Follow up to Monday's post Why Hasn't Effective Altruism Grown Since 2015?. See discussions on r/scc, LessWrong and EA Forum.

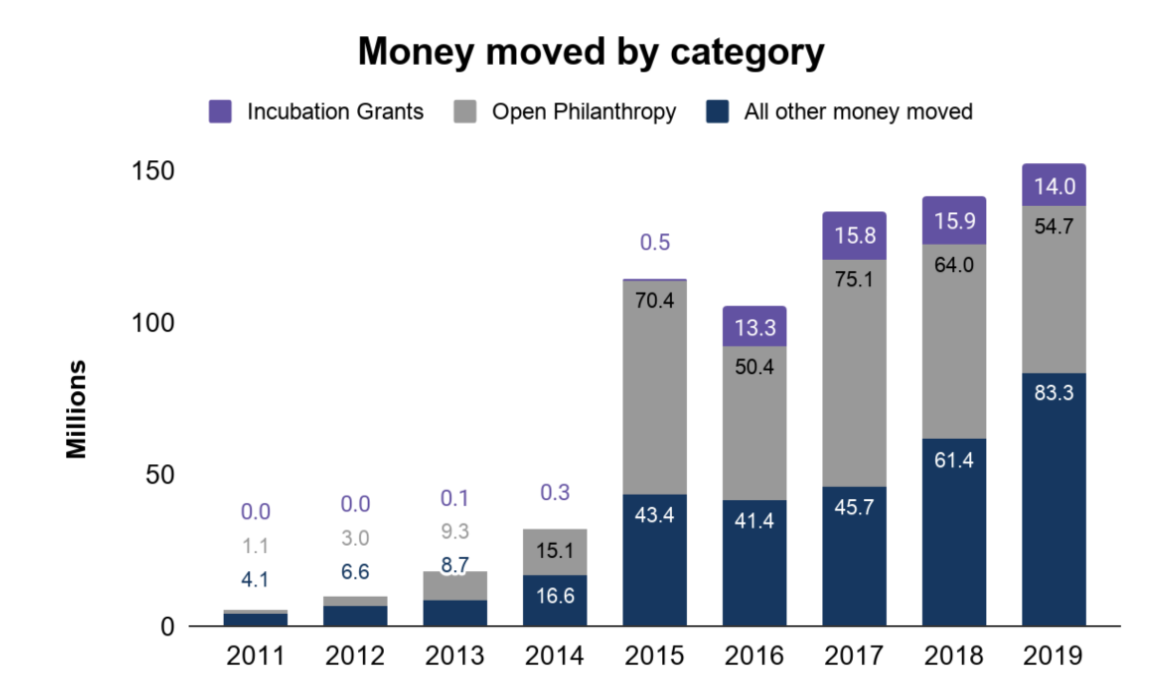

Here's a chart of GiveWell's annual money moved. It rose dramatically from 2014 to 2015, then more or less plateaued:

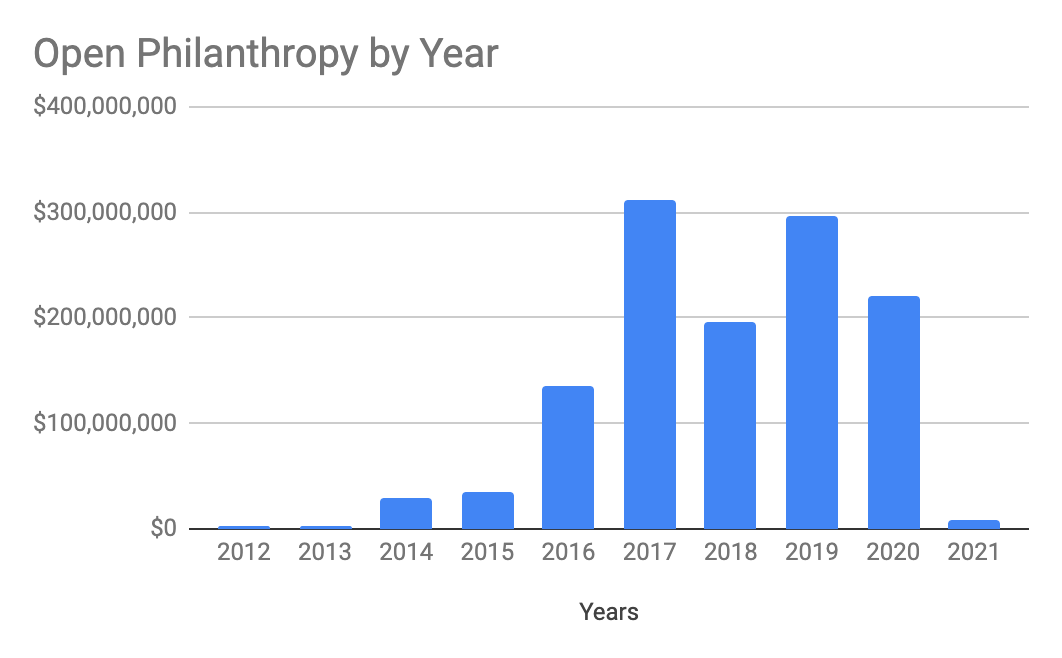

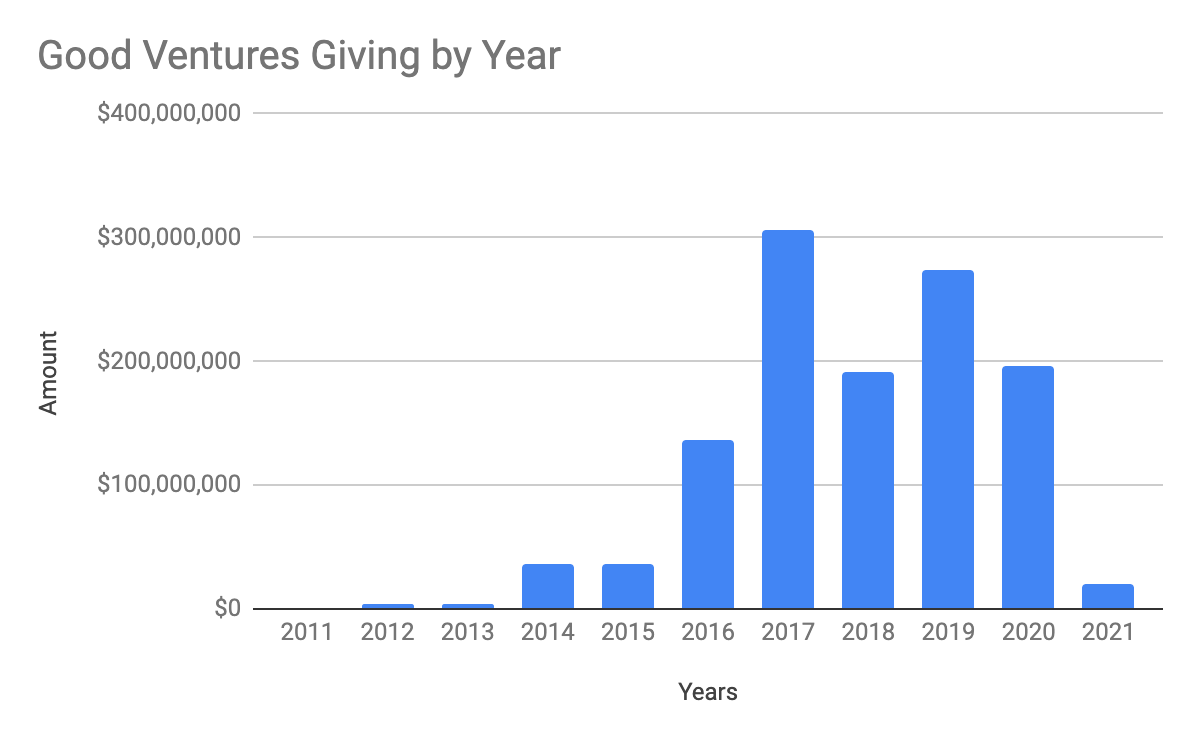

Open Philanthropy doesn't provide an equivalent chart, but they do have a grants database, so I was able to compile the data myself. It peaks in 2017, then falls a bit and plateaus:

(Note that the GiveWell and Open Philanthropy didn't formally split until 2017. GiveWell records $70.4m from Open Philanthropy in 2015, which isn't included in Open Philanthropy's own records. I've emailed them for clarification, but in the meantime, the overall story in the same: A rapid rise followed by several years of stagnation. Edit: I got a reply explaining that years are sometimes off by 1, see [0].)

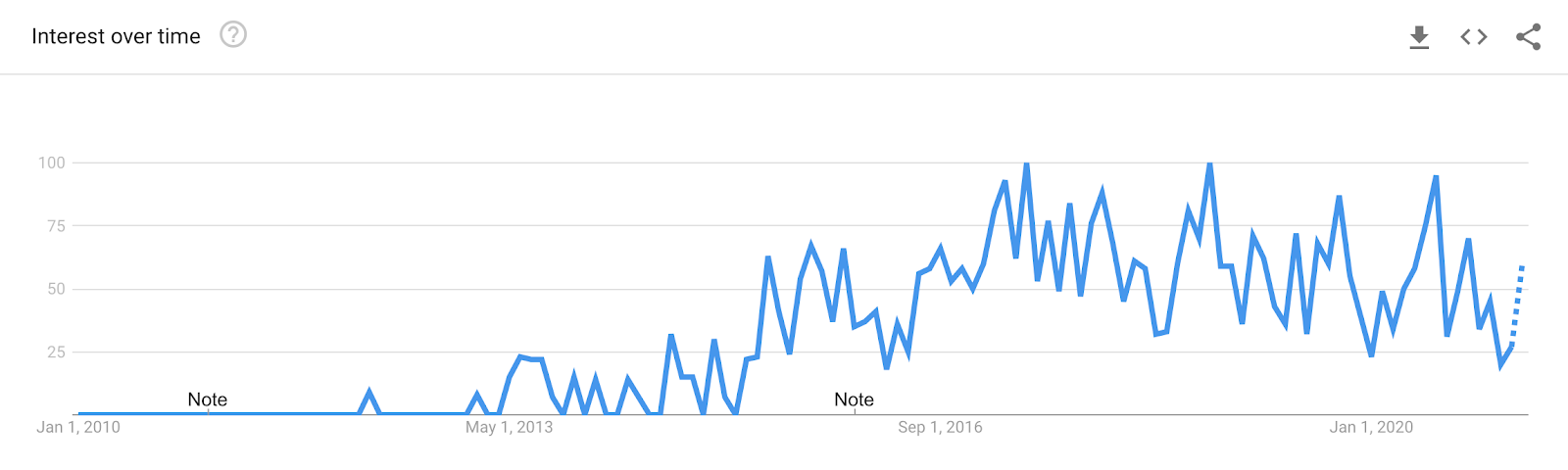

Finally, here's the Google Trends result for "Effective Altruism". It grows quickly starting in 2013, peaks in 2017, then falls back down to around 2015 levels. Broadly speaking, interest has been about flat since 2015.

If this data isn't surprising to you, it should be.

Several EA organizations work on actively growing the community, have been funding community growth for years and view it as an active priority:

- 80,000 Hours: The Problem Profiles page lists "Building effective altruism" as a "highest-priority area", right up there with AI and existential risk.

- Open Philanthropy: Effective Altruism is one of their Focus Areas. They write "We're interested in supporting organizations that seek to introduce people to the idea of doing as much good as possible, provide them with guidance in doing so, connect them with each other, and generally grow and empower the effective altruism community."

- EA Funds: One of the four funds is dedicated to Effective Altruism Infrastructure. Part of its mission reads: "Directly increase the number of people who are exposed to principles of effective altruism, or develop, refine or present such principles"

So if EA community growth is stagnating despite these efforts, it should strike you as very odd, or even somewhat troubling. Open Philanthropy decided to start funding EA community growth in 2015/2016 [1]. It's not as if this is only a very recent effort.

As long as money continues to pour into the space, we ought to understand precisely why growth has stalled so far. The question is threefold:

- Why was growth initially strong?

- Why did it stagnate around 2015-2017?

- Why has the money spent on growth since then failed to make a difference?

Here are some possible explanations.

1. Alienation

Effective Altruism makes large moral demands, and frames things in a detached quantitative manner. Utilitarianism is already alienating, and EA is only more so.

This is an okay explanation, but it doesn't explain why growth initially started strong, and then tapered off.

2. Decline is the Baseline

Perhaps EA would have otherwise declined, and it is only thanks to the funding that it has even succeeded in remaining flat.

I'm not sure how to disambiguate between these cases, but it might be worth spending more time on. If the goal is merely community maintenance, different projects may be appropriate.

