In this post, I wish to outline an alternative picture to the grabby aliens model proposed by Hanson et al. (2021). The grabby aliens model assumes that “grabby aliens” expand far and wide in the universe, make clearly visible changes to their colonized volumes, and immediately prevent life from emerging in those volumes.

In contrast, the picture I explore here involves what we may call “quiet expansionist aliens”. This model also involves expansion far and wide, but unlike in the grabby aliens model, the expansionist aliens in this model do not make clearly visible changes to their colonized volumes, and they do not immediately prevent life from emerging in those volumes — although they do prevent emerging civilizations from developing to the point of rivaling the quiet expansionists’ technology and power.

The reason I explore this alternative picture is that I think it is a neglected possible model for hypothetical alien expansion. I am not claiming that it is the most plausible model a priori, but I think it is too plausible for it to be altogether dismissed, as it generally seems to be.

1. What changes in the quiet expansionist model?

The most obvious change in this model compared to the grabby aliens model is that we would not be able to see a colonized volume from afar, and perhaps not even from up close. Likewise, the quiet expansionist model implies that there would be more instances of evolved life, including observers like us, since the expansionist aliens would not immediately prevent such observers from emerging within their colonized volumes; they could instead stay around and observe. Taken together, this means that quiet expansionist aliens could in theory be here already, and they could even have a lot of experience interacting with civilizations at our stage of development.

Note that the grabby aliens model and the quiet expansionist model need not be mutually exclusive, as they could in principle be combined. That is, one could have a model in which there are both grabby (i.e. clearly visible) and quiet expansionist aliens that each rule their respective volumes, and different versions of the model could vary the relative proportion of these different colonization styles. (The original grabby aliens model only involves clearly visible expansionist aliens, not quiet expansionist ones; that is a helpful simplifying assumption, but it is worth being clear that it may be wrong.)

2. Arguments against the quiet expansionist model

A reason the quiet expansionist model is rarely taken seriously is that there seem to be some compelling arguments against it. Let us therefore try to explore a couple of these arguments, to see how compelling they are and what they should lead us to conclude.

2.1 “Implausible motive”

One argument is that it is implausible that an expansionist civilization would not visibly change its colonized volume. In particular, it is difficult to see what kind of underlying motive could make sense of such cosmic silence. The default expectation appears to be that we should instead see overt signs of colonization.

How convincing is this as an argument against the plausibility of quiet expansionist aliens? In order to evaluate that, it seems helpful to first outline what could, speculatively, be some motives behind quiet expansion. For example, it is conceivable that quiet expansion could aid internal coordination and alignment in a civilization that spans numerous star systems and perhaps even countless galaxies. By staying minimally concentrated and diversified across its colonization volume, a civilization might minimize risks of internal drift and conflict.

Another potential reason to stay silent is to try to learn about emerging civilizations (cf. the “info gain” hypothesis explored here). This might seem like a far-fetched reason to stay quiet, yet if the value of information gained from emerging civilizations is high, it might be a sufficient or at least supporting reason.

Furthermore, there is the dark forest hypothesis, or something in that ballpark, which roughly posits that aliens would stay quiet so as to avoid detection by, and resulting conflicts with, other civilizations. Note that such a motive would not require certainty about hostility from other civilizations — mere uncertainty about the motives of other potential civilizations might be enough to justify such a quiet approach. This is similar to the arguments that some have made against human attempts to send signals to alien civilizations based on the potential risks of sending such signals (see e.g. Todd & Miller, 2017).

Another motive for being quiet might be that sufficiently advanced civilizations would tend to realize that quiet expansion is a stable win-win equilibrium that avoids large-scale conflict with other advanced civilizations. In that case, they may naturally decide to adhere to a quiet strategy, lest they eventually get beaten by a larger coalition. A loose analogy to the contemporary human world might be how states generally do not invade international waters, in part because they know that a larger coalition would seek to undo such invasions. (To be clear, I am not claiming that being quiet is necessarily a win-win equilibrium for expansionist civilizations; I am merely claiming that this is yet another speculative possibility that warrants some level of consideration.)

