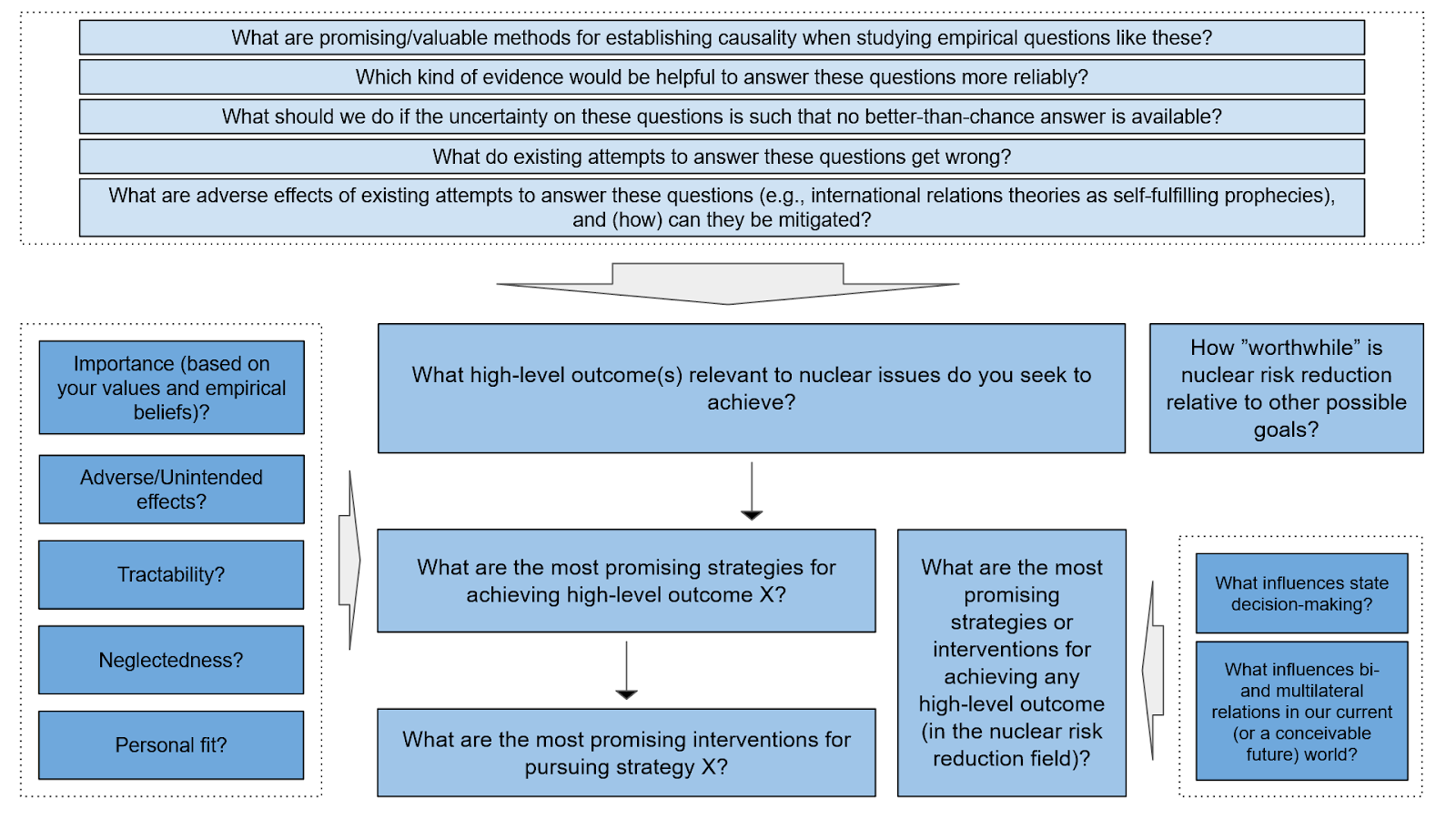

This is my attempt to give an overview of debates and arguments relevant to the question of how to mitigate nuclear risks effectively. I list a number of crucial questions that I think need to be answered by anyone (individual or group) seeking to find their role as a contributor to nuclear risk mitigation efforts. I give a high-level overview of the cruxes in Figure 1:

These questions are based on my moderately extensive engagement with the nuclear risk field[1]; they are likely not exhaustive and might well be phrased in a less-than-optimal way — I thus welcome any feedback for how to improve the list found below. I hope that this list can help people (and groups) reflect on the cause of nuclear risk reduction by highlighting relevant considerations and structuring the large amount of thinking that has gone into the topic already. I do not provide definitive answers to the questions listed, but try to outline competing responses to each question and flesh out my own current position on some of them in separate posts/write-ups (linked to below).

The post consists of the following sections:

- Setting the stage: some background on my CERI research project

- Main body: list of cruxes in the nuclear risk debate

- Substantive cruxes: questions to determine which nuclear risks to work on and how to do so

