Katja Grace, 8 March 2023

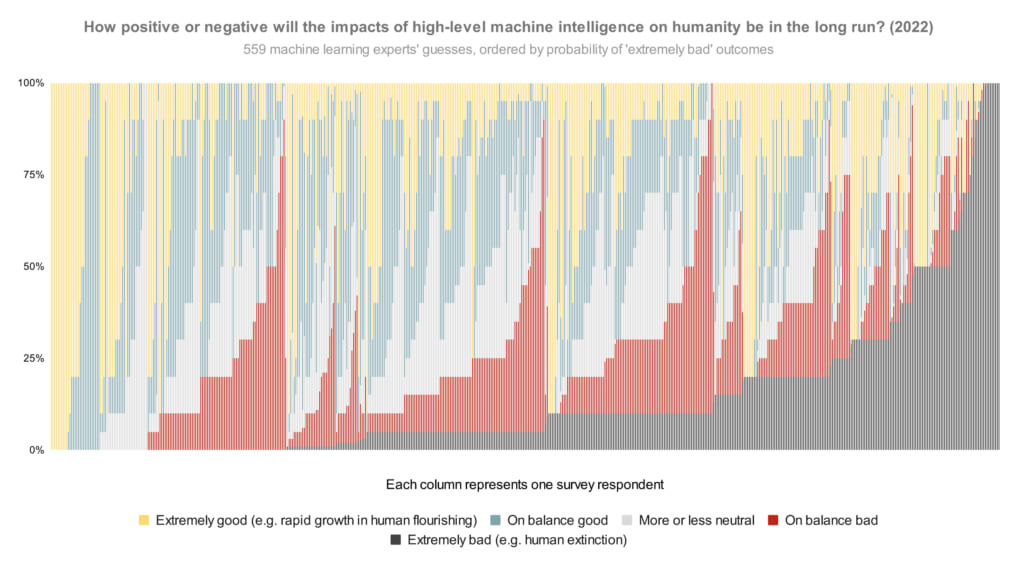

In our survey last year, we asked publishing machine learning researchers how they would divide probability over the future impacts of high-level machine intelligence between five buckets ranging from ‘extremely good (e.g. rapid growth in human flourishing)’ to ‘extremely bad (e.g. human extinction).1 The median respondent put 5% on the worst bucket. But what does the whole distribution look like? Here is every person’s answer, lined up in order of probability on that worst bucket:

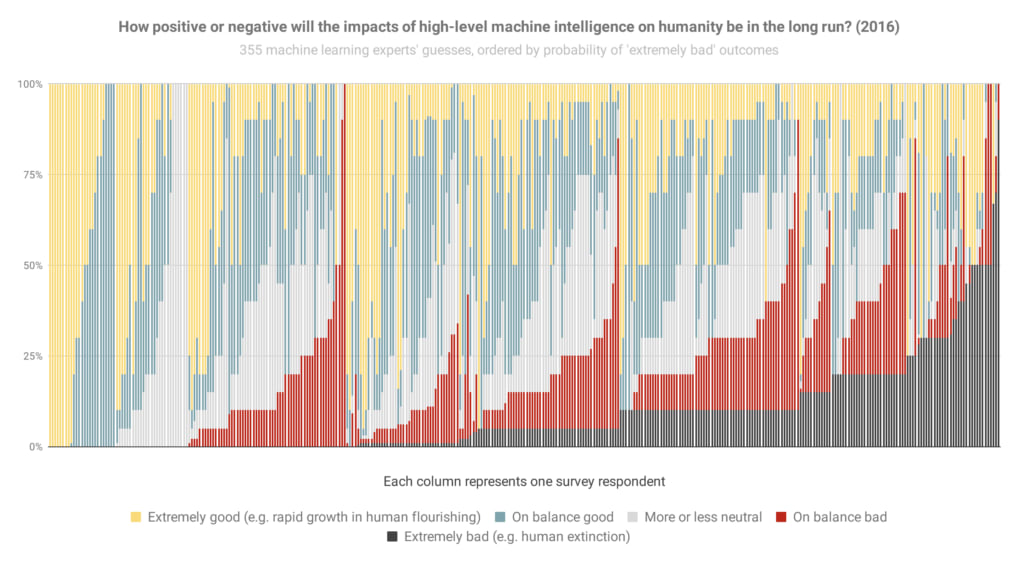

And here’s basically that again from the 2016 survey (though it looks like sorted slightly differently when optimism was equal), so you can see how things have changed:

The most notable change to me is the new big black bar of doom at the end: people who think extremely bad outcomes are at least 50% have gone from 3% of the population to 9% in six years.