Finally, there is a category of motives that we could call “unknown unknowns”, namely motives that we cannot readily conceive of, yet which might make sense to agents who are more advanced and better informed than we are. After all, it seems that we should not be confident that we can readily list all the plausible motives that a highly advanced intelligence might have.

Note that the motives outlined above are not mutually exclusive. That is, an expansionist civilization could potentially be quiet due to a combination of these motives — for example, to maintain internal coordination, to stay hidden from potential adversaries, and to study emerging civilizations.

In light of the potential motives outlined above, the “implausible motive” argument is hardly a decisive argument against quiet expansionist civilizations. There is a wide range of possible motives that might make sense of quiet expansion. Some of these motives appear at least somewhat plausible individually, and the broader category of such motives is more plausible still.

2.2 “Implausible convergence”

Another argument against a quiet expansionist model is that it would require an implausible degree of convergence, both within any single quiet expansionist civilization and across civilizations with different origins. After all, the argument goes, it would seemingly only require a single defiant faction to break the quiet policy and become a grabby civilization.

Would convergence toward being “quiet” within a single expansionist civilization be implausible? There are some reasons not to think so. For one, an advanced civilization could presumably be extremely capable, including when it comes to maintaining internal stability and alignment (cf. Finnveden et al., 2022).

Second, there might be strong strategic reasons to remain quiet that would be compelling to any rational sub-agent within the expansionist civilization (e.g. some of the specific motives outlined above, or an “unknown unknown” motive).

Third, it seems plausible that occasional defiants could be kept permanently in check if they are greatly outnumbered and overpowered by the pro-quiet faction, similar to how a few revolutionaries are unlikely to gain independence within a large nation-state. For example, if a small defiant faction tries to escape, they might be chased by a much larger faction that would prevent the defiant faction from accomplishing much.

What about convergence toward being “quiet” across civilizations? First, it is worth reiterating that, as a general matter, models with quiet expansionist civilizations do not require such convergence across civilizations. In particular, the above-mentioned combined models that involve both grabby and quiet expansionist civilizations obviously entail no such convergence. However, for the sake of argument, we can list some reasons why de facto convergence toward being “quiet” might be plausible even across civilizations.

Some of the reasons that could apply to convergence within civilizations might also apply to convergence across civilizations. For example, perhaps there are strong strategic reasons for being quiet that will be obvious to any advanced civilization. Or maybe there is a kind of cosmic selection pressure that pushes all civilizations toward being quiet.

Or perhaps quiet expansionist civilizations will tend to be so numerous that they are able to keep all budding grabby civilizations in check. In other words, scenarios with a sufficiently low ratio of grabby-to-quiet expansionist civilizations might eventually become de facto quiet everywhere. (The same might apply in reverse: for a sufficiently high ratio of grabby-to-quiet expansionist civilizations, the universe may converge toward an overall grabby equilibrium.)

Similarly, if we restrict our focus to (large) local regions of the universe, a state of purely quiet expansion could occur if the earliest expansionist civilization within a large radius happened to be a quiet one. By virtue of its earliness, such a civilization could impose its quiet rule on a vast cosmic volume — potentially spanning a billion light years or more — even if not all civilizations converge toward being quiet on the largest scale.

In light of these considerations, the “implausible convergence” argument is hardly that convincing either. In particular, it does not seem to be a decisive argument against models that involve quiet expansionist civilizations, including models that involve de facto convergence toward quiet expansion, whether in a large local vicinity or (less probably) across the entire universe.

Lastly, in our efforts to think clearly about these matters, it is worth being aware of our tendency toward belief digitization: our tendency to round the probability of less likely possibilities down to zero (see also Gettys et al., 1973; Fernbach et al., 2010). Thus, even if scenarios involving quiet expansionist civilizations do not seem to be the most likely ones — even if they only deserve, say, a 10 percent prior probability conditional on alien expansion — this should not lead us to altogether disregard this class of scenarios.

3. Arguments in favor of the quiet expansionist model?

Having explored two key arguments against the quiet expansionist model, it is worth asking whether there are any arguments that positively favor this model. It seems to me that there are. In particular, it seems that certain anthropic considerations — i.e. considerations relating to observation selection effects — support quiet expansionist models, at least relative to the “standard” grabby model.