- Sub-cruxes: questions to help tackle the cruxes above

- Meta-level cruxes: methodological and epistemological questions

- Links and references

Setting the stage

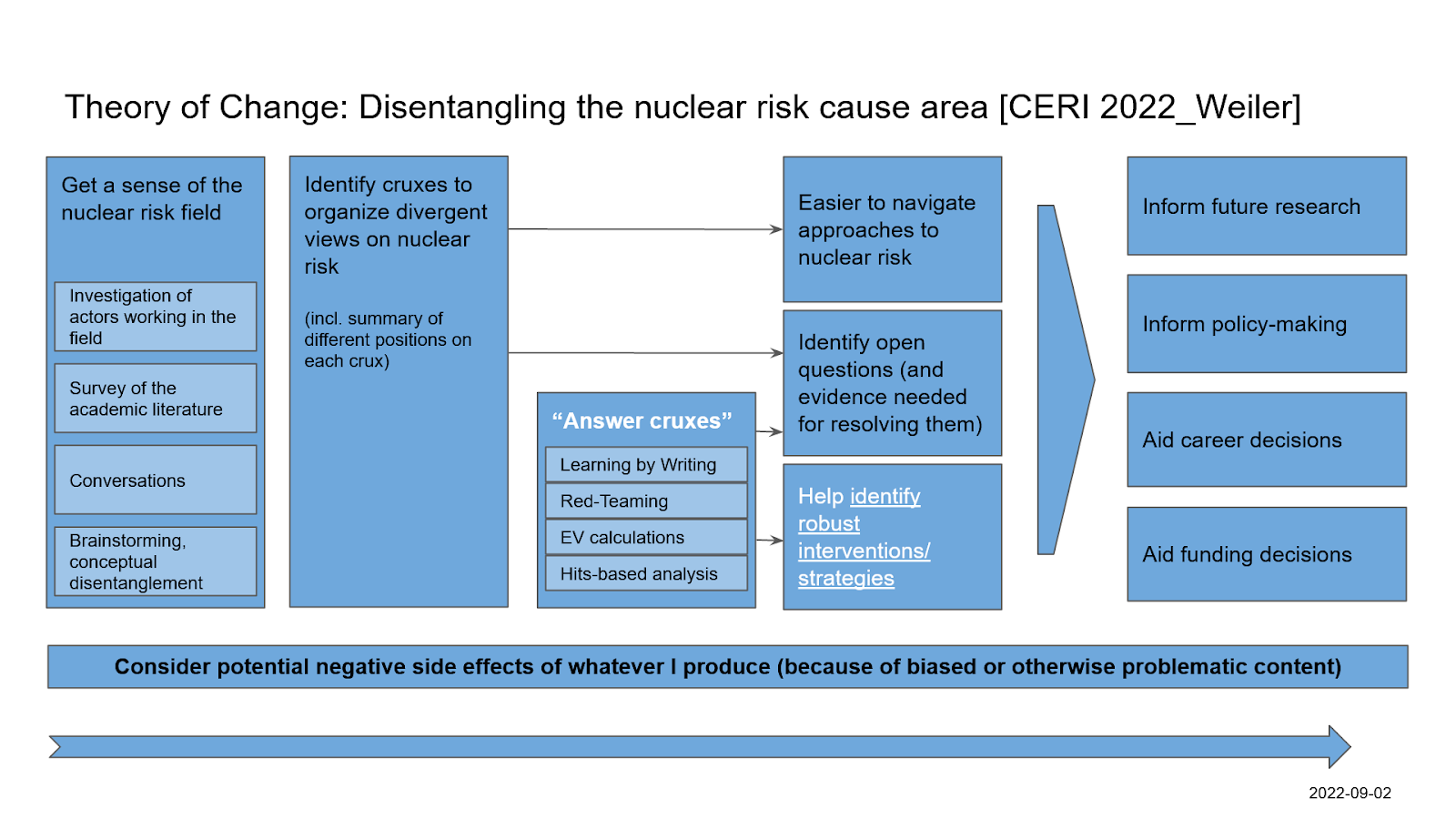

For a couple of months, I have been engaged in an effort to disentangle the nuclear risk cause area, i.e., to figure out which specific risks it encompasses and to get a sense for what can and should be done about these risks. I took several stabs at the problem, and this is my latest attempt to make progress on this disentanglement goal.

My previous attempts to disentangle nuclear risk

While I had some exposure to nuclear affairs during my studies of global politics at uni (i.e., at least since 2018) and have been reading about the topic throughout the last few years, I’ve been engaging with the topic more seriously only since the beginning of this year (2022), when I did a part-time research fellowship in which I decided to focus on nuclear risks. For that fellowship, I started by brainstorming my thoughts and uncertainties about nuclear risk as a problem area that I might want to work on (resulting in a list of questions and my preliminary thoughts on them), did a limited survey of the academic literature on different intellectual approaches to the topic of nuclear weapons, and conducted a small-scale empirical investigation into how three different non-profits in the nuclear risk field (the Nuclear Threat Initiative, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, and the RAND Corporation) conceptualize and justify their work on nuclear risk (resulting in a sketch of the theory of change[2]. of each organization, constructed based on the information they provide on their websites).

During ten weeks over this summer (Jul-Sep 2022), my participation in the Cambridge Existential Risk Initiative — a full-time, paid and mentored research fellowship — has allowed me to dedicate more time to this project and to test out a few more approaches to understanding the nuclear risk field. I spent around three weeks with the goal of compiling a list of organizations working on nuclear risk issues, collecting information on their self-described theory of change, and categorizing the organizations in a broad typology of “approaches to nuclear risk mitigation”. While I learned quite a bit about different ways of thinking about (and working on) nuclear affairs in that process, I ended up deciding against pursuing this specific project for the rest of the summer fellowship, because I got the sense that it wasn’t an optimal approach for obtaining a better understanding of the nuclear risk reduction field[3].

After some time spent trying to construct a network-like graph to interlink different possible goals for nuclear risk reduction work (possibly similar to attempts in the field of artificial intelligence research, see Manheim and Englander 2021 (AI Alignment Forum), MMMaas 2022 (EA Forum), and Christiano 2020 (EAG talk)), reading widely and reconsidering my goal and thoughts for how to get there, I have now arrived at the question-focused approach presented in this document (justification follows below).

What others have done

Attempts to introduce and give an overview of debates and different views on nuclear weapons are surprisingly hard to find (or I’m just bad at looking for them; please do comment if you think I missed something obvious that renders my project obsolete/redundant). The closest I have come across in academic or popular publishing are

- empirical studies on the attitudes of the general population (e.g., see this special journal issue on “Images of Nuclear War”: Fiske et al 1983, or this study of predictors for attitudes towards deterrence and disarmament: Axelrod and Newton 1991),

- studies that trace the doctrine and policymaking debates in individual nuclear weapons states (e.g., Bajpai 2000 on different views regarding the acquisition of nuclear weapons in India, or Lackey 1987 on the debate about the value and costs of nuclear weapons in the United States) or in other countries (e.g., Leah and Lyon 2010 who analyze the debate in Australia), and

- reports that outline one or a small set of strategies (e.g., Wan 2019, a recent UNIDIR investigation which uses different scenarios that could lead to nuclear war to construct a framework for thinking about risk reduction), or analyses that seek to evaluate past attempts to reduce nuclear risk (e.g., the “Nuclear Challenges Big Bet: 2020 Evaluation Report” commissioned by the MacArthur Foundation (Gienapp et al. 2021)).

While these works give some insights into different efforts for how to work on nuclear risk reduction, they don’t aim for a comprehensive overview of existing ideas (instead focusing on different subsets thereof). I thus believe and argue that, in the traditional nuclear studies field, there is a serious lack of thorough and accessible resources for managing, organizing and sharing/diffusing existing knowledge, understanding and arguments.

Within the effective altruism community, there are a number of write-ups introducing the nuclear risk problem area and giving some tentative takes on how to address the issue:

- OpenPhil produced a shallow investigation on nuclear weapons policy in 2015 with a section specifically on “What are possible interventions?” (OpenPhilanthropy 2015).

- 80,000 Hours has a problem profile on the topic with an extensive section on “What can you do about this problem?” (Hilton and McIntyre 2022).

- There is a chapter on nuclear weapons in The Precipice (Ord 2020) with a high-level discussion on nuclear weapons’ contribution to existential risks and the value of working on this problem.

- Rethink Priorities has published a number of posts on the topic (see this series on the EA Forum: Aird 2021a).

- What might come closest to my aspirations for this disentanglement challenge are the following works by Michael Aird (a researcher at Rethink Priorities): a categorization of views on nuclear risks and what to do about them (Aird 2021b), and a shallow review of approaches to reducing risks from nuclear weapons (Aird 2022).

While these resources have been very helpful to me in generating ideas and spurring my intuitions, I didn’t think that they were quite the thing that I envisioned as a resource to organize and optimally draw from the existing knowledge base on nuclear issues (mainly because these write-ups do not contain a thorough overview of and engagement with the nuclear issues literature and mainstream debate).

