We are grateful to Anneke Pogarell, Birte Spekker, Calum Calvert, Catherine Low, Joan Gass, Jona Glade, Jonathan Michel, Kyle Lucchese, and Sarah Pomeranz for conversations and feedback that significantly improved this post. Any errors, of fact or judgment, remain our entirely own.

Summary

When prioritising future programs in EA community building, we currently lack a quantitative way to express underlying assumptions. In this post, we look at different existing approaches and present our first version of a model. We intended it to make Back-of-the-envelope (BOTEC) estimations by looking at an intervention (community building or marketing activity) and thinking about how it might affect participants on their way to having a more impactful life. The model uses an estimation of the average potential of people in a group to have an impact on their lives as well as the likelihood of them achieving it. If you’d like only to have a look at the model, you can skip the first paragraphs and directly go to Our current model.

Epistemic Status

We spent about 40-60 hours thinking about this, came up with it from scratch as EA community builders and are uncertain of the claims.

Motivation

As new co-directors of EA Germany, we started working on our strategy last November, collecting the requests for programs from the community and looking at existing programs of other national EA groups. While we were able to include some early on as they seemed broadly useful, we were unsure about others. Comparing programs that differ in target group size and composition as well as the type of intervention meant that we would have to rely on and weigh a set of assumptions. To discuss these assumptions and ideally test some of them out, we were looking for a unified approach in the form of a model with a standardised set of parameters.

Impact in Community Building

The term community building in effective altruism can cover various activities like mass media communication, education courses, speaker events, multi-day retreats and 1-1 career guiding sessions. The way we understand it is more about the outcome than the process, covering not only activities that focus on a community of people. It could be any action that guides participants in their search for taking a significant action with a high expected impact and to continue their engagement in this search.

The impact of the community builder depends on their part in the eventual impact of the community members. A community builder who wants to achieve high impact would thus prioritise interventions by the expected impact contribution per invested time or money.

Charity Evaluators like GiveWell can indicate impact per dollars donated in the form of lives saved, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) reduced or similar numbers. If we guide someone to donate at all, donate more effectively and donate more, we can assume that part of the impact can be attributed to us.

For people changing their careers to work on the world's most pressing problems, starting charities, doing research or spreading awareness, it’s harder to assess the impact. We assume an uneven impact distribution per person, probably heavy-tailed. Some people have been responsible for saving millions, such as Norman Borlaug or might have averted a global catastrophe like Stanislav Petrov.

Existing approaches

Marketing Approach: Multi-Touch Attribution

Finding the people that could be interested in making a change to effective altruistic actions, guiding them through the process of learning and connecting while keeping them engaged up to the point where they take action and beyond is a multi-step process. We expect most people to have multiple touchpoints with content and people along the way, like media, the EAD website, newsletter, books, local community events, fellowships, EAG(x) or 1-1s. Each is expected to affect the person’s engagement and the likelihood of taking the next step in larger commitments. Looking back at a person's steps until they made a large change, we can ask them what share of the decision they attribute to the touchpoints along the way. In marketing, this is called multi-touch attribution.

We describe a formula for calculating the impact that could be attributed to us as community builders. Still, ultimately, we conclude that it needs more work before it is ready to be used. After finalising our strategy, we learned that Open Phil had already worked on a more detailed model on similar principles two years ago.

Open Philanthropy: Influences on Longtermist Careers

In 2020, Open Phil conducted a survey of about 200 people working in longtermist areas, querying them in detail about community-building interventions that were important for them getting more involved and helping them have more impact. The respondents mentioned influences in free text, selected them from an existing list and gave them impact points. Additionally, the survey designers gave weights to the respondents according to the expected altruistic value of their careers on a scale of 1-1,000. This resulted in a list of interventions that could be ranked by their importance to the set of people.

While the survey has many influence factors, the level of detail seems insufficient to make informed predictions in comparing interventions within local or national groups: “Local EA groups, including student groups” is listed as one factor without splitting it up into the activities. It is also a descriptive model that looks at the influences on people before 2020. If we want to make assumptions about new interventions, we will need another approach.

80,000 Hours: Leader’s Survey on Value of Employees

A 2018 survey of leaders of EA organisations included a section that asked what donation amount organisations would be willing to sacrifice instead of losing a recent hire. The results were in the millions of dollars for senior hires, and the subsequent discussion led to a clarifying post.

This approach addresses the altruistic impact that people might have in the future.

