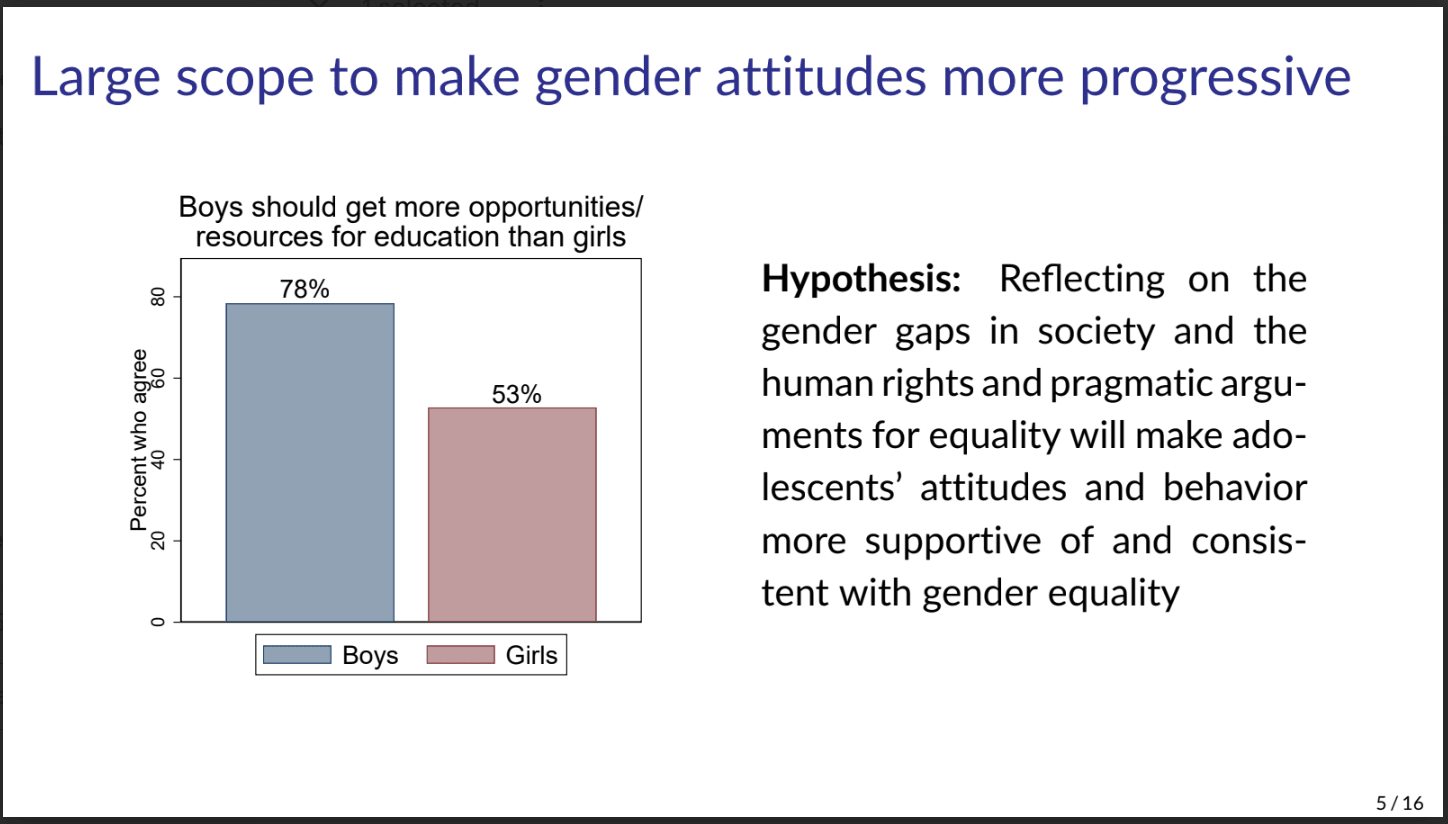

Working with schools to shift attitudes about gender equality

Statistics indicate significant gender inequality in India (see slide 5 below). In addressing this issue, we opted to engage with children, although some may argue that they are too young and have not yet absorbed societal norms. However, our baseline survey of 12-year-olds in Haryana reveals otherwise. We found that three-fourths of boys and over half of girls agreed that boys should receive more educational resources than girls. The dissenting girls did not advocate for more resources for themselves but for equality. This indicates that by age 12, both boys and girls have internalized the notion that boys are more deserving than girls.

This project was based on the simple hypothesis that if children spend time contemplating the gender equality existing in their society and consider both rights-based and pragmatic arguments for equality, they would become more progressive. These discussions are expected to make them more supportive of gender equality, influencing their actions to align more with egalitarian principles. This change might be modest at first, particularly as we are not altering the broader societal context immediately, but fostering belief in equality is a crucial step towards changing behaviors. For instance, as they grow older, boys who are educated about gender equality might become more supportive of their wives working, and families might be more likely to invest equally in the health of their daughters and sons.

Taaron Ki Toli program in practice

As a researcher, my role involves scanning the evidence, identifying gaps, and understanding what might work in various contexts. I'm not an expert in designing interventions to change attitudes; this specific intervention was crafted by a remarkable NGO named Breakthrough. The way this partnership functioned is typical of my projects with governments: the government finds an idea intriguing but acknowledges the bureaucratic challenges in implementing it, such as budget allocations or changing the teacher training curriculum. To test the concept, the government of Haryana granted us permission. They provided a letter allowing us to approach school principals, giving us an open door to collect data and engage an NGO to modify the school curriculum and conduct classes during the regular school day.

This was the setup for the intervention we tried with Breakthrough, which they named Taaron Ki Toli. It was implemented in government secondary schools for just over two school years, with Breakthrough’s hired teachers delivering 45-minute classes on gender equality approximately every three weeks.

The curriculum was notably interactive, which likely contributed to its success, keeping it engaging for the students. There was concern that this might be a class boys would disengage from, but it potentially offered them critical thinking skills, typically under-provided in the regular curriculum. The curriculum covered a range of topics; in some sessions, students discussed and debated various statements, sharing whether they agreed or disagreed and why. One session focused on aspirations, revealing to boys in co-ed schools that their female peers had similar career goals—apart from unique cases like aspiring to be a cricket player.

Another session involved discussing tolerance towards discrimination. A particularly impactful class had students break into groups to discuss who performed household chores like cooking, cleaning, and laundry. When reconvening, the consistent answer was that women and girls were the primary doers of these tasks. The Breakthrough facilitator then challenged this norm by asking why, if women are purportedly better at these tasks, they aren't the ones cooking in restaurants or at large events where they could use their skills on a broader scale. This question aimed to highlight the disparity in how societal roles and power are distributed and whether being confined to cooking at home truly utilized a woman's talents and provided her with equivalent societal influence.