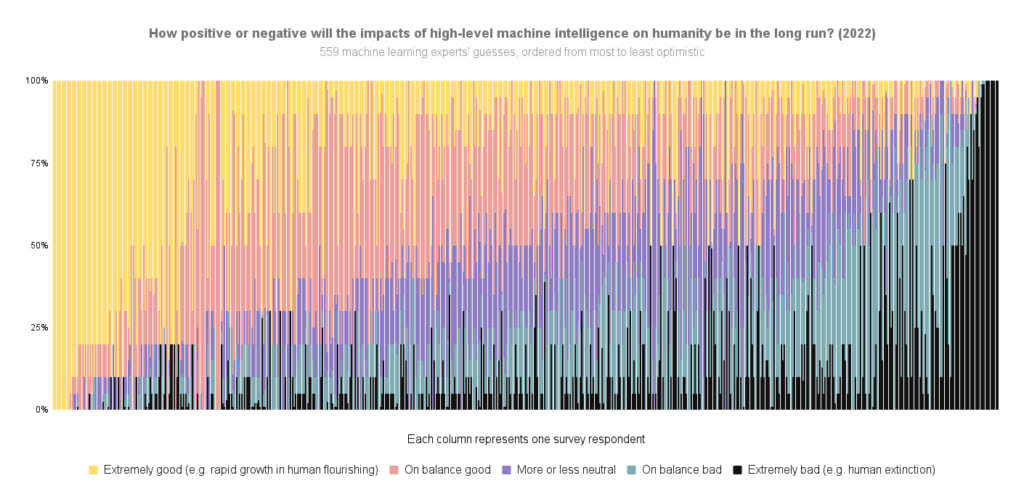

Here are the overall areas dedicated to different scenarios in the 2022 graph (equivalent to averages):

- Extremely good: 24%

- On balance good: 26%

- More or less neutral: 18%

- On balance bad: 17%

- Extremely bad: 14%

That is, between them, these researchers put 31% of their credence on AI making the world markedly worse.

Some things to keep in mind in looking at these:

- If you hear ‘median 5%’ thrown around, that refers to how the researcher right in the middle of the opinion spectrum thinks there’s a 5% chance of extremely bad outcomes. (It does not mean, ‘about 5% of people expect extremely bad outcomes’, which would be much less alarming.) Nearly half of people are at ten percent or more.

- The question illustrated above doesn’t ask about human extinction specifically, so you might wonder if ‘extremely bad’ includes a lot of scenarios less bad than human extinction. To check, we added two more questions in 2022 explicitly about ‘human extinction or similarly permanent and severe disempowerment of the human species’. For these, the median researcher also gave 5% and 10% answers. So my guess is that a lot of the extremely bad bucket in this question is pointing at human extinction levels of disaster.

- You might wonder whether the respondents were selected for being worried about AI risk. We tried to mitigate that possibility by usually offering money for completing the survey ($50 for those in the final round, after some experimentation), and describing the topic in very broad terms in the invitation (e.g. not mentioning AI risk). Last survey we checked in more detail—see ‘Was our sample representative?’ in the paper on the 2016 survey.

Here’s the 2022 data again, but ordered by overall optimism-to-pessimism rather than probability of extremely bad outcomes specifically:

For more survey takeaways, see this blog post. For all the data we have put up on it so far, see this page.

See here for more details.

Thanks to Harlan Stewart for helping make these 2022 figures, Zach Stein-Perlman for generally getting this data in order, and Nathan Young for pointing out that figures like this would be good.

Katja - thanks for posting these survey data.

They results are shocking. Really shocking. Appalling, really. It's worth taking a few minutes to soak in the dark implications.

It's hard to imagine any other industry full of smart people in which researchers themselves realize that what they're doing is barely likely to have a net positive impact on the world. And in which a large proportion believe that they're likely to impose massive suffering and catastrophe on everyone -- including their own friends, families, and kids.

Yet that's where we are with the AI industry. Almost all of the ML researchers seem to understand 'We might be the baddies'. And a much higher proportion seem to understand the catastrophic risks in 2022 than in 2016.

Yet they carry on doing what they're doing, despite knowing the risks. Perhaps they're motivated by curiosity, hubris, wealth, fame, status, or prestige. (Aren't we all?) Perhaps these motives overwhelm their moral qualms about what they're doing.

But IMHO, any person with ethical integrity who found themselves working in an industry where the consensual prediction among their peers is that their work is fairly likely to lead straight to an extinction-level catastrophe would take a step back, re-assess, and re-think whether they should really be pushing ahead.