3. The Fall LessWrong and Rise of SlateStarCodex

Several folk sources indicate the LessWrong went through a decline in 2015. A brief history of LessWrong says "In 2015-2016 the site underwent a steady decline of activity leading some to declare the site dead." The History of Less Wrong writes:

Around 2013, many core members of the community stopped posting on Less Wrong, because of both increased growth of the Bay Area physical community and increased demands and opportunities from other projects. MIRI's support base grew to the point where Eliezer could focus on AI research instead of community-building, Center for Applied Rationality worked on development of new rationality techniques and rationality education mostly offline, and prominent writers left to their own blogs where they could develop their own voice without asking if it was within the bounds of Less Wrong.

Specifically, some blame the decline on SlateStarCodex:

With the rise of Slate Star Codex, the incentive for new users to post content on Lesswrong went down. Posting at Slate Star Codex is not open, so potentially great bloggers are not incentivized to come up with their ideas, but only to comment on the ones there.

In other words, SlateStarCodex and LessWrong catered to similar audiences, and SlateStarCodex won out. [2]

This view is somewhat supported by Google Trends, which shows a subtle decline in mentions of "Less Wrong" after 2015, until a possible rebirth in 2020.

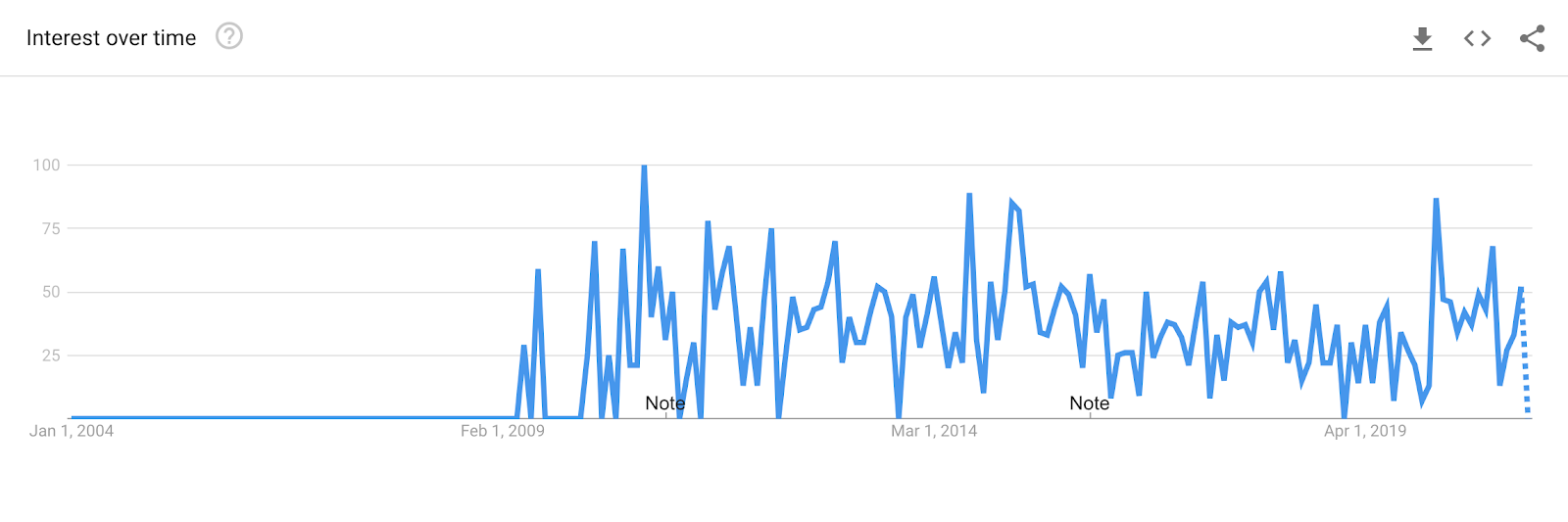

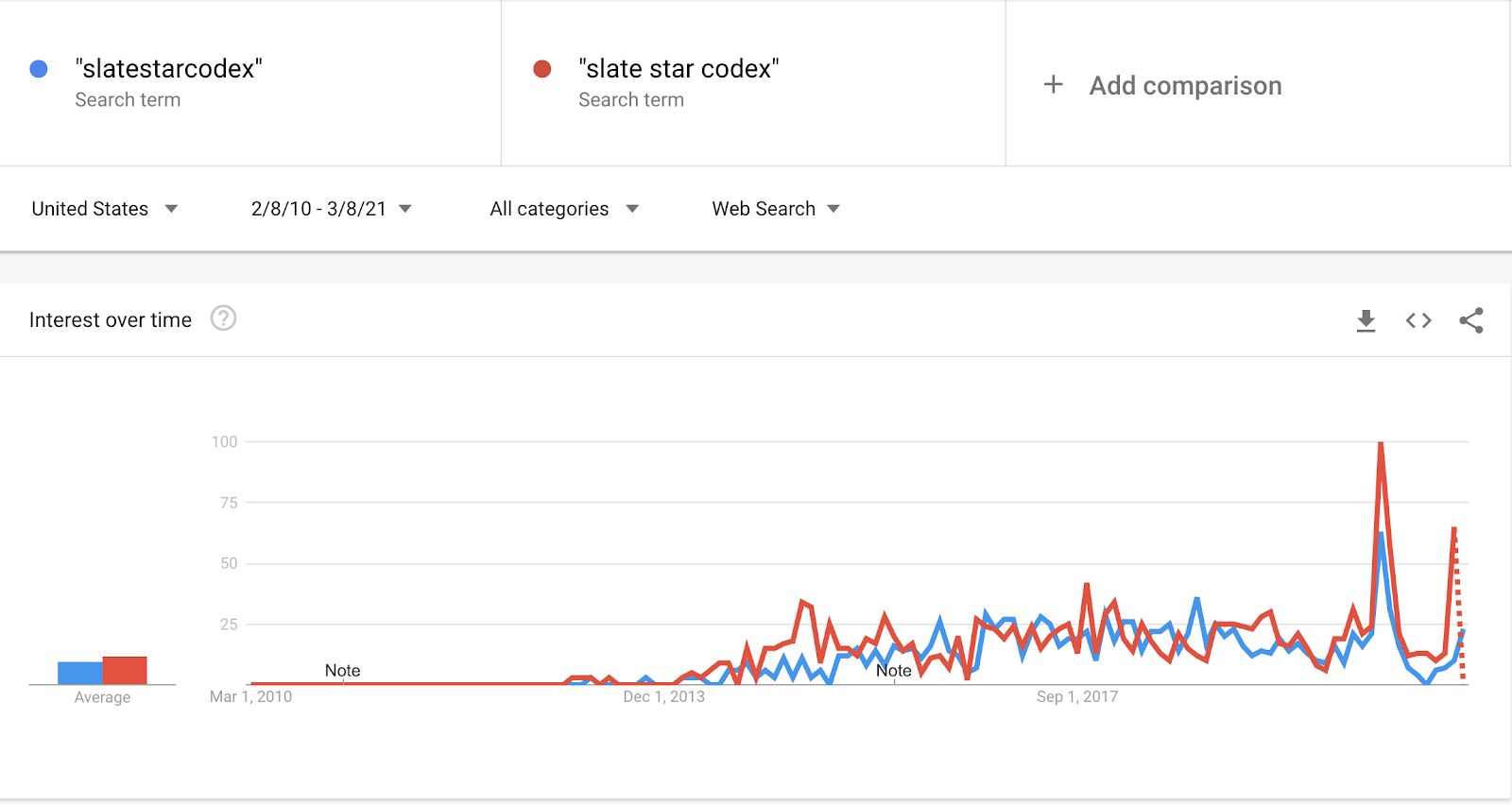

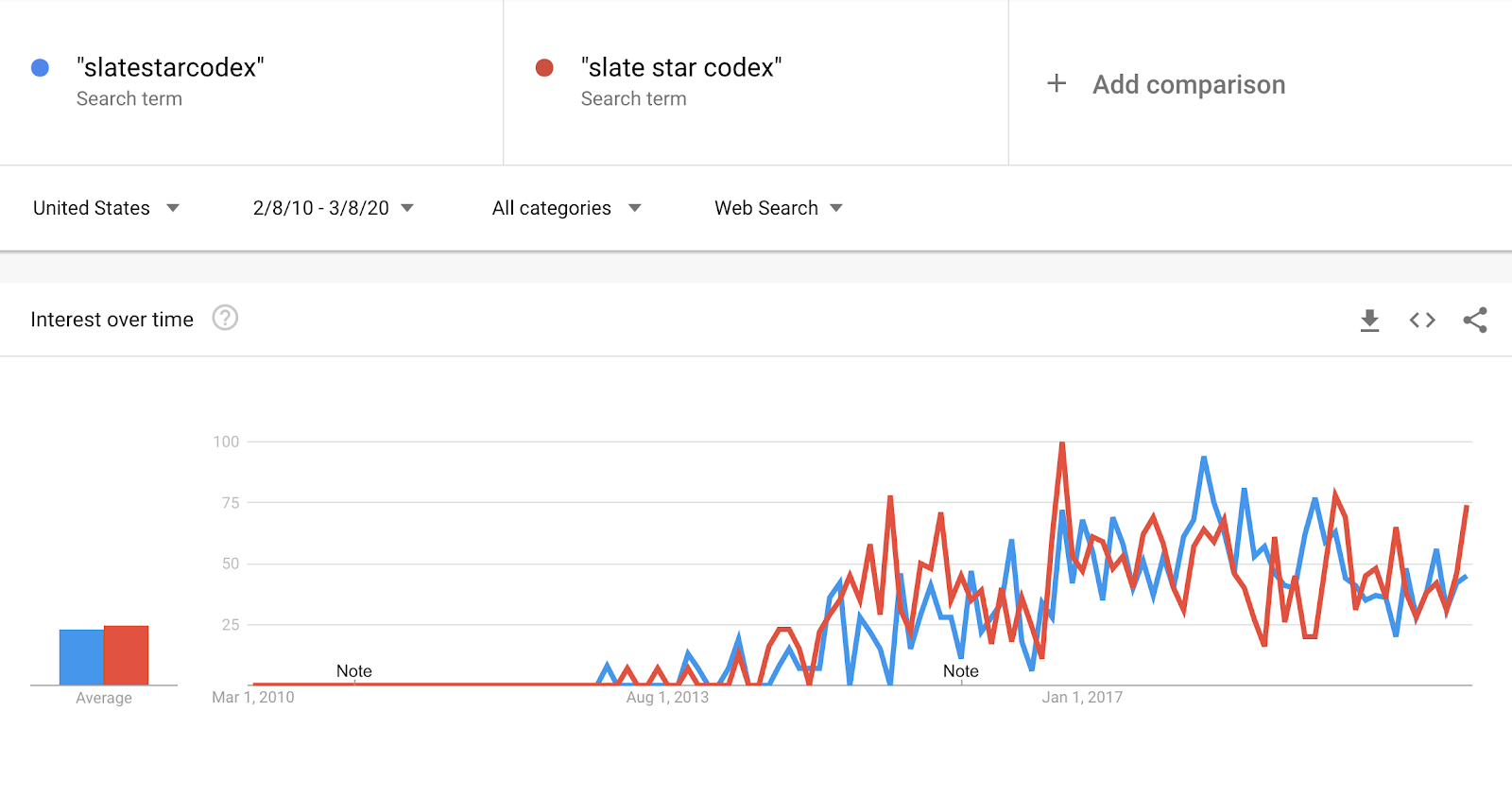