This curriculum aimed to make students critically examine and defend their ingrained beliefs, revealing inconsistencies in their justifications for gender norms. The hopeful aspect of this theory of change is that defending inequality of opportunity becomes more challenging than advocating for equality of opportunity when one is forced to scrutinize and justify one's stance.

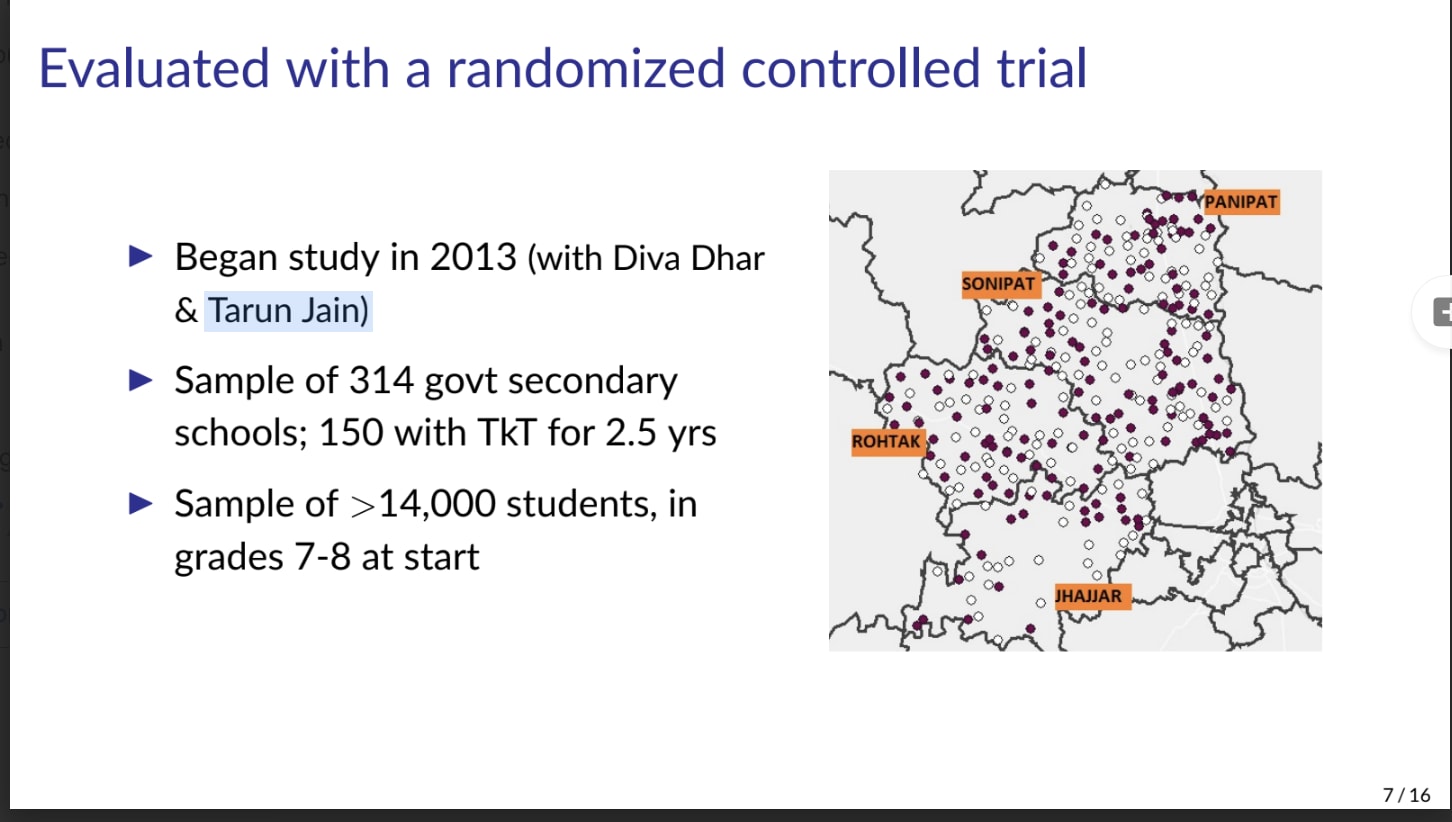

Summary of the intervention

This is a summary of the intervention we evaluated as a randomized control trial (RCT), which we started discussing in 2012 and began data collection for in 2013. The research was conducted alongside Diva Dhar and Tarun Jain. We focused on four districts in Haryana, sampling 314 government secondary schools, which essentially encompassed all such schools in the area, selecting no more than one per village. From these, we randomly assigned 150 schools to implement the Taaron Ki Toli (TKT) intervention by Breakthrough, while the remaining schools continued with their usual curriculum. The intervention sometimes displaced a bit of time from subjects like history or from math, and the distribution was fairly even across the board.

We enrolled students from grades seven and eight at the start, and they continued to receive the curriculum as they advanced to grades eight, nine, and partially in grade ten. All students in the treatment schools participated in the curriculum, and we also selected a subset of these students to be part of our study sample for detailed tracking and surveying. In total, including students from control schools, our sample size exceeded 14,000 students, which is quite substantial. The purpose of such a large-scale study was not only to assess the immediate impact of the intervention—whether it shifted beliefs—but also to monitor long-term effects. Specifically, we aimed to see if these changes in beliefs could translate into actionable behavior changes, such as a grown man, previously a boy in the program, considering his wife's desire to work and supporting her right to do so if she chooses.

Findings (three months after program ended)