CEA: Three-Factor Model of Community Building

Among other models, CEA uses “a three-factor model of community building where the amount of good someone can be expected to do is assessed as the product of three factors: resources, dedication and realisation.” In the case of donations, the resources could be a person's income, the dedication, the percentage donated, and the realisation of the effectiveness of the charity the money is donated to. Each of these factors can differ by at least an order of magnitude, and the model can be used to think about which of them to try to influence based on different target groups.

The model seemed very useful to us when looking at individuals taking an impactful action now, like taking the GWWC pledge or donating. For our purpose of comparing different interventions quantitatively based on their future results, we would have had to estimate the three factors before and after an intervention, leading to six parameters. While the CEA model looks at the present values of the factors, we would have had to predict the lifetime impact of someone making a career transition and discounting for them dropping out beforehand.

Ultimately we found the three-factor model to be too complex for our purposes.

CEA: Career Value

In April 2022, the CEA groups team gave a presentation where they estimated the counterfactual value of different actions.

Based on average salaries, times to retirement and drop-off rates, they roughly calculated $70,000 in expected donations for a GWWC pledge.

For a longtermist career, they estimated the number of people working in the field, the amount pledged to longtermist causes at that time and the willingness of organisations to hire a good candidate earlier rather than later. The result was a value of $18 million over the lifetime of a new employee. They noted that this value changed based on the potential contribution of the person and what role they would fill.

For non-longtermist causes, they estimated 10x less counterfactual value as there was less money pledged and cause areas were not as talent constrained. In their presentation, they then tried to tease out intuitions of where community builders should focus if they assumed they were 10% responsible for each action outlined above.

As the presentation is from April 2022, the numbers for career changes would be much lower after the reduction of the money pledged to longtermist cause areas since then.

Our current model

After looking into the existing approaches, we concluded that the level of uncertainty in predictions didn’t warrant a complex model. Reducing the parameters would make it easier to show our assumptions and focus on points where there might be disagreements. On a high level, we’re focusing on:

- Number of people affected by an intervention

- Change of average expected impact per participant

The last part is where it gets tricky, and we will discuss it below. Assuming we have the two parameters, we can calculate the impact change, factor in the costs and prioritise them accordingly.

Expected Impact

We assume people can have very different altruistic impacts. CEA’s article about the three-factor model, describes how each of the three factors could differ by at least one order of magnitude for people in Western countries. The Open Phil Survey uses an impact scale of four orders of magnitude between people working on longtermist causes.

Making sure that we’re guiding people in the right direction of having a high impact and focusing on those with this opportunity seems important. At the same time, we acknowledge that the future impact of people is tough to predict.

Looking at an intervention in community building, we can assume it had a positive impact if the average expected impact of each participant is higher after the intervention than before. In an ideal world, we could take two similar groups of people, apply an intervention on one and then record their impact over their lifetime. The difference between participants in both groups would be the change in expected impact.

For this model, we will assume that expected impact is the product of

- The maximum impact potential of a person over their lifetime

- The likelihood (or expected share) of reaching their impact potential

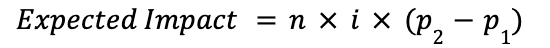

To put it into a formula:

n: Number of participants in the intervention

i: Average impact potential of participants

p1: Likelihood of participants reaching their impact potential before the intervention

p2: Likelihood of participants reaching their impact potential after the intervention

Impact Potential

We define the average impact potential of a group as a fixed numerical value. In an ideal world, every person would have the same potential to have a high altruistic impact. As we look at individual interventions in today’s world, we acknowledge that the impact of people is unevenly distributed. We can affect this number by target group selection. A mass media campaign reaching broad parts of the population is expected to have a lower average impact potential than, for example, a small event only for people already working on highly impactful causes.

Likelihood of Reaching the Impact Potential

The second value we consider is the likelihood (or expected share) of reaching their impact potential. We assume we can affect this through the intervention. Having a career 1-1 with someone might point them in a direction that increases the share of the impact potential they can reach. This can be a value between >0% and 100%.

Cost-Effectiveness

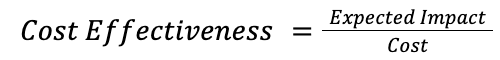

If we estimate the cost of an intervention (money and hours of work), we can calculate the cost-effectiveness:

We can now use this number to compare interventions.

Use Cases

The model can be used to compare different interventions without having to define all of the parameters universally.