Except SlateStarCodex also hasn't been growing since 2015:

The recent data is distorted by the NYT incident, but basically the story is the same. Rapid rise to prominence in 2015, followed by a long plateau. So maybe some users left for Slate Star Codex in 2015, but that doesn't explain why neither community saw much growth from 2015 - 2020.

And here's the same chart, omitting the last 12 months of NYT-induced frenzy:

4. Community Stagnation was Caused by Funding Stagnation

One possibility is that there was not a strange hidden cause behind widespread stagnation. It's just that funding slowed down, and so everything else slowed down with it. I'm not sure what the precise mechanism is, but this seems plausible.

Of course, now the question becomes: why did Open Philanthropy giving slow? This isn't as mysterious since it's not an organic process: almost all the money comes from Good Ventures which is the vehicle for Dustin Moskovitz's giving.

Did Dustin find another pet cause to pursue instead? It seems unlikely. In 2019, they provided $274 million total, nearly all of which ($245 million) went to Open Philanthropy recommendations.

Let's go a level deeper and take a look at the Good Ventures grant database aggregated by year:

It looks a lot like the Open Philanthropy chart! They also peaked in 2017, and have been in decline ever since.

So this theory boils down to:

- The EA community stopped growing because EA finances stopped growing

- EA finances stopped growing because Good Ventures stopped growing

- Good Ventures stopped growing because the wills and whims of billionaires are inscrutable?