In addition to the above, there are some (EA-aligned) research projects and methodological commentaries outside the nuclear risk field that resemble my goal and which I have drawn on for inspiration and methodological insight:

- Luke Muehlhauser’s “Tips for conducting worldview investigations” (Muehlhauser 2022) and Holden Karnofsky’s blog posts on “Wicked problems” (Karnofsky 2022b, Karnofsky 2022c, and also Karnofsky 2022a) as helpful for navigating the challenging and often confusing/frustrating task I set myself

- An EA Forum post on strategy research (Rozendal, Shovelain and Kristoffersson 2019) and another one proposing the concept of “epistemic maps” (Durland 2021) as sources for methodological ideas

- Attempts to disentangle and organize debates and thinking around the risks from artificial intelligence (Manheim and Englander 2021 (AI Alignment Forum), MMMaas 2022 (EA Forum), and Christiano 2020 (EAG talk)) as sources of inspiration and for emulation

Value proposition: Why focus on identifying cruxes?

My rationale for this project is as follows: Ever since the invention of the atomic bomb in the 1940s (and arguably even before that, if fictional and/or futuristic contributions to the literature are counted[4]), the consequences of that new weapon and the question of how to deal with these consequences have been explored in debates between academics, public intellectuals, elite decision-makers, civil society activists, and the public at large (for an analysis of this early debate, see Sylvest 2020). This means that there now exists a vast body of literature on nuclear weapons, which may contain some valuable insights to inform our present-day thinking but which can also easily confuse and overwhelm those that seek to learn from prior debates. I have the impression that there is little consensus in the literature on nuclear weapons about what the major risks are and even less about how those risks could possibly be mitigated[5]. As a result, people who want to learn from prior work on the topic need to engage with it in some depth, since there are no obvious insights or consensus views to simply adopt on the basis of trust in the academic community[6].

At the moment, however, I think that engaging with the literature effectively is very difficult: It seems impossible to read everything that has been written on the topic, and I don’t think there is an obvious structure or a straightforward procedure for identifying the most important strands/arguments/texts to get an overview and a good idea of what the core disagreements (and competing positions) are.

This is where my project comes in. My attempts to grapple with the nuclear risk field have led me to believe that a list of crucial questions can be used to break down the broader puzzle of “What can be done to mitigate nuclear risks?”. I hope that this will result in a useful means to structure the debate on nuclear issues and to highlight relevant considerations for deciding how to work on this problem. More concretely, I envision several ways in which the list of questions can be helpful:

- People or groups that want to contribute to risk reduction efforts (through their own work or financial support) can go through the questions, figure out their own current best guess at an answer to each, and use that to choose the specific actions they think are worthwhile.

- People or groups that want to improve their understanding of nuclear issues (and want to contribute to ongoing intellectual debates) can use the questions as an organizing device to navigate the existing literature/debate.

- The list is also meant to highlight open questions, uncertainties, and holes in our current evidence base, and may thus be a basis for future research aimed at increasing/improving our actual knowledge regarding the effectiveness and value of different nuclear risk reduction efforts.

The cruxes of nuclear risk reduction work as I currently perceive them

Figure 1 (see above) gives a high-level overview of the relevant questions to address when trying to figure out how to work on nuclear risk reduction effectively (and whether to work on it at all). It contains a few substantive questions (located towards the middle part of the figure), answers to which can directly inform the kind of work an individual or group chooses to take on. Addressing these cruxes is helped by engagement with a number of meta questions (located in the top of the figure) and sub-questions, which break down the broad puzzle and thus hopefully make finding robust answers easier.

Below, I first address the substantive cruxes, listing conceivable answers, sub-questions to help tackle the broader puzzles, and my tentative position on each crux. I then turn to the meta-level question and briefly explain why I believe engagement with each of them to be vital if nuclear risk reduction efforts are to be effective.

Substantive cruxes

There is a sense in which the structure I settled on for this list of cruxes works in linear progression, starting with the question of whether and how much to care about nuclear risk overall and then successively moving from considerations about the desired high-level outcomes/goals, over intermediate goals/strategies, to specific interventions to pursue. However, the relationship between the different substantive cruxes is not entirely linear and one-directional once you take a closer look: questions about promising strategies and interventions feed back into higher-level cruxes, because the value of working on a high-level goal is partially determined by the tractability of such work and that tractability depends on how promising different concrete strategies and interventions are. In other words: If it turned out that the best strategies for achieving a certain high-level goal are not very promising, then that would be a significant argument in favor of deprioritizing the goal in question.

I believe, and hope, that the succession of substantive questions can aid individuals and groups in spelling out what they care about and why they decide to take some actions over others. I also hope that the cruxes help structure disagreements between different people working on nuclear risks, and that this structure can be an instrument for resolving disagreements, or at least misunderstandings, to some extent.

In this section, I give my (non-exhaustive) summary of possible views to take on each of these substantive cruxes and spell out my own tentative stance. The cruxes can be broken down into sub-questions; some of these are general and can be applied to each crux (listed in a separate section below), others are more concrete and tailored to a specific crux, likely to emerge only in the process of tackling the crux in-depth.

How ”worthwhile” is nuclear risk reduction relative to other possible goals?

This question is very much inspired by reasoning around cause prioritization prevalent within the effective altruism community, well-summarized on the Global Priorities Institute’s About page (GPI n.d.): “There are many problems in the world. Because resources are scarce, it is impossible to solve them all. An actor seeking to improve the world as much as possible therefore needs to prioritise, both among the problems themselves and (relatedly) among means for tackling them.”

Possible answers: In general, answers to this crux can fall on a continuum anywhere between “not worthwhile at all” to “more worthwhile than any other possible goal”, and can be given for an individual, a group, or for “humanity overall”. Addressing this crux requires taking a stance (implicitly or explicitly) on normative and empirical questions, since it is necessary to know/define your values as well as your beliefs for how these values can be realized/furthered before being able to evaluate different goals in terms of how worthwhile they are.

I am aware of little in-depth engagement with the question from the “traditional nuclear risk field” (i.e., governments, multilateral organizations, NGOs, academia), members of which tend to take the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons use as sufficient justification for their work and usually don’t compare nuclear risk reduction to other possible cause areas. In the effective altruism community, on the other hand, the crux has been tackled by some analysts in recent years (see Rethink Priorities’ series of posts on the EA Forum (Aird 2021a) 80,000 Hours’ problem profile (Hilton and McIntyre 2022), and Toby Ord’s (2020) assessment of nuclear risk in The Precipice). These analyses look at the topic primarily from a longtermist perspective[7] and they suggest, broadly speaking, that it is unclear whether risks from nuclear weapons should be amongst the most highly prioritized cause areas for the effective altruism community, but that they are sufficiently important, tractable, and neglected to be a worthwhile focus area for some people and organizations in the community[8].

For readers who like to think about cause prioritization with EA-esque frameworks in mind (using the importance-tractability-neglectedness framework, the longtermist-neartermist distinction, or expected-value reasoning generally) and who would like to engage with this crux by themselves rather than deferring to the sources I link to above, I think that the following propositions about nuclear weapons and their significance could be helpful (accepting either of them could form the basis for thinking about how to prioritize between nuclear risk reduction and other cause areas)[9]:

- Nuclear weapons pose an existential risk (of varying probability).

- Nuclear weapons pose a direct extinction risk (through nuclear winter).