Example 1

For example, we could compare the cases of

- Giving an introductory EA talk to a general audience of 100 people

- Giving an introductory EA talk to an audience of 10 entrepreneurs that have just sold their companies

We could assume the likelihood of audience members reaching their altruistic potential increasing through the talk will be similar, and the effort might be the same. In this case, we can ask ourselves if we see the impact potential of the entrepreneurs as more or less than 10x to prioritise the talk.

Example 2

Another example would be comparing two interventions at a local EA group. The group size and the average impact potential will stay the same, whereas

- Intervention 1 is highly engaging and needs 10 hours of preparation time

- Intervention 2 is mildly engaging and needs 1 hour of preparation time

Now we can ask ourselves if we think the percentage point increase of intervention 1 will be 10x higher than for intervention 2 (e.g. 10% to 15% vs 10% to 10.5%) to prioritise.

If we have more interventions, we could develop categories of target groups and estimate their relative average impact. For example, we could look at the general audience in a region, university students, mid-career leaders etc. We could also ask ourselves the current likelihood of them reaching their potential and how much we might affect it.

For younger people with fewer years of education, we might see a lower maximum likelihood even after optimal guidance, as they might still drop out before being able to take an impactful job or being able to donate substantially. At the same time, younger people might have a higher impact potential as they can change their career paths more easily.

Caveats and Uncertainties

This model currently does not address externalities, especially downside risks. We could see vetting against potential harms as a separate phase in the prioritisation process. Additionally, it also does not consider counterfactuals, with some interventions being more likely to happen anyways than others.

Given the high uncertainties, big error bars should be given around all parameters. While our model is designed to help prioritise interventions that help guide individuals to take significant actions, this approach might undervalue building a diverse and resilient EA community. The post “Doing EA Better” argues that quantifying might lead to worse results and weaken collective epistemics. We agree that this is a possibility and that it is easy to place too much emphasis on quantitative predictions that are merely based on intuition. Perhaps intuition without quantification might be better suited, or we might need models that let us formulate hypotheses so we can validate them.

We’re not researchers but community builders that need a framework to think about our decisions and will have to prioritise our next interventions soon. Given these constraints, we think it’s more useful to publish our current thoughts after a couple of weeks than to spend more time working on them alone. We’re curious to get feedback and are open to the possibility that this model won’t be useful to others or even to us after thinking about it more.

Sorry in advance for the long comment, I am attempting to explain statistics concepts in a helpful/accessible way to a broad audience, because I think it's really important to consider uncertainty well when we make important decisions.

While I love the idea of a BOTEC model for comparing impact of community building interventions, this seems like a formula that is likely susceptible to the flaw of averages. The flaw of averages is the idea that systematic errors occur when we base calculations on the average (expected value) of uncertain inputs, rather than the entire distribution of possible inputs.

So when in your formula you use i (average impact potential of participants), that seems like a potentially major oversimplification of the reality that you might see a wide range of impact potentials within a certain intervention. Relying on averages in this way is known to actually mislead decision making (fields like risk management need to pay attention to this, a specific example is flood damage modeling, but it crops up all over the place).

For a simple example: say you are doing a fundraiser targeting students and parents (I'm using $ because it's easy to quantify and understand). You expect to reach 90 students and only 10 parents. You expect the likelihood increase for making a donation for students is 0.8, and the likelihood increase for donations from parents is 0.4.

The vast majority of participants are students, so you decide to classify your "average giver" as a student (since student vs parent are discrete categories). Having decided that the "average" target of the fundraiser is other students, you predict that the average participant who makes a donation will give $10. So if you convince 100 people to donate, by the formula, your expected value is $10*100*0.8=$800. Your predicted average donation is $8.

However, the reality is a bit different, because maybe your fundraiser reaches 90 students and 10 parents. Parents in this scenario have much greater disposable income, such that the parents who donate will each give $100. So now, your expected value is $10*90*0.8+$100*10*0.4=$1,120. Your actual average donation is now $11.2 per person, which is a 40% increase over your predicted average donation.

This is a simplified/exaggerated example of how heavy tailed distributions (which can be thought of as the technical term for black swan events) can distort statistics. Quantities like income and wealth are heavy tailed in reality. I think you could make the case that actual impact as an outcome (vs impact potential) is heavy tailed as well. Open Philanthropy seems to agree with this based on their Hits-based Giving approach. And you actually mention that the"Open Phil Survey uses an impact scale of four orders of magnitude between people working on longtermist causes".

"The problem with observations or events from a heavy tail is that even though they are frequent enough to make a difference, they are rare enough to make us underestimate them in our experience and intuitions." This article "Heavy Tails and Altruism: When Your Intuition Fails You" has more detail on the topic.

