Jack_S

Posts 4

Comments25

Yeah, this is a big challenge in the corporate campaign space, especially in places with weak legal systems and low enforcement. But this links to why corporate campaigns can be more effective than policy campaigns. Getting policy commitments on paper in a country with poor rule of law might have very limited impact because no-one's incentivised to uphold the laws, but there's a decent chance that an international, or niche company with high reputational awareness is incentivised to try and maintain a higher welfare supply chain.

So you might get a high-end hotel chain in a lower-income country that genuinely wants to shift to cage-free eggs after a campaign. They make a commitment, you arrange meetings with them and their suppliers to help them meet these commitments, and track whether their numbers match up. This can work even if the legal system functions poorly.

People in the Bharat Initiative for Accountability (BIA) and Global Food Partners (GFP) are doing stuff like this in India and Southeast Asia. It takes loads of work on both the supply and demand side, as you might expect, which might cut against the higher-end effectiveness estimates, but it's definitely something people have in mind.

People from these teams spoke about this recently on the How I Learned To Love Shrimp podcast (here and here).

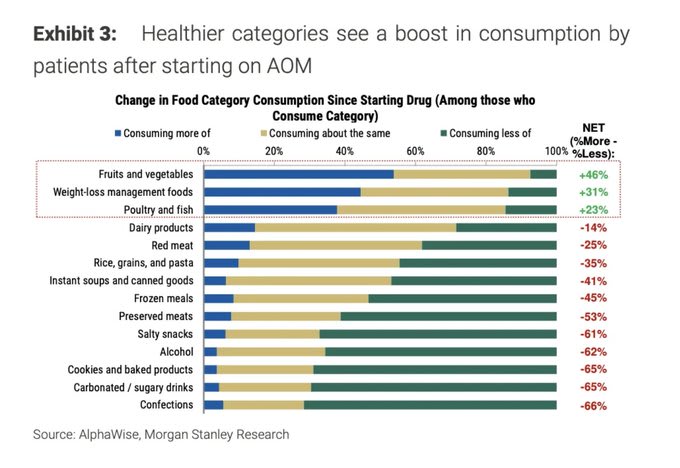

https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/obesity-drugs-food-industry This study doesn't make Semaglutide look especially promising for animal welfare (increase in poultry and fish), but I'm not sure how rigorous the research is, so I'd be excited to read other sources.

Thanks for both of your responses (@Jacob_Peacock and @abrahamrowe). I was going to analyse the podcast in more detail to resolve our different understandings, but I think @BruceF 's response to the piece clarifies his views on the "negative/positive" PTC hypothesis. The views that he would defend are: (negative) "First, if we don’t compete on price and taste, the products will stay niche, and meat consumption will continue to grow." and (positive) "Second, if we can create products that compete on price and taste, sales will go up quite a lot, even if other factors will need to be met to gain additional market share.”

I expect that these two claims are less controversial, albeit with "quite a lot" leaving some ambiguity.

My initial response was based on my assumption that everyone involved in alt protein realises that PTC-parity is only one step towards widespread adoption. But I agree that it's worth getting more specific and checking how people feel about Abraham's "how much of the work is PTC doing- 90% vs 5%?" question.

I assume if you surveyed/ interviewed people working in the space, there would be a fairly wide range of views. I doubt if people have super-clear models, because we're expecting progress in the coming years to come on multiple fronts (consumer acceptance, product quality, product suitability, policy, norms), and to mutually reinforce each other, but it would be worth clarifying so that you can better identify what you're arguing against.

From my own work on alt-protein adoption in Asia I sense that PTC-parity is only a small part of the puzzle, but it would also be far easier to solve the other pieces if we suddenly had some PTC-competitive killer products, so PTC interact with other variables in ways that make it difficult to calculate.

Overall, I stand by my criticism that I don't think the positive PTC-hypothesis as you frame it is commonly held. But I'd like to understand better what the views are that you're critiquing. It would be interesting to see your anecdotal evidence supported- what people actually think when they say they (previously) bought into PTC, and who these people are. It could be true, for example, that people who work in PBM startups tend to believe more strongly that a PTC-competitive product will transform the market, but people working on the market side tend to realise how many barriers there are to adoption beyond these factors.

Thanks for this article, I agree with a lot of the takeaways, and I think that more research into developing an evidence-based theory of change for short- and long-term uptake of alt proteins is very valuable.