- Nuclear weapons pose a direct risk to curtail humanity's potential in a different way (e.g., by enabling the rise of a global totalitarian regime).

- Nuclear war is an existential risk factor, i.e. would render the world more vulnerable to other risks.

- Nuclear war is a non-existential global catastrophic risk, and working on it is competitive with working on leading neartermist interventions.

- Nuclear war is a non-existential global catastrophic risk, and working on it is not competitive with working on leading neartermist interventions (it is more akin to earthquakes or smaller-magnitude volcanic eruptions).

My tentative answer: I must admit that I’m quite confused about the methodological and normative questions surrounding “cause prioritization” generally and more clarity on that seems a prerequisite for addressing this crux more thoroughly. I have a fairly strong intuitive (or common-sense-backed?) sense that working on this problem is important and that it is worth my time and effort to at least try and see whether I might be well-suited for contributing something to this cause area. This is partly based on the fact that I can imagine several ways in which nuclear weapons could feature prominently in global catastrophic, and possibly in x-risk, events, and partly based on deference to the large number of prominent and seemingly smart individuals who consider the danger of nuclear weapons massively important to address (for one example out of many, see this commentary on the website of the Union of Concerned Scientists (n.d.), and for an example from within the effective altruism community, see Toby Ord’s chapter on nuclear weapons in The Precipice), but is not the conclusion of a sophisticated personal cause prioritization research project on my side.

What high-level outcome(s) (relevant to nuclear issues) do you seek to achieve?

Possible answers: Once again, the answer to this question relies on certain normative as well as empirical beliefs, none of which I will expand on here. Instead, I offer a list of conceivable high-level outcomes, without specifying the premises one would need to accept to endorse or prioritize each one:

- Prevent nuclear winter, by preventing the worst kinds of nuclear war (in terms of numbers or types of weapons used, or targets chosen)

- Prevent nuclear war of any kind

- Prepare for the consequences of nuclear war (ecological, i.e. nuclear winter, political, social, economic, cultural/normative, technological)

- Prevent (or end) the use of nuclear weapons for (totalitarian) oppression (by a world state, by a small group of nuclear weapons states, by terrorists or rogue actors)

- Ensure that country X would win if it came to nuclear war

- Reduce “nuclear injustice”

- Injustice in the international system as a result of the unequal distribution of power between nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapons states

- Injustice suffered by victims of nuclear war, or of the production of nuclear weapons (esp. through weapons tests)

- Injustice suffered by future generations that will not come to exist or will have substantially worse lives due to present-day nuclear policies

- Deter (conventional) war through the non-military use of nuclear weapons (possession of nuclear weapons as a deterrent and “force for peace”)

- …

My tentative answer: In a separate post, I explain why I am moderately confident at the moment that the priority of nuclear risk reduction for myself and the large majority of others working on the topic should be “reducing the probability of any kind of nuclear war”, rather than reducing the probability of only specific kinds of nuclear war or preparing for the consequences of nuclear war. I have not looked at and don’t have a strong opinion about the importance of other conceivable high-level outcomes relative to those three goals addressed in my write-up[10]. To address this question, I did not conduct a sophisticated academic investigation, nor did I go through and carefully answer the meta-level questions listed above. Instead, my provisional, but nonetheless moderately confident stance is based on a few weeks worth of dedicated reading, thinking and talking about the crux, and is informed by the intuitions I developed through my study of nuclear issues throughout the last few years.

What are the best strategies for achieving high-level outcome X?

Addressing this question in the abstract seems not very promising since the answer will likely differ depending on the specific high-level outcome you look at. In the end, I think it is necessary to pick out whichever high-level outcome strikes you as (most) relevant and tackle the more specific question of how to achieve that. In a separate write-up, I take a stab at one of these more specific questions: What are the most promising strategies for reducing the probability of nuclear war?, in which I seek to give a comprehensive (if not exhaustive) overview of the answers that have been proposed by others and then break up the broad puzzle into more specific subquestions to evaluate the validity of different answers.

What are the most promising interventions for pursuing strategy X?

In my investigations during this fellowship, I found it useful to differentiate between broad strategies and specific interventions when thinking about approaches for achieving a given high-level outcome (quite similar to the differentiation between strategy and tactical research proposed in this EA Forum post: Rozendal, Shovelain and Kristoffersson 2019).

For instance, my deep-dive into the question of how best to reduce the probability of nuclear war led me to identify five broad strategies: complete and permanent nuclear disarmament, stable & effective deterrence, norms against nuclear use (in its strongest form, the nuclear taboo), changes to the security environment (of nuclear-weapons states), and measures to enhance nuclear safety & security (prevent accidents, technological glitches, theft). Answering “What are the best strategies for preventing nuclear war?” by opting for one or several of these approaches then leads straightforwardly to follow-up cruxes that ask about the best intervention(s) for pursuing the chosen approach(es). It is not enough, for instance, to say that permanent and complete nuclear disarmament seems the most promising strategy for reducing the probability of nuclear war; in order to come up with an actionable plan for how to work on nuclear risk reduction, you also need some idea about how disarmament can be achieved.