I know all the arguments about the inevitability of AI arms races, between companies and between nation-states. But we're not really in a geopolitical arms race. There are very few countries with the talent, money, GPU clusters, and determination to pursue advanced AI. North Korea, Iran, Russia, and other dubious nations are not going to catch up any time soon. China is falling behind, relatively speaking.

The few major players in the American AI industry are far, far more advanced than the companies in any other country at this point. We're really just talking about a few thousand ML researchers associated with OpenAI/Microsoft, Deepmind/Google, and a handful of other companies. Almost all American. Pushing ahead, knowing the risks, knowing they're far in advance of any other country. It's insane. It's sociopathic. And I don't understand why EAs are still bending over backwards to try to stay friendly with this industry, trying to gently nudge them into taking 'alignment' more seriously, trying to portray them as working for the greater good. They are the baddies, and they increasingly know it, and we know it, and we should call them out on it.

Sorry for the feisty tone here. But sometimes moral outrage is the appropriate response to morally outrageous behavior by a dangerous industry.

"Yet they carry on doing what they're doing, despite knowing the risks. Perhaps they're motivated by curiosity, hubris, wealth, fame, status, or prestige. (Aren't we all?) Perhaps these motives overwhelm their moral qualms about what they're doing."

I'd like to add inertia/comfort to this list: people don't like to change jobs, and changing fields is much harder.

Intervention idea: offer capabilities researchers support to transition out of the field

I think this would be counterproductive. Most ML researchers don't think the research they personally work on is dangerous, or could be dangerous, or contributes to a research direction that could be dangerous, and most of them actually are right about this. There is all kinds of stuff people work on that's not on the critical path to dangerous AI.

Granted, moral outrage can sometimes be counterproductive.

However, we have no idea which specific ML work is 'on the critical path to dangerous AI'. Maybe most of it isn't. But maybe most of it is, one way or another.

ML researchers are clever enough to tell themselves reassuring stories about how whatever they're working on is unlikely to lead straight to dangerous AI. Just as most scientists working on nuclear weapon systems during the Cold War could tell themselves stories like 'Sure, I'm working on ICBM rockets, but at least I'm not working on ICBM guidance systesm', or 'Sure, I'm working on guidance systems, but at least I'm not working on the nuclear payloads', or 'Sure, I'm working on simulating the nuclear payload yields, but at least I'm not physically loading the enriched uranium into the warheads'. The smarter people are, the better they tend to be at motivated reasoning, and at creating plausible deniability that they played any role in increasing existential risk.

However, there's no reason for the rest of us to trust individual ML researchers' assessments of which work is dangerous, versus which is safe. Clearly a large proportion of ML researchers think that what other ML researchers are doing is potentially dangerous. And maybe we should listen to them about that.

I think a better analogy than "ICBM engineering" might be "all of aeronautical engineering and also some physicists studying fluid dynamics". If you were an anti-nuclear protester and you went and yelled at an engineer who runs wind tunnel simulations to design cars, they would see this as strange and unfair. This is true even though there might be some dual use where aerodynamics simulations are also important for designing nuclear missiles.

I understand your point. But I think 'dual use' problems are likely to be very common in AI, just as human intelligence and creativity often have 'dual use' problems (e.g. Leonardo da Vinci creating beautiful art and also designing sadistic siege weapons).

Of course AI researchers, computer scientists, tech entrepreneurs, etc may see any strong regulations or moral stigma against their field as 'strange and unfair'. So what? Given the global stakes, and given the reckless approach to AI development that they've taken so far, it's not clear that EAs should give all that much weight to what they think. They do not have some inalienable right to develop technologies that are X risks to our species.

Our allegiance, IMHO, should be to humanity in general, sentient life in general, and our future descendants. Our allegiance should not be to the American tech industry - no matter how generous some of its leaders and investors have been to EA as a movement.

The graphs above indicate there is no consensus in the industry that AI is on the road to inevitable catastrophe, as the graphs themselves above indicate. The median researcher still considers the field a net positive. But let's set that aside for now and talk only about AI doomers.

Most researchers predicting bad outcomes also have high confidence that they themselves exiting the industry would do nothing to prevent bad outcomes. Somebody will get the bomb first. The day that person gets the bomb, unless you're a 100% doomer, humanity's chances are better the more "alignment-ready" the person who has it is, and if you had to pick an entity to receive the bomb today you could easily do worse than than OpenAI. At least they would have the good sense to turn it off before deciding to do anything else dumb with it.

The "other actors aren't here yet" argument is literally just a punt. They won't stay behind forever. When they catch up, we'll be in the exact same boat, except with the "overwhelming tech lead by institutions nominally pursuing alignment" solutions closed out of the book, a net loss in humanity's chances of survival however thin you think that slice is.