For example, if we assume a mixed model that involves both grabby and quiet expansionist civilizations, there would be more observers like us (e.g. observers living in civilizations at our current stage of development) in scenarios with a higher proportion of quiet expansionist vs. grabby civilizations. By extension, there would be far more observers like us in a pure quiet expansionist versus a pure grabby model.

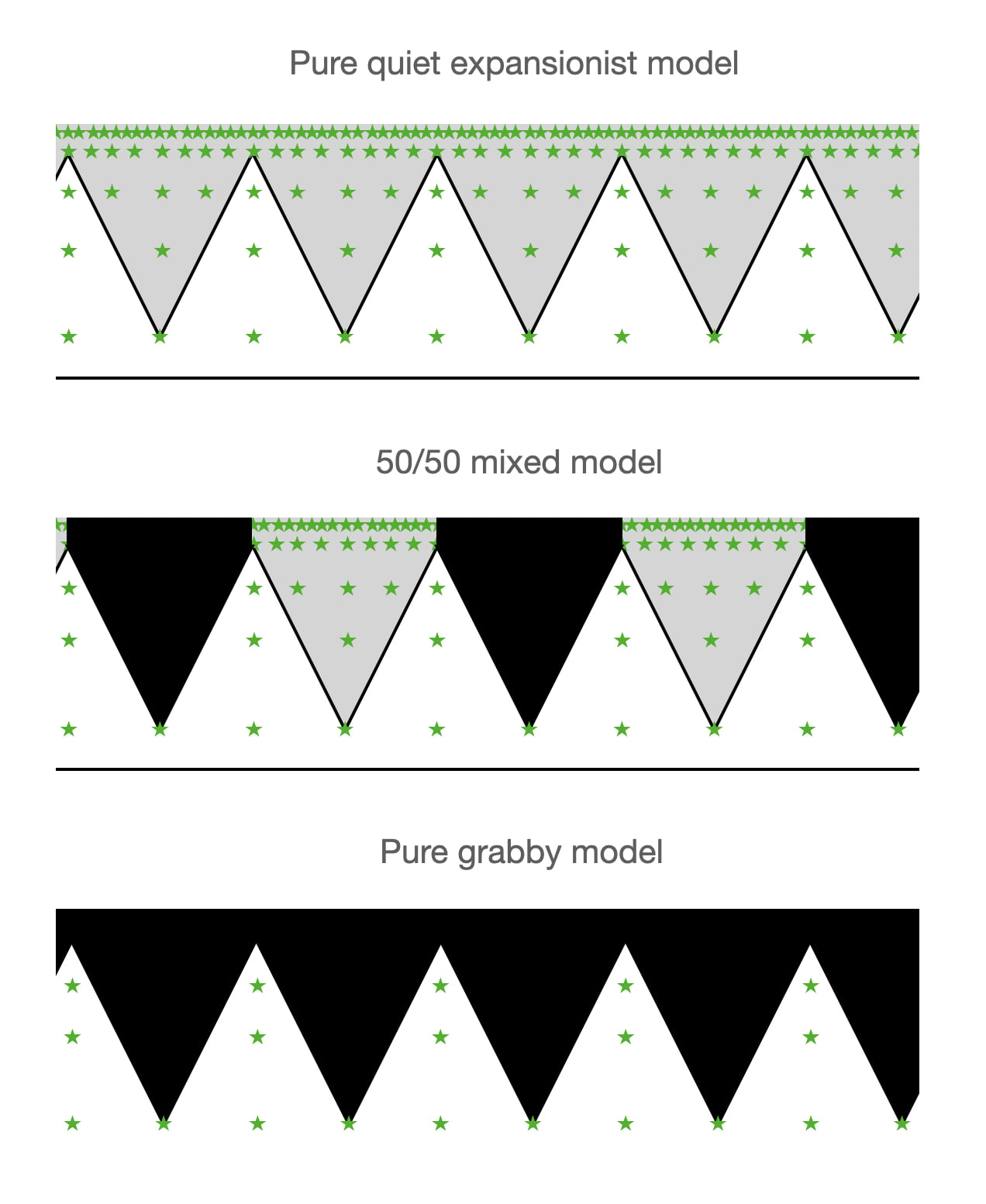

This is illustrated in the three toy figures below, in which the green stars represent civilizations at roughly our stage of development. In each of the figures, time increases along the vertical axis while space extends along the horizontal axis; the grey areas represent quiet expansionist colonizations while the black areas represent grabby colonizations. The green stars become increasingly prevalent over time because we here assume the hard-steps model described by Hanson et al. (2021, pp. 3-4).