But I think the problem with arguing against an informal hypothesis is that I don't think you're actually arguing against a commonly-held view.

This is how you frame it:

"The price, taste, and convenience (PTC) hypothesis posits that if plant-based meat is competitive with animal-based meat on these three criteria, the large majority of current consumers would replace animal-based meat with plant-based meat."

I'll call it the "positive-PTC hypothesis", the idea that if we achieve PTC-parity, the market will automatically shift. I don't think anyone in the space holds this view strongly. To the extent that they do stress PTC over other factors, the sources you quote seem to put more emphasis on the 'negative-PTC' hypothesis- achieving PTC-parity is a necessary but not sufficient criteria for people to start considering PBM.

Szejda et al. say:

"... only after a food product is perceived as delicious, affordable, and accessible will the average consumer consider its health benefits, environmental impact, or impact on animals in the decision to purchase it."

This negative-PTC hypothesis also seems to be implied more to some extent in the Friedrich 80k podcast you refer to. He also says explicitly that he doesn't think everyone would switch to PTC-matched PBM (hence the need for cell-cultured meat).

There's a bit of positive-PTC in the GFI research program RFP (2019) claim that "alternative proteins become the default choice" (both cultured and PBM), but even then it's not exclusively PTC, they also refer to these proteins winning out on perceptions of health and sustainability, and requiring product diversity.

As well as this, every source you quote, and every paper I've ever read on PB meat acceptance, also stresses a bunch of other factors besides PTC. In particular, the main report you associate with PTC (Szejda et al. 2020) stresses familiarity throughout the report. "While many people have favorable attitudes toward sustainability and animals, the core-driver barriers to acting on these attitudes are too strong for most. More than anything, products that meet taste, price, convenience, and familiarity expectations will reduce these barriers". Familiarity in itself could go a long way to explaining the negative results in all the studies you refer to: all are comparing an unfamiliar product with a familiar product.

So I'd argue that very few people in this space actually support the PTC hypothesis as you frame it. Few people think that PTC-parity is sufficient for widespread PBM uptake.

Having said that, I think there probably is an interesting, genuine divergence of views with people who hold a PTC+ hypothesis and those who hold a more "holistic" view. So if a diverse range of alt proteins achieve parity in price, taste and convenience, while also being positively perceived in terms of familiarity, health, environment, status, safety etc., some might believe that there will be an inevitable shift to these products, while others would think that meat and carnism is so embedded within our cultural and social norms that even if we get overwhelming good alternatives, the majority of the population would still be very unlikely to stop eating meat. It's an interesting question, but one that I don't think you've answered in this piece.

If I recall, it was only really in the 2010s, following the release of this study (catchily named HPTN 052), that we realised that ART/ ARV was so effective in stopping HIV transmission, so I think that was a justifiable oversight.

Assuming that prices will remain constant seems to be a genuine issue - I think we need to think about this more when we look at cost-effectiveness generally - but I have an inkling as to why this might be common.

In Mead Over's (Justin's colleague) excellent course on HIV and Universal Health Coverage, we modelled the cost effectiveness of ART compared to different interventions. The software package involved constant costs for ART (and second line ART) as a default setting, and didn't assume that there would be price reductions. I didn't ask why this was, but after adding price reductions to the model for my chosen country (Chad), I realised that the model then incentivises delaying universal ART within a country, and instead focusing on other interventions which are less likely to decrease in cost over time.

Delaying might be wise in some contexts, but I'm sure many health ministers are just looking for excuses to delay action (letting other countries bring the price down first), so politics doubtless plays a role.

I haven't got a very well calibrated model, but I'm still fairly optimistic about alt proteins becoming increasingly commercially viable. I would update very little on 2022 being a fairly bad year for a few reasons:

- I don't think the article's claim that 'sales of PBM declined significantly in 2022' is actually true. According to the lastest GFI plant-based meat report: "...global dollar sales of plant-based meat grew eight percent in 2022 to $6.1 billion, while sales by weight grew five percent." In Europe, sales grew by 6%, so it's really just the US.

- In the US, "estimated total plant-based meat dollar sales increased slightly by 2% while estimated pound (lb) sales decreased by 4%" (GFI, 2023), so a very marginal decline in demand. I think the narrative that the market collapsed in 2022 is more due to the more significant decline in home/ refrigerated purchasing of PBM, and perhaps because Beyond Meat had an awful year.

