This essay was written for the Worldview Investigations category of Open Philanthropy’s Cause Exploration Prizes by staff at the Happier Lives Institute

Summary

Open Philanthropy recognises the need to measure benefits beyond health and income. We think that subjective wellbeing is the best tool for the task. Subjective wellbeing (SWB) is measured by asking people to rate how they think or feel about their lives. We propose the wellbeing-adjusted life year (WELLBY), the SWB equivalent of the DALY or QALY, as the obvious framework to do cost-effectiveness analyses of non-health, non-pecuniary benefits. As our previous work has shown that using WELLBYs can change funding priorities by giving more weight to improving mental health, compared to DALYs or income measures; and they may reveal different priorities in other areas too.

The advantages of SWB over alternatives are fourfold. (1) SWB captures and integrates the overall benefit to the individual from all of the instrumental goods provided by an intervention. This avoids the challenging problem of assigning moral weights to different goods, makes spillover effects easier to estimate, and clarifies the importance of philosophy. (2) SWB is based on self-reports by the affected individuals whereas Q/DALYs rely on flawed predictions about how good or bad we think a malady will be for ourselves or others. (3) Using SWB will reveal previously under-captured benefits, such as it has already been done for psychotherapy. (4) Measures of subjective wellbeing already exist, are easy to collect, and are widely (and increasingly) used in academia and policymaking across an extensive array of circumstances and populations of interest. Furthermore, subjective wellbeing measures are reliable and valid instruments, and the existing evidence supports consistent use across people.

Having said that, SWB is not without its disadvantages. (1) There is little research on the comparability between SWB scales across people. (2) We don’t know where the ‘neutral point’ lies on SWB scales. (3) We’re unsure how to choose the best measure of SWB (e.g., life satisfaction or happiness) or how to convert between them. (4) There are very few cost-effectiveness analyses using WELLBYs. Fortunately, we think these issues can be resolved, and we are actively working towards doing so.

1. The problem and a solution

Open Philanthropy’s mission is to help others as much as possible. Its human-focused Global Health and Wellbeing grantmaking aims to save lives, improve health, and increase incomes. However, Open Philanthropy recognises that measuring changes to health or income does not capture all the benefits experienced by the recipients. So, they ask, how should they account for the effects of injustice, discrimination, empowerment, and freedom? To that list, we could also add crime, loneliness, and corruption. Whilst the standardised health metrics, QALYs and DALYs, make it easier to compare different health states in the same units, the broader challenge is to find a common currency that allows sensible trade-offs between health, wealth, and non-health, non-wealth outcomes. How could this be done?

We take it that Open Philanthropy is interested in funding interventions that improve wellbeing. Therefore, reducing discrimination (or injustice, etc.) is good mostly because it increases wellbeing, any other reason is secondary.[1] But what is ‘wellbeing’? Philosophers have three main theories: (1) positive experiences, (2) satisfied desires, and (3) a multi-item ‘objective list’ that includes ‘objective’ goods such as knowledge, achievement, and love. Conspicuously absent from this list are wealth and health. Most people conclude that, on reflection, these are not intrinsically valuable for us (i.e., they are not valuable in themselves). Rather, they are instrumentally valuable, a means to achieve some further end. We don’t seek money purely for its own sake, but because we think it will make us happier, satisfied, or realise one of the objective goods that plausibly constitutes wellbeing.

What does this mean for Open Philanthropy? Straightforwardly, it suggests we should measure wellbeing directly, if that’s possible, rather than any item, or combination of items, that we assume contribute to wellbeing. Can this be done? We think the answer is yes and, indeed, has been lying under our noses for some time, waiting to be put to work.

It is already common practice to combine changes to the quality and quantity of health using QALYs and DALYs. The limitations of these measures are well-established (see Foster, 2020) and there has been a long-standing call for something better and broader than Q/DALYs. What we really want are WELLBYs, wellbeing-adjusted life-years.

WELLBYs are constructed by measuring people’s subjective wellbeing, how they rate the quality of their own lives. One commonly used question, which has been asked in thousands of surveys (Veenhoven, 2020), is life satisfaction: “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life, nowadays?”. People are already familiar with the idea of rating our satisfaction in many domains (the jobs we do, the goods we buy, the services we receive, etc.). We find rating our lives as a whole a small and easy shift[2].

Once we’ve selected a subjective wellbeing measure we have to specify how we construct WELLBYs from it. A straightforward way is to define a WELLBY as a one-point increase in life satisfaction (on a 0 to 10 scale), for one person, for one year. So, if Alice goes from 3/10 to 5/10 for half a year, or from 3/10 to 4/10 for one year, that is worth 1 WELLBY. If Bob is at 7/10, extending their life for one year is worth 7 WELLBYs. We are skirting over some controversial issues here and will return to these in Section 5.

How would the WELLBY capture the impact of health, wealth, discrimination, freedom and the like? Quite straightforwardly, in fact. We can determine, using standard social science research methods, how much each factor impacts subjective wellbeing. So, if a doubling of income and a certain increase in freedom had the same effect on life satisfaction (0.5 WELLBYs for example), we would say they were equally valuable.

Given this, we think the WELLBY is an obvious option, not just for Open Philanthropy, but for anyone else that wants a principled method to compare how different kinds of intervention benefit people and by how much. We do not claim the WELLBY is perfect – it is not – but it does represent a decision-relevant improvement over Q/DALYs and a better alternative to relying on intuitive judgements about the quality of other people’s lives.