To be clear, the causal mechanism and direction for the first piece of this argument remains speculative. It could also be:

- The EA community stopped growing

- Therefore, there was limited growth in high impact causes

- Therefore, there was no point in pumping more money into the space

This is plausible, but seems unlikely. Even if you can't give money to AI Safety, you can always give more money to bed nets.

5. EA Didn't Stop Growing, Google Trends is Wrong

Google Trends is an okay proxy for actual interest, but it's not perfect. Basically, it measures the popularity of search queries, but not the popularity of the websites themselves. So maybe instead of searching "effective altruism", people just went directly to forum.effectivealtruism.org and Google never logged a query.

Are there other datasets we can look at?

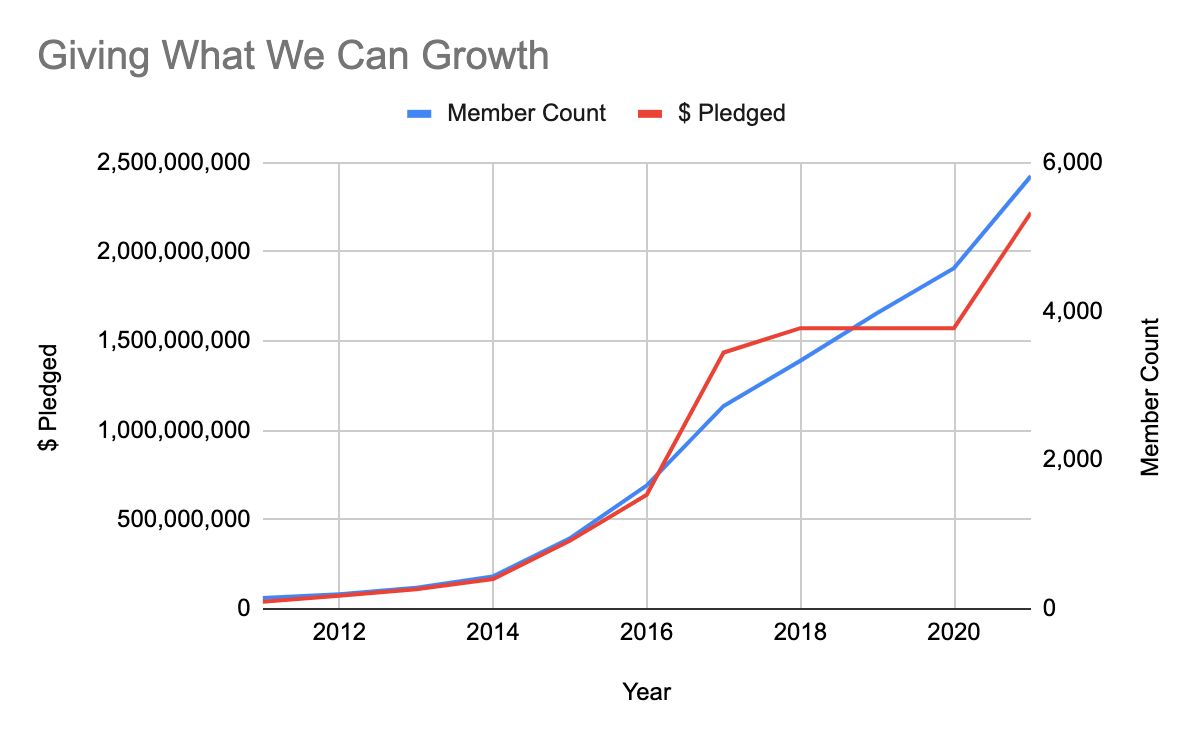

Giving What We Can doesn't release historical results, but I was able to use archive.org to see their past numbers, and compiled this dataset of money pledged [3] and member count:

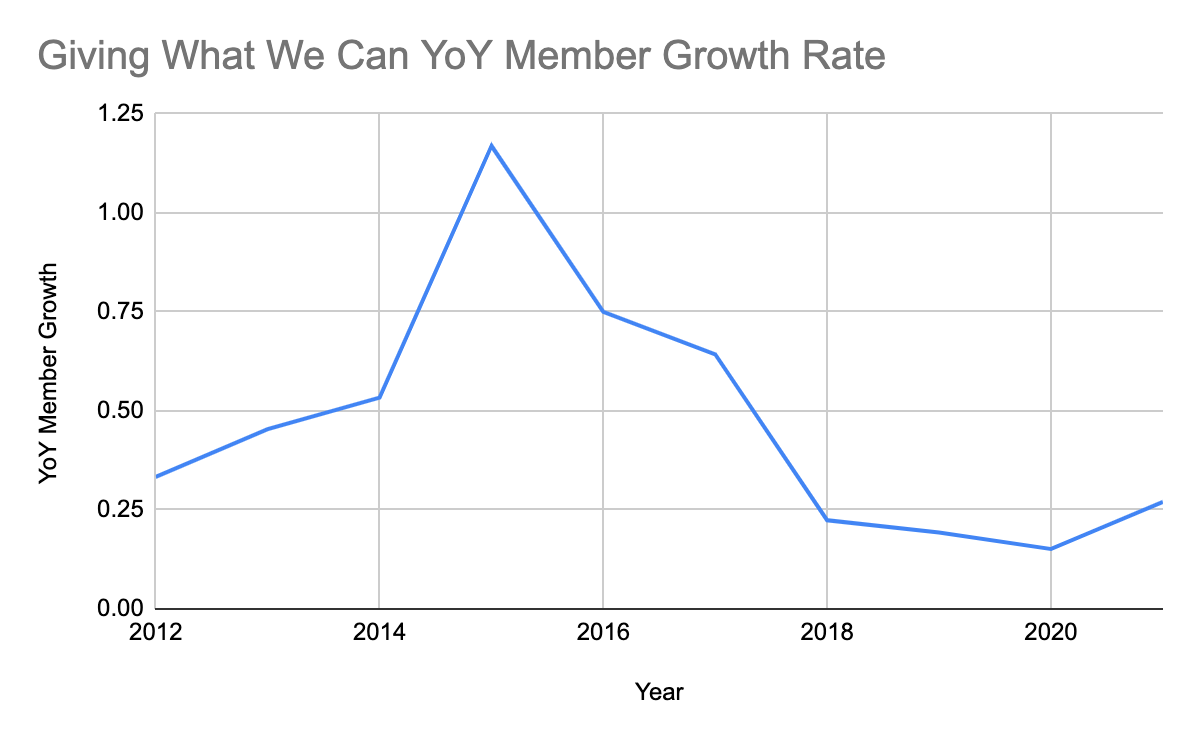

So is the entire stagnation hypothesis disproved? I don't think so. Google Trends tracks active interest, whereas Giving What We Can tracks cumulative interest. So a stagnant rate of active interest is compatible with increasing cumulative totals. Computing the annual growth rate for Giving What We Can, we see that it also peaks in 2015, and has been in decline ever since:

To sum up:

- Alienation is not a good explanation, this has always been a factor

- EA may have declined more if not for the funding

- SlateStarCodex may have taken some attention, but it also hasn't grown much since 2015

- Funding stagnation may cause community stagnation; the causal mechanism is unclear

- Giving What We Can membership has grown, but it measures cumulative rather than active interest. Their rate of growth has declined since 2015.

