Jackson Wagner

Bio

Scriptwriter for RationalAnimations! Interested in lots of EA topics, but especially ideas for new institutions like prediction markets, charter cities, georgism, etc. Also a big fan of EA / rationalist fiction!

Posts 19

Comments338

The Christians in this story who lived relatively normal lives ended up looking wiser than the ones who went all-in on the imminent-return-of-Christ idea. But of course, if christianity had been true and Christ had in fact returned, maybe the crazy-seeming, all-in Christians would have had huge amounts of impact.

Here is my attempt at thinking up other historical examples of transformative change that went the other way:

-

Muhammad's early followers must have been a bit uncertain whether this guy was really the Final Prophet. Do you quit your day job in Mecca so that you can flee to Medina with a bunch of your fellow cultists? In this case, it probably would've been a good idea: seven years later you'd be helping lead an army of 100,000 holy warriors to capture the city of Mecca. And over the next thirty years, you'll help convert/conquer all the civilizations of the middle east and North Africa.

-

Less dramatic versions of the above story could probably be told about joining many fast-growing charismatic social movements (like joining a political movement or revolution). Or, more relevantly to AI, about joining a fast-growing bay-area startup whose technology might change the world (like early Microsoft, Google, Facebook, etc).

-

You're a physics professor in 1940s America. One day, a team of G-men knock on your door and ask you to join a top-secret project to design an impossible superweapon capable of ending the Nazi regime and stopping the war. Do you quit your day job and move to New Mexico?...

-

You're a "cypherpunk" hanging out on online forums in the mid-2000s. Despite the demoralizing collapse of the dot-com boom and the failure of many of the most promising projects, some of your forum buddies are still excited about the possibilities of creating an "anonymous, distributed electronic cash system", such as the proposal called B-money. Do you quit your day job to work on weird libertarian math problems?...

People who bet everything on transformative change will always look silly in retrospect if the change never comes. But the thing about transformative change is that it does sometimes occur.

(Also, fortunately our world today is quite wealthy -- AI safety researchers are pretty smart folks and will probably be able to earn a living for themselves to pay for retirement, even if all their predictions come up empty.)

@ScienceMon🔸 There is vastly less of an "AI safety community" in China -- probably much less AI safety research in general, and much less of it, in percentage terms, is aimed at thinking ahead about superintelligent AI. (ie, more of China's "AI safety research" is probably focused on things like reducing LLM hallucinations, making sure it doesn't make politically incorrect statements, etc.)

- Where are the chinese equivalents of the American and British AISI government departments? Organizations like METR, Epoch, Forethought, MIRI, et cetera?

- Who are some notable Chinese intellectuals / academics / scientists (along the lines of Yoshua Bengio or Geoffrey Hinton) who have made any public statements about the danger of potential AI x-risks?

- Have any chinese labs published "responsible scaling plans" or tiers of "AI Safety Levels" as detailed as those from OpenAI, Deepmind, or Anthropic? Or discussed how they're planning to approach the challenge of aligning superintelligence?

- Have workers at any Chinese AI lab resigned in protest of poor AI safety policies (like the various people who've left OpenAI over the years), or resisted the militarization of AI technology (like googlers protesting Project Maven, or microsoft employees protesting the IVAS HMD program)?

When people ask this question about the relative value of "US" vs "Chinese" AI, they often go straight for big-picture political questions about whether the leadership of China or the US is more morally righteous, less likely to abuse human rights, et cetera. Personally, in these debates, I do tend to favor the USA, although certainly both the US and China have many deep and extremely troubling flaws -- both seem very far from the kind of responsible, competent, benevolent entity to whom I would like to entrust humanity's future.

But before we even get to that question of "What would national leaders do with an aligned superintelligence, if they had one," we must answer the question "Do this nation's AI labs seem likely to produce an aligned superintelligence?" Again, the USA leaves a lot to be desired here. But oftentimes China seems to not even be thinking about the problem. This is a huge issue from both a technical perspective (if you don't have any kind of plan for how you're going to align superintelligence, perhaps you are less likely to align superintelligence), AND from a governance perspective (if policymakers just think of AI as a tool for boosting economic / military progress and haven't thought about the many unique implications of superintelligence, then they will probably make worse decisions during an extremely important period in history).