In the rest of this document, we lay out the details of using WELLBYs and SWB. We ask and address the following questions in the rest of this document: How is subjective wellbeing (SWB) measured (Section 2)? How widely has SWB been used (Section 3)? What are the advantages of using SWB compared to the alternatives (Section 4)? And what are the challenges of using SWB and what further work is needed to resolve them (Section 5)?

2. How to measure subjective wellbeing

Subjective wellbeing (SWB) is how people rate their feelings or judgements about their lives (i.e., how happy or satisfied they are). SWB is defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2013) as “good mental states, including all of the various evaluations, positive and negative, that people make of their lives and the affective reactions of people to their experiences”. SWB is commonly measured by responses on a 0 to 10 scale to questions like “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?” or “Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?” (ONS, 2019).

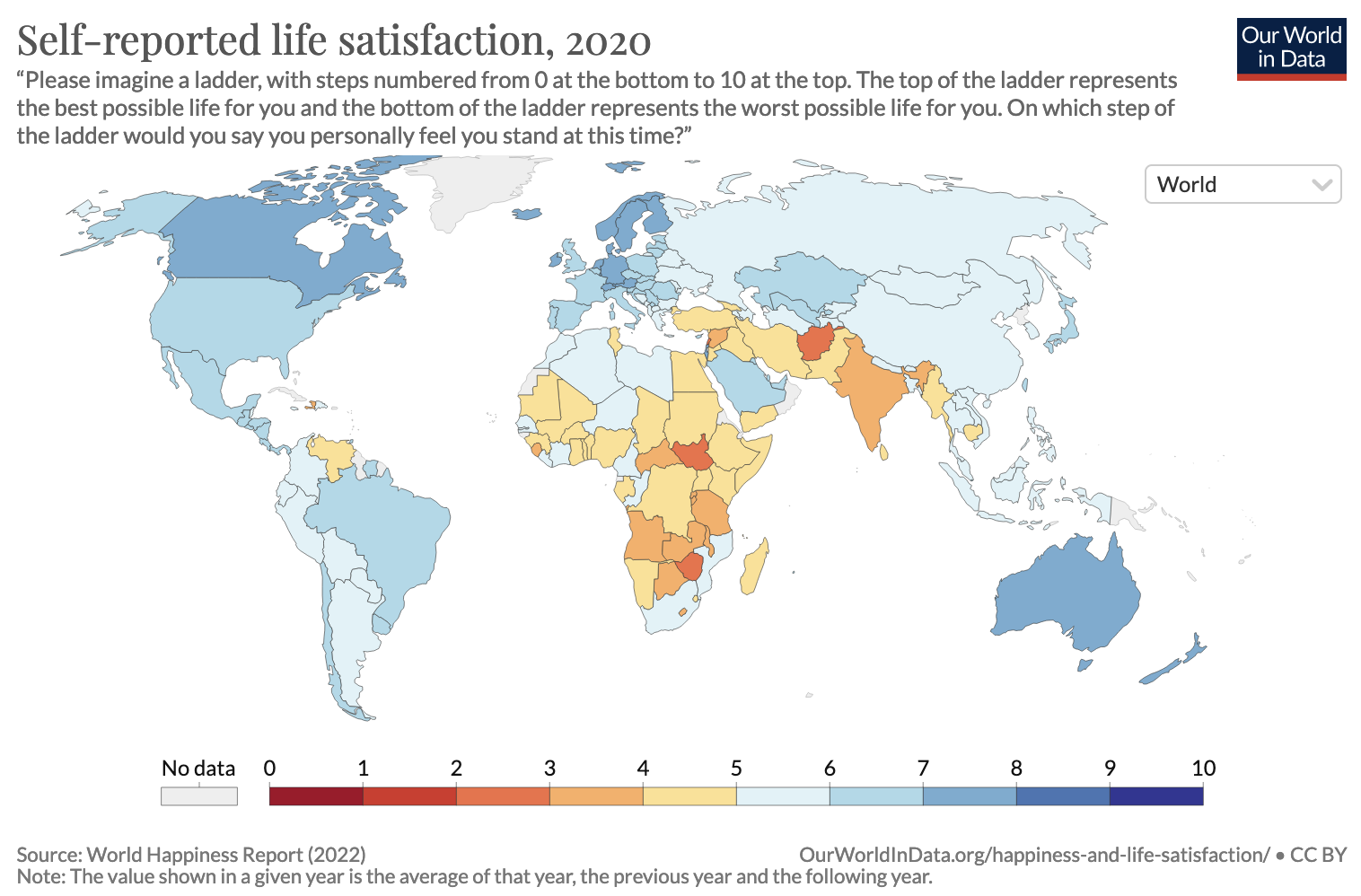

Extensive research has shown that common SWB measures are valid. Namely, SWB measures accurately reflect the SWB states that we are trying to measure. To be valid, a measure must be reliable; it gives the same output for the same input. Reviews such as the one by the OECD (2013) or Tov et al. (2021) find that common measures of SWB are reliable under these conditions. Beyond reliability, a measure is valid if it captures the underlying phenomenon it set out to capture (i.e., it is correlated with what we think it should be). SWB is, indeed, correlated with the good things in life and negatively correlated with the bad things in life (Kahneman & Krueger, 2006). Relationships, income, and time in nature are positively associated with SWB whilst unemployment, bereavement, commuting, crime, and health problems are negatively associated with SWB (Clark et al., 2018; Dolan et al., 2008). In Figure 1 (based on Gallup World Poll data), we can see that countries afflicted by poverty, lower development, crises, and conflict have lower average life satisfaction compared to richer and more stable nations.