A Speculative Alternative: Effective Altruism is Innate

You occasionally hear stories about people discovering LessWrong or "converting" to Effective Altruism, so it's natural to think that with more investment we could grow faster. But maybe that's all wrong.

I think a formative moment for any rationalist-- our "Uncle Ben shot by the mugger" moment, if you will-- is the moment you go "holy shit, everyone in the world is fucking insane." [4]

That's not exactly scalable. There will be no Open Philanthropy grant for providing experiences of epistemic horror to would-be effective altruists.

Similarly, from John Nerst's Origin Story:

My favored means of procrastination has often been lurking on discussion forums. I can't get enough of that stuff ...Reading forums gradually became a kind of disaster tourism for me. The same stories played out again and again, arguers butting heads with only a vague idea about what the other was saying but tragically unable to understand this.

....While surfing Reddit, minding my own business, I came upon a link to Slate Star Codex. Before long, this led me to LessWrong. It turned out I was far from alone in wanting to understand everything in the world, form a coherent philosophy that successfully integrates results from the sciences, arts and humanities, and understand the psychological mechanisms that underlie the way we think, argue and disagree.

It's not that John discovered LessWrong and "became" a rationalist. It's more like he always has this underlying compulsion, and then eventually found a community where it could be shared and used productively.

In this model, Effective Altruism initially grows quickly as proto-EAs discover the community, then hits a wall as it saturates the relevant population. By 2015, everyone who might be interested in Effective Altruism has already heard about it, and there's not much more room for growth no matter how hard you push.

One last piece of anecdotal evidence: Despite repeated attempts, I have never been able to "convert" anyone to effective altruism. Not even close. I've gotten friends to agree with me on every subpoint, but still fail to sell them on the concept as a whole. These are precisely the kinds of nerdy and compassionate people you might expect to be interested, but they just aren't. [5]

In comparison, I remember my own experience taking to effective altruism the way a fish takes to water. When I first read Peter Singer, I thought "yes, obviously we should save the drowning child." When I heard about existential risk, I thought "yes, obvious we should be concerned about the far future". This didn't take slogging through hours of blog posts or books, it just made sense. [6]

Some people don't seem to have that reaction at all, and I don't think it's a failure of empathy or cognitive ability. Somehow it just doesn't take.

While there does seem to be something missing, I can't express what it is. When I say "innate", I don't mean it's true from birth. It could be the result of a specific formative moment, or an eclectic series of life experiences. Or some combination of all of the above.

Fortunately, we can at least start to figure this out through recollection and introspection. If you consider yourself an effective altruist, a rationalist or anything adjacent, please email me about your own experience. Did Yudkowsky convert you? Was reading LessWrong a grand revelation? Was the real rationalism deep inside of you all along? I want to know.

I'm at applieddivinitystudies@gmail.com, or if you read the newsletter, you can reply to the email directly. I might quote some of these publicly, but am happy to omit yours or share it anonymously if you ask.

Data for Open Philanthropy and Good Ventures is available here. Data for Giving What We Can is here. If you know how Open Philanthropy's grant database accounts for funding before it formally split off from GiveWell in 2017, please let me know.

Disclosure: I applied for funding from the EA Infrastructure Fund last week for an unrelated project.

Footnotes [0] Open Philanthropy writes:

Hi, thanks for reaching out.

Our database's date field denotes a given grant's "award date," which we define as the date when payment was distributed (or, in the case of grants paid out over multiple years, when the first payment was distributed). Particularly in the case of grants to organizations based overseas, there can be a short delay between when a grant is recommended/approved and when it is paid/awarded. (For more detail on this process, including average payment timelines, see our Grantmaking Stages page.) In 2015/2016, these payment delays resulted in top charity grants to AMF, DtWI, SCI, and GiveDirectly totaling ~$44M being paid in January 2016 and falling under 2016 in your analysis even as GiveWell presumably counted those grants in its 2015 "money moved" analysis.

Payment delays and "award date" effects also cause some artificial lumpiness in other years. For example, some of the largest top charity grants from the 2016 giving season were paid in January 2017 (SCI, AMF, DtWI) but many of the largest 2017 giving season grants were paid in December 2017 (Malaria Consortium, No Lean Season, DtWI). This has the effect of artificially inflating apparent 2017 giving relative to 2018. Other multi-year grants are counted as awarded entirely in the month/year the first payment was made -- for example, our CSET grant covering 2019-2023 first paid in January 2019. So I wouldn't read too much into individual year-to-year variation without more investigation.

Hope this helps.

[1] For more on OpenPhil's stance on EA growth, see this note from their 2015 progress report:

Effective altruism. There is a strong possibility that we will make grants aimed at helping grow the effective altruist community in 2016. Nick Beckstead, who has strong connections and context in this community, would lead this work. This would be a change from our previous position on effective altruism funding, and a future post will lay out what has changed. [emphasis mine]

[2] For what it's worth, the vast majority of SlateStarCodex readers don't actually identify as rationalist or effective altruists.

[3] My Giving What We Can dataset also has a column for money actually donated, though the data only goes back to 2015.

[4] I'm conflating effective altruism with rationalism in this section, but I don't think it matters for the sake of this argument.

[5] For what it's worth, I'm typically pretty good at convincing people to do things outside of effective altruism. In every other domain of life, I've been fairly successful at getting friends to join clubs, attend events, and so on, even when it's not something they were initially interested in. I'm not claiming to be exceptionally good, but I'm definitely not exceptionally bad.

But maybe this shouldn't be too surprising. Effective Altruism makes a much larger demand than pretty much every other cause. Spending an afternoon at a protest is very different from giving 10% of your income.

