abrahamrowe

Bio

Principal — Good Structures

I previously co-founded and served as Executive Director at Wild Animal Initiative, and was the COO of Rethink Priorities from 2020 to 2024.

Posts 24

Comments235

Topic contributions1

Yeah, that is a great point.

Relatedly, one thing I've been thinking about since posting this is how much Distinction feels relevant to EA (though I'm hesitant to cite continental philosophy on the EA Forum of all places!)

I think specifically, EA sometimes concentrates different types of power (e.g. financial, cultural/social, etc) into funders, and doing that is inherently distorting. E.g. I'm thinking about things like: having funders be keynote speakers at events, etc. that elevates funder social position relative to other people.

My experience of the animal welfare space, say, where the deference issues don't come up as much (though has plenty of other funder-related issues!) is that the funders have lots of financial power, but besides two specific people, aren't given much social/cultural power, and most the social/cultural power is held by people who don't distribute funding. I also have heard of things like funders being considered for speaking at conferences, and people pushing back on it a bit out of these kinds of concerns. I think maybe some more healthy skepticism about mixing power types could be helpful?

That's too bad! I'll give this feedback to Every.org as they are a moderately aligned nonprofit themselves, and are really receptive to feedback in my experience. FWIW, using them saves organizations a pretty massive amount of bureaucracy / paperwork / compliance-y stuff, so I hope there is a way to use them that can be beneficial for the donors.

I think that the animal welfare space is especially opaque for strategic reasons. For example, most of the publicly available descriptions of corporate animal welfare strategy are, in my opinion, not particularly accurate. I think most of the actual strategy becoming public would make it significantly less effective. I don't think it is kept secret with a deep amount of intentionality, but more like there is a shared understanding among many of the best campaigners to not share exactly how they are working outside a circle of collaborators to avoid strategies losing effectiveness.

I think outside organizations' ability to evaluate the effectiveness of individual corporate campaigning organizations (including ACE unfortunately) is really low due to this (I think that evaluating ecosystems of organizations / the intervention as a whole is easier though).

(I don't really want to engage much on this because I found it pretty emotionally draining last time — I'll just leave this comment and stop here):

I think asking for feedback prior to publishing these seems really important. To be clear, I'm very sympathetic to the overall claim! I suspect that most published estimates of the impact of marginal dollars in the farmed animal space are way too high (maybe even by orders of magnitude)

I also think the items you raise are important questions for Sinergia to answer!

But, I think getting feedback would be really helpful for you:

- You cite multiple places where Sinergia claims impact, but you cite evidence to the contrary, such as company statements on their sites either existing prior to Sinergia's claimed date, or not existing at all.

- The experience of corporate campaigners universally is that the degree to which you should take company statements about their animal welfare commitments seriously is relatively low. It's just a regular fact of corporate campaigning in many countries that companies have statements on their websites that they either don't follow or don't intend to follow. Often, companies have weaselly language that lets them get out of a commitment, e.g. "we aspire to do X by Y year," etc.

- The language in company statements matter a ton — when I ran corporate campaigns, a major US restaurant company I was campaigning on put up a verbatim version of the Better Chicken Commitment with all of the specifics removed (e.g. "reduce stocking density" instead of "reduce stocking density to X lbs/sqft") and did nothing in their supply chain. This allowed them to tell journalists / others that we were just lying that they had not made the commitment. I worry that Google translating pages loses nuance that might matter here. Google Translating Brazilian law also seems like a huge stretch as evidence — and taking the law at face value as a non-Brazilian lawyer (and not evidence about the interpretation and enforcement of the law) seems like a mistake.

- Getting a commitment on the website is important, but it's only a portion of work. Actually getting the company to make the change is way more work.

- I know nothing about the JBS case, but can tell you that there are many times where a company has a commitment, then behind the scenes the actual work is several years of getting them to honor it. It seems completely plausible, and even routine, that the actual impact credit should go to an organization working to get a company to act on an existing policy, as opposed to getting them to put up the policy in the first place. I don't know anything about Sinergia's claims here, but seems totally plausible that much of their impact comes from this invisible work that you wouldn't learn about without asking them.

