Key Takeaways

- Many theories of welfare imply that there are probably differences in animals’ welfare ranges. However, these theories do not agree about the sizes of those differences.

- The Moral Weight Project assumes that hedonism is true. This post tries to estimate how different our welfare range estimates could be if we were to assume some other theory of welfare.

- We argue that even if hedonic goods and bads (i.e., pleasures and pains) aren't all of welfare, they’re a lot of it. So, probably, the choice of a theory of welfare will only have a modest (less than 10x) impact on the differences we estimate between humans' and nonhumans' welfare ranges.

Introduction

This is the third post in the Moral Weight Project Sequence. The aim of the sequence is to provide an overview of the research that Rethink Priorities conducted between May 2021 and October 2022 on interspecific cause prioritization. The aim of this post is to suggest a way to quantify the impact of assuming hedonism on welfare range estimates.

Motivations

Theories of welfare disagree about the determinants of welfare. According to hedonism, the determinants of welfare are positively and negatively valenced experiences. According to desire satisfaction theory, the determinants are satisfied and frustrated desires. According to a garden variety objective list theory, the determinants are something like knowledge, developing and maintaining friendships, engaging in meaningful activities, and so on. Now, some animals probably have more intense pains than others; some probably have richer, more complex desires; some are able to acquire more sophisticated knowledge of the world; others can make stronger, more complex relationships with others. If animals systematically vary with respect to their ability to realize the determinants of welfare, then they probably vary in their welfare ranges. That is, some of them can probably realize more positive welfare at a time than others; likewise, some of them can probably realize more negative welfare at a time than others. As a result, animals probably vary with respect to the differences between the best and worst welfare states they can realize. The upshot: many theories of welfare imply that there are probably differences in animals’ welfare ranges.

However, theories of welfare do not obviously agree about the sizes of those differences. Consider a garden variety objective list theory on which the following things contribute positively to welfare: acting autonomously, gaining knowledge, having friends, being in a loving relationship, doing meaningful work, creating valuable institutions, experiencing pleasure, and so on. Now consider a simple version of hedonism (i.e., one that rejects the higher / lower pleasure distinction) on which just one thing contributes positively to welfare: experiencing pleasure. Presumably, while many nonhuman animals (henceforth, animals) can experience pleasure, they can’t realize many of the other things that matter according to the objective list theory. Given as much, it’s plausible that if the objective list theory is true, there will be larger differences in welfare ranges between many humans and animals than there will be if hedonism is true.

For practical and theoretical reasons, the Moral Weight Project assumes that hedonism is true. On the practical side, we needed to make some assumptions to make any progress in the time we had available. On the theoretical side, there are powerful arguments for hedonism. Still, those who reject hedonism will rightly wonder about the impact of assuming hedonism. How different would our welfare range estimates be if we were to assume some other theory of welfare?

In the rest of this post, we argue that while assuming hedonism makes a difference to welfare range estimates, it makes a surprisingly small difference—likely less than 10x. Our central claim here is that even if hedonic goods and bads (pleasures and pains) aren’t all of welfare, they’re a lot of it.

Tortured Tim

The task here is to determine the impact of assuming hedonism on welfare range estimates. We don’t need to consider all possible theories of welfare to do this. Instead, we need to identify a theory that’s plausible and can serve as an upper bound. That is, we need to identify a theory of welfare that meets two conditions: first, those concerned with relative welfare range estimates would be willing to assign it a reasonably high credence; second, of the theories meeting the first condition, it supports the largest differences in welfare range estimates.

These conditions are fuzzy; we won’t try to make them precise here. Moreover, we won’t dwell on the challenge of showing that a given theory meets these conditions. Instead, we’ll simply propose a candidate that seems promising and argue from there: namely, the garden variety objective list theory that we mentioned earlier. Given as much, our strategy is to assess the impact that the choice between hedonism and our garden variety objective list theory is likely to have on our welfare range estimates for humans. Then, we can extrapolate to animals.

Round 1: Can Non-Hedonic Goods Outweigh Hedonic Bads?

Our garden variety objective list theory needs to specify how much the various items on the list contribute to an individual’s welfare range. Recall: our objective list theory says that there are many things that are good for individuals, including friendship, romantic love, acquiring knowledge, engaging in theoretical contemplation, doing meaningful work, developing practical skills, and so on. Now imagine Tortured Tim, an individual who is experiencing extraordinarily intense physical suffering. Nevertheless, he may have many other goods in his life: friendship, romantic love, knowledge, practical skills, and so on. However, it seems highly implausible that these goods put Tortured Tim into a net positive welfare state: no matter how valuable they are, they aren’t so valuable as to outweigh the welfare costs of intense physical suffering.