Figure 1. Average life satisfaction across the world in 2020 (Our World in Data)

3. Current uses of subjective wellbeing

Subjective wellbeing (SWB) is an accepted method, with official policies, in several countries[3]. For example, the UK government has guidelines on SWB's measurement (Dolan et al., 2011) and use in cost-effectiveness analyses (HM Treasury, 2021). The Gallup World Poll has surveyed people about their life satisfaction in most countries every year since 2003, the results of which are reported as a cornerstone of the UN’s annual World Happiness Report.

The academic field of wellbeing science has grown at a rate of 5.5% per year over the last decades (Barrington-Leigh, 2022), swelling to probe a panoply of topics. See Figure 2, below, taken from Layard (2020). Deiner et al. (2018), coming from a psychology perspective, overviews SWB’s relationship to temperament, relationships, performance, creativity and culture. Clark (2018) reviews the past four decades of happiness economics, covering SWB’s relationship to employment, occupation choice, inequality, inflation, and using SWB to value greenery, pollution or noise. Our World in Data (2017) presents many of the literature's key findings about income, health, culture, and measurement issues.

Figure 2. Number of subjective wellbeing papers over time (from Layard, 2020)

Beyond these typical topics for SWB, it’s also been used to estimate the impact of many other events and conditions such as the effect of immigration on movers, natives, and home communities (Hendriks et al., 2018), the quality of governance (Helliwell et al., 2018), corruption (Li & An, 2020), and conflict (Bosnia-Herzegovina: Shemyakina & Plagnol, 2013; Ukraine: Coupe & Obrizan, 2016; Syria: Cheung et al., 2020).

There is also a literature on the relationship between SWB and hard-to-measure concepts such as discrimination, injustice, freedom and empowerment. For instance, perceived discrimination is strongly related to SWB (r = 0.24, based on 328 independent estimates and 144,246 participants, Schmitt et al., 2014). Affective mental health - which we consider to be a proxy for SWB[4] - has been used to measure the causal impact of police killings in the USA (Bor et al., 2018), which are widely considered a consequence of injustice. Differences in freedom across countries better explain differences in SWB than differences in income (Helliwell et al., 2020), increases in freedom relate to increases in SWB across countries (Inglehart et al., 2008), and decreases in civil liberties decrease life satisfaction (Windsteiger et al., 2022). Finally, Fielding and Lepine (2017) finds that a sense of empowerment has a larger effect on SWB than income.

Wellbeing science is now an established field and we are not the first to propose WELLBYs. We are not reinventing the wheel here. Frijters et al., (2020), Birkjaer et al., (2020), Layard & Oparina, (2021), and De Neve et al., (2020) have all argued for and demonstrated the usefulness of the WELLBY. However, using WELLBYs to prioritise between policy or philanthropic interventions remains largely unexplored.

The initial work to synthesise the implications of SWB for policy is promising at this early stage (Krekel & Frijters, 2021; Global Happiness Policy Report, 2018; Global Happiness Policy Report, 2019), but existing research lacks thorough cost-effectiveness analyses. The Happier Lives Institute was set up to fill this gap and our research has shown how different interventions can be compared using SWB. For example, our research pipeline includes reports on lead exposure, pain relief, immigration reform, digital psychotherapy apps, deworming, and malaria prevention.

Notably, we have compared the cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy and cash transfers - including long-term effects and household spillovers - with SWB (McGuire et al., 2022a)[5]. We find that GiveDirectly (a charity that provides cash transfers) produces 7.5 WELLBYs per $1,000 and StrongMinds (a charity that provides task-shifted group psychotherapy) produces 71.3 WELLBYs per $1,000. In Figure 3, we illustrate how the total effect for an individual is the cumulation of the WELLBYs gained over the years.

Figure 3. Total effect for an individual of GiveDirectly and StrongMinds over time

4. Four advantages of using subjective wellbeing

There are several advantages of using subjective wellbeing (SWB), which we list below.

4.1 SWB captures and integrates the overall benefit to the individual from all of the instrumental goods provided by an intervention (e.g., health, income, empowerment, etc)

If wellbeing is ultimately what matters (i.e., different outcomes are good because they make a person’s life good), then an increase in income or empowerment will matter insomuch as it improves people’s wellbeing.[6] Hence, any benefit from an intervention, be it from health or freedom or a mix of both, should be captured in peoples’ reports of their wellbeing. There are three important consequences of this advantage that are worth mentioning.

- With SWB, we don’t have to make judgments about the relative moral weights of income, health, empowerment, freedom, or any other good. For more details about how this would be done in practice, see our framework for estimating moral weights using subjective wellbeing (Donaldson et al., 2020).

- Because SWB is ostensibly measuring what we care about, it’s easier to think about modelling and capturing indirect or second-order effects (see Open Phil’s second prompt for the worldview investigation prize). This is why our estimates of household spillovers for cash transfers rely on empirical estimates (see McGuire et al., 2022a). Similarly, this is a reason why we argue that clearly estimating the long-term benefits of interventions seems important (see McGuire et al., 2022b).

- Using SWB clarifies the importance of philosophy. We believe that choosing different moral views leads to large changes in cost-effectiveness estimates, as Plant (2022) recently argued in his philosophical review of Open Philanthropy’s cause prioritisation framework. We will expand on this soon by showing that the cost-effectiveness of the Against Malaria Foundation can change dramatically depending on your philosophical view and the way you operationalize it.