Now, indeed -- has Trump thought about superintelligence? Obviously not -- just trying to understand intelligent humans must be difficult for him. But the USA in general seems much more full of people who "take AI seriously" in one way or another -- sillicon-valley CEOs, pentagon advisers, billionare philanthropists, et cetera. Even in today's embarassing administration, there are very high-ranking people (like Elon Musk and J. D. Vance) who seem at least aware of the transformative potential of AI. China's government is more opaque, so maybe they're thinking about this stuff too. But all public evidence suggests to me that they're kinda just blindly racing forward, trying to match and surpass the West on capabilities, without giving much thought as to where this technology might ultimately go.

Pretty much all company owners (or the respective investors) believe that they are most knowledgeable about what's the best way to reinvest income.

Unfortunately, mostly they overestimate their own knowledge in this regard.

The idea that random customers would be better at corporate budgeting than the people who work in those companies and think about corporate strategy every day, is a really strong claim, and you should try to offer evidence for this claim if you want people to take your fintech idea seriously.

Suppose I buy a new car from Toyota, and now I get to decide how Toyota invests the $10K of profit they made by selling me the car. There are immediately so many problems:

- How on earth am I supposed to make this decision?? Should they spend the money on ramping up production of this exact car model? Or should they spend the money on R&D to make better car engines in the future? Or should they save up money to buy an electric-vehicle battery manufacturing startup? Maybe they should just spend more on advertising? I don't know anything about running a car company. I don't even know what their current budget is -- maybe advertising was the best use of new funds last year, but this year they're already spending a ton on advertising, and it would be better to simply return additional profits to shareholders rather than over-expand?

- Would it be Toyota's job to give me tons of material that I could read, to become informed and make the decision properly? But then wouldn't Toyota just end up making all the decisions anyway, in the form of "recommendations", that customers would usually agree with?

- Wouldn't a lot of this information be secret / internal data, such that giving it away would unduly help rival companies?

- Maybe an idea is popular and sounds good, but is actually a terrible idea for some subtle reason. For example, "Toyota should pivot to making self-driving cars powered by AI" sounds like a good idea to me, but I'm guessing that the reason Toyota isn't doing it is that it would be pretty difficult for them to become a leader in self-driving technology. If ill-informed customers were making decisions, wouldn't we expect follies like this to happen all the time?

- Would it be Toyota's job to give me tons of material that I could read, to become informed and make the decision properly? But then wouldn't Toyota just end up making all the decisions anyway, in the form of "recommendations", that customers would usually agree with?

- How is everyone supposed to find the time to be constantly researching different corporations? Last month I bought a car and had to become a Toyota expert, this month I bought a new TV from Samsung, next month I'll upgrade my Apple iphone, or maybe buy a Nintendo switch. And let's not forget all the grocery shopping I do, restaurant meals, etc innumerable small purchases.

- What happens to all the votes of the people who never bother to engage with this system? What's the incentive for customers to spend time making corporate decisions?

- It seems like you'd need some kind of liquid-democracy-style delegation system for this to work properly, and not take up everyone's time. Like, maybe you'd delegate most coporate decision-making power to a single expert who we think knows the most about the company (we could call this person a "CEO"), and then have a wider circle of people that oversee the CEO's behavior and fire them if necessary (this could be a "board of directors"), and then a wider circle of people who are generally interested in that company (these might be called "shareholders") could determine who's on the board of directors...

Hello!

I'm glad you found my comment useful! I'm sorry if it came across as scolding; I interpreted Tristan's original post to be aimed at advising giant mega-donors like Open Philanthropy, moreso than individual donors. In my book, anybody donating to effective global health charities is doing a very admirable thing -- especially in these dark days when the US government seems to be trying to dismantle much of its foreign aid infrastructure.

As for my own two cents on how to navigate this situation (especially now that artificial intelligence feels much more real and pressing to me than it did a few years ago), here are a bunch of scattered thoughts (FYI these bullets have kind of a vibe of "sorry, i didn't have enough time to write you a short letter, so I wrote you a long one"):

- My scold-y comment on Tristan's post might suggest a pretty sharp dichotomy, where your choice is to either donate to proven global health interventions, or else to fully convert to longtermism and donate everything to some weird AI safety org doing hard-to-evaluate-from-the-outside technical work.