I suspect that in your critique, some of your claims are warranted, but others might have much more complicated stories behind them, such as an organization getting a company to actually follow through on a commitment, or getting a law to be enforced. I think that feedback would help draw out where these critiques are accurate, and where they are missing the mark.

Equal Hands — 2 Month Update

Equal Hands is an experiment in democratizing effective giving. Donors simulate pooling their resources together, and voting how to distribute them across cause areas. All votes count equally, independent of someone's ability to give.

You can learn more about it here, and sign up to learn more or join here. If you sign up before December 16th, you can participate in our current round. As of December 7th, 2024 at 11:00pm Eastern time, 12 donors have pledged $2,915, meaning the marginal $25 donor will move ~$226 in expectation to their preferred cause areas.

In Equal Hands’ first 2 months, 22 donors participated and collectively gave $7,495.01 democratically to impactful charity. Including pledges for its third month, that number will likely increase to at least 24, and $10,410.01

Across the first two months, the gifts made by cause area and pseudo-counterfactual effect (e.g. if people had given their own money in line with their voting, rather than following the democratic outcome) has been:

- Animal welfare: $3,133.35, a decrease of $1,662.15

- Global health: $1,694.85, a decrease of $54.15

- Global catastrophic risks: $2,093.91, an increase of $1,520.16

- EA community building: $319.38, an increase of $179.63

- Climate change: $253.52, an increase of $16.52

Interestingly, the primary impact has been money being reallocated from animal welfare to global catastrophic risks. From the very little data that we have, this primarily appears to be because animal welfare-motivated donors are much more likely to pledge large amounts to democratic giving, while GCR-motivated donors are more likely to sign up (or are a larger population in general), but are more likely to give smaller amounts.

- I’m not sure why exactly this is! The motivation should be the same regardless of cause area for small donors — in expectation, the average vote has moved over $200 to each donor’s preferred causes across both of the first two months, so I would expect it to be motivating for donors from various backgrounds, but maybe GCR-motivated donors are more likely to think in this kind of reasoning.

- GCR donors haven’t had as high-retention over the first three months of signups, so currently the third month looks like it might look a bit different — funding is primarily flowing out of animal welfare, and going to a mix of global health and GCRs.

The total administrative time for me to operate Equal Hands has been around 45 minutes per month. I think it will remain below 1 hour per month with up to 100 donors, which is somewhat below what I expected when I started this project.

We’d love to see more people join! I think this project works best by having a larger number of donors, especially people interested in giving above the minimum of $25. If you want to learn more or sign up, you can do so here!

Nice! And yeah, I shouldn't have said downstream. I mean something like, (almost) every intervention has wild animal welfare considerations (because many things end up impacting wild animals), so if you buy that wild animal welfare matters, the complexity of solving WAW problems isn't just a problem for WAI — it's a problem for everyone.