As we can see, the further we get toward a pure quiet expansionist scenario, the more observers there are like us.

Similarly, in terms of where we should expect to find ourselves within a specific scenario that contains both grabby and quiet expansionist civilizations, there would generally be more observers like us in the parts of the universe that are ruled by quiet expansionist civilizations.

We can phrase these points in terms of the two canonical assumptions in anthropic reasoning, namely the Self-Indication Assumption (SIA: updating based on observer prevalence across different hypothetical scenarios) and the Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA: updating based on observer prevalence within a fixed scenario). That is, SIA generally pushes us toward believing in a higher ratio of quiet expansionist to grabby civilizations, while SSA generally pushes us toward thinking that we find ourselves inside a quiet expansionist volume (at least this latter claim would hold true in a wide range of mixed scenarios that are not close to being purely grabby).

3.1 Qualifications to this argument

Some key qualifications are worth stressing about the anthropic argument outlined above. First, it is notoriously difficult to know what to make of anthropic arguments, which suggests that we should be cautious in drawing strong inferences from such arguments. Thus, to be clear, I present this argument as one that is worth pondering, not as a definitive argument from which we should draw any strong conclusions.

Second, the argument presented above is by no means exhaustive in terms of the possibilities it explores. The argument only compares two simple models, or rather a continuum of simple models between the two extremes of fully grabby and fully quiet expansionist models. Yet there are, of course, many other options than these. For example, another model might say that large-scale space colonization is simply impossible (such a model would have its own strengths and weaknesses).

We should thus be clear that the anthropic argument outlined above only favors (simple) quiet expansionist models in comparison to (simple) grabby models (e.g. it favors models with a higher prevalence of quiet expansionist relative to grabby civilizations). It does not necessarily say much about the plausibility of the quiet expansionist model compared to other competing colonization models, or about the plausibility of this quiet expansionist model in absolute terms.

These qualifications notwithstanding, the argument does seem to pose a challenge to the simple grabby aliens model as proposed by Hanson et al.

4. Objection: Fails to explain earliness

An objection to the anthropic argument outlined above is that the quiet expansionist model fails to explain our apparent earliness in cosmic history. For example, Hanson et al. argue that humanity has appeared surprisingly early in cosmic history, and they propose their grabby aliens model as a way to explain that earliness, since grabby aliens would prevent new civilizations from emerging (Hanson et al., 2021, sec. 2). But in the quiet expansionist model, it is not clear how this earliness is explained.

I see at least two reasons why this objection should not lead us to dismiss quiet expansionist models. First, it is unclear whether there indeed is an earliness problem. On some assumptions about what kinds of star systems can give rise to life, our appearance date may in fact be quite typical, and thus not particularly early (see e.g. Burnetti, 2016; 2017). If these assumptions are correct, there is no earliness problem. And since it is highly uncertain which stars can give rise to life, it seems that we should place a substantial probability on there being no earliness problem to begin with.

Second, quiet expansionist civilizations could, like grabby ones, imply a deadline on the emergence of new civilizations at some point, even if they would not do so initially. Such a deadline need not be mysterious, and it could even be a clear strategic necessity, at least within some plausible versions of the quiet expansionist model. For example, we can imagine a version of the model in which the quiet expansionists prevent any further life from emerging once they encounter other expansionist civilizations that originated elsewhere, or when they encounter hostile expansionists in particular. In that case, some of the motives for being quiet and not using all resources available to them might no longer apply (e.g. the motive of trying to remain hidden from potential cosmic adversaries).

In sum, the purported earliness problem does not seem to be a valid reason to dismiss quiet expansionist models, nor is it a valid reason to dismiss the anthropic argument that supports such models relative to the pure grabby aliens model.