4.2 SWB is based on self-reports by the affected individuals

Humans make biased predictions about other people’s wellbeing or their own future wellbeing (Coleman, 2022). This can be a problem if evaluators make inferences about how good income and health are for people’s wellbeing (Plant, 2022). This is particularly an issue with existing health measures. The weights assigned to the badness of non-lethal health states (i.e., disability weights) in the Global Burden of Disease’s DALYs are derived from judgments made by the general population about health vignettes of diseases (Global Burden of Disease, 2022). This exposes DALYs to bias stemming from affective forecasting problems (see also a similar issue with QALYs; Dolan & Metcalf, 2012) and a reliance on healthy people’s views as to which states are more healthy than others.

4.3 SWB reveals previously under-captured benefits

Mental health problems like depression are bad because it feels extremely unpleasant to be depressed. Income measures would not capture this and health measures also seem to fail because they rely on the public’s (biased towards underestimation) impression of how bad depression is (Dolan & Meltcalfe, 2012). Mental health has a large impact on wellbeing, much larger than income, physical health, or unemployment (Clark et al., 2018). Not only does mental health have a large impact on SWB, mental health treatments can be cost-effective. For example, StrongMinds, a charity which provides task-shifted group psychotherapy in Uganda and Zambia has been rated as cost-effective by Founders Pledge (Halstead et al., 2019) and we found it to be 9 times more cost-effective than GiveDirectly, a charity that provides direct cash transfers (McGuire et al., 2022a). Similarly, we expect SWB and WELLBYs to reveal other important causes where the same issues apply. For example, pain, loneliness, and the states of freedom, empowerement, injustice, and discrimination will likely be under-captured by income or DALYs because of the aforementioned reasons.

4.4 SWB is easy to measure and widely applicable

As we mentioned in Section 2, SWB measures already exist, are well studied, and have been applied to a range of topics, circumstances, and populations. Most people in most circumstances can report their subjective wellbeing on a scale without requiring much thought (see footnote 2). Furthermore, measuring SWB outcomes only requires a minimum of a single question that can take less than a minute to answer. That is easier than a consumption survey for a subsistence farmer.[7] This point may seem trivial compared to other considerations, but the cost-value of information matters. Just as we should pursue cost-effective interventions, we should also seek to do research in a way that’s maximally informative for the minimum amount of time and resources (see Lieder et al., 2022, for a recent discussion of this).

5. Four challenges for subjective wellbeing and how to solve them

We’ve argued that subjective wellbeing (SWB) is the best option for measuring non-health, non-pecuniary benefits. It might not be perfect, as we discuss below, but to paraphrase Clark et al. (2018, chapter 1) we think it’s better to have a noisy measure of what really matters than a precise measure of something that matters less.

5.1 Comparability between SWB scales

One potential concern is whether we can compare SWB responses from different people i.e., does Alice’s 4/10 mean the same thing as Bob’s 4/10?

There is not a lot of research on this topic[8], but from the work that has been done, we expect people’s responses to be comparable. Plant (2021) argues that people answer scales in a cooperative manner by trying to use scales in the same way as others would. YouGov (2018) data suggests that people tend to assign the same 0 to 10 scores to different words describing varying levels of ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Work by Kaiser and Vendrik (2022; Figure 2) found that people use SWB scales approximately linearly, which suggests that people use scales in a similar way. However, some forthcoming work by Benjamin et al. (2021) finds that people use very different subjective scales in general (e.g., how curved is this line on a 0 to 10 scale?) which suggests subjective wellbeing scales will inherit this problem too.

However, even if interpersonal comparability of SWB scales is not perfect there are still a few solutions: (1) We can design SWB scales to better afford interpersonal comparability. For example, we could implement Ng’s (2022, chapter 6) proposal to improve comparability by explicitly including the neutral point as a universal reference. (2) If SWB scale use deviates from comparability in systematic ways, we can mathematically adjust for this.

5.2 We don’t know where the ‘neutral point’ lies on SWB scales

The neutral point is where one is neither satisfied or unsatisfied (or neither happy or unhappy). This is equivalent to a DALY of 0, but for wellbeing. At the neutral point, there is no wellbeing (i.e., one would have the same wellbeing as if they were dead or did not exist). Below this point are states worse than death in wellbeing terms. Knowing this point is crucial for estimating the value of saving a life. This complex area of the WELLBY framework is still being explored and we plan to publish further research on this area later.

5.3 Different measures of SWB might indicate different priorities

Different measures of SWB reflect different philosophies of wellbeing, which means we’re uncertain which measure of SWB to prefer. To address this uncertainty, we need to assess how much our priorities change if we use happiness versus life satisfaction[9] and ensure that SWB data corresponds with all plausible measures of wellbeing. This may mean the creation of new SWB instruments. A related issue is how to convert other SWB measures to our choice metric, but we think this can be solved as a prediction problem by collecting enough data.

5.4 There are almost no cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) using WELLBYs

This means that it is hard to tell how WELLBY results differ from previous approaches (e.g., GiveWell’s CEAs). Our goal at the Happier Lives Institute is to produce more CEAs using WELLBYs and cultivate a new sub-discipline of wellbeing science to sustain the practice.

6. Conclusion

Subjective wellbeing is a strong contender for measuring non-health and non-pecuniary benefits because it’s easy to measure, it captures all perceived benefits, it avoids others telling you how good your life is, there is already an existing (and growing) literature, and it is a reliable and valid way to measure wellbeing. WELLBYs (wellbeing-adjusted life years) provide a coherent framework for cost-effectiveness analysis to assess the value of a wide set of states like freedom, injustice, empowerment, discrimination, poverty, wealth, and health (both mental and physical).

