Seth Ariel Green

Bio

Participation1

I am a Research Scientist at the Humane and Sustainable Food Lab at Stanford and a nonresident fellow at the Kahneman-Treisman Center at Princeton. By trade, I am a meta-analyst.

Posts 9

Comments127

Topic contributions1

Definitely! When I went vegan, I prompted someone I know to look up how dairy cows are treated (not well), and they changed their diet quite a bit in light of that. So I have seen downstream effects personally. Caveat that I am annoying and prone to evangelize.

And if i were going to promote one definitely-not-scalable intervention to one very-hard-to-reach-population, I would take a bunch of die-hard meat eaters to Han Dynasty on the upper west side of Manhattan and order 1) DanDan noodles without pork 2) pea leaves with garlic 3) cumin tofu 4) kung pao tofu and 5) eggplant in garlic sauce for the table, and then just be "like hello is this not delicious??" every 30 seconds 😃

That sounds very interesting!

Making things more pleasant for vegetarians and vegans is a good thing to do, even if it does not change other people's behavior too much.

In the long-run, we want to make vegetarianism seem just as "nice, natural, and normal" (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666315001518) as eating meat.

I think things like a Meatless Monday Lunch are very helpful for that.

Hi there,

-

Delays run the gamut. Jalil et al (2023) measure three years worth of dining choices, Weingarten et al. a few weeks; other studies are measuring what’s eaten at a dining hall during treatment and control but with no individual outcomes; and other studies are structured recall tasks like 3/7/30 days after treatment that ask people to say what they ate in a 24 hour period or over a given week. We did a bit of exploratory work on the relationship between length of delay and outcome size and didn’t find anything interesting.

-

I’m afraid we don’t know that overall. A few studies did moderator analysis where they found that people who scored high on some scale or personality factor tended to reduce their MAP consumption more, but no moderator stood out to us as a solid predictor here. Some studies found that women seem more amenable to messaging interventions, based on the results of Piester et al. 2020 and a few others, but some studies that exclusively targeted women found very little. I think gendered differences are interesting here but we didn't find anything conclusive.

Hi Wayne,

Great questions, I'll try to give them the thoughtful treatment they deserve.

- We don't place much (any?) credence in the statistical significance of the overall result, and I recognize that a lot of work is being done by the word "meaningfully" in "meaningfully reducing." For us, changes on the order of a few percentage points -- especially given relatively small samples & vast heterogeneity of designs and contexts (hence our point about "well-validated" -- almost nothing is directly replicated out of sample in our database) -- are not the kinds of transformational change that others in this literature have touted. Another way to slice this, if you were looking to evaluate results based on significance, is to look at how many results are, according to their own papers, statistical nulls: 95 out of 112, or about 85%. (On the other hand, many of these studies might be finding small but real effects but not be sufficiently powered to identify them: If you plan for d > 0.4, an effect of d = 0.04 is going to look like a null, even if real changes are happening). So my basic conclusion is that marginal changes probably are possible, so in that sense, yes, many of these interventions probably "work," but I wouldn't call the changes transformative. I think the proliferation of GLP-1 drugs is much more likely to be transformative.

- It's true that cost-effectiveness estimates might still be very good even if the results are small. If there was a way to scale up the Jalil et al. intervention, I'd probably recommend it right away. But I don't know of any such opportunity. (It requires getting professors to substitute out a normal economics lecture for one focused on meat consumption, and we'd probably want at least a few other schools to do measurement to validate the effect, and my impression from talking to the authors is that measurement was a huge lift). I also think that choice architecture approaches are promising and awaiting a new era of evaluation. My lab is working on some of these; for someone interested in supporting the evaluation side of things, donating to the lab might be a good fit.