5. Conclusion

The quiet expansionist model is a conjecture that could simultaneously:

- Answer the Fermi question: according to this model, they are most likely out there, and probably even here (cf. the illustration above).

- Account for (much of) the great filter that prevents visible colonization of the cosmos: quiet expansionist civilizations would generally impose a future filter on civilizations like ours.

- Be favored by anthropic considerations and make us typical observers (of our kind), in line with the Copernican Principle.

- Help explain the hardest (seemingly) anomalous UFOs: they might be silent cosmic rulers.

To be clear, my claim here is not that the quiet expansionist model is in fact true. But as a conjecture, I submit that it deserves more consideration than it has received so far.

Appendix: SIA also favors quiet expansionist models over Rare Earth models

[This appendix was added Nov., 2024.]

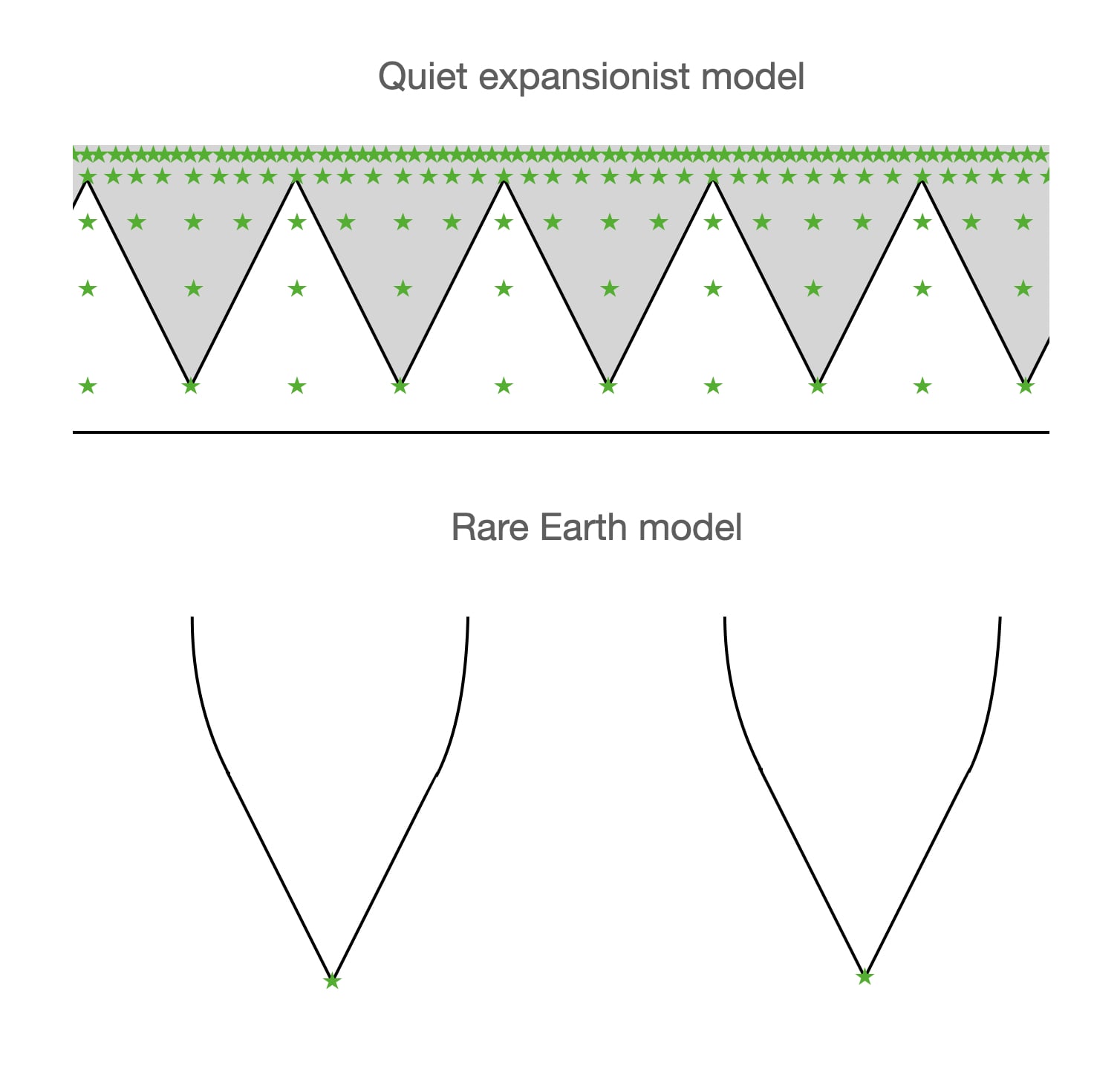

An alternative model to the ones outlined above is a Rare Earth model according to which advanced civilizations emerge so rarely and so far apart that they can never reach each other (due to cosmic expansion). This seems to be a fairly common view of the prevalence of advanced civilizations.

While it may be a trivial point, it is worth noting that SIA also favors the quiet expansionist model over this kind of Rare Earth model — plausibly by orders of magnitude — as illustrated in the toy figure below.

Again, I am not claiming that SIA is the correct or most appropriate way to reason about anthropics. The point here is just that if we apply SIA, the quiet expansionist model seems strongly favored over the Rare Earth model. Additionally, if we are willing to update toward visible or grabby aliens being prevalent based on SIA (cf. Finnveden, 2019), we should arguably also update toward the quiet expansionist model. Indeed, the SIA update toward the quiet expansionist model is far stronger than the corresponding update toward the grabby model (cf. the first illustration above).

At any rate, even if we only assign limited weight to SIA, it might still count as a notable consideration against placing a very low prior on us being in a quiet expansionist scenario. It might even be a reason to assign a higher prior to quiet expansionist models than to Rare Earth and grabby models combined.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Tristan Cook for helpful comments.

Interesting! Fwiw, the best argument I can immediately think of against silent cosmic rulers being likely/plausible is that we should expect these to expand slower than typical grabby aliens and therefore be less "fit" and selected against (see my Grabby Values Selection Thesis -- although it seems to be more about expansion strategies than about values here).