- ^

Welfarism is the view that wellbeing is the only intrinsic good. Non-welfarism, is the view that goods besides wellbeing, perhaps equality and justice, matter intrinsically.

- ^

The median response time for subjective wellbeing questions is less than 30 seconds (ONS, 2011). And SWB questions have low non-response rates (Rässler and Riphahn, 2006), and in three of the largest SWB datasets a 10 to 100 times higher response rate than income questions (OECD, 2013).

- ^

Countries with official policies for SWB measurement include Austria, Belgium, Ecuador, Finland, Italy, Israel, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom (Durand, 2018).

- ^

Affective mental health, usually measured with depression scales, involves questions about how people feel, which will directly relate to SWB.

- ^

Our results are currently presented in terms of standard-deviation years of wellbeing gained instead of WELLBYs. This is because we combine data from multiple sources and different SWB measures in a meta-analysis. The typical output for a meta-analysis is standard deviations. One way to convert these results into WELLBYs is to find the typical standard deviation of 0-10 life satisfaction scales. In the World Happiness Reports the standard deviation is often ~2 points on the 0-10 life satisfaction scale. Therefore, we can convert each standard-deviation year into 2 life satisfaction points per year, namely, 2 WELLBYs.

- ^

The alternative for measuring non-income, non-health is to ask people how empowered, free, discriminated, or oppressed they feel or think themselves to be. However, to compare an intervention that increases freedom with one that increases health you would need to compare the value of freedom, health, and other outcomes. But these valuations would be subject to potential bias that SWB avoids.

- ^

See the OECD guidelines (2002) for measuring the food element of consumption alone: “To measure subsistence food production, all items used should be weighed and their origin established at the time meals are being prepared. Since consumption patterns usually vary from one region to another and from season to season, a nation-wide sample of households should be used, with interviews spaced evenly over a full twelve-month period. Surveys of this sort require a fairly large team of trained enumerators and supervisors, and the transport, data processing, and other administrative costs involved may also be considerable.”

- ^

The Happier Lives Institute is currently working with Caspar Kaiser and Conrad Samuelsson on a survey to test complex questions about SWB scale use such as linearity, end points, comparability, and the neutral point.

- ^

Boarini et al., (2012) find that shared determinants differ as to the degree of their influence on life satisfaction and affect but mostly have the same sign. In McGuire & Plant (2021) we found that the total effect of transfers differs by 2-13% if we use affective mental health rather than life satisfaction or happiness measures.

I really like this point. There is some initial cost of changing from the DALY/QALY approach to the WELLBY one. However, given the smaller variable cost of the WELLBY, in the longterm, the transition seems quite worth it.

SWB measures seem very useful for some types of comparisons (measuring freedom, etc) but also really inadequate for others. In particular, I worry that they over-weight the immediate effects of interventions, and underweight the long-term effects. Here are some examples:

One possible solution to all of these things would be to collect SWB data for a long period after the intervention. The problem is that SWB data have to be collected with a much higher frequency than income/health data. By their nature, SWB data are reliable when reporting on current state: all the studies of SWB validity I've seen are showing the validity when people introspect on their state of life now, not their state of life a year ago. I think it's very likely that people recalling SWB in the past would be highly biased by their current SWB. In contrast, income/health are more objective for people to recall, and they can also be collected from administrative data. So I don't think WELLBYs in practice could adequately measure effects with primarily long-term benefits and little to no short-term benefits.

Hello Karthik. Thank you for your comment. Apologies, it seems that we missed your comment at the time of posting so we’re providing our responses now.

This is not an issue with the measures, but rather how much data we can collect for them.

If you measure someone’s life satisfaction at point t, it is just like measuring someone’s income at point t, in that both are at a single point in time. If you want to analyse the effects of an intervention overtime, it doesn’t matter if it is income or life satisfaction, you need to measure the effect across time.

The advantage of income is that you’re more likely to have written records of it (bank statements, etc.) compared to reports of your subjective wellbeing. However, if a researcher didn’t record income/health/etc. (e.g. they failed to record it at a certain point in their intervention), then they have the same issue in that they would have to rely on people’s memory (for past information) or predictions (for future information).

Health outcomes are not ‘objective’ when it comes to measures of quality of health. You can remember having a disease and use the DALY score for said disease, but then you rely on the survey of people that were asked (without having the disease themselves) how ‘healthy’ or not it is to have that disease. Note that this is potentially ‘easy’ to recall not so much because of ‘objectivity’ but likely because of ‘granularity of detail’: the disease is likely a ‘binary’ state - you have covid or you don’t - and not a numerical score out of 10. Either way, this question about memory is the realm of empirical psychological work, and my point is that even if it is easier to recall it is still not a great measure.

Countries like the UK collect wellbeing measures as part of their administrative data.

Just so I answer your examples, quoted below. The general answer is “we need to measure the outcome in the long run”.

The education intervention might lead to better wellbeing in the future and wellbeing measures would capture all the potential impacts of the intervention. If you collect income or health at this very moment, you also get no difference. Why is increasing test scores good? Because it increases x or y later. Why is x or y good? Ultimately, because it increases wellbeing.

You would need to measure the effect on the SWB of the family and take everything into account. Just because the intervention increased income (but potentially affected social relationships) does not mean it was a good intervention.

Counterfactually, 20 years from now he would rate his SWB higher. Same with income or health, the effect only occurs 20 years from now (in this scenario). With health measures one could use previous data and make a prediction that “respiratory diseases cause X DALYs”. But here we could also look at data that relates SWB and respiratory diseases and see that “respiratory diseases decrease life satisfaction by X”. Same principle with income.