- That's a frustrating choice for a lot of reasons -- it implies totally pivoting your giving to a new field, where it might no longer feel like you have a special advantage in picking the best opportunities within the space. It also means going all-in on a very specific and uncertain theory of impact (cue the whole neartermist-vs-longtermist debate about the importance of RCTs, feedback loops, and tangible impact, versus ideas like "moral uncertainty" that m.

- You could try to split your giving 50/50, which seems a little better (in a kind of hedging-your-bets way), but still pretty frustrating for various reasons...

- I might rather seek to construct a kind of "spectrum" of giving opportunities, where Givewell-style global health interventions and longtermist AI existential-risk mitigation define the two ends of the spectrum. This might be a dumb idea -- what kinds of things could possibly be in the middle of such a bizarre spectrum? And even if we did find some things to put in the middle, what are the chances that any of them would pass muster as a highly-effective, EA-style opportunity? But I think possibly there could actually be some worthwhile ideas here. I will come back to this thought in a moment.

- Meanwhile, I agree with Tristan's comment here that it seems like eventually money will probably cease to be useful -- maybe we go extinct, maybe we build some kind of coherent-extrapolated-volition utopia, maybe some other similarly-weird scenario happens.

- (In a big-picture philosophical sense, this seems true even without AGI? Since humanity would likely eventually get around to building a utopia and/or going extinct via other means. But AGI means that the transition might happen within our own lifetimes.)

However, unless we very soon get a nightmare-scenario "fast takeoff" where AI recursively self-improves and seizes control of the future over the course of hours-to-weeks, it seems like there will probably be a transition period, where approximately human-level AI is rapidly transforming the economy and society, but where ordinary people like us can still substantially influence the future. There are a couple ways we could hope to influence the long-term future:

- We could simply try to avoid going extinct at the hands of misaligned ASI (most technical AI safety work is focused on this)

- If you are a MIRI-style doomer who believes that there is a 99%+ chance that AI development leads to egregious misalignment and therefore human extinction, then indeed it kinda seems like your charitable options are "donate to technical alignment research", "donate to attempts to implement a global moratorium on AI development", and "accept death and donate to near-term global welfare charities (which now look pretty good, since the purported benefits of longtermism are an illusion if there is effectively a 100% chance that civilization ends in just a few years/decades)". But if you are more optimistic than MIRI, then IMO there are some other promising cause areas that open up...

- There are other AI catastrophic risks aside from misalignment -- gradual disempowerment is a good example, as are various categories of "misuse" (including things like "countries get into a nuclear war as they fight over who gets to deploy ASI")

- Interventions focused on minimizing the risk of these kinds of catastrophes will look different -- finding ways to ease international tensions and cooperate around AI to avoid war? Advocating for georgism and UBI and designing new democratic mechanisms to avoid gradual disempowerment? Some of these things might also have tangible present-day benefits even aside from AI (like reducing the risks of ordinary wars, or reducing inequality, or making democracy work better), which might help them exist midway on the spectrum I mentioned earlier, from tangible givewell-style interventions to speculative and hard-to-evaluate direct AI safety work.

- Even among scenarios that don't involve catastrophes or human extinction, I feel like there is a HUGE variance betwen the best possible worlds, and the median outcome. So there is still tons of value in pushing for a marginally better future -- CalebMaresca's answer mentions the idea that it's not clear whether animals would be invited along for the ride in any future utopia. This indeed seems like an important thing to fight for. I think there are lots of things like this -- there are just so many different possible futures.

- (For example, if we get aligned ASI, this doesn't answer the question of whether ordinary people will have any kind of say in crafting the future direction of civilization; maybe people like Sam Altman would ideally like to have all the power for themselves, benevolently orchestrating a nice transhumanist future wherein ordinary people get to enjoy plenty of technological advancements, but have no real influence over the direction of which kind of utopia we create. This seems worse to me than having a wider process of debate & deliberation about what kind of far future we want.)

- CalebMaresca's answer seems to imply that we should be saving all our money now, to spend during a post-AGI era that they assume will look kind of neo-feudal. This strikes me as unwise, since a neo-feudal AGI semi-utopia is a pretty specific and maybe not especially likely vision of the future! Per Tristan's comment that money will eventually cease to be useful, it seems like it probably makes the most sense to deploy cash earlier, when the future is still very malleable:

- In the post-ASI far future, we might be dead and/or money might no longer have much meaning and/or the future might already be effectively locked in / out of our control.