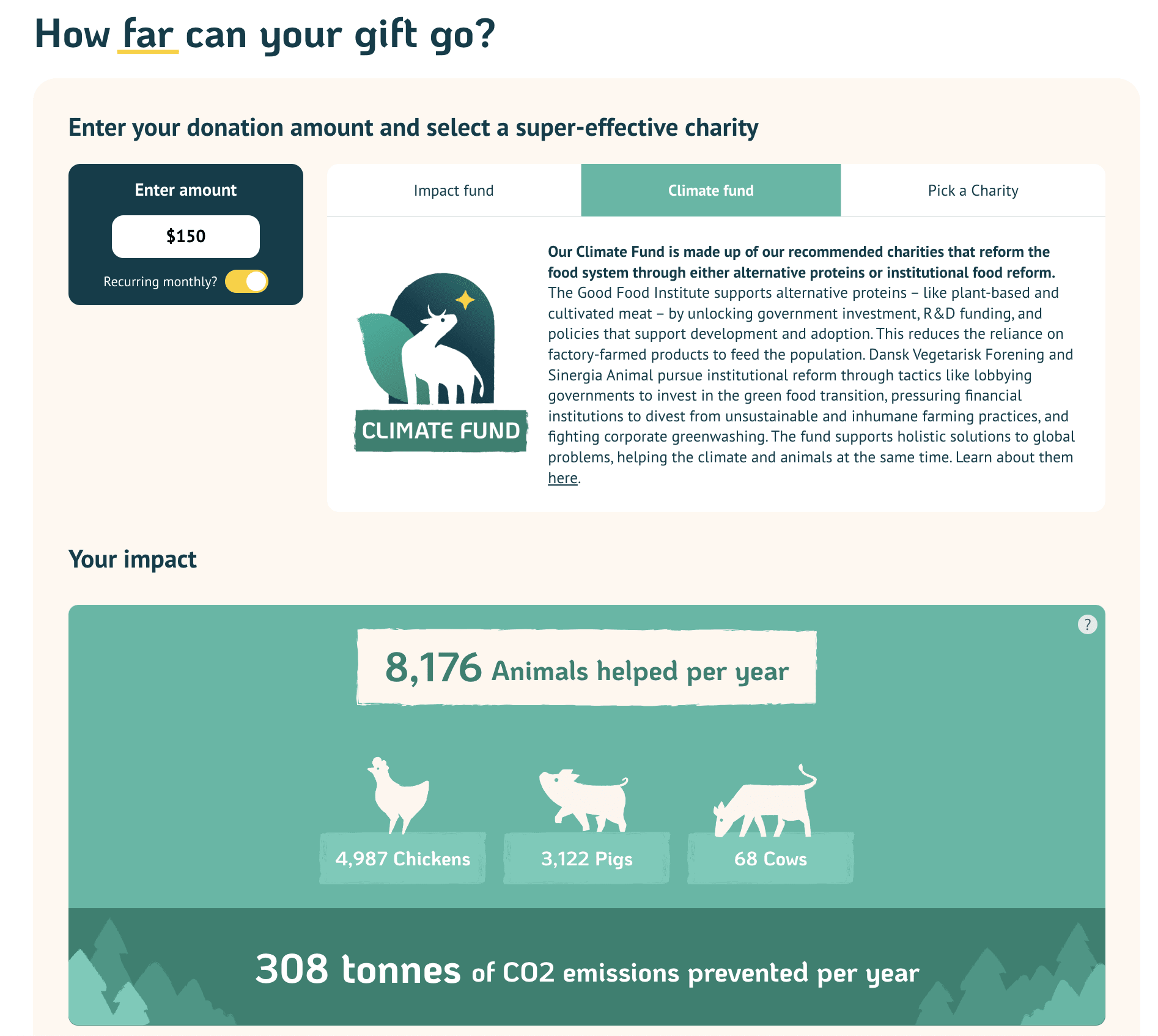

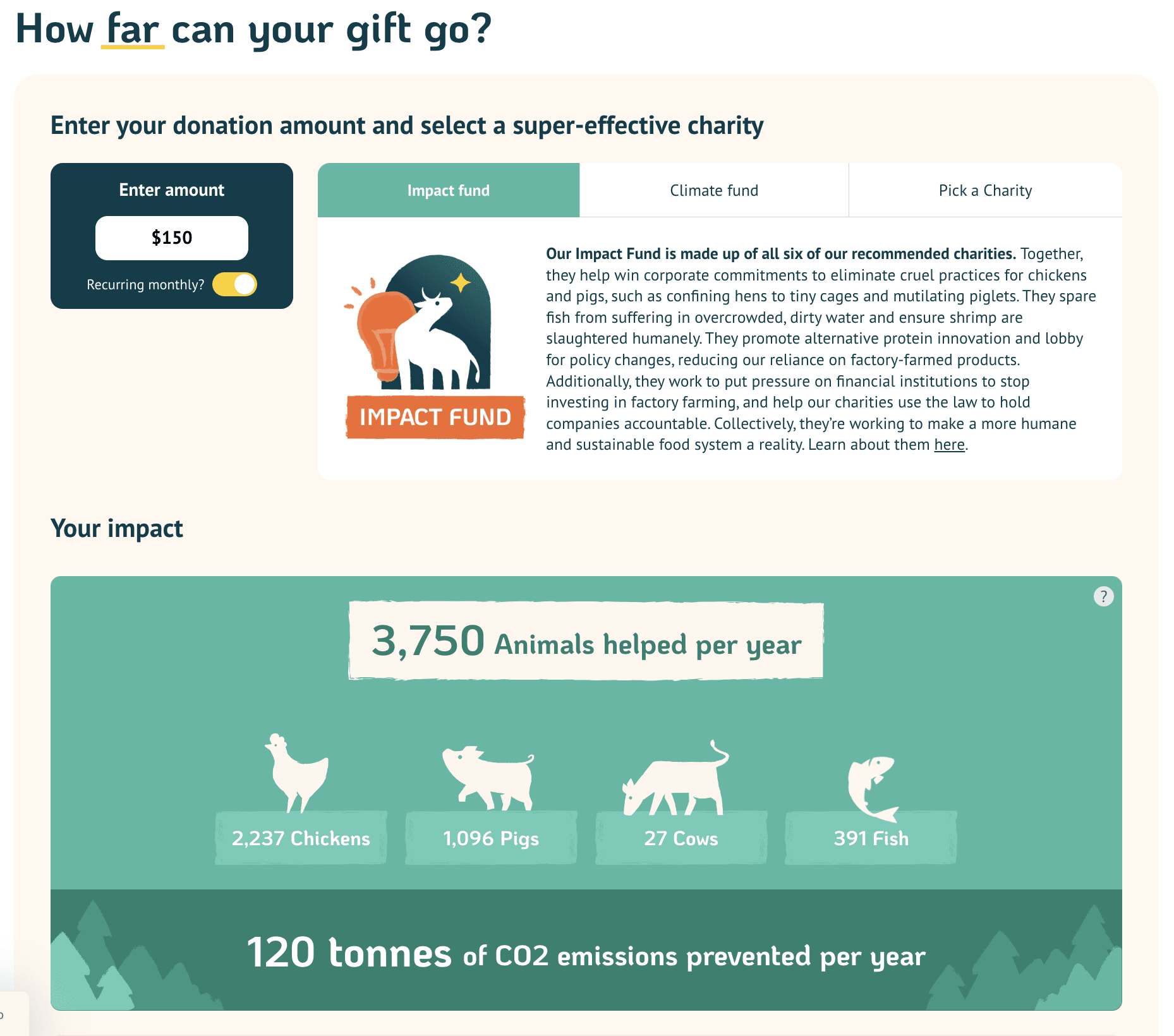

Minor question - I noticed that the website states for the climate fund that the same donation will help a lot more animals than the impact fund (over 2x as many - and mostly driven by chickens and pigs). I know the numbers are likely low confidence, but just curious how you're thinking about those, as to me it was unintuitive to have one labelled "impact fund" that straightforwardly looks worse on animal impacts than the climate fund (and also worse on the climate side!). I didn't quite understand why this was happening from looking at the calculations page (though from the charities in each, I definitely have the sense that the impact fund is better for animals!)

Not commenting on WAI specifically, I kind of dislike the "wild animal suffering in not very tractable" meme because it feels like it emerged before anyone ever even tried to figure out how tractable it was, and before basically any science happened in the space, but has just stuck, based on armchair philosophizing by non-scientists (me among them, to be clear). It sometimes feels a bit like saying curing polio is intractable before anyone ever tried to look into making a vaccine or think about what we could do to try to cure it — we're not going to know the tractability of interventions until we actually look into it in detail, and people with the right kind of expertise to evaluate WAW's tractability have barely started doing so.

It's also just a massive space — it seems pretty unreasonable to say that, given that hundreds of quadrillions of animals at least as complicated as insects, live vastly different lives across the world in thousands of kinds of biomes/ecosystems, etc, that helping ~none of them is going to be possible without at least trying to look into it for a minute.

My personal belief is that we will probably have good wild animal welfare interventions sooner than we'll have good marginal uses for farmed animal money beyond current interventions, which suggests that the research seems pretty worth it.

I also think that wild animal welfare just remains a problem for ~everyone, given that wild animal welfare impacts are downstream from most other interventions, so solving it should be a big priority. Insofar as people think that wild animal suffering is intractable because of uncertain impacts of your intervention on other wild animals, surely that would basically just apply to anything you do in the world that impacts wild animals (which is probably basically everything). If you buy the case for wild animals mattering morally, but think that downstream effects make it impossible to act on it, most charity seems to get stuck.