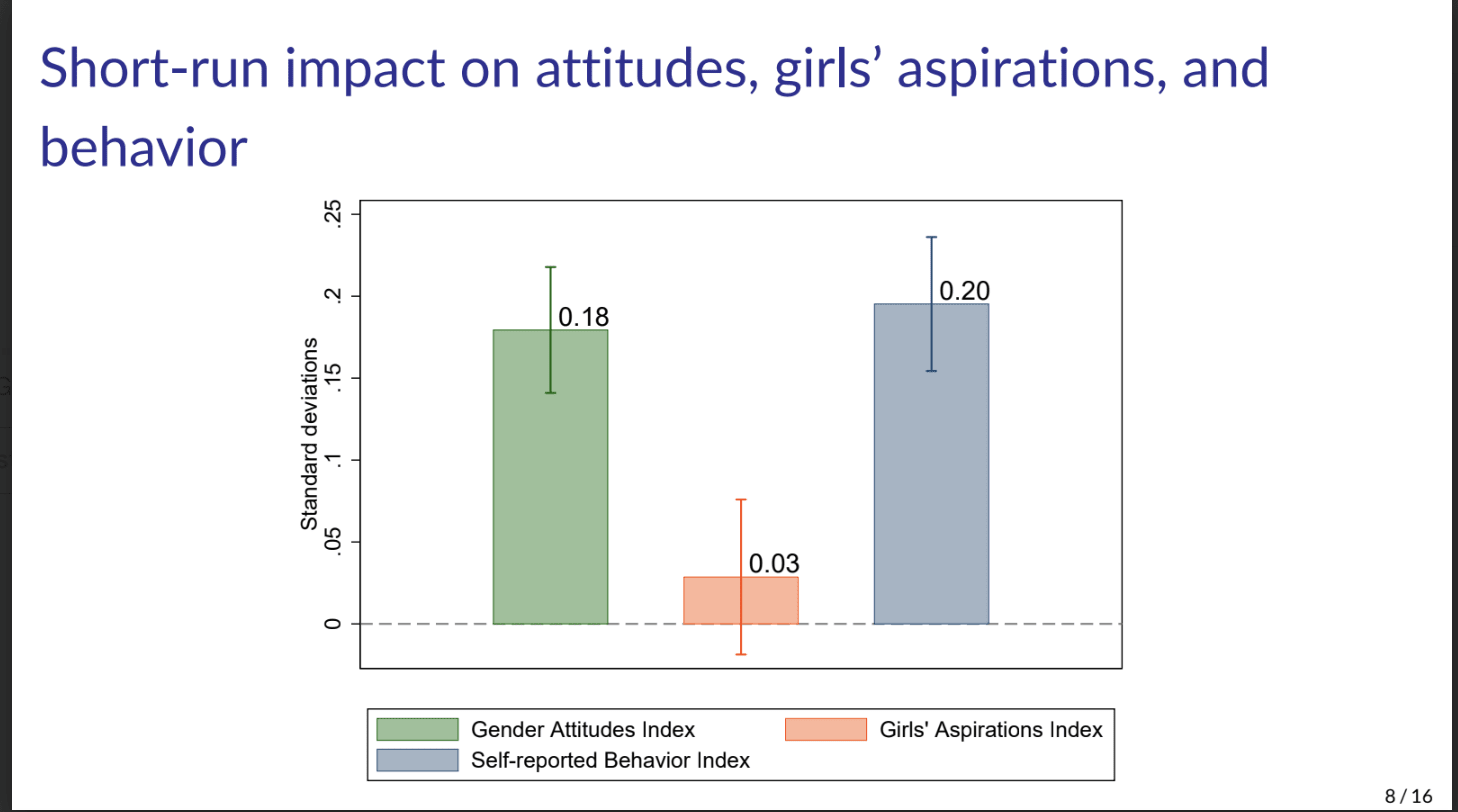

After the intervention concluded, we conducted our first follow-up survey three months later, giving us insights into the impact of the program after students had participated for two and a half years. Assessing changes in norms and attitudes is challenging, particularly in the short term, because it revolves around understanding deeply held beliefs. Our primary measure was gender attitudes, assessed using several questions similar to those from World Values Surveys, such as whether "Boys should get more opportunities/resources for education than girls." We combined these into an index where a higher score indicates stronger support for gender equality.

Our findings showed a noticeable increase in support for gender equality, represented by the first green bar in the results chart. However, we observed no significant change in the second outcome we pre-specified, which was aspirations, specifically for girls. This lack of change might be attributed to the already high baseline; about 80% of the girls expressed a desire to have a career and work outside the home after marriage, which contrasts sharply with the current female employment rate in India of 20-25%.

We also developed a behavior index based on self-reported behaviors. We focused on areas where children might have some influence, such as household chores, advocating for their older sisters' educational opportunities, and their own college ambitions. Here, we observed that participants reported behaviors more aligned with gender equality. This suggests that while the intervention may not have shifted aspirations—possibly due to already high expectations—it did influence behaviors in a way that reflects a move toward more egalitarian views.