Imagine the objective list theorist denying this. Then, the objective list theorist would be committed to saying that it would be prudentially rational for Tim to choose to extend his life by a day of torture rather than die a day sooner, as long as that wouldn’t affect the other goods in his life. Or, if the arc of a life matters, the objective list theorist would be committed to saying that it would be prudentially rational for Tim to choose days of torture now for an equivalent number of normal days tacked onto the end of his life. It seems obvious, though, that it would not be prudentially rational for Tim to make either choice.

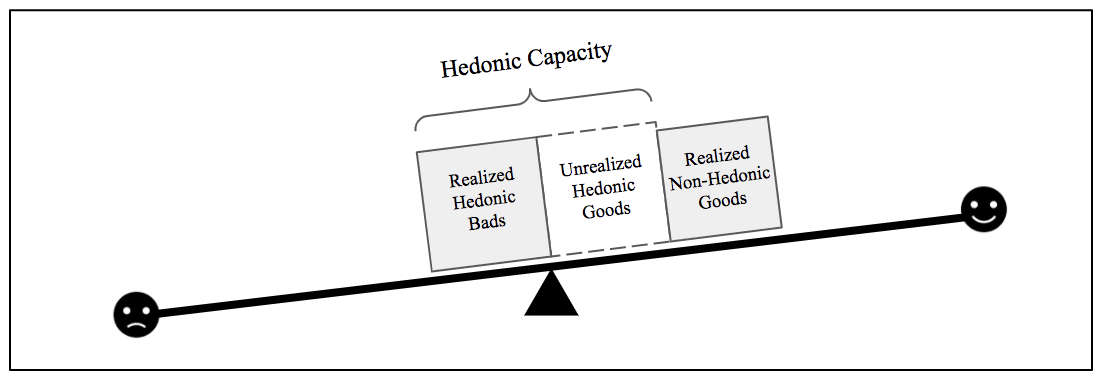

Let’s grant, then, that the non-hedonic goods in Tim’s life don’t put Tim into a net positive welfare state. Let’s suppose further that welfare ranges are symmetrical around the neutral point—that is, individuals can be made as well off as they can be made badly off. It follows that those non-hedonic goods, in the aggregate, increase Tim’s welfare less than 50% of the hedonic portion of his welfare range (his “hedonic capacity,” for short). That is, if the positive contributions of the various non-hedonic items on the objective list don’t jointly outweigh Tim’s suffering—i.e., they leave him in a net negative welfare state—then they aren’t contributing more than half of that portion of Tim’s welfare range that’s grounded in his capacity to experience positive and negative affective states. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Tortured Tim

If that’s right, then we have a data point that’s relevant to our initial question: just based on the above, it looks like the choice of a theory of welfare won’t change our welfare range estimates by more than a factor of 1.5. That is, suppose that if hedonism is true, then chickens have a welfare range of 10 welfare units. It would follow that if our objective list theory is true, their welfare range will be less than 15 welfare units (depending on how well they can realize the relevant objective goods). In other words, when we "tack on" the portion of the welfare range associated with unrealized non-hedonic goods, it doesn't change Tim's total welfare range all that much.

Before going any further, let’s pause to note that nothing said thus far entails that interspecific variation in welfare ranges is limited to a factor of 1.5. To see why not, let’s assume that given hedonism, chickens have a welfare range of 10 welfare units, whereas given our objective list theory, they have a welfare range of 12. Now consider the abilities that permit securing various non-hedonic goods. For all we’ve said, those may significantly enhance an individual’s hedonic capacities too. That is, it could work out that the cognitive capacities that permit, say, theoretical contemplation also permit individuals to feel pleasures and pains more intensely than those without such capacities.

However, if hedonic capacities are enhanced by the same capacities that matter for securing various non-hedonic goods, then hedonism might imply that humans have a welfare range of 50, whereas given our objective list theory, they might have a welfare range of 74. So, the choice between hedonism and objective list theory could, in principle, be the difference between saying that humans have five times chickens’ welfare range vs. saying that humans have roughly seven times their welfare range. Still, there’s an intraspecific cap. Suppose that hedonic capacities are enhanced by the same capacities that matter for securing various non-hedonic goods. Then, given some set of empirical facts, the shift from one theory of welfare to another shouldn’t affect our estimate of one species’s welfare range by a factor greater than 1.5.