Sub-questions: Tackling substantive cruxes by breaking them up

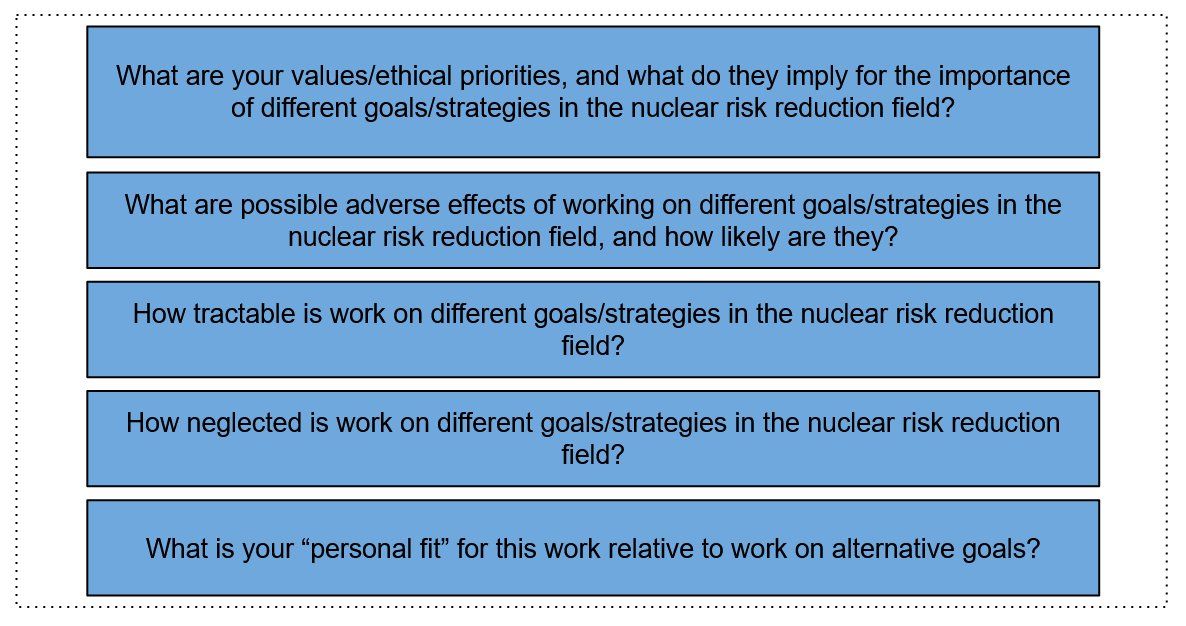

Prioritization questions

Since the point of this overview is to give people and groups an aid for deciding which problems and interventions to focus on, heuristics for prioritization seem obviously useful. I follow common EA practice here and suggest the importance-tractability-neglectedness (ITN) framework[11], as well as a personal fit heuristic (Todd 2021) to come up with a rough ranking of which problems to work on. In addition, I claim that consideration should be given to possible adverse effects (risks) of working on different goals, strategies and interventions. These decision criteria and their relevance to the nuclear risk cause area are described in a bit more detail in this section. The questions cannot be answered in the abstract; rather they are relevant when applied to any one of the substantive cruxes outlined above.

What are your values/ethical priorities, and what do they imply for the importance of different goals, strategies and interventions in the nuclear risk reduction field, as well as for nuclear risk reduction as an overarching goal?

I imagine that this question will raise some eyebrows: Does it really make a significant difference whether a consequentialist or a deontologist is asked about the importance of nuclear weapons and the value of work to reduce the risks associated with them? Should this not be a priority across the majority of existing and conceivable ethical beliefs?

While most ethical approaches can generate arguments to justify/recommend nuclear risk reduction efforts, differentiating between them does matter when it comes to figuring out just how important the danger from nuclear weapons is relative to other problems. It also matters for deciding which specific aspects of that danger to focus on. I won’t give this an in-depth discussion (the time I have in the fellowship is limited, and I don’t understand the range of ethical views well enough to give a sophisticated elaboration even if I wanted to), but here’s an example to illustrate why and how values matter:

A suffering-focused utilitarian (Wikipedia 2021) is going to care about how many people are likely to be harmed by different kinds of nuclear war (as well as by other risks associated with nuclear weapons, such as the possibility of a global totalitarian regime in possession of these weapons), compare this to the amount of suffering caused by other problems, and then distribute resources for fighting different problems according to how much suffering they cause in expectation. Many proponents of the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons likely believe these questions and calculations to be besides the point, arguing that the nature of nuclear weapons and their role in today’s militaries is so fundamentally wrong that no accounting for the precise amount of suffering they cause in expectation is needed in order to decide that fighting for their abolition is worth the effort (e.g., compare ICAN’s commentary on the treaty (ICAN n.d.)). I would guess that a ranking of different problems is as irrelevant for this TPNW proponent as the fundamental moral character of nuclear weapons is to the suffering-focused utilitarian.

How tractable and neglected is work on different outcomes, strategies, or interventions?

Tractability and neglectedness are criteria taken from the ITN-framework for comparing different problems and the value of working on them (I discuss the third criterion, importance, in the previous section): “The tractability of a problem (also called its solvability) is the degree to which it is solvable by a given increase in the resources allocated to it” (EA Forum description); “The neglectedness of a problem (also called its uncrowdedness) is the amount of resources currently allocated to solving it” (EA Forum description). The basic idea is that a stock of resources will contribute more to solving a given problem if it is more tractable and/or more neglected (other things being equal), and that it is good for resources to have more rather than less (positive) impact. It follows from these assumptions that the tractability and neglectedness of two problems can serve as an input for deciding which of the two to work on.

What is your “personal fit” for working on different outcomes, strategies, or interventions?

It seems uncontroversial to say that decisions for how to approach nuclear risk reduction need to take into account not just characteristics of the different problems and interventions but also of the actors that seek to do the interventions[12]. In the words of Ben Todd from 80,000 Hours (2016): “There’s no point working on a problem if you can’t find any roles that are a good fit for you – you won’t be satisfied or have much impact.”

“Personal fit” in this case refers to a person (or group’s) interests, capabilities, knowledge/skills, resources (budget, network, credentials, etc), and constraints (e.g., a legal barrier to working in a certain country or position).

What are possible adverse effects of working on different outcomes, strategies or interventions, and how likely are they?

For many interventions in the nuclear risk reduction space, a convincing case can be made that there are substantial downside risks that warn against pursuing the interventions. These could be risks that materialize if the intervention fails (e.g., arms reduction efforts could actually lead to a more dangerous world, if they stop short of complete disarmament and make nuclear weapons states feel more vulnerable and more quick to escalate in times of crisis), it could be side effects (e.g., attempts to strengthen deterrence postures may lead to security dilemmas, or simply to a more hostile international environment, both of which make escalation and conflict more likely), or unforeseen outcomes (e.g., centralizing command over nuclear weapons in a global authority to prevent their use in inter-state war may end up empowering a global regime of totalitarian repression). It’s not obvious how strongly such potential adverse effects should weigh against an intervention, but it seems very intuitive that they should receive some consideration in the evaluation of different strategies for reducing nuclear risk.

Basic questions about global politics

I think there are some general questions about how global politics works that are relevant for all or most conceivable high-level outcomes, strategies, and interventions in the nuclear risk reduction field:

- What influences state[13] decision-making?[14]

- What influences bi- and multilateral relations in our current (or a conceivable future) world?[15]

- …

These questions are hard and there is some evidence to suggest that they are fairly intractable: they have decades- and sometimes centuries-long debates to their name, without the emergence of anything like a robust scholarly consensus[16], and there is no straightforward way to test different answers to these questions and to receive reliable or clear feedback on which hypothesized answer performs best. However, I believe that it’s worth thinking about whether there might be ways to improve the validity/robustness of our answers to these questions[17], and I encourage readers to address that challenge in the kind of thesis-long treatment that it deserves!