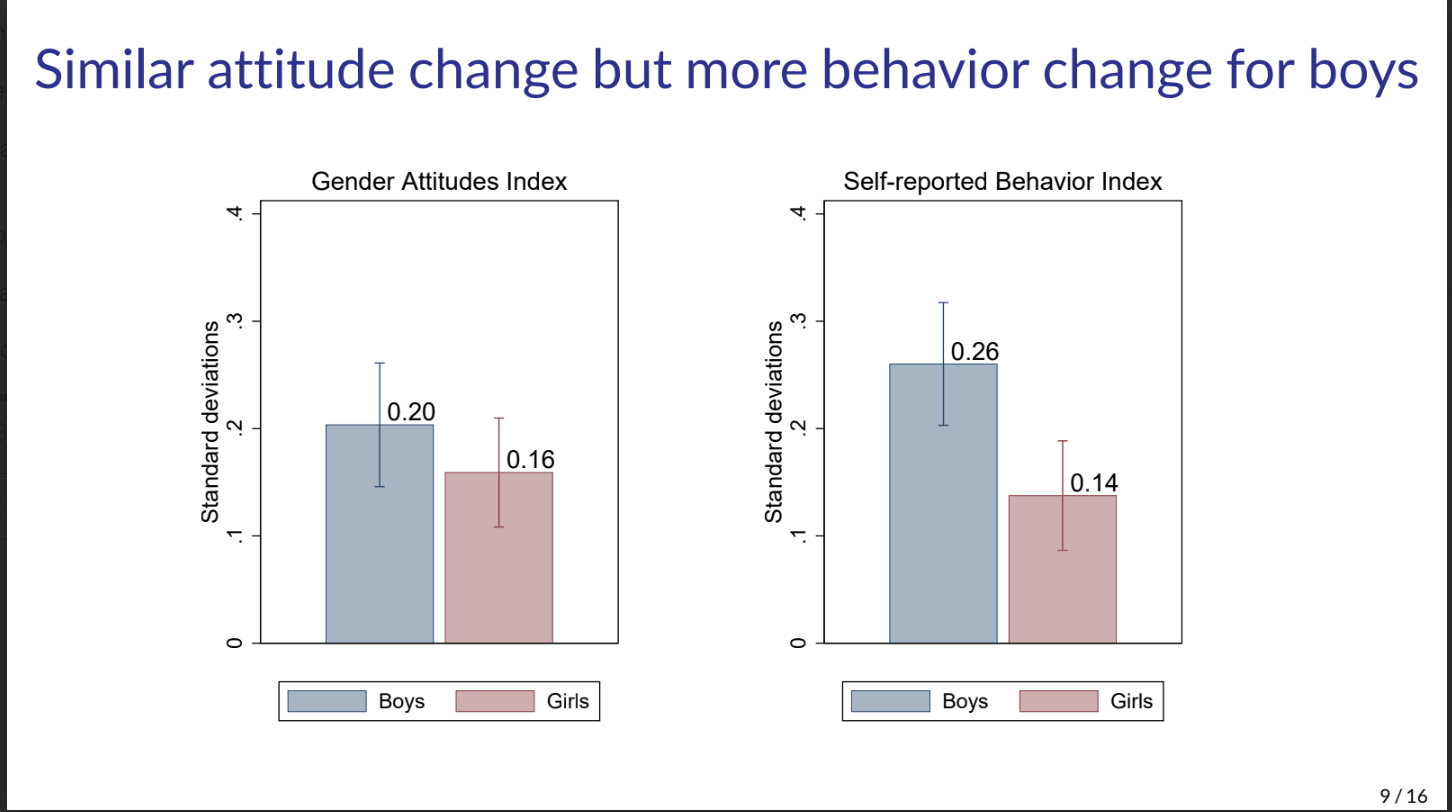

What I showed you before involved polling both boys and girls, and when we analyze the data separately for each gender (see below), we observe a similar positive shift in attitudes among both groups. Initially, girls were more progressive than boys, but both genders showed improvement. However, a key difference emerges in behavior change between boys and girls. This disparity likely stems from the fact that holding a belief isn't the sole factor influencing one’s actions. Translating a newfound belief in gender equality into actual behavior requires a degree of societal power.

Mechanically, the results show that while boys reported increasing their participation in chores, girls did not report a corresponding decrease in their chores. This suggests that those with privilege, such as boys, can more easily choose to relinquish it, whereas those without privilege, like girls, find it harder to make unilateral changes, such as going on strike from doing chores. Moreover, in activities that don’t involve such asymmetry, like advocating for an older sister’s educational ambitions, boys reported more active involvement than girls. This is likely because boys face less fear of backlash or punishment for such actions.

These findings highlight the critical importance of involving boys and men in interventions aimed at shifting gender norms, as their participation can significantly influence the success of these initiatives in fostering broader societal change.

Findings (2.5 years after program ended)

Okay, so that was three months after the program ended. We then went back and conducted another survey two and a half years after the program had ended (see slide below). By this time, the kids hadn't been exposed to the curriculum for two and a half years. This was probably the biggest surprise of the project for me. We observed persistent effects: people still held more progressive gender attitudes, and this persistence was noted for both boys and girls. We still saw positive effects for girls, but there was some fadeout. For boys, the persistence of these attitudes was almost complete. We aren't entirely sure why this is, but it might relate to what I mentioned earlier: perhaps boys were able to put their beliefs into action and received positive reinforcement for their actions, whereas girls did not experience this as much. This seemed to suggest that the changes stuck more significantly with boys.

One aspect I'm not going into detail about in this talk, due to time constraints, is the concern that respondents might simply be telling us what they think we want to hear, rather than what they truly believe. To address this, we implemented various methods in the study to check for sincerity. Additionally, the persistence of these results gives me some reassurance. For the longer-term results, we also incorporated what economists call "revealed preference" measures, which are objective measures. For example, we had a public petition against the dowry system that participants could sign, with their names being published in the local newspaper. Signing this petition was somewhat costly, in terms of social exposure, so it required having some skin in the game. This helped ensure that the expressions of belief were genuine, as it was not just a matter of saying something pleasing to the researchers without any real belief.

Findings (5.5 years after program ended)

More recently, at the beginning of 2023, we completed a third round of data collection. At this point, the participants are between 20 and 21 years old, marking the first time we're observing them as adults. This provided an opportunity to examine hard outcomes, which I believe are particularly compelling for politicians and government officials. Changes in attitudes might not be especially exciting for them, but they might be interested if there are more women working or if there are fewer child marriages. However, we did not see an effect on women’s employment or their age at marriage, which was disappointing. This finding isn't the most surprising to me, especially after earlier observations where behavior changes were more pronounced among boys than girls. It's possible these young women wanted to work, but they faced challenges convincing their husbands or in-laws, which is difficult. Our intervention didn't facilitate a change in the attitudes of these other influential people.

That said, we did observe that these young women reported a greater sense of personal autonomy. They indicated they felt more autonomous, were able to travel 15 kilometers via rickshaw or bus more frequently, had greater access to a cell phone, and could maintain friendships with the opposite sex. While such outcomes may not capture the attention of a chief minister, they represent meaningful changes in the lives of these women.

In this last round, we also decided to explore spillovers within families. We surveyed the younger siblings who had never participated in the intervention and observed that they held more progressive attitudes. This suggests that interventions like this can not only directly affect participants but also indirectly influence their families. Initially, I wouldn’t have considered the possibility of upward spillovers to the parents; my model of the world was that parents were the obstacles with their regressive views. We aimed to change the younger generation and bypass the parents through schools. However, anecdotally, we found that children would discuss what they learned with their parents, who seemed curious and receptive, challenging my previous assumption that parents are staunchly invested in maintaining the status quo.

We then surveyed the parents to see if their attitudes had shifted. Overall, we didn't see a uniform change, but specifically in one dyad, we observed significant changes: if a boy had participated in the program, his father showed more progressive attitudes by about 0.3 standard deviations. To contextualize the magnitude of these standard deviations: 1) the gap between boys and girls in the control group in terms of support for gender equality is about 0.5 standard deviations, which reflects the typical difference in attitudes (e.g., 75% of girls vs. 50% of boys supporting equality). So, while the intervention did not make a boy as progressive as a typical girl, the change was still considerable. 2) Another perspective is that, among those who held conservative views, 16% changed their views to support gender equality as a result of the intervention—a substantial effect. This indicates the potential of such interventions, though no single approach will solve such a complex problem entirely. Additionally, increasing the "dosage" of the intervention through more years could potentially enhance these effects. Thus, the fact that fathers exhibited even greater change than their children directly impacted by the program underscores the broader transformative potential of these interventions on societal norms.

Scaling opportunities

Looking ahead, if we can secure additional funding, our aim is to investigate further aspects such as the employment status of the male participants' wives or the sex ratio of their children. This is the direction we hope our research will take. Meanwhile, after observing promising results and the enduring impact from our initial study, J-PAL South Asia and Breakthrough have been actively engaging with various state governments to discuss scaling the intervention.

Interestingly, the initiative to scale up our program was adopted not in Haryana—where the original study was conducted—but in two other North Indian states, Punjab and Odisha. The strategy was never for Breakthrough's own teachers to deliver the curriculum across these states; rather, the pilot served as a proof of concept for governmental action. Consequently, in both Punjab and Odisha, it is the Social Studies teachers who are tasked with implementing this curriculum.

Ideally, I would have preferred these states to conduct a pilot before committing to a full-scale rollout. This isn’t about producing academic papers, but rather ensuring the program is refined and effective before widespread implementation. However, political realities often push for quicker scaling, as driven by chief ministers' agendas. We are assisting these states to some extent with monitoring and evaluation, although we do not anticipate the impact to be as pronounced as when specialized Breakthrough teachers were involved.