Tortured Tim, Round 2: Can Hedonic Bads Compromise Non-Hedonic Goods?

All that said, there’s a problem with our estimate. Our description of Tim’s case assumes that Tim can face extraordinary suffering while retaining all the relevant non-hedonic goods. However, it could well be that at least some non-hedonic goods are compromised as suffering increases. For instance, if exercising your autonomy enhances welfare and Tim is suffering to the point that he can’t exercise his autonomy, then he lacks that non-hedonic good.

By way of reply, let’s first note that plausible though this observation may be, it doesn’t seem to apply to every non-hedonic good. You can still have friends while being tortured; you can still have knowledge; indeed, you can actually be doing meaningful work by being tortured, as might be true of martyrs in the right (horrible) circumstances. So, while this observation may show that we’ve underestimated the ceiling on the difference that non-hedonic goods can make to welfare ranges, there are limits to its significance.

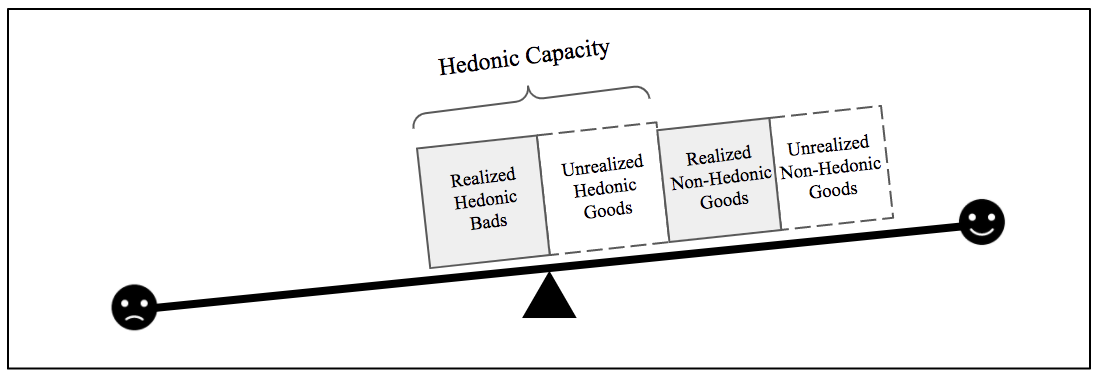

The second thing to say is more concessive. Suppose that there are 11 items on the objective list, with hedonic goods being one of them, and suppose that of the 10 remaining, half the items are zeroed out due to Tim’s suffering. Finally, suppose that all 10 of those remaining items make equal contributions to welfare. Originally, we concluded that if all the non-hedonic goods don’t outweigh Tim’s suffering, then they increase Tim’s welfare by less than 50% of his hedonic capacity—that is, his ability to have those goods means that his total welfare range is no more than 1.5 times his hedonic capacity. With these new assumptions, we can conclude that his ability to have all the objective goods no more than doubles his welfare range. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Factoring in Unrealized Non-Hedonic Goods

However, the third thing to say is that we’ve been charitable—and perhaps too charitable—in our estimate of the contribution of non-hedonic goods. For what it’s worth, we don’t think it’s plausible that those goods get Tim anywhere near a net positive welfare state. His net welfare state remains very, very low even if he has a significant number of non-hedonic goods. So, if we suppose that those non-hedonic goods do far less to offset Tim’s suffering, it follows that even if some non-hedonic goods are compromised as suffering increases, non-hedonic goods still make a much smaller contribution to individuals’ welfare ranges than hedonic bads—perhaps not even enough to justify our original, factor-of-1.5 estimate.

Round 3: What about Non-Hedonic Bads?