Analogously, I know a lot of people who intellectually agree with veganism, but won't actually do it. And even that is (arguably) easier than what effective altruism demands.

[6] In one of my first posts, I wrote:

Before reading A Human's Guide to Words and The Categories Were Made For Man, I went around thinking "oh god, no one is using language coherently, and I seem to be the only one seeing it, but I cannot even express my horror in a comprehensible way." This felt like a hellish combination of being trapped in an illusion, questioning my own sanity, and simultaneously being unable to scream. For years, I wondered if I was just uniquely broken, and living in a reality that no one else seemed to see or understand.

It's not like I was radicalized or converted. When I started reading Lesswrong, I didn't feel like I was learning anything new or changing my mind about anything really fundamental. It was more like "thank god someone else gets it."

When did I start thinking this way? I honestly have no idea. There were some formative moments, but as far back as I can remember, there was at least some sense that either I was crazy, or everyone else was.

I respond here: https://worldspiritsockpuppet.com/2021/03/09/why-does-ads-think-ea-hasnt-grown.html

Tldr: I agree the 'top of the funnel' seems to not be growing (i.e. how many people are reached each year). This was at least in part due to a deliberate shift in strategy. I think the 'bottom' of the funnel (e.g. money and people focused on EA) is still growing. Eventually we'll need to get the top of the funnel growing again, and people are starting to focus on this more.

Around 2015, DGB and The Most Good You Can Do were both launched, which both involved significant media attention that aimed to reach lots of people (e.g. two TED talks). 80k was also focused on reaching more people.

After that, the sense was that the greater bottleneck was taking all these newly interested people (and the money from Open Phil), and making sure that results in actually useful things happening, rather than reaching even more people.

(There was also some sense of wanting to shore up the intellectual foundations, and make sure EA is conveyed accurately, rather than as "earn to give for malaria nets", which seems vital for its long-term potential. There was also a shift towards niche outreach, rather than mass media - since mass media seems better for raising donations to global health, but less useful for something like reducing GCBRs, and although good at reaching lots of people, wasn't as effective as the niche stuff.)

E.g. in 2018, 80k switched to focusing on our key ideas page and podcast, which are more about making sure already interested people understand our ideas than reaching new people; Will focused on research and niche outreach, and is now writing a book on longtermism. GWWC was scaled down, and Toby wrote a book about existential risk.

This wasn't obviously a mistake since I think that if you track 'total money committed to EA' and 'total number of people willing to change career (or take other significant steps)', it's still growing reasonably (perhaps ~20% per year?), and these metrics are closer to what ultimately matter. (Unfortunately I don't have a good source for this claim and it relies on judgement calls, though Open Phil's resources have increased due to the increase in Dustin Moskovitz's net worth; several other donors have made a lot of money; the EA Forum is growing healthily; 80k is getting ~200 plan changes per year; the student groups keep recruiting people each year etc.)

One problem is that if the top of the funnel isn't growing, then eventually we'll 'use up' the pool of interested people who might become more dedicated, so it'll turn into a bottleneck at some point.

And all else equal, more top of funnel growth would be better, so it's a shame we haven't done more.

My impression is that people are starting to focus more on growing the top of the funnel again. However, I still think the focus is more on niche outreach, so you'd need to track a metric more like 'total number of engaged people' to evaluate it.

Scott Alexander has a very interesting response to this post on reddit: see here.

Another indicator: Wikipedia pageviews show fairly stable interest in articles on EA and related topics over the last five years.

Great share!

I weakly upvoted this for the second section, which is a discussion I've had with many people in person and is something I'm glad to see in writing. But I found the title offputting given the very modest amount of evidence presented in support of the claim.

There are a huge number of things you could check to gauge the total size of the EA movement. You chose GiveWell's total funding, Google Trends data, and the growth of Giving What We Can.

(These are all reasonable things to choose, but I don't think they are collectively decisive enough to merit a title as strongly-worded as "why hasn't effective altruism grown?" I'm really just objecting to the title here, rather than the spirit or execution of this project.)

The last number is solid evidence of weaknesses in community building strategy: CEA acknowledges that they should have put more staff time into Giving What We Can post-2016 And when Luke Freeman took over as the project's first full-time leader in years, GWWC saw faster growth (in absolute terms) than ever before. The rate of growth wasn't high compared to 2016, but it's encouraging that someone was able, within a few months, to break a record set by a larger team working full-time on GWWC when there was (presumably) more low-hanging fruit available to pick.

As for the other items:

Some examples of things that I believe have been growing, with numbers where I can easily find them:

I wish I had more data easily to hand on some of these figures, but I'd bet at 10:1 on any one of them being higher in 2020 than 2015. And while none of them are slam-dunk evidence that EA is definitely "growing" by any reasonable definition of the word, I think they collectively paint a clear picture.

I fear that most of these metrics aren't measures of EA growth, so much as of reaping the rewards of earlier years' growth. They seem compatible with a picture where EA grew a lot until 2015 and then these EAs slowly became more engaged, moved into different roles and produced different outcomes, without EA engaging significantly more new people since 2015.

We have some concrete insight about the 'lag' between people joining EA and different outcomes based on EA Survey data:

- On engagement, looking at years in EA and self-reported level of engagement, we can see that it appears to take some years for people to become highly engaged. Mean engagement continues to increase up until 5-6 years in EA, at which point it plateaus. (Although, of course, this is complicated by potential attrition, i.e. people who aren't engaged dropping out of earlier cohorts. We'll talk more about this in this year's series).

- The mean length of time between someone first hearing about EA and taking the GWWC pledge (according to 2019 EAS data) is 1.16 years (median 1 year). There are disproportionately more new EAs in the sample though, since (germane to this discussion!) EA does seem to have consistently been growing year on year (although per the above this could also be confounded somewhat by attrition) and of course people who just heard of EA in the last year couldn't have taken the GWWC pledge more than 1 year after they first heard of EA. So it may be that a more typical length of time to take the pledge is a little longer.

- Donations: these arguably have a lower barrier to entry compared to other forms of engagement, yet still increase dramatically with more time in EA.

Of course, this is likely somewhat confounded by the fact that people who have spent more time in EA have also spent more time developing their career and so their ability to donate, but the same confound could account for observed increase in EA outputs over time even if EA weren't growing.

This seems like it could be true for some of the figures, but not all. I'd strongly expect "number of active EA groups" to correlate with "number of total people engaged in EA". The existence of so many groups may come from people who joined in 2015 and started groups later, but many group leaders are university students, so that can't be the whole story.