One challenge we face is that, unlike Breakthrough, which could recruit individuals specifically passionate about and skilled in leading discussions on gender equality, Social Studies teachers are not selected based on these criteria. This discrepancy could influence the effectiveness of the program. Moving forward, a potential compromise might involve identifying and training those teachers within the government system who are adept at leading discussions and are supportive of gender equality, to specialize in delivering this curriculum. This approach could help maintain the program's integrity and impact as it is scaled up.

Broader message about dismantling restrictive gender norms

Taking a step back, my message about this as a broader opportunity relates to dismantling and eroding restrictive gender norms in low and middle-income countries. While I focus primarily on India, which presents unique challenges even among these nations, the issue of gender inequality is prevalent across many low and middle-income countries. The emphasis on these countries is pertinent because, on average, gender norms tend to be more regressive in poorer regions. This situation is partly due to the shift toward service-oriented and knowledge-based jobs, which generally benefit women's participation in the workforce. Such economic transformations can catalyze broader social changes.

Moreover, there's a significant opportunity in these countries not only because the need for change is great but also because interventions can be more cost-effective. For example, the cost of public awareness campaigns, like renting space on bus shelters, is substantially lower in countries like India or Nigeria compared to a city like Boston. This economic advantage makes low and middle-income countries strategic locations for implementing and scaling gender equality interventions, maximizing the impact per dollar spent.

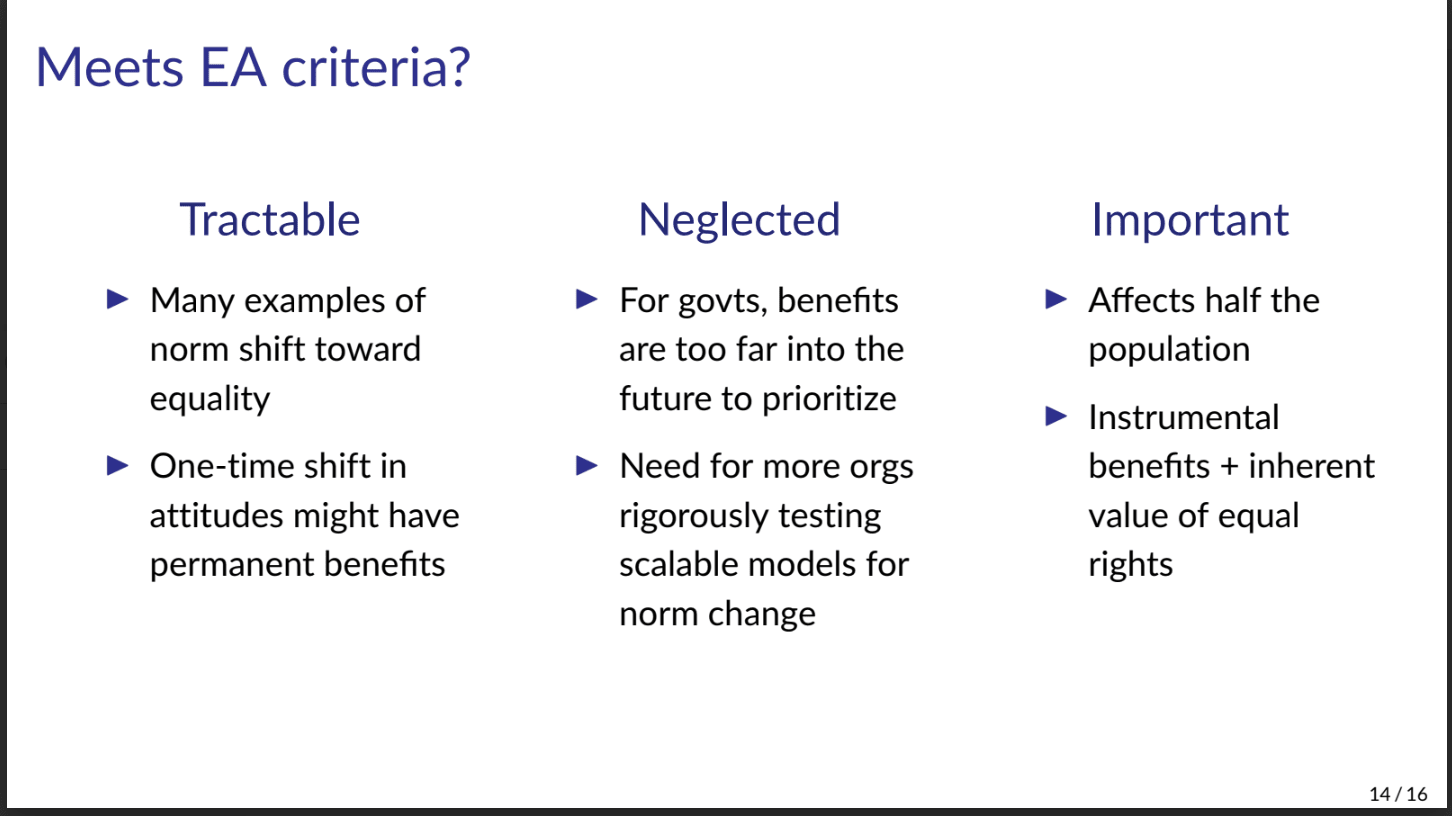

Tractability, neglectedness, and importance

Reflecting on whether this effort to shift gender norms is tractable, neglected, and important, I see it this way:

Tractability: The intervention by Breakthrough, though it was only version 1.0 and not something they've been doing for years, was successful. There are also many examples of norm shifts toward equality, such as the changes in attitudes toward same-sex marriage today that I never would have imagined as a kid. These have changed dramatically over my 50 years on this planet. I'm not sure if this should fall under tractable, but it's also a problem where you might have what our holy grail is—a one-time intervention that you might no longer need if you really get the norm shift.

Neglectedness: Norm change, as opposed to gender equality overall, I think is neglected in the sense that for the government, it's a long game, and it's not going to have a lot of political returns to try to innovate on how you change norms. So I think it's neglected in that sense.

Importance: It’s half the population. And there are instrumental benefits. But I personally put a lot of weight on things that are trying to bring about equal opportunities and equal rights. I’m well aware that this, at least within the global development and health part of the EA community, is not the prototypical example. It's not a one-size-fits-all technical fix. There are lots of nuances when trying to get people to adopt bed nets or vitamin A, so I don't want to oversimplify those, but this is going to be very culturally context-specific about how to change norms, involving lots of psychology about how humans are going to learn and change what they believe, etc. It's messier in that sense. And this is where, if I think about cause prioritization in terms of what I work on, I don’t try hard to put a dollar value on human rights. But if you believe in the inherent value of equal rights, it's going to strengthen cause prioritization for things that are about equal rights, whether that's about gender or race, etc..