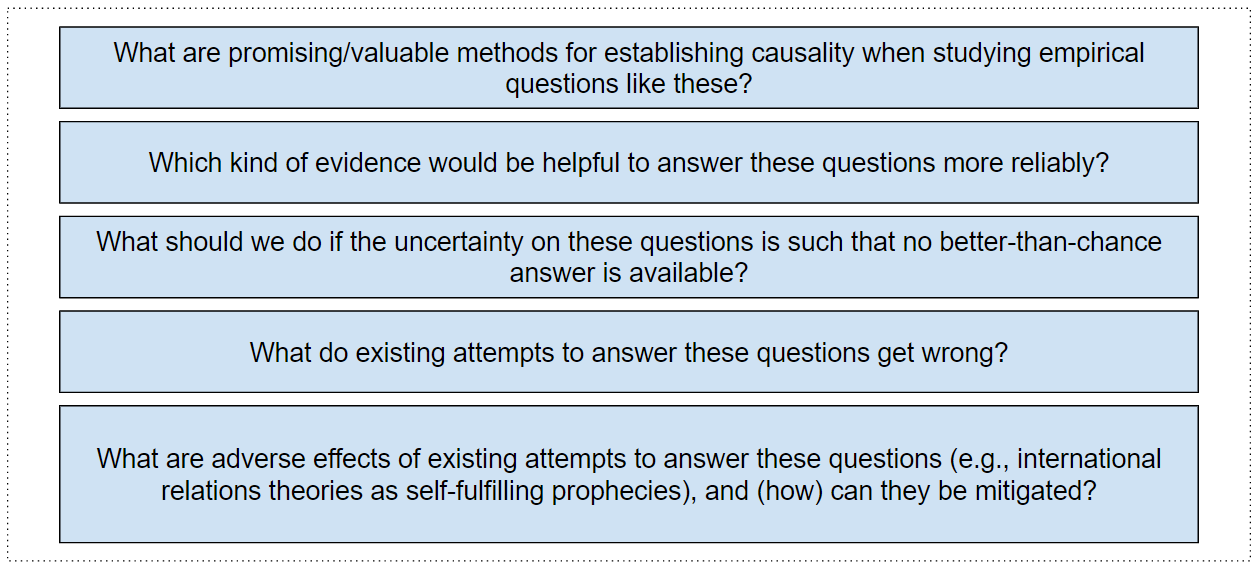

Meta-level cruxes: methodology and epistemology

Whether consciously or not, grappling with the cruxes I list requires taking a stance on methodological and epistemological conundrums. I believe that it is preferable if this is done explicitly rather than in an un- or poorly considered reliance on some unstated assumptions. Additionally, I hold out some hope for progress on the methodological and epistemological disputes at issue, which is a further reason to spell out (and subsequently try to address) these meta-level questions.

What are promising/valuable methods for establishing causality when studying social phenomena?

The relevance of understanding how to identify causal relationships can be illustrated by listing a few example questions that feed into evaluating different outcomes, strategies and interventions in the nuclear risk reduction space: How would international politics be affected by a conflict involving nuclear weapons? How would movement towards a more just/equal global (nuclear) order[18] affect the world’s ability to tackle catastrophic risks? What causes decision-makers to take escalatory steps in a crisis? What (if anything) is the effect of the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons on state leaders’ willingness to use nuclear weapons?

Which kind of evidence would be helpful to answer the substantive cruxes more reliably?

Insightful evidence to illuminate many of the relevant cruxes in the nuclear risk reduction field (and in political science more broadly) is hard to come by. So hard, in fact, that I developed doubts on whether evidence-based policymaking in this space is an option at all, which is the reason why I included the following question about what to do in the face of deep uncertainty in my list of cruxes. That being said, I believe that there could be value in a deep-dive into the crux of what kind of evidence is used in prominent arguments and proposals in the nuclear risk space and of how strong or robust the conclusions from that evidence are. Unfortunately, I didn’t really manage to address this puzzle during the summer fellowship and only have broad impressions and some scattered resources on possible answers to the question at this point.

What should we do if the uncertainty on empirical questions is such that no better-than-chance answer is available?

Efforts to tackle nuclear risks face enormous levels of uncertainty. Our understanding of the likely effects of different types of intervention to reduce nuclear risks is quite poor and, arguably, hard to improve because of the nature of the problem. We are faced by a multiplicity of possible causal influences and by multi-directionality/complexity of the relationship between variables, and we have to accept that no counterfactual world is available, that we are unable to conduct controlled experiments, and that we only have access to a relatively low number of relevant observations to perform natural experiments and statistical analyses on. All of this, I would argue, severely limits our ability to reduce uncertainty vis-a-vis questions such as “What kind of security environment makes nuclear war less likely?”, and “Are there viable interventions to significantly decrease the likelihood of a nuclear accident?”

I think it’s vitally important that we face the challenge of that empirical uncertainty and grapple with the question of what to do in the face of it - Are there ways to reliably reduce uncertainty to such an extent that policy recommendations based on empirical analyses become feasible? Or should the ideal of evidence-based policy be given up as not workable? How should decisions be made if the consequences of our actions are to a significant extent unknown and unknowable?[19]

What does existing scholarship on nuclear issues (and on global politics more generally) get wrong?

Questions in the nuclear risk space are hard, and straightforward answers, backed by a strong evidence base, don’t seem to be available. This makes it all the more important, in my opinion, to carefully scrutinize existing attempts to provide answers. The wealth of critical analysis which highlights systemic biases and distortions in the relevant literature (on international relations (Goh 2019), foreign policy (Yetiv 2013), security studies (Schweller 2007), as well as on nuclear weapons more specifically (Braut-Hegghammer 2019)) gives further impetus to this call for scrutiny and critical reflection. Such critical scholarship vis-a-vis existing arguments and policy recommendations may help avoid mistaken policy choices, may improve the epistemic quality of the debate on the topic, and may forestall overconfidence in both researchers/analysts and in policymakers.

What are the (adverse) effects of scholarship on nuclear issues, and what does that imply for how research should be conducted?

Reflectivist theories in the social sciences argue that academic research has significant effects on developments in the real world, including on political decision-making[20], and that researchers thus have a special responsibility in how they go about their work (which topics they choose, which perspectives they adopt and ignore, which methods they employ, etc.).

In the fields of international relations and security studies, which seem to be the academic disciplines most relevant to the study of nuclear risks, this issue has been raised, for instance, by Houghton 2009 (who describes how theories about global politics can turn into self-fulfilling or self-denying prophecies), by Ish-Shalom 2006 (who traces harmful attempts of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to encourage development abroad at least partly to reductionist academic modernization theories), and by Smith 2004 (who argues that the International Relations discipline employs and thus reinforces a narrow definition of violence, contributing to policies that ignore or even further certain forms of injustice and oppression, which in turn creates the conditions for terrorism and other forms of violent resistance).

I won’t provide well-defined guidelines for how (EA) nuclear risk researchers should behave in light of these arguments here, but I do think that it’s important for scholars to be aware of these arguments and to have spent some time thinking through what they imply for their own work.

Other pieces I wrote on this topic

- Disentanglement of nuclear security cause area_2022_Weiler: written prior to CERI, as part of a part-time and remote research fellowship in spring 2022)

- A case against focusing on tail-end nuclear war risks

- What are the most promising strategies for preventing nuclear war?

- List of useful resources for learning about nuclear risk reduction efforts: This is a work-in-progress; if I ever manage to compile a decent list of resources, I will insert a link here.

- How to decide and act in the face of deep uncertainty?: This is a work-in-progress; if I ever manage to bring my thoughts on this thorny question into a coherent write-up, I will insert a link here.

References

Atkinson, Carol. 2010. “Using nuclear weapons.” Review of International Studies, 36(4), 839-851. doi:10.1017/S0260210510001312.

Aird, Michael. 2021a. “Risks from Nuclear Weapons.” EA Forum (Series of Posts) (blog). June 9, 2021. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/KJNrGbt3JWcYeifLk.

———. 2021b. “Metaculus Presents: Forecasting Nuclear Risk with Rethink Priorities Researcher Michael Aird.” Online presentation and Q&A, Metaculus, October 20. https://youtu.be/z3BNer81wHM.