- In the AGI transition period, the future will still be very malleable, we will probably have more money than we do now (although so will everyone else), and it'll be clearer what the most important / neglected / tractable things are to focus on. The downside is that by this point, everyone else will have realized that AGI is a big deal, lots of crazy stuff will be happening, and it might be harder to have an impact because things are less neglected.

- Today, lots of AI-related stuff is neglected, but it's also harder to tell what's important / tractable.

For a couple of examples of interventions that could exist midway along a spectrum from givewell-style interventions to AI safety research, which are also focused on influencing the transitional period of AGI, consider Dario Amodei's vision of what an aspirational AGI transition period might look like, and what it would take to bring it about:

- Dario talks about how AI-enhanced biological research could lead to amazing medical breakthroughs. To allow this to happen more quickly, it might make sense to lobby to reform the FDA or the clinical trial system. It also seems like a good idea to lobby for the most impactful breakthroughs to be quickly rolled out, even to people in poor countries who might not be able to afford them on their own. Getting AI-driven medical advances to more people, more quickly would of course benefit the people for whom the treatments arrive just in time. But it might also have important path-dependent effects on the long-run future, by setting precedents and infuencing culture and etc.

- In the section on "neuroscience and mind", Dario talks about the potential for an "AI coach who always helps you to be the best version of yourself, who studies your interactions and helps you learn to be more effective". Maybe there is some way to support / accelerate the development of such tools?

- Dario is thinking of psychology and mental health here. (Imagine a kind of supercharged, AI-powered version of Happier-Lives-Institute-style wellbeing interventions like StrongMinds?) But there could be similarly wide potential for disseminating AI technology for promoting economic growth in the third world (even today's LLMs can probably offer useful medical advice, engineering skills, entrepeneurial business tips, agricultural productivity best practices, etc).

- Maybe there's no angle for philanthropy in promoting the adoption of "AI coach" tools, since people are properly incentivized to use such tools and the market will presumably race to provide them (just as charitable initiatives like OneLaptopPerChild ended up much less impactful than ordinary capitalism manufacturing bajillions of incredibly cheap smartphones). But who knows; maybe there's a clever angle somewhere.

- He mentions a similar idea that "AI finance ministers and central bankers" could offer good economic advice, helping entire countries develop more quickly. It's not exactly clear to me why he expects nations to listen to AI finance ministers more than ordinary finance ministers. (Maybe the AIs will be more credibly neutral, or eventually have a better track record of success?) But the general theme of trying to find ways to improve policy and thereby boost economic growth in LMIC (as described by OpenPhil here) is obviously an important goal for both the tangible benefits, and potentially for its path-dependent effects on the long-run future. So, trying to find some way of making poor countries more open to taking pro-growth economic advice, or encouraging governments to adopt efficiency-boosting AI tools, or convincing them to be more willing to roll out new AI advancements, seem like they could be promising directions.

- Finally he talks about the importance of maintaining some form of egalitarian / democratic control over humanity's future, and the idea of potentially figuring out ways to improve democracy and make it work better than it does today. I mentioned these things earlier; both seem like promising cause areas.

"However, the likely mass extinction of K-strategists and the concomitant increase in r-selection might last for millions of years."

I like learning about ecology and evolution, so personally I enjoy these kinds of thought experiments. But in the real world, isn't it pretty unlikely that natural ecosystems will just keep humming along for another million years? I would guess that within just the next few hundred years, human civilization will have grown in power to the point where it can do what it likes with natural ecosystems:

- perhaps we bulldoze the earth's surface in order to cover it with solar panels, fusion power plants, and computronium?

- perhaps we rip apart the entire earth for raw material to be used for the construction of a Dyson swarm?