- Other metrics are looking okay:

- Total invested capital in alt protein is still comparable with other food sectors, with major increases in cultivated and fermented meat investment.

- Government investment is growing and locked-in as part of multi-year programs in many countries

- Many new production facilities are springing up, which should reduce prices, especially for fermented and cultivated products.

- I think we've reached the turning point for national safety approvals for cultivated meat, and I expect more (such as China and Japan) in 2023-2024

- There has been some pretty considerable investment in certain emerging markets (APAC and MENA) - Even if it has been a bad year in some respects, it's been a bad year for everyone. Conventional meat sectors have also suffered in 2022- particularly in the UK and EU. And growing tech sectors have also slowed - quantum computing investment also flattened off from a rapid growth trajectory.

So I wouldn't update too much on 2022's slowdown- it's a combination of macroeconomic factors, Russia-Ukraine, high interest rates and rising energy prices that have reduced investment, and inflation that's led to reduced consumption.

As for your question of whether alternative proteins will take off. I'm optimistic. I think we've entered a situation where:

- Many conventional/ institutional food producers have bought into alt proteins, so there's less institutional resistance

- Most governments are at least partly supporting the transition to alt proteins, especially import-dependent countries with food security issues like Israel, Singapore and the UEA

- Young people across a lot of the world are increasingly into alt proteins (especially milks), so the demographic shift will work in favour of alt proteins over the next decade

I feel that we have the right incentives and technology to produce super tasty, affordable alternatives for various consumer types, and when we get these products, the market should start to grow.

The reasons I could be wrong might be:

- We'll continue to lack those killer products at an affordable price. The market will be dominated by poor, low-cost products, giving alt protein a worse reputation among many normal consumer groups.

- It's only ever going to be a niche market. Almost everyone actually prefers conventional meat, and most consumers are more resistant to change than we currently think. Cell-cultivated meat will be seen as the only viable alternative, and people will continue consuming conventional meat until cell-cultivated meat hits price parity.

I'd argue that EA is quite bad at something like: "Engaging a broad group of relevant stakeholders for increased impact". So getting loads of non-EA people on your side, and finding ways to work together with multiple, potentially misaligned orgs, governments and individuals.

Don't want to overstate this- some EA orgs do this well. Charity Entrepreneurship include stakeholder engagement in their program, for example. But it seems neglected in the EA space more generally.

Yeah, makes sense. I just don't know why it's not just: "It's conceivable, therefore, that EA community building has net negative impact."

If you think that EA is/ EAs are net-negative value, then surely the more important point is that we should disband EA totally / collectively rid ourselves of the foolish notion that we should ever try to optimise anything/ commit seppuku for the greater good, rather than ease up on the community building.

I spent some time researching this topic recently (blog post link). It seemed an odd paradox - why does the one-child policy not seem to have that much of an impact on the birth rates?

The answer is quite simple but weird that no-one knows about it. It's mainly that the pre-One Child Policy population control policies in China in the 1970s were more restrictive than you think, and the 1980s policies were de facto more liberal. You can see this 1970s crash on any visualisation- from 6 to 2.7 births per women in 7 years! (1970-1977). A big chunk of this was because the legal marriage age shot up in most areas, to 25/23 for rural women/men, and 28/25 for urban. You get a big gap where people, especially in villages, would previously be having kids at 18 and suddenly weren't.

Thanks to Deng's reforms, the 1980s were more open in many ways, marriage was restored to the normal age, divorce was liberalised, so the one child policy was implemented partly to stop a resurgence of the birth rate! So alongside a big wave of sterilisations, you also get the "catch-up" of people now allowed to marry and have kids. Also, after some pushback, the OCP wasn't that strictly enforced in the late 1980s, especially in rural areas, so you get some provinces where 3 or 4 kids stayed normal. Some people also took advantage of Deng's reforms to leave their village, get divorced and have a kid with someone else. So you don't see a big crash in the birth rate in the 1980s, and China averaged 2.5 kids per woman in the mid 1980s.

The OCP was more strictly enforced in the 1990s, so you see the crash from 2.5 to 1.5 births per women then. You also start seeing the extreme sex ratio imbalances. Now that the 1990s (56% male) cohort has reached parent-age, that's one reason the current crash in the birth rate is so extreme. China would probably be seeing drops in the birth rate in the absence of any population control policies, but there's no chance it would be this extreme.