Not sure how strong this argument is though. The selection effect might be relatively small (e.g. because being quiet is cheap or because non-quiet aliens get blown up by the quiet ones that were "hiding"?).

Thanks for your comment, Jim. :)

Why would you expect grabby aliens to expand faster than quiet expansionist ones? I didn't readily find a reason in your linked piece, and I don't see why loud vs. quiet per se should influence expansion speeds; both could presumably approach the ultimate limit of what is physically possible?

Just speculating here, but if you want to capture most of the energy of a star (e.g. by a Dyson swarm), this will be visible. And if you can only use a fraction of the energy available, this might reduce your expansion speeds.

Yeah so I was implicitly assuming that even the fastest civilizations don't "easily" reach the absolute maximum physically possible speed such that what determines their speed is the ratio resources spent on spreading as fast as possible [1] : resources spent on other things (e.g., being careful and quiet).

I don't remember thinking about whether this assumption is warranted however. If we expect all civs to reach this maximum physically possible speed without needing to dedicate 100% of their resources to this, this drastically dampens the grabby selection effect I mentioned above.

[1] which if maximized would make the civilization loud by default in absence of resources spent on avoiding this I assume. (harfe in this thread gives a good specific instance backing up this assumption)

I see, thanks for clarifying.

In terms of potential tradeoffs between expansion speeds vs. spending resources on other things, it seems to me that one could argue in both directions regarding what the tradeoffs would ultimately favor. For example, spending resources on the creation of Dyson swarms/other clearly visible activity could presumably also divert resources away from maximally fast expansion. (There is also the complication of transmitting the resulting energy/resources to frontier scouts, who might be difficult to catch up with if they are at ~max speeds.)

By rough analogy, if a human army were to colonize a vast (initially) uninhabited territory at max speed, it seems plausible that the best way to do so is by having frontier scouts rush out there in a nimble fashion, not by devoting a lot of resources toward the creation of massive structures right away. (And if we consider factors beyond speed, perhaps not being clearly visible also has strategic advantages if we add uncertainty about whether the territory really is uninhabited — an uncertainty that would presumably be present to some extent in all realistic scenarios.)