Great post, thanks!

Have you thought about how the WELLBY approach could be applied to animals (which cannot be polled)? One hythothesis would be:

Hi Vasco. This is a great question and one that I find personally intriguing (although I am not an expert in this area).

I'm curious about the possibility of identifying biometric indicators that correlate with subjective wellbeing scores in order to make interspecies comparisons of wellbeing. For example, Blanchfower and Bryson (2021) investigated the link between pulse and wellbeing.

At the Wellbeing Research & Policy Conference, Daniel Kahneman noted the increasing importance of 'wearables' for tracking health and wellbeing data. I think this technology could be applied to non-human animals too. I asked the team at Wild Animal Initiative about this. They're in the process of hiring a physiology research specialist, but in the meantime they said:

For the most recent thinking about interspecies comparisons of welfare, I recommend watching the recordings from the recent conference sponsored by Rethink Priorities and reading Jason Schukraft's sequence of posts on moral weights.

Thanks for sharing, I will have a look at some of those!

Does HLI have a strategy to a) get more research done using SWB scales?, and b) get more policy making based on SWB effectiveness?

I suppose it's a bit of a chicken and egg problem?

Yes for both a) and b). But the strategy is secret...

(Basically, the idea is to show using measures of how people feel can and will give different priorities and therefore we should pay more attention to it)

I am skeptical of using answers to questions such as "how satisfied are you with your life?" as a measure of human preferences. I suspect that the meaning of the answer might differ substantially between people in different cultures and/or be normalized w.r.t. some complicated implicit baseline, such as what a person thinks they should "expect" or "deserve". I would be more optimistic of measurements based on revealed preferences, i.e. what people actually choose given several options when they are well-informed or what people think of their past choices in hindsight (or at least what they say they would choose in hypothetical situations, but this is less reliable).

[I'm assuming that something like preference utilitarianism is a reasonable model of our goal here, I do realize some people might disagree but didn't want to dive into those weeds just yet.]

(I only skimmed the article, so my apologies if this was addressed somewhere and I missed it.)

Hello, Vanessa

To complement Michael's reply, I think there's been some decent work related to two of your points, which happens to all be by the same group.

In Benjamin et al. (2012; 2014a) they find that what people choose is well predicted by what they think would make them happier or more satisfied with their life -- so there may not be too much tension between these measures as is. However, if you're interested in a measure of wellbeing more in line with people's revealed preferences, then it seems your best bet may still lie within the realm of SWB. See Benjamin et al., (2014b) whose title hints at the thrust of their argument "Beyond Happiness and Satisfaction: Toward Well-Being Indices Based on Stated Preference" -- but note, that their approach doesn't mean abandoning subjective wellbeing as the approach is still based on asking people about their life. They discuss their approach to SWB more in Benjamin et al., (2021).

The difference in meaning of SWB questions is still, as we note in Section 5, an area of active exploration. For instance, some recent work finds that people will respond to ambiguously worded questions about their life's wellbeing to include considerations of how their family is doing (Benjamin et al., 2021, which contains a few other interesting findings!).

I wouldn't be surprised if we discover that we need to do some fine-tuning to make these questions more precise, but that that to me seems like the normal hard work of iterative refinement, instead of an indictment of the whole enterprise!

Hi Joel,

Thank you for the informative reply!

I think there's a big difference between asking people to rate their present life satisfaction and asking people what would make them more satisfied with their life. The latter is a comparison: either between several options or between future and present, depending on the phrasing of the questions. In a comparison it makes sense people report their relative preferences. On the other hand, the former is in some ill-posed reference frame. So I would be much more optimistic about a variant of WELLBY based on the former than on the latter.

I'm not sure I understand your point. Kahneman famously distinguishes between decision utility - what people do or would choose - and experience utility - how they felt as a result of their choice. SWB measures allow us to get at the second. How would you empirically test which is the better measure of preferences?

Suppose I'm the intended recipient of a philanthropic intervention by an organization called MaxGood. They are considering two possible interventions: A and B. If MaxGood choose according to "decision utility" then the result is equivalent to letting me choose, assuming that I am well-informed about the consequences. In particular, if it was in my power to decide according to what measure they choose their intervention, I would definitely choose decision-utility. Indeed, making MaxGood choose according to decision-utility is guaranteed to be the best choice according to decision-utility, assuming MaxGood are at least as well informed about things as I am, and by definition I'm making my choices according to decision-utility.

On the other hand, letting MaxGood choose according to my answer on a poll is... Well, if I knew how the poll is used when answering it, I could use it to achieve the same effect. But in practice, this is not the context in which people answer those polls (even if they know the poll is used for philanthropy, this philanthropy usually doesn't target them personally, and even if it did individual answers would have tiny influence[1]). Therefore, the result might be what I actually want or it might be e.g. choosing an intervention which will influence society in a direction that makes putting higher numbers culturally expected or will lower the baseline expectations w.r.t. which I'm implicitly calculating this number[2].

Another issue with polls is, how do we know the answer is utility rather than some monotonic function of utility? The difference is important if we need to compute expectations. But this is the least of the problem IMO.

Now, in reality it is not in the recipient's power to decide on that measure. Hence MaxGood are free to decide in some other way. But, if your philanthropy is explicitly going against what the recipient would choose for themself[3], well... From my perspective (as Vanessa this time), this is not even altruism anymore. This is imposing your own preferences on other people[4].

A similar situation arises in voting, and I indeed believe this causes people to vote in ways other than optimizing the governance of the country (specifically, vote according to tribal signalling considerations instead).