Conclusion

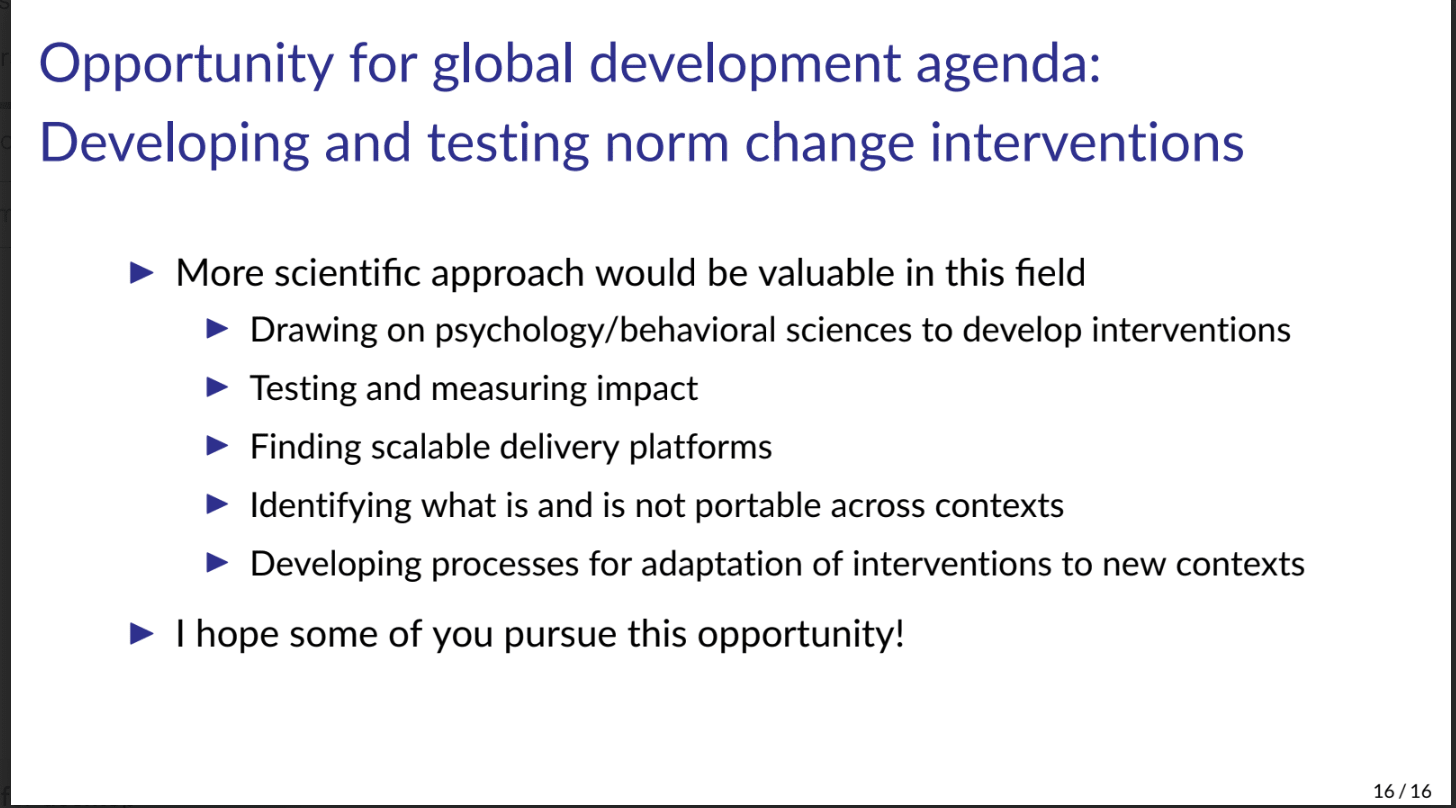

To conclude, the global development agenda presents a significant opportunity to delve into more complex, perhaps messier areas. There's a notable amount of risk-taking and uncertainty in other parts of the Effective Altruism (EA) community, particularly around norm changes in areas like animal welfare. I would love to see an increased focus on norm changes within the global development sector of EA, especially regarding gender, but also more broadly.

There’s a real chance here to adopt a more scientific approach. We can leverage psychology and behavioral sciences, drawing on evidence about how interventions should be developed, and methods for testing and measuring impact—this is my area of expertise. It’s crucial to consider not just developing an intervention, but also what makes a platform scalable and cost-effective. While things are context-specific, there are likely aspects of interventions that are conceptually portable.

Developing processes for these kinds of interventions is key. We need to consider how to transfer an intervention to a different context, how to test it, and how to adapt norm change interventions effectively. I hope that some of the people in this audience, who are at a stage in their career development or life where they can influence such decisions, decide to seize this opportunity, whether through direct involvement or by directing funding to these endeavors.

Q&A

Habiba: I'm kind of wondering, what do you think are the main features that are leading to these sticky norms being there in the first place? Like, does it tend to stick sort of in the kids’ minds? Like, does it tend to be the influence of their parents or their peers? Or sort of wider culture? Or is it? Is it like laws and institutions? Do you have a sense of, of what's driving the norms in the first place?

Seema: Yeah, I mean, it's probably a mix of factors, but certainly, families play a significant role in shaping perceptions, and it's also about what gets modeled in their daily lives. For example, when kids go out, they don't see many women working in restaurants and other public spaces, so it just seems normal that women aren't there. I think a lot of social norms function like an equilibrium. One reason I believe norm change is possible is that I don't think parents or community leaders actively spend a lot of time indoctrinating children with ideas like "this is why women don't work" or "this is why girls shouldn't continue in school." It’s not so much explicit moral education from the community or parents, but rather, that's where the kids pick it up from.

And then, of course, there might be instances where these ideas are amplified by peers. Additionally, societal norms do get codified into laws and institutions. There's evidence that changing laws or institutions can shift people's beliefs, but it’s likely that much of this stems predominantly from the older generation.

Habiba: Yeah, that makes sense. As we become more globally interconnected, to what extent can the norms change through exposure to media from other countries, where different norms prevail, and how might these influences impact local cultural norms?

Seema: Yes, I think that as people consume more media from other countries, they are increasingly exposed to and influenced by what's happening in other societies, and this can shift their views in a positive way. Although it's unclear exactly how many people are consuming US or European television shows and movies, there is some interesting research on soap operas. Soap operas typically feature fewer children per family because it's really hard to write a script with a large number of characters. For instance, in Brazil, where fertility rates were traditionally around six, the families in soap operas often had only three kids. Research shows that people who watched these soap operas came to view having fewer children as normal or modern, which actually contributed to lower fertility rates. So, yes, the media people consume can influence and modify societal norms.