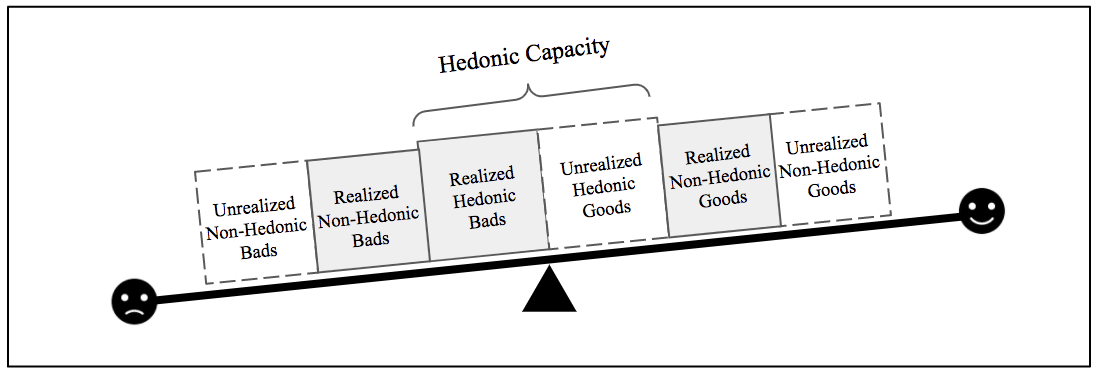

Unfortunately, there’s another problem with our estimate. Thus far, we’ve been ignoring non-hedonic bads. For instance, Tortured Tim has been tortured, which means that he’s been violated. Perhaps it’s objectively bad to be violated. If so, then we’ve been ignoring factors that can drag Tim’s welfare level down further, which means that his welfare range is larger.

How much larger, of course, depends on the list of objective bads and their relative weights. Let’s assume, however, that the non-hedonic bads mirror the non-hedonic goods—which may not be true, but seems like a friendly concession. That is, let's assume that if there are 10 non-hedonic goods, then there are 10 non-hedonic bads. Moreover, let's assume that Tim isn’t realizing every non-hedonic bad simply in virtue of being tortured. Then, factoring in both non-hedonic goods and bads might triple his total welfare range relative to his hedonic capacity. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3: Factoring in Realized and Unrealized Non-Hedonic Bads

Of course, in saying this, we’re ignoring the point we made at the end of the last section: namely, that we’ve been too charitable in our estimate of the contribution of non-hedonic goods, which suggested that doubling was too high an estimate. If that’s right, then tripling is too high an estimate as well.

Applying Tortured Tim to animals

Still, let’s suppose that tripling is correct. Let’s also suppose that welfare invariabilism is true, according to which the same theory of welfare is true of every welfare subject. So, to illustrate, if our garden variety objective list theory is true of humans, then it’s true of all nonhumans. (This is a friendly assumption: if variabilism is true, we might not get any differences in welfare ranges at all.) Given invariabilism, we can say that if the choice between a simple version of hedonism and an objective list theory wouldn’t affect our estimate of humans’ welfare range by more than 3x, it shouldn’t affect our estimates of nonhumans’ welfare ranges by more than 3x.

Again, this is not the same thing as saying that interspecific variation in welfare ranges is limited to 3x. For all we’ve said here, many nonhumans may have much smaller hedonic capacities than many humans. If chickens, for instance, have just 0.1x humans’ hedonic capacity, then the choice between hedonism and an objective list theory could be the difference between the conclusion that chickens have 0.1x humans’ welfare range (given hedonism) and ~0.03x humans’ welfare range (given our objective list theory). So, the point is about the impact of theories of welfare on welfare range estimates. We aren’t making any claims here about welfare range estimates themselves, nor even trying to bound them.

Conclusion

Prior to investigating this issue, we would have guessed that disagreements about the correct theory of welfare could cause welfare range estimates to differ by orders of magnitude. If we’ve drawn the right lesson from poor Tortured Tim, that simply isn’t true. We suggest that, compared to hedonism, an objective list theory might 3x our estimate of the differences between humans’ and nonhumans’ welfare ranges. But just to be cautious, let’s suppose it’s 10x. While not insignificant, that multiplier makes it far from clear that the choice of a theory of welfare is going to be practically relevant. To see this, recall that Open Philanthropy once estimated that "[if] you value chicken life-years equally to human life-years, this implies that corporate campaigns do about 10,000x as much good per dollar as top [global health] charities." We've argued that the "discount" from switching to an objective list theory will be relatively small. So, while it might matter alongside other ways of "discounting" chicken welfare, it would be surprising if a theory of welfare could alter the outcome of such analyses on its own.

Acknowledgments

This research is a project of Rethink Priorities. It was written by Bob Fischer. Thanks to Jason Schukraft, Adam Shriver, Rachel Norman, Martina Schiestl, Alex Schnell, and Anna Trevarthen for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this post. Thanks to Catarina Kissinger for the visuals. If you’re interested in RP’s work, you can learn more by visiting our research database. For regular updates, please consider subscribing to our newsletter.

Thanks for the interesting post! I basically agree with the main argument, including your evaluation of the Tortured Tim case.