Although in practice, many interventions have limited predictable influence on this kind of factors, which might mean that poll-based measures are usually fine. It might still be difficult to see the signal through the noise in this measure. And, we need to be vigilant about interventions that don't fall into this class.

It is ofc absolutely fine if e.g. MaxGood are using a poll-based measure because they believe, with rational justification, that in practice this is the best way to maximize the recipient's decision-utility.

I'm ignoring animals in this entire analysis, but this doesn't matter much since the poll methodology is in applicable to animals anyway.

Would this also apply to e.g. funding any GiveWell top charity besides GiveDirectly, or would that fall into "in practice, this is the best way to maximize the recipient's decision-utility"?

I don't think most recipients would buy vitamin supplementation or bednets themselves, given cash.

I guess you could say that it's because they're not "well informed", but then how could you predict their "decision utility when well informed" besides assuming it would correlate strongly with maximizing their experience utility?

A bit off-topic, but I found GiveWell's staff documents on moral weights fascinating for deciding how much to weigh beneficiaries' preferences, from a very different angle.

I don't know much about supplements/bednets, but AFAIU there are some economy of scale issues which make it easier for e.g. AMF to supply bednets compared with individuals buying bednets for themselves.

As to how to predict "decision utility when well informed", one method I can think of is look at people who have been selected for being well-informed while similar to target recipients in other respects.

But, I don't at all claim that I know how to do it right, or even that life satisfaction polls are useless. I'm just saying that I would feel better about research grounded in (what I see as) more solid starting assumptions, which might lead to using life satisfaction polls or to something else entirely (or a combination of both).

Hi Vanessa, I really liked how specific and critical your comment was, which I think is ultimately how research can improve, so I've upvoted it :)

I'm not linked to this report but have an interest in subjective measures broadly so thought I would add a different perspective for the sake of discussion in response to the two issues your raise.

I think the fact that SWB measures differs across cultures is actually a good sign that these measures capture what they are supposed to capture. Cultures differ in e.g. values (collectivistic vs individualistic), social and gender norms, economic systems, ethics and moral. Surely some of these facets should influence how people see what a good life is, what happiness is, what wellbeing is. In fact, I would be more concerned if different people with different views and circumstances did not, as you say, 'differ substantially.'

I think these differences, attributable to culture or individual variance, are not likely to be of concern for what I would imagine would be the more common ways WELLBYs could be used. Most cost effectiveness analyses rely on RCTs or comparable designs with pre and post measures. You could look at changes within the same group of people easily pre and post and compare their differences. Or even beyond such designs, controlling for different sources of variance that we think are important (like age and gender most commonly) is not that tricky. This doesn't seem a big methodological concern to me but would be keen to hear more about how things look from your view.

What I like about the original post here is that there is caution about the uncertainties and challenges with SWB measures, e.g. comparability issues, neutral points. So I think it's only fair to point out some of the challenges for revealed preferences. In my reading, there's a long body of researcher suggesting these are stable, yet in practice your 'revealed' preference at $5 is likely to be different than at $10. Many scholars have now critiqued the notion of revealed preferences and instead suggested that we should be talking about constructed preferences. Most notably I am thinking of Itamar Simonson's work, though this as a field can be traced back at least to Slovic in the 1950s (to my knowledge).

Constructed preferences are seen as constructed in the process of making a choice - different tasks and contexts highlight different aspects of the available options, thus focusing decision-makers on different considerations that lead to seemingly inconsistent decisions (Bettman, Luce, and Payne 1998). And I think there is an argument to be made that your wellbeing can influence your constructed preferences. For instance, negative appraisals and rumination are common for low levels of wellbeing, and there is evidence to suggest that perceived choice difficulty is linked to variances for preferences (Dhar and Simonson 2003; Payne, Bettman, and Johnson 1992). Further, there is evidence broader metacognitive process influence constructed preferences, and those too can shift depending on your (lack of) happiness. So I wouldn't be surprised that your preferences vary at e.g. low vs high SWB, in fact it sounds to me like it would be important to know SWB and be able to account for it.

My claim is not "SWB is empirically different between cultures therefore SWB is bad". My claim is, I suspect that cultural factors cause people to choose different numbers for reasons orthogonal to what they actually want. For example, maybe Alice wants to be a career woman instead of her current role as a housewife (and would make choices to this effect if she had an opportunity), but she reports high life satisfaction because she feels that is expected of her (and it's not like reporting a low number would help her). Or, maybe people in Fooland consistently report higher life satisfaction than people in Baristan (because they have lower expectations of how life should be), but nobody from Baristan wants to move to Fooland and everyone from Fooland want to move to Baristan if they can (because life is actually better in Baristan).

I agree that directly comparing "pre" to "post" SWB might work okay for many interventions, because the intervention doesn't affect the confounding factors, as long as you're comparing different interventions applied to similar populations. I would still rely more on asking people directly how much this intervention helped them / how much their life improved over this period (as opposed to comparing numbers reported at different points of time)[1]. And, we should still be vigilant about situations in which the confounders cannot be ignored (e.g. interventions that cause cultural shifts). And, there might be a non-linear relationship between SWB and decision-utility which should be somehow divulged if we are averaging these numbers.

I'm guessing you are not talking about things like, how much free time you would exchange for an additional $1? Because that's consistent with constant preferences? So, Alice has $5 and Bob has $10, they are asked to choose between X and Y, and they have predictably different preferences despite the fact that post-X-Alice has the same wealth (and other circumstances) and post-X-Bob and the same for Y? And this despite somehow controlling for confounders are correlated both with the causes for Alice's and Bob's wealth and with their preferences?