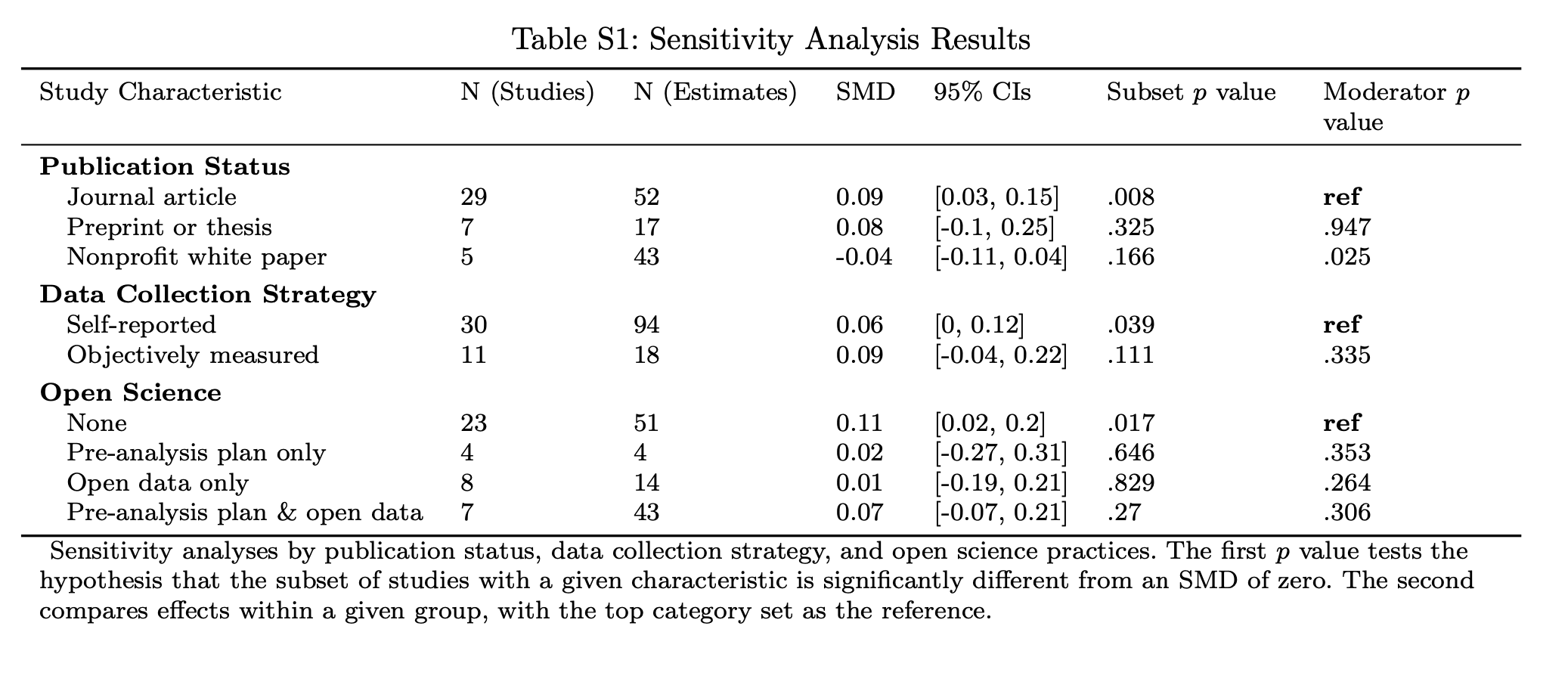

This is in the supplement rather than the paper, but one of our depressing results is that rigorous evaluations published by nonprofits, such as The Humane League, Mercy For Animals, and Faunalytics, produce a small backlash on average (see table below). But it's also my impression that a lot of these groups have changed gears a lot, and are now focusing less on (e.g.) leafletting and direct persuasion efforts and more on corporate campaigns, undercover investigations, and policy work. I don't know if they have moved this direction specifically because a lot of their prior work was showing null/backlash results, but in general I think this shift is a good idea given the current research landscape.

4. Pursuant to that, economists working on this sometimes talk about the consumer-citizen gap, where people will support policies that ban practices whose products they'll happily consume. (People are weird!) For my money, if I were a significant EA donor on this space, I might focus here: message testing ballot initiatives, preparing for lengthy legal battles, etc. But as always with these things, the details matter. If you ban factory farms in California and lead Californians to source more of their meat from (e.g.) Brazil, and therefore cause more of the rainforest to be clearcut -- well that's not obviously good either.

5. Almost all interventions in our database targeted meat rather than other animal products (one looked at fish sauce and a couple also measured consumption of eggs and dairy). Also a lot of studies just say the choice was between a meat dish and a vegetarian dish, and whether that vegetarian dish contained eggs or milk is sometimes omitted. But in general, I'd think of these as "less meat" interventions.

Sorry I can't offer anything more definitive here about what works and where people should donate. An economist I like says his dad's first rule of social science research was: "Sometimes it’s this way, and sometimes it’s that way," and I suppose I hew to that 😃

👋 Great questions!

- Most studies in our dataset don't report these kinds of fine-grained results, but in general my impression from the texts is that the typical study gets a lot of people to change their behavior a little. (In part because if they got people to go vegan I expect they would say that.)

- Some studies deliberately exclude vegetarians as part of their recruitment process, but most just draw from whatever population at large. Somewhere between 2 and 5% of people identify as vegetarians (and many of them eat meat sometimes), so I don't personally worry too much about this curtailing results. A few studies specifically recruit people who are motivated to change their diets and/or help animals, e.g. Cooney (2016) recruited people who wanted to help Mercy for Animals evaluate its materials.

- I think this is a fair mental model, but I think one of the main open questions of our paper is about how do we recruit people to cut back on meat in general vs. just cutting back on a few categories, e.g. red and processed meat. So I guess my mental model is that most people have heard that raising cows is bad for the environment and those who are cutting back are substituting partly to plant-based substitutes (reps from Impossible Foods noted at a recent meeting that most of their customers also eat meat) and partly to chicken and fish, e.g. the Mayo Clinic's page on heart-healthy diets suggests "Lean meat, poultry and fish; low-fat or fat-free dairy products; and eggs are some of the best sources of protein...Fish is healthier than high-fat meats", although it also says that "Eating plant protein instead of animal protein lowers the amounts of fat and cholesterol you take in."

So I'd say we still have a lot of open questions...

👋 Our pleasure!

To the best of my recollection, the only paper in our dataset that provides a cost-benefit estimation is Jalil et al. (2023)

Calculations indicate a high return on investment even under conservative assumptions (~US$14 per metric ton CO2eq). Our findings show that informational interventions can be cost effective and generate long-lasting shifts towards more sustainable food options.

There's also a red/processed meat study --- Emmons et al. (2005) --- that does some cost-effectiveness analyses, but it's almost 20 years old and its reporting is really sparse: changes to the eating environment "were not reported in detail, precluding more detailed analyses of this intervention." So I'd stick with Jalil et al. to get a sense of ballpark estimates.

Agreed that it's hard to implement: much easier to say "vegetarian food is popular at this cafe!' than to convince people that they are expected to eat vegetarian.

See here for a review of the 'dynamic norms' part of this literature (studies that tell people that vegetarianism is growing in popularity over time): https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/qfn6y

Thank you David! We will post any updates to https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/q6xyr

The paper is currently under submission at a journal and we likely won’t modify it until we get some feedback.