To also share one idea: I wonder whether a variation of the famous experience machine thought experiment can be taken to elicit a contrary intuition to Tortured Tim and whether this should decrease our confidence in your evaluation of the Tortured Tim case. Suppose a subject (call her "Sarah") can choose between having blissful experiences in the experience machine and having a moderately net-positive live outside of the machine, involving a rather limited amount of positive prudential (experiential and non-experiential) goods. I take it some (maybe many? maybe most?) would say that Sarah should (prudentially) not choose to enter the machine. If rather few non-experiential goods (maybe together with some positive experiences) can weigh more than the best possible experiences, this suggests that non-experiential goods can be very important, relative to experiential goods.

A possible reply would be that most of the relevant non-experiential goods might not be relevant, as they might be things like “perceiving reality” or “being non-deceived” which all animals trivially satisfy. But, in response, one may reply that the relevant non-experiential good is, e.g., the possession of knowledge which many animals may not be capable of.

In general, in these kinds of intuitive trade-offs negative experiences seem more important than positive experiences. Few would say that the best non-experiential goods can be more important than the most terrible suffering, but many would say that the best non-experiential goods can be more important than purely the most blissful experiences. Thus, since, in the decision-contexts you have in mind, we mostly care about negative experiences, i.e. animal suffering, this objection may ultimately not be that impactful.

Strong upvoted, I think this is a really excellent point.

Thanks for your comment, Leonard. I guess I'd want to push your case a bit further. Imagine that Sarah enters the experience machine and is maxed out with respect to hedonic goods. Would the objective list theorist want to say that her life is bad on balance? Is it actually net negative? Presumably not. Her life might be much less good than it could be, but would still be positive on balance. If that's right, then that's exactly what we'd expect based on the Tortured Tim case: we get symmetry with respect to the impacts of non-hedonic goods. On Tim's side, they can't make him net positive; on Sarah's side, they can't make her net negative. Either way, they play a role in total welfare that's no greater than the role played by hedonic goods and bads.

Thanks for the reply, I think it helps me to understand the issue better. As I see it now, there are two conflicting intuitions:

1. Non-hedonic goods seem to not have much weight in flipping a life from net-negative to net-positive (Tortured Tim) or from net-positive to net-negative (The experience machine). That is, Tim seems to have a net-negative life, even though he has all attainable non-hedonic goods, and Sarah in the experience machine has a net-positive life although she lacks all positive non-hedonic goods (or even has negative non-hedonic goods).

2. In the experience machine case, it seems (to many) as if hedonic goods have a lot less weight than non-hedonic goods in determining overall wellbeing. That is, Sarah can have blissful experience (100 on a hedonic scale from -100 to 100) in the machine but would arguably have a better life if she had moderately net-positive experience (say, 10 on the same scale) combined with the non-hedonic goods contained in almost any ordinary life.

If you interpret the experience machine case as involving negative non-hedonic goods, then the first intuition suggests what you say: that non-hedonic goods “play a role in total welfare that's no greater than the role played by hedonic goods and bads”. However, the second intuition does suggest precisely the opposite, it seems to me. If a moderate number of incompletely realized non-hedonic goods has a higher positive impact on welfare than perfectly blissful experience, then this suggests that non-hedonic goods play a more important role in welfare than hedonic goods, in some cases.

Appreciate your pushing this forward, Leonard. I guess I’m still not seeing why this is a problem for the main line of argument. I‘m thinking of goods and bads as being straightforwardly additive. So it’s true that, if an objective list theory is true, Sarah may have sufficient reason not to enter the machine even if it would max her out hedonically, but it doesn’t follow from that that hedonic goods have a lot less weight than non-hedonic goods in determining overall wellbeing. Suppose that Sarah‘s hedonic scale goes from -100 to 100, as you suggested, and her total wellbeing scale goes from -300 to 300, as I’ve suggested (3x). Then, she’s potentially leaving a lot of value on the table if she goes into the machine, as she’d get all that hedonic value (100) but none of the non-hedonic value (which represents an additional 200 possible welfare units). In such circumstances, it’s prudential rational for her to take a lower hedonic level (say, 25) to get even half the possible non-hedonic benefits (100), as that makes her better off overall (125 vs. 100).

Your way of further fleshing out the example is helpful. Suppose we think that Sarah has some, but below average non-hedonic benefits in her live (and expects this for the future) and that she should nonetheless not enter the machine. The question would then come down to: In relative terms (on a linear scale), how close is Sarah to getting all the possible non-hedonic value (i.e., does she get 50% of it, or only 10%, or even less)? The farer she is away from getting all possible non-hedonic value, the more non-hedonic value contributes to welfare ranges. However, at this point, it is hard to know what the most plausible answer to this question is.

