EcologyInterventions

Bio

Disenangling "nature."

It is my favorite thing, but I want to know its actual value.

Is it replaceable. Is it useful. Is it morally repugnant. Is it our responsibility. Is it valuable.

"I asked my questions. And then I discovered a whole world I never knew. That's my trouble with questions. I still don't know how to take them back."

Posts 3

Comments80

All but 3 bullet points were about AI. I know that AI is the number one catastrophic risk but I'm dyin' for variety (news on other fronts).

Here is the non-AI content:

- Allocation in the landscape seems more efficient than in the past – it’s harder to identify especially neglected interventions, causes, money, or skill-sets. That means it’s become more important to choose based on your motivations.

- Post-FTX, funding has become even more dramatically concentrated under Open Philanthropy, so finding new donors seems like a much bigger priority than in the past. (It seems plausible to me that $1bn in a foundation independent from OP could be worth several times that amount added to OP.)

- Both points mean efforts to start new foundations, fundraise and earn to give all seem more valuable compared to a couple of years ago.

(My bad if there were indications that this was going to be AI-centric from the outset, I could have easily missed some linguistic signals because I'm not the most savvy forum-goer.)

Thanks for posting this! This should really be a bigger discussion in conservation.

Heather Browning's reflection on their being some other reason we value biodiversity resonates.

McMahan's view is my own: that drawn out suffering from predation is wrong, but that ongoing predation is preferable to removing predation. Although I don't agree with their reasoning from uncertainty argument for keeping predation. Instead I have a jumbled mix of valuing autonomy, other lifestyles, thinking death by not-predation is worse, and valuing natural processes and complexity. This wavers against the benefits of a gardened wilderness because the potential for improvement is large and wide, but far off and requires high effort.

I need to think about these topics more. Great post.

I mostly agree with this - our powers and coordination are beyond impressive when we wield them. So a extinction risk would have to explain why we can't or don't use all of our resources to stop our own demise. Potential examples: feedback loops that are selfishly beneficial and prevent coordination, even if its leading to a slow death overall. Instances where the collapse is slow but locked-in ahead of time. So even if we decide to move heaven and earth to do something about it, its too late.

I remembered incorrectly - it was not the plastics, but the rare earths that they were recycling. Tanzeena Hussain was the graduate student working on it and having success getting bacteria to survive in increasingly toxic environments. She was crushing up old electronics to feed the bacteria - pretty on the nose.

It was in Elizabeth Skovran's lab at San Jose State University. This is the only write up I can find on it: https://blogs.sjsu.edu/newsroom/2023/taking-bio-recycling-to-the-next-level/

It looks like they are having enough success to file for a patent and investigate if this could eventually be a viable business too. But speeding this up at such early stages could be hugely beneficial to reducing mining and improving human health damaged by rare metal recovery.

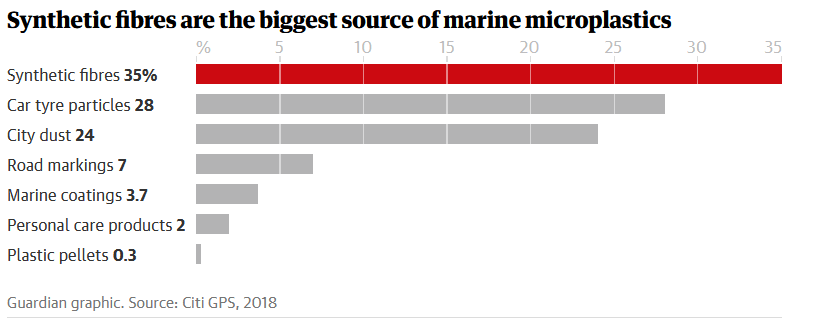

Recently I've been hearing tires are a major cause of air pollution and AND ocean plastic pollution.

I think some changes in tire requirements could go a LONG way to improving these as I doubt much effort has gone into improving tire material's environmental impact yet.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jul/25/tyre-dust-the-stealth-pollutant-becoming-a-huge-threat-to-ocean-life

https://www.thedrive.com/news/tire-dust-makes-up-the-majority-of-ocean-microplastics-study-finds

Looks like gov might be on the case, but perhaps we could get it moving wider and faster. "In the EU, the Euro 7 standards will regulate tire and brake emissions from 2025. In the U.S., the California EPA will require tire manufacturers to find an alternative chemical to 6PPD by 2024, to help reduce 6PPD-q entering the environment going forward. In turn, manufacturers are exploring everything from alternate tire compositions to special electrostatic methods to capture particulate output."

I've thought about this a little bit and then got stuck when it comes to figuring out where the big wins are and where the dead ends are.

In no particular order: Some metals are valuable. For this reason I don't think they are neglected but I also think the public doesn't know these metals should be recycled.

Recycling is almost certainly neglected because it is a public good that doesn't pay - these are pretty well always neglected.

Destroying things and making giant landfills feels bad and looks ugly but actually doesn't do as much damage as it feels like. The main reason that most waste campaigns give for more waste management is that it's destroying the earth. It's not. Getting an accurate picture of where the most damage occurs from bad waste management (perhaps polluted rivers in India? ghost nets left in the ocean?) is something very important and critical to the EA approach. As far as I know this hasn't been done yet. Not by EA and not by recycling orgs.

Recycling is tricky because there is the benefit of the materials (mostly estimated by their material value) but also the value of preventing more material from being gathered. (environmental damage) The material value is already pretty accurate I suspect. With one big caveat: As new forms of waste (for example plastic) appear, then it takes awhile for new forms of use (recycled plastic shoes? idk) to appear and value the material.

Some materials are so difficult to reuse that recycling them takes more energy and resources than simply disposing of them AND creating them anew. Those kinds of things ought to NOT be recycled! Maybe they should not created from the outset. Depends on how useful they are probably. Styrofoam is an example.

Environmental damage of creating more stuff is missing from the recycling economic math equation and is where potential important interventions would lie for society.

Toxic materials are a whole category that is very important and I know very little about. This is probably where the biggest improvements and most neglect is.

There are some cool new technologies to look into - a student I met was breeding bacteria to survive in highly metal contaminated environments to breakdown plastics and concentrate useful metals for waste management. Potentially a lot safer than human chemical processing.

Plastics are generally becoming more biodegradable. I'm not sure what body is pushing that to happen but it's a very good thing.

Furniture used to be a much bigger investment (like clothes were historically. People used to own 3-4 clothes and have them tailored. hard for us to imagine), but changing technology, culture, and mobility is turning furniture into a disposible resource. Potentially eventually almost as disposible as clothes. This seems like a big shift that recycling and reuse should anticipate and adapt to. Encouraging standards could go a long way to making furniture more valuable materials and increase the post-first-use value for both the purchaser, the recycler, and society.

First of all - great concept and great execution. Lots of interesting information and a lucid, well-supported conclusion.

My initial and I feel insufficiently addressed concern is that successful protests will of course be overlooked because in retrospect the technology they are protesting will seem "obviously doomed" or "not the right technology" etc. Additionally, successful protests are probably a lot shorter than the unsuccessful ones (which go on for years continuing to try to stop something that is never stopped). I'm not sure this is evidence that the successful protests "don't count" because they were "too small."

I see you considered some of this in your (very interesting) section on "other interesting examples of technological restraint" but I would emphasize these and others like them are quite relevant as long as they obey your other constraints of similar-enough motivation and technology.

I was not able to come up with any examples to contribute. I feel there are a significant subset of things (pesticides, internet structural decisions, nonstandard incompatible designs?) that were attractive but would have resulted in a worse future had they not been successfully diverted.

I can't stop checking the EA forum now....