Habiba: Wow. So child actor laws or being able to find good actors who can hit the mark and really affect fertility. . Considering the intervention's significant effects on boys and even their fathers, but the challenges girls face in changing their own circumstances until others around them also change their views, how can we go further in removing barriers so that girls themselves can fully capitalize on these opportunities? Do you think we might have to wait for another generation for this to happen?

Seema: Right. So, if you project this forward 50 years, you might envision a scenario where fathers, fathers-in-law, and husbands are all aligned in their thinking. At that point, if a girl is empowered, she won't be held back by others, but waiting that long is quite substantial. While I focus on norm change, there are immediate actions we can take. Enhancing safety and making educational institutions like colleges and schools more accessible can influence decisions at the margin, possibly encouraging someone to let their daughter pursue education. Additionally, there are policy measures that can complement a girl's desire to attend college, like governments offering conditional cash transfers to support girls attending school or college. Together, these strategies could act as substitutes for or complements to the deeper challenge of changing the entrenched attitudes of her parents and others.

Habiba: Okay, then we've had a few questions a bit more specifically on the research in India. So one question is: could you speak a bit more about the government's motivations and barriers for the intervention?

Seema: In this case, the government was interested in addressing the broader problem. Sometimes, governments are focused on very short-term metrics or specific issues they want to tackle quickly. This was a refreshing opportunity because it's not what I usually encounter; the government was genuinely open to testing this, and we didn't face much pushback. Typically, if we had expected the government to design and initiate the intervention from day one, there likely wouldn't have been much progress. Often, governments are constantly fighting fires, and such initiatives never rise to the top of the priority list. This scenario presented a nice example of how civil society can effectively collaborate with the government, acting as an innovation lab for a problem the government is interested in but isn't an immediate top priority. Additionally, we were initially concerned that there might be some resistance from parents or community leaders, fearing political backlash. Fortunately, that did not occur.

Habiba: That's great. And did the government have expectations of wanting to see results pay off in a shorter time frame? Or did they have things in mind that they were looking to see?

Seema: In this case, the state of Haryana did not adopt the program, which has both good and bad aspects. Sometimes, certain projects become a very high priority for the government, and then the pace of research that I and other development economists conduct might seem too slow due to the urgency to address problems before the next election or within a tight timeframe like a year. This pressure can sometimes be beneficial, reflecting a government's strong investment in finding solutions.

However, in this scenario, the program represented more of an option value for the government—whether it succeeded or failed, their operations and careers would likely continue with potential upsides. As a result, we didn't face much pressure from the government to deliver results within a specific timeframe. Then, when we began discussions with other state governments, we already had the results ready, providing instant gratification for them. We could immediately offer them evidence of an effective intervention. Breakthrough was ready to assist in training their teachers, and J-PAL was prepared to help monitor its effectiveness. Not every government official prioritizes such initiatives, so while not all states we spoke to were committed, two states decided to scale up the program.

Habiba: Did you have any practical lessons from the experience of scaling up the program in those two states? Would you change your approach if you had a chance to do it again?

Seema: Yeah, and I think that J-PAL has built up an amazing team, especially in India, where they have really deep relationships with governments. So this was not a fly-in, fly-out case, or something where I could just go and give one presentation. It wasn't about presenting results. It was about starting a partnership focused on evidence, RCTs, and capacity building. This involved talking to a bunch of civil servants, some of whom would turnover, requiring us to restart the relationship with their successors, and so on.

For me, the key takeaway is the benefit of investing in building non-transactional relationships with government partners where you become a thought partner. At the beginning of this project, it wasn't about us going in and pitching, "Hey, we want to do this, do you want to partner with us?" Nor was it the government coming to us saying, "Hey, we're about to roll this out, can you evaluate it?" It was more like, "Hey, we have this problem. Do you want to help us think about how to redesign and test it?" It was an open conversation. That's a real luxury for me as a researcher, and I'm really building on something that J-PAL has established—this trust with government partners.

Habiba: There were a couple of questions more specifically about some of the results. So first, I just wanted to double-check that the persistent results you mentioned were really compared against the control group still, even after many years? That seems astonishing to me that it persisted for, like, five years after what was presumably quite a short intervention.

Seema: Yeah, I wouldn't necessarily have guessed we would see this persistence either. On one hand, it was short, just 27 hours, but on the other hand, it probably represented a 2700% increase in the amount of time they'd explicitly spent thinking about gender equality. So, it's all post-hoc guessing, but if kids spend some time really contemplating their views on whether women should work, and at such a formative age they come to support women's employment, I can see that sticking. We all have certain moral views—like stances on the death penalty or gun control—that we probably form at some point and then tend to stick with. I think this might have been a time when kids first formed these views, and then they just persisted. That’s my guess, but I'm not sure.

Habiba: That’s super interesting. Did you notice any variations in the results based on socioeconomic factors, or depending on the different types of areas where the intervention was implemented? Were any such patterns evident in the results as well?

Seema: Yes, we tested for heterogeneity across various subgroups. The area we studied is predominantly Hindu, with noticeable variations in economic status among families. One uncertainty we had was whether the intervention would be more effective for kids from conservative families—perhaps because there's more room for improvement—or the opposite. There was a concern that conservative parents might simply suppress any new ideas introduced by the intervention. We wondered if the intervention might actually prove more successful in families that were already somewhat supportive of gender equality.

Interestingly, we observed that the results were similar across different subgroups, which might indicate that both dynamics are at play. For some individuals, the effect of overturning conservative views might dominate, while for others, the presence of supportive elements in their upbringing could be more influential.

Additionally, I had a hypothesis that the intervention might have less impact on the eldest son in families, as he arguably has the most to lose from changes to the status quo among boys. However, we didn’t find any evidence to support this hypothesis.

Habiba: Considering the broader context of prioritizing gender equality compared to other areas, how neglected do you think this space is? Gender equality is a focal point internationally, notably one of the Sustainable Development Goals, and there is also UN Women. It seems like there are already some interventions in this area. Does it still feel like the focus on norms within gender equality is more neglected?

Seema: Yes, I think the idea of neglectedness in this context is interesting. When considering whether gender equality is neglected, I wouldn't argue that there is a lack of funding or attention in the global development sector toward gender issues per se. Many people are working on gender equality, and there are significant resources allocated to it. However, I believe the neglected aspect is specifically the approach taken towards norm change as opposed to other strategies.

Wearing my J-PAL gender chair hat, I attend many convenings with NGOs and professionals working on gender issues. My background in engineering and physics shapes my thinking to be linear and evidence-based, and although not all economists think alike, this analytical approach does influence how I view interventions. In these settings, it becomes apparent that while the topic of gender equality is well-covered, the development, testing, and scaling of interventions, and specifically aimed at changing norms, are less emphasized.