- more prosaically, maybe human civilization doesn't expand to the stars, but still expands enough (and in a chaotic, unsustainable way) such that most natural habitats are destroyed

- perhaps there will have been a nuclear war (or some other similarly devastating event, like the creation of mirror life that devastates the biosphere)

- perhaps we create unaligned superintelligent AI which turns the universe into paperclips

- perhaps humanity grows in power but also becomes more responsible and sustainable, and we reverse global warming using abundant clean energy powering technologies like carbon air capture, assorted geoengineering techniques, etc

- perhaps humanity attains a semi-utopian civilization, and we decide to extensively intervene in the natural world for the benefit of nonhuman animals

- etc

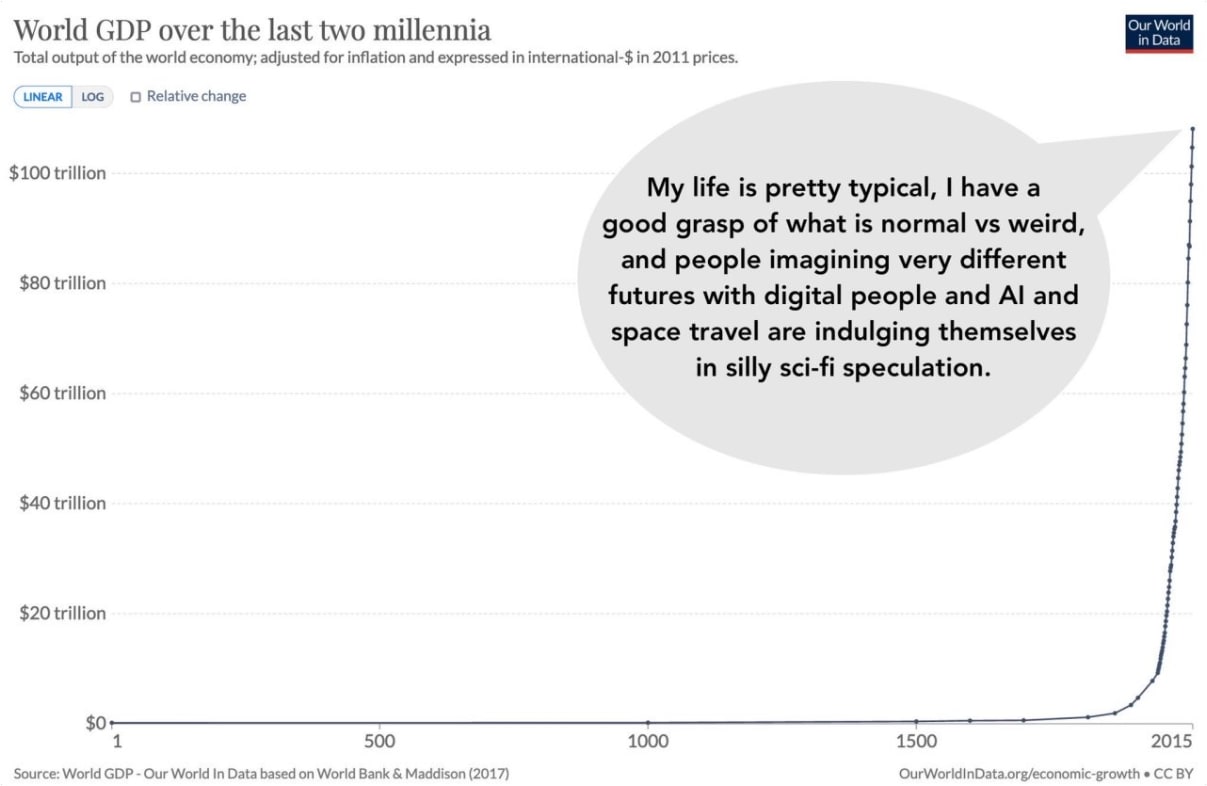

Some of those scenarios might be dismissable as the kind of "silly sci-fi speculation" mentioned by the longtermist-style meme below. But others seem pretty mundane, indeed "to be expected" even by the most conservative visions of the future. To me, the million-year impact of things like climate change only seems relevant in scenarios where human civilization collapses pretty soon, but in a way that leaves Earth's biosphere largely intact (maybe if humans all died to a pandemic?).

Infohazards are indeed a pretty big worry of lots of the EAs working on biosecurity: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/PTtZWBAKgrrnZj73n/biosecurity-culture-computer-security-culture

IMO, one helpful side effect (albeit certainly not a main consideration) of making this work public, is that it seems very useful to have at least one worst-case biorisk that can be publicly discussed in a reasonable amount of detail. Previously, the whole field / cause area of biosecurity could feel cloaked in secrecy, backed up only by experts with arcane biological knowledge. This situation, although unfortunate, is probably justified by the nature of the risks! But still, it makes it hard for anyone on the outside to tell how serious the risks are, or understand the problems in detail, or feel sufficiently motivated about the urgency of creating solutions.