Thanks very much for writing this, I think you did a very clear job with the graphics and scenarios laying out the considerations.

I do wonder though if you have somewhat stacked the deck in favour of the hedonist account here:

This is a pretty extreme ('extraordinarily intense') pain scenario, vs fairly pedestrian goods like 'friendship'. I think some people's intuitions might be quite different in this sort of scenario:

In this example, where I've tried to fill in the positive good examples to have a higher, more 'extraordinarily intense' magnitude, and be more specific, it does seem pretty plausible to me that Tim is experiencing positive welfare at that moment. It's definitely not the case that I would feel qualified, as an outside to observer, to contradict Tim's claim that this is a very positive experience for him.

Great case, Larks! Thanks for sharing.

I feel the force of this. However, I confess that as you rachet up the intensity of his suffering, I become less and less convinced that he's net positive. I do think that the goods you're describing can outweigh a lot of pain. But when I imagine hypothermia setting in--shivering uncontrollably, with muscles spasming and aching--I lose the sense that he's net positive.

But suppose you disagree and think he's net positive even then. I guess my question is: how positive is he? Do you still think it's a borderline case? If so, then we're still learning a lot about the relationship between Tim's hedonic and non-hedonic welfare capacity. And that's probably enough for the main conclusion of the post, which is that a different theory of welfare wouldn't make more than an order of magnitude difference.

Thanks for your response!

In general I think it is hard to judge how much better one scenario is than another. But one way of getting at this is to add extra costs to one side of the scale. I think if you told me Tim had paid $10,000 to go on this trip, my evaluation of whether or not it was a good idea wouldn't significantly change vs if he paid $20,000, or if it was free. Similarly, my evaluation also wouldn't change a lot if he was hungry. So that makes me think my intuition is this is a pretty positive experience.

I can certainly believe this is a scenario where our fundamental intuitions just differ and there's not much more to say on the topic.

I wonder if your original description is compatible with "extraordinarily intense physical pain". Or, maybe it could still be extraordinary, but well within what's bearable and far from torture. Could he carry on a conversation with his high school sweetheart if the pain were intense enough, or be excited to marry her, or think about his promise to his grandfather? When pain reaches a certain level of intensity, I expect it to be very difficult to focus attention on other things. And, to the extent that he is focusing his attention on other things and away from the pain, the pain's hedonic intensity is reduced.

Imagine he's also or instead having a panic attack. Or, instead of the trip, he's undergoing waterboarding as a cultural rite of passage (with all the same goods, similar ones or greater ones from your original description). How long could the average person be voluntarly waterboarded for any purpose? (EDIT: Or for some personal positive good in particular? I can imagine a sense of duty, e.g. to prevent greater harm to others or harm to loved ones in particular, allowing someone to last a long time, and those may figure into welfare range, but I probably wouldn't describe these in terms of positive goods, or maybe even bads, so that they can't be put on a ratio scale, only an interval scale at most.) These seem intense enough to consume attention. (I honestly don't have much intuitive sense of how painful frostbite can be.)

(I also don't expect added hunger to make much difference to his hedonic welfare in the moment, because he'll be focusing on the much more intense pain. Less sure about financial costs, although those would probably not really affect his welfare during the trip itself.)

Interesting point, thanks for raising.

I worry a bit we might be introducing some confusion here. As far as I am aware, there is disagreement about whether welfare is constuted only by things you can experience (e.g. happiness, pain, pride, excitement, the-feeling-of-being-in-love) or whether it can also include things that you are not directly aware of (e.g. your welfare is reduced by infidelity, even if you are unaware).

If we believe that welfare is only determined by things you can experience, then I agree with you that when the pain is sufficient that he can't direct his attention to the good things, his overall welfare is going to tank. But then I'm not sure it's the pain outweighing the other things; rather, I think it's the pain having a indirect negative effect on his welfare by reducing the goods as well as the direct negative effect. So really now we're comparing a large hedonic value to a smaller non-hedonic value, and hence can't draw any conclusions about the maximum possible size of the two things. Only a scenario in which both are able to be experienced to their greatest extent can allow for such a comparison.

And if welfare is not only determined by things we directly experience? Well, to the extent that things you're not aware of can increase your welfare, I think I would just bite the bullet and say his welfare is indeed high, even if he has trouble focusing on that.

I'm not convinced by this response, but I think this is my best guess.