———. 2022. “[Public Version 26.03.22] Shallow Review of Approaches to Reducing Risks from Nuclear Weapons.” Shallow review (work in progress). GoogleDoc. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1uQgYUoN270weTRBqqLrCnEKLafq8Xq4ZPdYL0kPHROQ/edit?usp=embed_facebook.

Axelrod, Lawrence J., and James W. Newton. 1991. “Preventing Nuclear War: Beliefs and Attitudes as Predictors of Disarmist and Deterrentist Behavior1.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 21 (1): 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1991.tb00440.x.

Bajpai, Kanti. 2000. “India’s Nuclear Posture after Pokhran II.” International Studies 37 (4): 267–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881700037004001.

bean. 2022. “EA on Nuclear War and Expertise — EA Forum.” EA Forum (blog). August 28, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/bCB88GKeXTaxozr6y/ea-on-nuclear-war-and-expertise.

Braut-Hegghammer, Målfrid. 2019. “Proliferating Bias? American Political Science, Nuclear Weapons, and Global Security.” Journal of Global Security Studies 4 (3): 384–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz025.

Christiano, Paul. 2020. “Current Work in AI Alignment.” EA Global Talk, EA Forum, March 4. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/63stBTw3WAW6k45dY/paul-christiano-current-work-in-ai-alignment.

Durland, Harrison. 2021. “‘Epistemic Maps’ for AI Debates? (Or for Other Issues) — EA Forum.” EA Forum (blog). August 30, 2021. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/s33LLoR6vbwiyRpTm/epistemic-maps-for-ai-debates-or-for-other-issues.

EA Forum. n.d. “ITN Framework.” In Effective Altruism Forum. Centre for Effective Altruism. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/itn-framework.

———. n.d. “Longtermism.” In Effective Altruism Forum. Centre for Effective Altruism. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/longtermism.

———. n.d. “Neglectedness.” In Effective Altruism Forum. Centre for Effective Altruism. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/neglectedness.

———. n.d. “Theory of Change.” In Effective Altruism Forum. Centre for Effective Altruism. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/theory-of-change.

———. n.d. “Tractability.” In Effective Altruism Forum. Centre for Effective Altruism. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/tractability.

———. n.d. “Expected Value.” In Effective Altruism Forum. Centre for Effective Altruism. Accessed November 13, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/expected-value.

Fiske, Susan T., Baruch Fischhoff, and Michael A. Milburn. 1983. “Images of Nuclear War: An Introduction.” Journal of Social Issues 39 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1983.tb00126.x.

Gienapp, Anne, Alex Chew, Adele Harmer, Alex Ozkan, Chan, and Joy Drucker. 2020. “Nuclear Challenges Big Bet: 2020 Evaluation Report.” evaluation report commissioned by the MacArthur Foundation and written by ORS Impact. https://www.macfound.org/press/evaluation/nuclear-challenges-big-bet-2020-evaluation-report.

Goh, Evelyn. 2019. “US Dominance and American Bias in International Relations Scholarship: A View from the Outside.” Journal of Global Security Studies 4 (3): 402–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz029.

GPI. n.d. “About Us.” Homepage. Global Priorities Institute. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://globalprioritiesinstitute.org/about-us/.

Hilton, Benjamin, and Peter McIntyre. 2022. “Nuclear War” 80,000 Hours: Problem Profiles (blog). June 2022. https://80000hours.org/problem-profiles/nuclear-security/#top.

Houghton, David Patrick. 2009. “The Role of Self-Fulfilling and Self-Negating Prophecies in International Relations.” International Studies Review 11 (3): 552–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2486.2009.00873.x.

ICAN, (International Campaign to Ban Nuclear Weapons). n.d. “Why a Ban?” Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.icanw.org/why_a_ban.

Ish-Shalom, Piki. 2006. “Theory Gets Real, and the Case for a Normative Ethic: Rostow, Modernization Theory, and the Alliance for Progress.” International Studies Quarterly 50 (2): 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00403.x.

Karnofsky, Holden. 2022a. “Learning By Writing (Section: ’I Hope I Haven’t Made This Sound Fun or Easy’).” Cold Takes (blog). February 22, 2022. https://www.cold-takes.com/learning-by-writing/#i-hope-i-havent-made-this-sound-fun-or-easy.

———. 2022b. “The Wicked Problem Experience.” Cold Takes (blog). March 2, 2022. https://www.cold-takes.com/the-wicked-problem-experience/.

———. 2022c. “Useful Vices for Wicked Problems.” Cold Takes (blog). April 12, 2022. https://www.cold-takes.com/useful-vices-for-wicked-problems/.

Lackey, Douglas P. 1987. “The American Debate on Nuclear Weapons Policy: A Review of the Literature 1945-1985.” Analyse & Kritik 9 (1–2): 7–46. https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-1987-1-201.

Leah, Christine, and Rod Lyon. 2010. “Three Visions of the Bomb: Australian Thinking about Nuclear Weapons and Strategy.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 64 (4): 449–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2010.489994.

Manheim, David, and Aryeh Englander. 2021. “Modelling Transformative AI Risks (MTAIR) Project: Introduction.” AI Alignment Forum (blog). August 16, 2021. https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/qnA6paRwMky3Q6ktk/modelling-transformative-ai-risks-mtair-project-introduction.

McGlinchey, Stephen, Rosie Walters, and Christian Scheinpflug, eds. 2017. International Relations Theory. E-International Relations Publishing. https://www.e-ir.info/publication/international-relations-theory/.

MMMaas. 2022. “Strategic Perspectives on Long-Term AI Governance: Introduction.” EA Forum (blog). February 7, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/isTXkKprgHh5j8WQr/strategic-perspectives-on-long-term-ai-governance.

Muehlhauser, Luke (lukeprog). 2022. “Tips for Conducting Worldview Investigations.” EA Forum (blog). April 12, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/vcjLwqLDqNEmvewHY/tips-for-conducting-worldview-investigations.

“Negative Utilitarianism.” 2021. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Negative_utilitarianism&oldid=1053366101.

OpenPhilanthropy. 2015. “Nuclear Weapons Policy.” Shallow investigation. Open Philanthropy. https://www.openphilanthropy.org/research/nuclear-weapons-policy/.

Ord, Toby. 2020. The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Illustrated edition. New York: Hachette Books.

Rozendal, Siebe (SiebeRozendal), Justin (JustinShovelain) Shovelain, and David (David_Kristoffersson) Kristoffersson. 2019. “A Case for Strategy Research: What It Is and Why We Need More of It.” EA Forum (blog). June 20, 2019. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/oovy5XXdCL3TPwgLE/a-case-for-strategy-research-what-it-is-and-why-we-need-more.

Schweller, Randall L. 1996. “Neorealism’s Status‐quo Bias: What Security Dilemma?” Security Studies 5 (3): 90–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636419608429277.

Smith, Steve. 2004. “Singing Our World into Existence: International Relations Theory and September 11.” International Studies Quarterly 48 (3): 499–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.t01-1-00312.x.

Sylvest, Casper. 2020. “Conceptions of the Bomb in the Early Nuclear Age.” In Non-Nuclear Peace: Beyond the Nuclear Ban Treaty, edited by Tom Sauer, Jorg Kustermans, and Barbara Segaert, 11–37. Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26688-2_2.