By disclosing the risks of mirror bacteria, there is finally a concrete example to discuss, which could be helpful even for people who are actually even more worried about, say, infohazardous-bioengineering-technique-#5, than they are about mirror life. Just being able to use mirror life as an example seems like it's much healthier than having zero concrete examples and everything shrouded in secrecy.

Some of the cross-cutting things I am thinking about:

- scientific norms about whether to fund / publish risky research

- attempts to coordinate (on a national or international level) moratoriums against certain kinds of research

- the desirability of things like metagenomic sequencing, DNA synthesis screening for harmful sequences, etc

- research into broad-spectrum countermeasures like UVC light, super-PPE, pipelines for very quick vaccine development, etc

- just emphasising the basic overall point that global catastrophic biorisk seems quite real and we should take it very seriously

- and probably lots of other stuff!

So, I think it might be a kind of epistemic boon for all of biosecurity to have this public example, which will help clarify debates / advocacy / etc about the need for various proposed policies or investments.

Thinking about my point #3 some more (how do you launch a satellite after a nuclear war). I realized that if you put me in charge of making a plan to DIYing this (instead of lobbying the US military to do it for me, which would be my first choice), and if SpaceX also wasn't answering my calls to see if I could buy any surplus starlinks...

You could do worse than partnering with Rocketlab, a satellite and rocket company based in New Zealand, developing the emergency satellite based on their "Photon" platform (design has flown before, small enough to still be kinda cheap, big enough to generate much more power than a cubesat). Then Rocketlab can launch their Electron rocket from New Zealand in the event of a nuclear war, and (in a real crisis like that), the whole company would help make sure the mission happened -- the idea of partnering with someone rather than just buying a satellite is key, IMO, because then it's mostly THEIR end of the world plan and in a crisis would benefit from their expertise / workforce.

I'd try to talk to the CEO, get him on board. Seems like the kind of flashy, Elon-esque, altruistic-in-a-sexy-way mission that could help with making RocketLab seem "cool" and recruiting eager mission-driven employees. (RocketLab's CEO currently has ambitions to do some similar flashy missions, like sending their own probe to Venus.)

But this would definitely be more like a $30M project, than a $300K project.

To answer with a sequence of increasingly "systemic" ideas (naturally the following will be tinged by by own political beliefs about what's tractable or desirable):

There are lots of object-level lobbying groups that have strong EA endorsement. This includes organizations advocating for better pandemic preparedness (Guarding Against Pandemics), better climate policy (like CATF and others recommended by Giving Green), or beneficial policies in third-world countries like salt iodization or lead paint elimination.

Some EAs are also sympathetic to the "progress studies" movement and to the modern neoliberal movement connected to the Progressive Policy Institute and the Niskasen Center (which are both tax-deductible nonprofit think-tanks). This often includes enthusiasm for denser ("yimby") housing construction, reforming how science funding and academia work in order to speed up scientific progress (such as advocated by New Science), increasing high-skill immigration, and having good monetary policy. All of those cause areas appear on Open Philanthropy's list of "U.S. Policy Focus Areas".

Naturally, there are many ways to advocate for the above causes -- some are more object-level (like fighting to get an individual city to improve its zoning policy), while others are more systemic (like exploring the feasibility of "Georgism", a totally different way of valuing and taxing land which might do a lot to promote efficient land use and encourage fairer, faster economic development).

One big point of hesitancy is that, while some EAs have a general affinity for these cause areas, in many areas I've never heard any particular standout charities being recommended as super-effective in the EA sense... for example, some EAs might feel that we should do monetary policy via "nominal GDP targeting" rather than inflation-rate targeting, but I've never heard anyone recommend that I donate to some specific NGDP-targeting advocacy organization.

I wish there were more places like Center for Election Science, living purely on the meta level and trying to experiment with different ways of organizing people and designing democratic institutions to produce better outcomes. Personally, I'm excited about Charter Cities Institute and the potential for new cities to experiment with new policies and institutions, ideally putting competitive pressure on existing countries to better serve their citizens. As far as I know, there aren't any big organizations devoted to advocating for adopting prediction markets in more places, or adopting quadratic public goods funding, but I think those are some of the most promising areas for really big systemic change.