Seems right, Larks. But I don't set things up this way in the post--or didn't mean to, anyway. I grant that he can have all the non-hedonic goods while being tortured for exactly the reason you mention. But then I still want to say: those non-hedonic goods don't make him net positive.

FWIW, I've given this thought experiment to hard-core objective list theorists and they just bite the bullet, insisting that his life is well worth living even while being tortured. Clearly, then, we aren't going to get agreement based on this thought experiment alone. However, I can't help but think that they're confusing meaningfulness with prudential goodness. I concede that a life could be meaningful in the face of torture--or even precisely because of it in some circumstances. But many meaningful lives are bad for the people who live them, which is partly why they're heroic for continuing them.

Anyway, hard issues!

As one example, I think Richard Yetter Chappell, an objective list theorist, would say torture with maximal non-hedonic goods at the same time would be bad overall per moment: https://rychappell.substack.com/p/a-multiplicative-model-of-value-pluralism

If the pain is so strong he can't focus on and appreciate some good he otherwise would without the pain, isn't this his brain itself deciding the pain is more important? I think this is the cognitive process of motivational salience, which integrates both positive (incentives, pleasure, desire) and negative (aversion, unpleasantness). If (actual or hypothetical/idealized) motivational salience determines importance, then measures of attention during joint exposure experiments are plausibly more reliable for ranking importance than people's statements, because the latter can be subject to additional biases, e.g. believing your commitments, especially to others, are more important than your pain serves your self-image as a good person, partner, friend, child or parent.

You could use more direct measures of motivational salience, including while separately exposed to the good or the pain and this is plausibly closer to what we want to actually measure to determine the scale, but I'd expect the same rankings from measuring attention during joint exposure, all else equal. Similarly if you used some measure of felt (hedonic, desire) intensity directly when separately exposed, although I'm less sure positive and negative would even be commensurable with such a measure. I have read attention disruption is one of the functions of pain, so maybe joint exposure experiments would be negatively biased.

However, if reflective preferences are what matter or are part of it, then for those we would probably use people's (and other animal's) statements or choices. We'd still have to worry about some of the same biases in people, though, but then intense pain may especially interfere with reflection. It's also not clear to me how we would construct an absolute scale to use across even humans, let alone across all animals or possible conscious beings. Even if there isn't one, that doesn't rule reflective preferences out, but then the implications seem much less clear. We might get incomparability between beings or even for the same being over time.

(Actual or hypothetical/idealized) motivational salience, felt intensity and reflective preferences could be different kinds of welfare, possibly incommensurable, if they're determined by very different kinds of valuing systems.

I did have in mind that non-experientialist goods could count, but as you suggest, experientialist goods (or goods that depend on their acknowledgement to count, including non-hedonic ones, so other than pleasure) would probably be weakened during torture, so that could introduce a confounder. The comparison now would be mostly be between hedonic bads and non-experientialist goods.

Another issue is how to determine the weight of non-experientialist goods, especially if we don't want to be paternalistic or alienating. If we do so by subjective appreciation, then it seems like we're basically just turning them back into experientialist goods. If we do so via subjective weights (even if someone can't appreciate a good at the time, they might still insist it's very important and we could infer how good it is for them), its subjective weight could also be significantly reduced during torture. So we still wouldn't necessarily be comparing the disvalue of torture to the maximum value of non-experientialist goods using Tim's judgement while being tortured.

Instead, if we do still want to use subjective weights, we might consider the torture and non-hedonic goods happening at different times (and in different orders?), for equal durations, and ask Tim during the torture, during the non-hedonic goods and at other times whether the non-hedonic goods make up for the torture. If the answers agree, then great. But if they disagree, this could be hard to resolve, because Tim's answer could be biased in each situation: he underweights non-hedonic goods during torture and otherwise while not focusing on them, and he underweights torture while not being tortured.

EDIT: On the other hand, if I tried to come up with a cognitively plausible objective cardinal account of subjective weights and value, I'd expect torture to be able to reach the max or get close to it, and that would be enough to say that negative hedonic welfare can be at least about as bad as goods can be good (in aggregate, in a moment).

"It seems obvious, though, that it would not be prudentially rational for Tim to make either choice."

It is indeed seem obvious - to the other direction! people make this choice, and encourage others to make this choice, all the time!

you can disagree with the mainstream view here, but there is something that is very disconnected from... normal society, in this claim.