Todd, Benjamin. 2017. “Which Global Problem Is Most Important to Work on? What the Evidence Says (Section: ’Your Personal Fit and Expertise’).” 80,000 Hours: Career Guide (blog). March 2017. https://80000hours.org/career-guide/most-pressing-problems/.

———. 2021. “Personal Fit: Why Being Good at Your Job Is Even More Important than People Think.” 80,000 Hours: Key Articles (blog). September 2021. https://80000hours.org/articles/personal-fit/.

USC, (Union of Concerned Scientists). n.d. “Nuclear Weapons.” Accessed October 9, 2022. https://www.ucsusa.org/nuclear-weapons.

Wan, Wilfred. 2019. “Nuclear Risk Reduction: A Framework for Analysis.” UNIDIR. https://unidir.org/publication/nuclear-risk-reduction-framework-analysis.

Wells, H. G. 2007. The World Set Free. Lulu.com.

Wiblin, Robert (Robert_Wiblin). 2022. “I’m Interviewing Sometimes EA Critic Jeffrey Lewis (AKA Arms Control Wonk) about What We Get Right and Wrong When It Comes to Nuclear Weapons and Nuclear Security. What Should I Ask Him?” EA Forum (blog). August 26, 2022. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/Ekiy3mooXsFurXqDp/i-m-interviewing-sometimes-ea-critic-jeffrey-lewis-aka-arms.

Yetiv, Steve A. 2013. National Security Through a Cockeyed Lens: How Cognitive Bias Impacts U.S. Foreign Policy. JHU Press.

- ^

I took a class on nuclear politics for my undergraduate degree, worked on the topic as a part-time research fellow this spring (see Previous attempts to “disentangle nuclear risk”), learned about the topic on the side through books, articles, podcasts and the like throughout the last few years, and have spent ten weeks this summer as a full-time CERI research fellow to develop this overview of the field.

- ^

“A theory of change is a set of hypotheses about how a project—such as an intervention, an organization, or a movement—will accomplish its goals” (definition given on the EA Forum’s topic page for Theory of Change).

- ^

A few things that probably caused/justify this sense:

(-) Disagreements on nuclear risk seem too multi-dimensional to fit different ideas into a limited number of broad ideal types (I tried to do this and came away with four types that seemed a bit shallow and for which I couldn’t articulate and justify very clearly why I chose to carve up the nuclear debate in the way that I did).

(-) The non-profit organizations I looked at did not seem to really cover the range of ideas on nuclear risk that I perceived in the academic literature and in public debates.

(-) The descriptions of non-profit work/strategies that I encountered were quite general, vague and close-to-all-encompassing, such that it seemed difficult to discern clear ideas/stances on what kind of specific approaches should and should not be taken.

(-) I came across/was pointed to work by other researchers seeking to structure debates on tackling the risks from developments in artificial intelligence (Manheim and Englander 2021 (AI Alignment Forum), MMMaas 2022 (EA Forum), and Christiano 2020 (EAG talk)), and found their network-centered approach appealing.

- ^

The most prominent example of fictional explorations of weapons of mass destruction before the invention of the atomic bomb is probably H.G. Well’s The World Set Free, published in 1914 (Well 2007 [1914]).

- ^

There is ample literature on some dangers, such as the risk of an outbreak of nuclear war, but no discernible progress in figuring out how to reduce it effectively. For other issues, such as the role nuclear weapons may play in causing or precipitating existential catastrophe, direct academic engagement is more sparse, with few if any publications addressing relevant questions head-on (though substantial parts of the academic literature may contain useful insights for addressing those questions, even if the authors don’t recognize or highlight those).

- ^

Recently, there has been some discussion of difficulties encountered by effective altruists seeking to approach and adopt informed views on nuclear issues (see Jeff Lewis’ comments cited in Wiblin 2022 (EA Forum), and this other EA Forum post on “EA on nuclear war and expertise”: bean 2022).

- ^

“Longtermism is the view that positively influencing the long-term future is a key moral priority of our time” (definition given on the EA Forum).

- ^

The 80,000 Hours problem profile, for instance, states that work on nuclear risks is “sometimes recommended”, because “[t]his is a pressing problem to work on, but you may be able to have an even bigger impact by working on something else” (Hilton and McIntyre 2022).

- ^

I owe this classification of different nuclear risk assessments to my CERI mentor; all credit goes to them.

- ^

I think that it would be valuable and indeed necessary to conduct an assessment that compares all conceivable high-level outcomes. I did not do this for reasons of time limitation.

- ^

I have a slight concern regarding baked-in assumptions of the ITN framework (consequentialism, an ethics of numbers), which I struggle to pin down precisely. Because I feel unable to express which potential problem(s) I am worried about when using the ITN framework, I decided to tentatively accept the heuristic for the time being.

- ^

This seems true whether the decision is made for an individual and a group; “personal fit” is less useful as a heuristic for foundations/funders or for an outside-observer interested in the more abstract question of “How should this field be approached in general?”.

- ^

I recognize and endorse the criticism of state-centrism in the study of global politics. However, I believe that a focus on “state decisions” makes sense in this situation, seeing how states (or, rather, their high-level representatives) are the most likely candidates to engage in nuclear war.

- ^

It also seems potentially useful to ask and tackle a more specified version of this question, such as: What influences decision-making in current nuclear weapons states?, What influences decision-making in the contemporary United States?, Which actors have the best chance of influencing state decision-making?, …

- ^

Again, there are variations of the question that might be more approachable and equally valuable to get further insight on: What influences the relationship between the United States and China?, What encourages cooperative relations between states in our current (or a conceivable future) world?, …

- ^

To confirm this claim, and to get a sense of the variety of theoretical and empirical attempts to address these questions, I suggest consulting any International Relations or Global Politics textbook, e.g., e-ir’s free e-book International Relations Theory (McGlinchey, Walters and Scheinpflug 2017).

- ^

I am led to this hope because I think the epistemic practices and norms within the effective altruism community are exceptional and might allow its members to make significant advances to the way that analysis tends to be done in academia more broadly.I might well be overestimating the novelty and promise of “the EA mindset”, in which case working on these problems probably diminishes somewhat in expected value.

- ^

One criticism directed against the current status quo in nuclear politics is that the world is separated into states that own and states that do not own nuclear weapons, which constitutes an inherent injustice. It can be argued that an injustice of that kind is destabilizing for the world and detrimental to attempts to achieve global cooperation on shared goals and challenges, which is a complex causal claim that seems hard to evaluate for accuracy.

- ^

I am currently working on an essay-type write-up to clarify what I mean by this question specifically, why I think it’s important, and what my thoughts for an answer are. I plan to insert a short summary of that write-up and a link to it here once a first draft of it is completed. In the meantime, you can get a flavor of my thoughts in the concluding section of my write-up on promising strategies for reducing the probability of nuclear war.

- ^

These theories usually also emphasize the reverse relationship, i.e. the influence of real-world political and other structures on academic knowledge-production, but that part seems less relevant for my purposes here.