The notion that people simply haven't "taken a step back, reassessed, and rethought their position" ascribes a breathtaking amount of NPC-quality to people in the field, as if they somehow manage to believe in an impending apocalypse and still not spend any time thinking about it. The reason that doomers don't quit the industry themselves, a few deranged cultists aside, is the same reason people have never succeeded into baiting Yudkowsky into endorsing anti-AI terrorism: the impact you have on the final outcome is somewhere between net negative and net zero, as you will inevitably be replaced with another researcher who cares even less about alignment.

The only way quitting the industry actually leads to a better outcome is if you decide that the game is already 100% lost, you only want to maximize years of ignorant bliss before the fall, and you're certain that your competence is so high and your persuasive power so low relative to replacement that you personally quitting represents a net delay on the doom clock. The same argument applies, rescaled, to individual organizations themselves backing out of the game. There's a reason very few people think you can put the genie back in the bottle.

Do you think it's a serious enough issue to warrant some...not very polite responses?

Maybe it would be better if policy makers just go and shut AI research down immediately instead of trying to make reforms and regulations to soften its impact?

Maybe this information (that AI researchers themselves are increasingly pessimistic about the outcome) could sway public opinion enough to that point?

Just as anti-AI violence would be counter-productive, in terms of creating a public backlash against the violent anti-AI activists, I would bet (with only low-to-moderate confidence) that an authoritarian government crackdown on AI would also provoke a public backlash, especially among small-government conservatives, libertarians, and anti-police liberals.

I think public sentiment would need to tip against AI first, and then more serious regulations and prohibitions could follow. So, if we're concerned about AI X-risk, we'd need to get the public to morally stigmatize AI R&D first -- which I think would not be as hard as we expect.

I think we're at the stage now where we should be pushing for a global moratorium on AGI research. Getting the public on board morally stigmatizing it is an important part of this (cf. certain bio research like human genetic engineering).

I suspect that all three political groups (maybe not the libertarians) you mentioned could be convinced to turn collectively against AI research. Afterall, governmental capacity is probably the first thing that will benefit significantly from more powerful AIs, and that could be scary enough for ordinary people or even socialists.

Perhaps the only guaranteed opposition for pausing AI research would come from the relevant corporations themselves (they are, of course, immensely powerful. But maybe they'll accept an end of this arms race anyway), their dependents, and maybe some sections of libertarians and progressives (but I doubt there are that many of them committed to supporting AI research).

The public opinion is probably not very positive about AI research, but also perhaps a bit apathetic about what's happening. Maybe the information in this survey, properly presented in a news article or something, could rally some public support for AI restrictions.

Public sentiment is already mostly against AI when public sentiment has an opinion. Though its not a major political issue (yet) so people may not be thinking about it. If it turns into a major political issue (there are ways of regulating AI without turning it into a major political issue, and you probably want to do so), then it will probably become 50/50 due to what politics does to everything.

How should we think about the 17% response rate to this survey? Is it possible that researchers who are more concerned about alignment are also more likely to complete the survey?

I'd guess very slightly, yes. I'm not aware of easy ways to get much evidence, unfortunately.

I dream of getting a couple questions added onto a big conference's attendee application form. But probably not possible unless you're incredibly well-connected.

Possible, but likely a smaller effect than you might think because: a) I was very ambiguous about the subject matter until they were taking the survey (e.g. did not mention AGI or risk or timelines) b) Last time (for the 2016 survey) we checked the demographics of respondents against those for a random subset of non-respondents, and they weren't very different.

Participants were also mostly offered substantial payment for taking the survey ($50 usually, for a ~15m survey), in part in the hope of making payment a larger motivator than desire to express some particular view, but I don't think payment actually made a large difference to the response rate, so probably failed have the desired effect on possible response bias.

It would be cool to give this survey to top AI forecasters and see what the corresponding graphs look like. E.g. get superforecasters-who-have-forecast-on-AI-questions, or maybe top metaculus users, etc.

I would find it fascinating to see this data for the oil and gas industry. I would guess that far fewer people in that industry think that their work is causing outcomes as bad as human extinction (presumably correctly), and yet they probably face more opprobrium for their work (at least from some left-leaning corners of the population).

There are a few obvious flaws in interpreting the survey as is:

Anthropic's write up, afaik, is a nuanced take and may be a reasonable starting point for an informed and calibrated take towards AI research.

I usually don’t engage with AI takes here because it is a huge echo chamber in here but these are my two cents!

Disagree-voting for the following reasons:

I think Metaculus does a decent job at forecasting, and their forecasts are updated based on recent advances, but yes, predicting the future is hard.