The Tortured Toms of the world actually exist, mostly don't want to die, and a lot of time will object at any attempt to describe their life as net-negative.

more then it's look like analysis, it's look like formalized failure in theory of mind, and of just... not knowing people with sucky lives. It's read as if the writers never talked to such person, or read their post in facebook, or read their books.

assume we are right and everyone else is wrong. then, we are right and everyone else is wrong. but why would I assume that?

I find the luck of self awareness in this post really concerning and discrediting.

Maybe another way of handling Tortured Tim in case the torture prevents any non-hedonic goods from counting is to ask whether he should experience a day of torture to get those non-hedonic goods a day more than otherwise. And getting them a day earlier rather than an extra day at the end may also reduce confounding with duties to others, like family or friends. You have more important reasons to maintain relationships than to start them earlier.

There are also of course long-term side effects from torture, but we could also put the torture at the end of his life so that he could make friends/family a day earlier, although this starts to get pretty abstract.

Also, this wouldn't necessarily change the conclusion, but maybe the loss of a relationship/a loved one (or another non-hedonic good) is also a non-hedonic bad rather than just the loss of a non-hedonic good or involves some kind of worseness that is only comparative, neither more/stronger bads nor less/weaker goods. Then undergoing a day of torture to extend the life of a loved one (or multiple) by one day may be rational from a "selfish" point of view, although I'd still guess it wouldn't be.

One possibility in favour of non-hedonic values mattering much more could be internalizing an individual's ethical views, obligations or rankings of social outcomes as their own welfare. For example, maybe Tortured Tim is undergoing torture in order to prevent the torture or deaths of others, possibly loved ones or many other people. We wouldn't necessarily say the torture in itself is any less bad to him hedonically, and, among available alternatives, undergoing it may very well be best on his ethical views and best on many impartial views. Can we say that it's better for him? We might say so based on preference-based values, or by assigning substantial non-hedonic value to acting ethically or being virtuous.

On the other hand, if we allow such values, then our welfare range over a short interval of time may become unbounded (especially for someone with aggregative views like a utilitarian), which seems kind of suspect psychologically. Furthermore, if we're able to make interpersonal utility comparisons across such utility functions at all (but maybe we can't or shouldn't!), we may need to rely on psychologically plausible units, e.g. how psychologically motivating something is, which may keep such non-hedonic preferences from outweighing torture, since torture is extremely psychologically motivating, plausibly near the extreme of psychological motivation, at least while it's happening.

Or, Tim's non-hedonic preferences about his own torture relative to other things are just a separate component of his welfare, and we shouldn't normalize it by how bad torture is for him hedonically. Also, his preferences may just change over time, especially while being tortured compared to not being tortured.

Thanks for the post!

I am a little confused about the meaning of non-hedonic goods/bads. "Friendship, romantic love, acquiring knowledge, engaging in theoretical contemplation, doing meaningful work, developing practical skills, and so on" all refer to conscious/hedonic states. In which sense are those goods non-hedonic?

Thanks for the question, Vasco! So it's true that all those things could provide hedonic benefits. However, the idea is that all those things might not provide hedonic benefits--knowledge could be depressing, love could be taxing, etc.--and yet the objective list theorist would still say they add value to a life.

Thanks for the reply!

I would say that, even under a purely hedonistic view, it is always the case that knowledge, love etc. add value to life. They can add positive or negative value, depending on the specific snenario, but this uncertainty applies to any moral theory.

It appears to me that objective list theory values all and only hedonic states. However, while hedonist theories strive for improving these conscious states via focussing on heuristics more closely related to such states (e.g. life satisfaction), non-hedonist theories give more weight to other heuristics (e.g. objective list theory relies significantly on what is on the list as heuristics).

So I guess hedonism and objective list theory are different with respect to their methodology to increase value, but not on what they fundamentally value. Confusion might be generated when one says a given heuristic is intrinsically valuable:

Hi Vasco. I think you're using "hedonism" and "objective list theory" in different ways than I'm using them. I understand hedonism as the view that all and only positive experiences are good for you and all and only negative experiences are bad for you, independently of their sources. I understand objective list theory as the view that pleasures and pains are on the list of things that are good and bad for you, respectively, but there are lots of other things that are on those lists too--where those other things are good or bad for you independently of whether we enjoy them or dislike them.

Hi Bob,

Thanks for clarifying.

My interpretation is similar, but without the part "independently of their sources". I think it is not logically consistent to say that something is good or bad "independently of their sources", because all the sources influence conscious states. However, I believe one can say "without focussing primarily on the sources", which is what I meant to refer to with my heuristics discussion above.