I imagine such things can happen, in which case I would try to add hindsight judgements and judgements of people who experienced different circumstances into the mix. I expect that as people become more informed and experienced they roughly converge to some stable set of preferences, and the tradeoffs that don't converge are not really important. If I'm wrong and they are important, then we need to use the revealed preferences of people in those particular circumstances (which, yes, might include SWB, might also include other parameters).

Even under optimistic assumptions about SWB, this seems less noisy. Under pessimistic assumptions, I can imagine e.g. people implicitly interpreting the question as comparing their life to their neighbors (which were also affected by the intervention) or comparing their life now to their life in the past (which was still after the intervention), in which case SWB has no signal at all.

Thanks so much for replying, I learned a lot from your response and its clarity helped me update my thinking.

Thanks, the specificity here helped me understand your view better. I suppose with the examples you give -- I would expect these to be exceptions rather than norms (because if e.g. wanting to have a career was the norm, over enough time, that would tend to become culturally normative and even in the process of it becoming a more normative view the difference with a SWB measure should diminish). And more broadly, interventions that have large samples and aim for generalizability should be reasonably representative and also diminish this as a concern.

I suppose I'm also thinking about the potential difference in specific SWB scales. Something like the SWLS scale or the single item measures would not be very domain specific but scales based around the e.g. Wheel of Life tradition tell you a lot more different facets of your life (e.g. you can see high overall scale but low for job satisfaction), so it seems to me that with the right scales and enough items you can address culture or other variance even further.

Thanks again for responding with such precision. What I was unable to articulate well is that your individual preferences are not stable (or I suppose: per person, rather than across people), i.e. Alice when she has $5 will exchange a different amount of free time for an extra $1 then when Alice has $10.

I agree with everything else you've said and especially with:

I think this is a hugely underappreciated point. I think some of the SWB measures target this issue somewhat but in a limited fashion. I'd love to see more qualitative interviews and participatory / or co-production interventions. I am always surprised by how many interventions say they cannot ascertain a causal mechanism quantitatively and so do not attempt to... well, ask people what worked and didn't.

You're very welcome, I'm glad it was useful!

I'm much more pessimistic. The processes that determine what is culturally normative are complicated, there are many examples of norms that discriminate against certain groups or curtail freedoms lasting over time, and if you're optimizing for the near future then "over enough time" is not a satisfactory solution.

I don't know how those scales work, but (as I wrote in my reply to Joel), I would be much more optimistic about scales that are relative i.e. ask you to compare your well-being in situation A to situation B (whether these situations are familiar or hypothetical) rather than absolute (in which case it's not clear what's the reference frame).

This is considered a consistent preference in standard (VNM) decision theory. It is entirely consistent that U(6$ and X free time) > U(5$ and Y free time) but U(11$ and X free time) < U(10$ and Y free time).

I am not convinced about WELLBYs for a few reasons that I might comment later, but my primary response to this post is admiration at HLI for being so persistent and thorough about the value of SWB measures. I have a very strong intuition that SWB measures are invalid, but each analysis that you all do reduces that intuition little by little. It's really nice to see a really ambitious project to change one of the most fundamental tools of EA.

Hi Karthik, For what it’s worth I would be interested to hear your reasons and what sort of evidence would change your mind more than us cranking out analyses.

What would you do if Open Phil gave you a million dollars?

Would it mostly be cost effectiveness analyses? My impression is that CEAs are good if you decide SWB is the right metric and then deciding what is the best SWB intervention.

I am not sure that I see clearly in your argument for SWB (which is compelling) what the next steps are. What is the problem you are solving exactly and how?

Connected, but separate question: Do you have an idea of how to make DALYS and QALYS and WELLBYS commensurable? Do you have an idea for how to compare these metrics apples for apples?

Re: next steps, maybe check out their page Our story so far, scroll down to '2022':

re: comparing the metrics apples for apples, (my impression of) their point is that they simply aren't commensurable, because (to quote the relevant part of the OP)

It doesn't seem very practical to come up with Q/DALY-to-WELLBY "conversion rates" for all 440 health states in the GBD to adjust for the over/underweighting due to affective forecasting.

Thanks for this!

The reason i brought up interventions that they would want to fund is that I figured that they were interested in improving the WELLBY metric. If they are planning on being a regranter, then thats a whole different story to me.

I agree that they might very well be incommensurable. However, I suspect that different organizations will want to use different metrics, and someone like OpenPhil or one day GiveWell might have to be able to compare the two somehow. d

No worries (:

You're right that metric conversions are of interest to some orgs; for instance GiveWell and HLI both use moral weights to convert between averting death and increasing income. Other orgs don't; for instance TLYCS looks at 4 core outcomes (lives saved, life-years added, income gained, carbon removed) and maintain them separately, and Open Phil have their "worldview buckets". I lean towards converting metrics mostly for the reasons Nuno writes about, but I'm also swayed by Holden's argument that cluster thinking (a main driver of worldview diversification) is more robust w.r.t. handling Knightian uncertainty, so I'm left unsure which approach ("to convert or not to convert?") is best for EA as a whole.

Interesting stuff and out of my depth! Seems like something I should nerd out on for awhile :) Anywhere you suggest I could start?

If you found this post helpful, please consider completing HLI's 2022 Impact Survey.

Most questions are multiple-choice and all questions are optional. It should take you around 15 minutes depending on how much you want to say.

It'd be quite game-changing to see politicians using WELLBY to measure the success of their time in office.

Would go from it being a GDP-optimization game to it being a mind control game...