This post is the first in a series I plan to write about management from an EA perspective, mostly oriented towards hiring. Feedback on which topics are useful to cover would be appreciated!

TL;DR: Are you the best in the world at a specific task, such as optimising your company's database? This still might not be the highest impact thing for you to do!

I sometimes talk to prospective employees of CEA who say something like:

- I am the best in the world at optimising my company's obscure proprietary database

- EA organisations don't need anyone to optimise this obscure proprietary database

- Therefore, I should use my “comparative advantage” and work at my current employer optimising their obscure proprietary database, and other people who have a comparative advantage at working at CEA should work there

Comparative advantage is a useful concept, but it doesn’t mean "everyone does the thing which they are best at in the world." If this were true, there would be only one chef in the world (the person who is best at being a chef), only one baker, one software engineer, etc.

What this approach misses is that sometimes the world needs a 40th percentile graphic designer at an EA organisation more than a 99.999th percentile obscure-proprietary-database-optimizer at some other organisation.

I am grateful to the candidates who apply to CEA and say something like “I want you to hire the best person for this position, and am totally happy if you would rather I continue to optimise my company’s obscure proprietary database instead of working for you.” But the important thing is that these candidates apply to the position – unless you are the hiring manager for a position, you probably don’t know what the labor pool is like, and therefore can’t really use the theory of comparative advantage in a useful way.

Appendix – technical argument

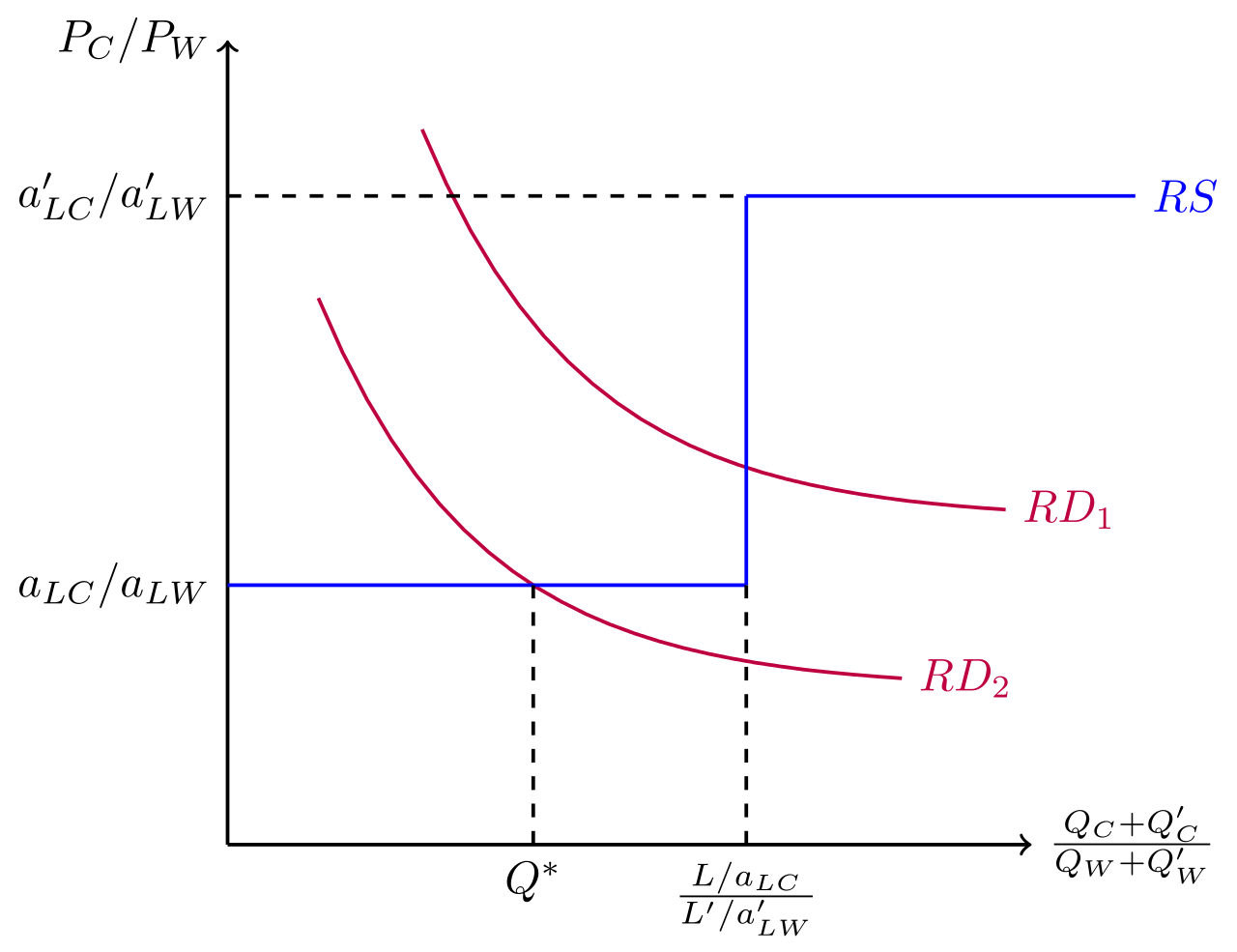

The above is an informal argument. Using more technical terms: the mistake people are making is that they are looking only at labor supply, and not labor demand:

From Wikipedia

If you ignore demand, then you could indeed end up with a scenario where everyone supplies just what they are best able to supply.[1] But that’s not what the theory of comparative advantage actually tells you to do: you also need to know about demand.[2]

You are sometimes able to actually draw these curves: for example if you and a friend are both considering the same two jobs, and the two of you are the only candidates, and both jobs can only hire one of you. In this scenario, you and your friend should consider your comparative advantages.

But this scenario is pretty rare, and in general I have found that the theory of comparative advantage leads people astray more frequently than it is helpful.

80,000 Hours has an article which discusses this in more depth. Lizka wrote a short story about Superman with a similar moral. I would like to thank Will Fenning, Caitlin Elizondo, Max Dalton, Yonatan Cale, Lizka Vaintrob, Jonathan Michel and JP Addison for comments on earlier drafts.

Interesting stuff! It's definitely got me thinking about my own comparative advantage as well, especially since EA doesn't have a typical distribution of talents. I'm a software engineer, and we're vastly overrepresented in EA relative to the general population.

You make a great point about how organisations know the labor pool, and individuals don't, and that info is needed to understand comparative advantage well. I suppose that would mean the right advice for individuals is " Pay attention to the signals coming from the market." For instance, I consider myself a better software engineer than a writer, but thus far when I apply for EA engineering jobs I haven't had a ton of luck, and when I enter EA writing contests I win small prizes. So I wonder if this is a case where my comparative advantage might lie outside of engineering just because we already have a lot of strong engineering talent in a way that isn't as true with writing.

Although perhaps even better would be to utilise the Pareto frontier where I have skills at both - e.g, skilling up in ML and then working to become a distiller of AI safety research, which requires both technical skill AND ability to write well.

It's a difficult question! But the lesson I have definitely taken from this article is "Apply for things, pay attention to what happens."

Besides distillation, another option to look into could be the Communications Specialist or Senior Communications Specialist contractor roles at the Fund for Alignment Research.

That's an interesting example! It does seem like you having success with writing contests is meaningful evidence; the distillation thing does potentially seem promising.

Overall this is a good point, but I have one nit:

I don't think this follows; in particular, following the policy "everyone does the thing which they are best at in the world" doesn't actually make a prescription for most people, since most people are not the best in the world at anything (unless you take a weirdly granular view of things, like "the best Orthodontist named P. Sherman, with an office at 42 Wallaby Way, Sydney", at which point the reductio stops seeming obviously absurdum)

I agree with your post overall, but:

This is nonsensical for a different reason. There are billions of humans, but only ~thousands (hundreds?) of jobs at the granularity of "chef", "baker", "software engineer". Not everyone will be the best in the world at one of these jobs.

This would seem more correct if it was "there would be only one person making croissants filled with grape jelly, only one person planting Fuji apple seeds, only one person installing Proprietary-Medical-Device, etc".

Yes, bwr makes a similar point here.

Oh huh, I somehow missed that on my first read.

Thanks for the article! I was a little confused by the title "doing the thing you're best at" on whether it means "doing the thing you're best at compared to everything else you know how to do" or "doing the thing you're best at compared to everyone else", where the former is comparative advantage and the latter is absolute advantage? The content of your article is clearer though - thanks for that.

Greg Mankiw’s introductory econ textbook has a good explanation of a similar point:

LeBron James is a great athlete. One of the best basketball players of all time, he can jump higher and shoot better than most other people. Most likely, he is talented at other physical activities as well. For example, let’s imagine that LeBron can mow his lawn faster than anyone else. But just because he can mow his lawn fast, does this mean he should?

Let’s say that LeBron can mow his lawn in 2 hours. In those same 2 hours, he could film a television commercial and earn $30,000. By contrast, Kaitlyn, the girl next door, can mow LeBron’s lawn in 4 hours. In those same 4 hours, Kaitlyn could work at McDonald’s and earn $50.

In this example, LeBron has an absolute advantage in mowing lawns because he can do the work with a lower input of time. Yet because LeBron’s opportunity cost of mowing the lawn is $30,000 and Kaitlyn’s opportunity cost is only $50, Kaitlyn has a comparative advantage in mowing lawns.

(From Mankiw, G., Principles of Economics, p. 54, 9th edition)

Suppose we modify this example, such that:

Even though LeBron is better at mowing lawns than at television commercials, and also ranks higher among those who mow lawns than among those who film television commercials, he should film the commercial.