Therefore, I would say that what's neglected isn't the topic of gender equality itself but rather the specific focus on effective, evidence-based interventions for norm change. This is the area where there seems to be room for more focused and impactful work.

Habiba: Like the scientific approach? Yeah, and then I guess, on the other side, in terms of the current trends, do you see how things are changing, especially with economic development, as developing countries become wealthier and more prosperous? Is this impacting gender attitudes somewhat naturally? And how might this compare to other interventions in the global development space? Are these changes heading in a positive or negative direction?

Seema: Well, my research focuses on gender and the environment, both areas where economic development isn't naturally solving the issues, and taking a laissez-faire approach doesn't seem to be working. That's why I started with the graph of the skewed sex ratio, because economic development doesn't seem to be solving that. I think, in many ways, economic development does help women, as I alluded to at one point, which involves the structural transformation from jobs like agriculture—where physical strength often means higher economic returns for men—towards more brain-based jobs where men and women are on equal footing. This shift means that families are leaving money on the table if women aren't working, and they're going to realize they should educate their daughters and encourage them to work. For instance, the shift towards call centers in India is beneficial for women, as they are likely to occupy these jobs.

In that sense, economic development is helping women. However, there are exceptions and cases where, despite pragmatic reasons for giving women more freedom, some norms persist, like the preference for sons. I don't have a deep theory about why some things change and others don't, but there's plenty of evidence of norms that may have evolved for practical economic reasons in the absence of a social safety net. In an agricultural society, sons were seen as the ones who could provide care, so they were highly valued. I always say, I think older people would rather be cared for by their daughter than their daughter-in-law if you really think about it. Elderly care involves more than just money. But now, it seems like the norm has taken on a life of its own.

So, economic development generally benefits women. Norms might originally form for economic reasons, but they don't necessarily adapt quickly as the economic environment changes. Instead, they solidify into what people perceive as right or wrong, becoming more akin to matters of morality, religion, or personal philosophy than pragmatic considerations.

Habiba: Yeah, okay. And then, I guess to wrap us up and bring us back to prioritization, when contrasting an intervention like this with others such as insecticide-treated malaria nets or vitamin A supplementation, I think some differences might be in how diffuse the benefits are with this type of intervention and perhaps how difficult it is to quantify the benefits, like measuring how it cashes out in terms of lives improved or lives saved. So, do you have a sense, from this economics mindset, of how we can compare the value of an intervention like this to others and determine whether this is something we should focus more of our time and attention on?

Seema: I mean, you can delve deeply and consider the instrumental benefits. For instance, you could design a study to measure spillovers on siblings, try to quantify spillovers on peers, just like many cost-benefit analyses that come with large standard errors or a ton of uncertainty, similar to fields like AI risk or biosecurity. As you try to extrapolate, uncertainty increases, but you can certainly attempt to quantify those effects. You could consider the economic impact of women working and what that would contribute to GDP. For the next generation, you might have to speculate, say, if we think we have a 0.1 standard deviation effect on attitudes, maybe that translates into a 0.05 standard deviation change in sex selection. I could do all of that exercise.

You could certainly attempt this, although I haven't tried to do so, partly because I think I sort of resist it, coming back to my inherent value of rights. When I think about this, and from work where you try to ask people—like women in India who might say they don't want access to money or rights—there's a real challenge in trying to elicit from people how much they value rights in the moment. If I thought about practical ways to value a woman's freedom to work if she chose to, even if she opts not to, I think that's pretty important, and I would have a lot of trouble putting a numerical value on it, or I kind of resist the push to do that.

I realize that ultimately, many people want to compare this to that, but there's so much uncertainty in many of the calculations we do anyway that ultimately, your own moral intuitions or even just what you're personally drawn to can be the tiebreaker in many of these cases. And, you know, for me, I think you can perform the cost-benefit analyses and the utilitarian calculation of some of the economic benefits, but I also think that I move away from a strictly utilitarian way of thinking about it in my own choice to work on this topic.

Can you tell us about how strongly changes in gender equality predict changes in measures of human wellbeing?

I understand what you're after, but I haven't seen a tidy way of converting improvements in gender equality to an all-up measure of well-being or income. That's partly for the reasons that David T states that gender equality is multi-faceted, plus if downstream benefits materialize gradually, they are hard to empirically isolate and quantify. In addition, promoting equality isn't just about the instrumental benefits like better use of human talent --> higher GDP, but also equality of opportunity being valuable per se, even if not exercised. I think if you tried to use standard methods to put a dollar value on rights, e.g., elicited women's WTP for equal rights, you wouldn't get a very informative answer. If someone asked me how much I value my right to free speech or freedom of religion, I would have nothing to anchor my answer and suspect it would be mostly noise. In addition, preferences adapt to circumstances. In some of my other work in India (see last paragraph of section 4.3), many women with extremely limited financial say in their household said they didn't want any more say than they had, and that men should control those decisions. I'm skeptical of taking that response at face value and concluding that increasing women's very low agency would not be welfare-improving for them.

That's going to be difficult to untangle, because improvements to some aspects like educational opportunities and shifts in generational attitudes take time to pay dividends and the causality plausibly runs both ways. Half the population is offered direct wellbeing improvements and the overall economic impact of education increased workforce participation is generally positive, but also countries most successful in tackling gender inequality tend to be ones that have already experienced positive trends in their development.

And also, of course, because there are a lot of different measures of gender equality and human wellbeing.

Countries which already have higher gender equality tend to do a lot better in HDI indicators and somewhat better in subjective wellbeing indicators, but there are obviously many other factors at play.

For people interested in this topic, I've found Alice Evans' writing interesting.

Executive summary: Dismantling restrictive gender norms in low-income countries through educational interventions is a promising and neglected opportunity to advance gender equality and women's rights.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

I realise this is not central to the post since by the sound of it you ended up not working on this, but what is this about? Who gets paid financial incentives when? How does this end up paying people to have daughters?

Several Indian states have policies that offer payments to families that have daughters, sometimes restricting it to below-poverty-line families. Sometimes the ongoing payments are conditional on being in school, not getting married early, etc. It looks like the Haryana policy no longer requires sterilization, but it used to. Here's an excerpt from a paper on the previous version, Devi Rupak:

"In light of these trends, Devirupak seeks to promote a one-child norm and to decrease the sex ratio at birth. It provides monthly benefits, for a period of 20 years, to couples who become sterilized after having one child (of either sex), or two girls (and no boy). The incentive offered to parents of one girl is larger than the amount that parents of one boy or two girls receive. Couples who remain childless, have a boy and a girl, or have more than two children receive nothing."

(That policy had dual goals of reducing fertility and improving the skewed sex ratio and ended up making the sex ratio more male-skewed. That part was just bad design and is fixable. But even if fixed, I don't love this approach to the problem.)