Of course, one could likewise make analogies that point in the opposite direction, but my point is simply that it seems unclear, at least to me, whether these kinds of tradeoff considerations would overall favor "loud civ expansion speed > quiet civ expansion speed" (assuming that there are meaningful tradeoffs).

Besides, FWIW, it seems quite plausible to me that advanced civs would be able to expand at the maximum possible speed regardless of whether they opted to be loud or quiet (e.g. they might not be driven by star power, or their technology might otherwise be so advanced that these contrasting choices do not constrain them either way).

This is a pretty interesting idea. I wonder if what we perceive as clumps of 'dark matter' might be or contain silent civilizations shrouded from interference.

Maybe there is some kind of defense dominant technology or strategy that we don't yet comprehend.

The dark matter thought has crossed my mind too (and others have also speculated along those lines). Yet the fact that dark matter appears to have been present in the very early universe speaks strongly against it — at least when it comes to the stronger "be" conjecture, less so the weaker "contain" conjecture, which seems more plausible.

Executive summary: The "quiet expansionist aliens" model proposes that advanced alien civilizations may expand across the universe without making visible changes, allowing life to emerge but preventing rival civilizations, which could explain the Fermi paradox and UFO sightings.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Refuting 3: Life/history simulations under visible/grabby civs would far outnumber natural origin civs under quiet regimes.

If one includes sims, grabby civs would possibly but not necessarily have more observers (like us) than quiet expansionist civs. For example, the expected number of sims may be roughly the same, or even larger, in quiet expansionist scenarios that involve a deadline/shift (cf. sec. 4).[1] There's also the possibility that computation could be more efficient in quiet regimes (some have argued along these lines, though I'm by no means saying it's correct; I'm not sure if we currently understand physics well enough to make confident pronouncements either way).

But yes, the argument outlined in Section 3 was limited to "base reality" scenarios. Conditional on you not being in a simulation (e.g. if exact sims of your conscious experience are not possible), the anthropic argument in Section 3 suggests that you're in a quiet expansionist scenario, or in a quiet expansionist region within a mixed scenario. Conditional on you being in a simulation, it seems unclear.

Why might it be even larger? Intuitively, one might think that grabby civs could start simulating earlier, since they don't have to wait and be quiet. But in the quiet expansionist model, expansionist civ origin dates would, in expectation, be significantly earlier, since we could be past the point where they've fully colonized. That is, in a grabby model, we'd now be pre-deadline and pre-colonized, whereas we may be "post-colonized" in the quiet expansionist model — indeed, we most likely would be if the hard-steps model is correct. So the expansionist civs would be considerably older (they could even be much older) in the quiet expansionist vs. the grabby model. Thus, if we only look at the past, it's conceivable that quiet civs would be able to run more sims, even if they have considerably fewer sims per colonized volume (as they might make up for it by having far more time and volume).

At any rate, given the apparent size of the cosmic future compared to the past, what matters most for the expected number of sims is hardly earliness (e.g. full cosmic expansion at 9 vs. 15 billion years), but arguably more something like future willingness and capacity to devote resources toward simulations. And when it comes to the willingness aspect, I can see some reasons to think that civs that started out as quiet expansionists up till our point (not necessarily staying that way) might have more incentive to simulate vs. grabby ones. For example, the strategic situation and motives in quiet expansionist scenarios would plausibly be more concerned with potential adversaries from elsewhere, and civs in such scenarios may thus be significantly more inclined to simulate the developmental trajectories of potential adversaries from elsewhere, or civs that could give information about such adversaries. Of course, this is speculative, but it serves to show that the picture with sims is complicated and the upshots are non-obvious.

The aestivation hypothesis was refuted by gwern as soon as it was posted and then again by charles bennet and robin hanson. Afaik, the argument was simple: being able to do stuff later doesn't create a disincentive from doing visible stuff now. Cold computing isn't relevant to the firmi hypothesis.

Huh, so I guess this could be one of the very rare situations where I think it's important to acknowledge the simulation argument, because assuming it's false could force you to reach implausible conclusions about techno-eschatology. Though I can't see a practical need to be right about techno-eschatology, that kind of thing is an intrinsic preference.