Maybe your formula could allow for summation of different projected classes of participants? This could help it account for lower-likelihood/lower frequency, but higher-impact-potential participants. Since interventions could vary significantly in terms of relevance of these "black swans," accounting for them seems important to me. You may be hinting at this approach in your explanation of example 2.

Given that we care more about actual impact than impact potential, I personally feel pretty cautious about promoting a movement-wide approach to community building that might limit creativity/innovation/experimentation, and that potentially favors narrowing down over broadening outward.

P.S. - I want to acknowledge that it's much easier to critique other people's work than to attempt something from scratch. So I also wanted to thank you for writing this up and sharing it! I like the overall idea, enjoyed learning about the existing approaches thanks to your research, and appreciate you working on community building so thoughtfully. Thank you!

Strongly agree with your comment. I noticed the same thing while reading the post. The factor i for average impact per participant is really handwavy; I think impact per person varies widely (even within preselected groups, e.g. 80k's target audiences such as Numberphile youtube viewers) and this makes the model less useful at this level of simplification.

Here is a squiggle model which addresses some of these concerns

To execute it, you can paste it here: <https://www.squiggle-language.com/playground>.

Thanks for writing up your thinking on this, and also more in general for doing the hard work of community building. 🙌

I think Tess makes good points in their comment about the huge amounts of uncertainty contained in that impact potential factor, and I would go a step further and say:

The factor i is a red herring, and it is harmful for community building to try and predict it.

Using it to decide who is "most worthy of outreach" is in direct conflict with core strenghts of the EA community: cause-neutrality and openness to neglected approaches to making the world a better place.

What should be done instead?

Aim to build a broad, diverse community that is welcoming and non-judgemental and accurately communicates EA ideas to a large audience. Build a community that you would want to be part of. Does this mean abandoning quantitative measures? No, we can still measure if we achieve our goals:

The high impact potential people (those mythical creatures) will find their way once they have come in contact with an accurate representation of EA ideas. It's not the job of community builders to identify and guide them (because they can't), their job is to build an awesome community that communicates EA ideas with high fidelity so that many people come in contact with good first hand accounts of these ideas instead of simplified straw-man versions of EA in take-down articles about scandals in the EA community.

As a community member, reading this kind of marketing language being applied to me is kind of uncomfortable. I want to be enabled, not persuaded.

This general approach still makes sense, so I think it should still be applied when doing outreach or planning events. But please don't forget there are people on the other side.

It's important that community members feel valued even if they don't seem likely to have massive impact!

I agree that community members should feel valued. At the same time, I don't think this model changes much in that services for community members have always been discriminatory. Not everyone is accepted for 80k calls, EAG(x) conferences or retreats. While it's important to have open local groups, I think having clearer priorities on national or international services seems less exclusive.

I agree that persuasion frames are often a bad way to think about community building.

I also agree that community members should feel valuable, much in the way that I want everybody in the world to feel valued/loved.

I probably disagree about the implications, as they are affected by some other factors. One intuition that helps me is to think about the donors who donate toward community building efforts. I expect that these donors are mostly people who care about preventing kids from dying of malaria, and many donors also donate lots of money towards charities that can save a kid’s like for $5000. They are, I assume, donating toward community building efforts because they think these efforts are on average a better deal, costing less than $5000 for a live saved in expectation.

For mental health reasons, I don’t think people should generally hold themselves to this bar and be like “is my expected impact higher than where money spent on me would go otherwise?” But I think when you’re using other peoples altruistic money to community build, you should definitely be making trade offs, crunching numbers, and otherwise be aiming to maximize the impact from those dollars.

Furthermore, I would be extremely worried if I learned that community builders aren’t attempting to quantify their impact or think about these things carefully (noting that I have found it very difficult to quantify impact here). Community building is often indistinguishable (at least from the outside) from “spending money on ourselves” and I think it’s reasonable to have a super high bar for doing this in the name of altruism.

Noting again that I think it’s hard to balance mental health with the whacky terrible state of the world where a few thousand dollars can save a life. Making a distinction between personal dollars and altruistic dollars can perhaps help folks preserve their mental health while thinking rigorously about how to help others the most. Interesting related ideas:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/3p3CYauiX8oLjmwRF/purchase-fuzzies-and-utilons-separately https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zu28unKfTHoxRWpGn/you-have-more-than-one-goal-and-that-s-fine