I haven't been able to think of a lot of reasons a civ would simulate nature beyond intrinsic curiosity. That's a good one (another one I periodically consider and then cringe from has to do with trade deals with misaligned singletons). Intrinsic curiosity would be a pretty dominant reason to do nature/history sims among life-descended species though.

I think the average quiet regime is more likely to just not ever do large scale industry. If you have an organization whose mission was to maintain a low activity condition for a million years, there are organizational tendencies to invent reasons to continue maintaining those conditions (though maybe those don't matter as much in high tech conditions where cultural drift can be prevented?), or it's likely that they were maintaining those conditions because the conditions were just always the goal. For instance, if they had constitutionalised conservationism as a core value, holding even the dead dust of mars sacred.

On "cold computing": to clarify, the piece I linked to was not about aestivation / waiting. It was about using "cold computing" right away.

The comment from gwern lists some reasons that may speak against "cold computing" (in general) as playing a significant role in answering the Fermi question, but again, a question is how decisive those reasons are. Even if such reasons should lead us to think that "cold computing" plays no significant role with 95 percent confidence, it still seems worth avoiding the mistake of belief digitization: simply collapsing the complementary 5 percent down to 0.

In any case, the point about "cold computing" was merely a disjunctive possibility; the broader point about observer prevalence being unclear in 'grabby vs. quiet expansionist scenarios that include sims' does not rest on that particular possibility.

On simulations: I think it can make sense to set the simulation argument aside, at least provisionally, for a couple of reasons:

I see. I glossed it as the variant I considered to be more relevant to the firmi question, but on reflection I'm not totally sure the aestivation hypothesis is all that relevant to the firmi question either... (I expect that there is visible activity a civ could do prior to the cooling of the universe to either prepare for it or accelerate it).

I think that your model is correct and 'anthropically' supported.

In some sense it favors 'zoo hypothesis". However, there is an important distinction: is it zoo or natural reserve. In general, on Earth zoos are rare but well kept and natural reserves are more abundant, but less controlled. The same anthropic considerations which favor silent rulers, favor natural reserves vs zoos.

This has bad consequences for us: natural reserves are more likely to be visited by unauthorized visitors and poachers. Or if we will be less anthrophomorphisng, they have less value for cosmic rulers as they are more numerous. UFOs observations and their alleged connections with cattle mutilations and abductions are more favoring the idea that Earth is less protected hunting ground than well protected zoo.

Speaking about "unobservable" part. Aliens which consist of fields or using something like "5-th" dimension to travel will have much less visible footprint but will have much large sphere which they can grab, as they can travel with almost light speed. The same anthropic considerations favor such aliens as they will have larger sphere of influence. Observations of UFOs also imply that they use some non-typical for us way of propulsion, like instant acceleration, manipulating gravity and moving through objects.

In other words, if aliens are not interesting in building Dyson spheres and can travel with near-light speed without leaving visible traces, we will see much less signs of their activity. Maybe they are more interested in controlling space than in performing a lot of computations.

The conclusion is unpleasant: we are typical and neglected planet which sometimes is abused by our mostly invisible rulers. But it is the same as life situation of most people on Earth.

Thanks for your comment. :) One reason I didn't use the term "zoo hypothesis" is that I've seen it defined in rather different ways. Relatedly, I'm unsure what you mean by zoo vs. natural reserve hypotheses/scenarios. How are these different, as you use these terms? Another question is whether proportions of zoos vs. natural reserves on Earth can necessarily tell us much about "zoos" vs. "natural reserves" in a cosmic context.

Maybe better say 'zoo' vs 'forest', or 'very well protected area' vs 'partly protected area'.

If there is only a few habited planets inside grabby alien sphere, they will be very valuable and very well protected so no UFOs will be observed.

If there are millions of them, they are less valuable and thus less protected and therefore can be used for some practical activity, like turism, hunting or mining unobtanium. Obviously, if UFOs are aliens, local alien authorities let them be visible sometimes, so local aliens laws are not very strict.

Observation selection effects like SIA favors the hypothesis that there millions habitable planets inside any grabby aliens.