In this case, do you think it's likely that there are about as many group members as before, spread across more groups? Or maybe there are more group members, but the same number of total people engaged in EA, with a higher % of people in groups than before?

I think this applies to growth in local groups particularly well. As I argued in this comment above, local groups seem like a particularly laggy metric due to people usually starting local groups after at least a couple of years in EA. While I've no doubt that many of the groups that have been founded by people who joined since 2015*, I suspect that even if we cut those people out of the data, we'd still see an increase in the number of local groups over that time frame- so we can't infer that EA is continuing to grow based on increase in local group numbers.

*Indeed, we should expect this because most people currently in the EA community (at least as measured by the EA Survey) are people who joined since 2015. In each EA survey, the most recent cohorts are almost always much larger than earlier cohorts (with the exception of the most recent cohort of each survey since these are run before some EAs from that year will have had a chance to join). See this graph which I previously shared, from 2019 data, for example:

(Of course, this offers, at best, an upper bound on growth in the EA movement, since earlier cohorts will likely have had more attrition).

----

There's definitely been a very dramatic increase in the percentage of EAs who are involved in local groups (at least within the EA Survey sample) since 2015 (the earliest year we have data for).

In EAS 2019 this was even higher (~43%) and in EAS 2020 it was higher still (almost 50%).

So higher numbers of local group members could be explained by increasing levels of engagement (group membership) among existing EAs. (One might worry, of course, that the increase in percentage is due to selective attrition, but the absolute numbers are higher than 2015 as well.)

Unfortunately we don't have good data on the number of local group members, because the measures in the Groups Survey were changed between 2019-2020. On the one measure which I was able to keep the same (total number of people engaged by groups) there was a large decline 2019-2020, but this is probably pandemic-related.

University group members are mostly undergraduates, meaning they are younger than ~22. This implies that they would have been younger than 18 in 2017, and there was almost no one like that on the 2017 survey. And they would have been under 16 in 2015, although I don't think we have data going back that far. I can think of one or two people who might have gotten involved as 15-year-olds in 2015, but it seems quite rare. Is there something I'm missing?

I'm not sure where you are disagreeing, because I agree that many people founding groups since 2015 will in fact have joined the movement later than 2015. Indeed, as I show in the first graph in the comment you're replying to, newer cohorts of EA are much larger than previous cohorts, and as a result most people (>60%) in the movement (or at least the EA Survey sample[^1]) by 2019 are people who joined post-2015. Fwiw, this seems like more direct evidence of growth in EA since 2015 than any of the other metrics (although concern about attrition mean that it's not straightforward evidence that the total size of the movement has been growing, merely that we've been recruiting many additional people since 2015).

My objection is that pointing to the continued growth in number of EA groups isn't good evidence of continued growth in the movement since 2015 due to lagginess (groups being founded by people who joined the movement in years previous). It sounds like your objection is that since we also know that some of the groups are university groups (albeit a slight minority) and university groups are probably mostly founded by undergraduates, we know that at least some of the groups founded since 2015 were likely founded by people who got into EA after 2015. I agree this is true, but think we still shouldn't point to the growth in number of new groups as a sign of growth in the movement because it's a noisy proxy for growth in EA, picking up a lot of growth from previous years. (If we move to pointing to separate evidence that some of the people who founded EA groups probably got into EA only post 2015, then we may as well just point to the direct evidence that the majority of EAs got into EA post-2015!)

[^1]: I don't take this caveat to undermine the point very much because, if anything I would expect the EA Survey sample to under-represent newer, less engaged EAs and over-represent EAs who have been involved longer.

I think maybe I was confused about what you are saying. You said:

But then also:

In my mind, A being evidence of B means that you can (at least partially) infer B from A. But I'm guessing you mean "infer" to be something like "prove", and I agree the evidence isn't that strong.

I meant something closer to: 'we can't infer Y from X, because we'd still expect to observe X even if ¬Y.'

My impression is still that we have been somewhat talking past each other, in the way I described in the second paragraph of my previous comment. My core claim is that we should not look at the number of new EA groups as a proxy for growth in EA, since many new groups will just be a delayed result of earlier growth in EA, (as it happens I agree that EA has grown since 2015, but we'd see many new EA groups even if it hadn't). Whereas, if I understand it, your claim seems to be that as we know that at least some of the new groups were founded by new people to EA, we know that there has been some new EA growth.

Thanks for writing this post and crossposting it here on the EA forum! :)

This post is also posted on LessWrong and discussed there.

Scattered thoughts on this, pointing in various directions.

TL;DR: Measuring and interpreting movement growth is complicated.

Things I'm relatively confident about:

Things I am less confident about:

Interesting observations. I only have one thought that I don't see mentioned in the comments.

I see EA as something that is mostly useful when you are deciding how you want to do good. After you figured it out, there is little reason to continue engaging with it. [1] Under this model of EA, the fact that engagement with EA is not growing would only mean that the number of people who are deciding how to do good at any given time is not growing. But that is not what we want to maximize. We want to maximize the number of people actually working on doing good. I think that EA fields like AI safety and effective animal advocacy have been growing though I don't know. But I think this model of EA is only partially correct.

E.g., Once someone figures out that they want to be an animal advocate, or AI safety researcher, or whatever, there is little reason for them to engage with EA. E.g., I am an animal advocacy researcher and I would probably barely visit the EA forum if there was an effective animal advocacy forum (I wish there was). Possibly one exception is earning-to-give, because there is always new information that can help decide where to give most effectively, and EA community is a good place to discuss that. But even that has diminishing returns. Once you figured out your general strategy or cause, you may need to engage with EA less. ↩︎

I completely agree with this, thank you for writing it up! This is also an issue I have with some elements of the 'drifting' debate - I'm not too fussed whether someone stays involved in the EA community (though I think it can be good to check whether there have been new insights), I care about people actually still doing good.

This sentiment came up a fair amount in the [2019 EA Survey data](https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/F6PavBeqTah9xu8e4/ea-survey-2019-series-community-information#Changes_in_level_of_interest_in_EA__Qualitative_Data) about reasons why people had decreased levels of interest in EA over the last 12 months.

It didn't appear in our coding scheme as a distinct category, but particularly within the "diminishing returns" category below, and also in response to the question about barriers to further involvement in the EA community below that, there were a decent number of comments expressing the view that they were interested in having impact and weren't interested in being involved in the EA community.

It's probably unnecessary but I tried to think of a metaphor that would help to visualize this as that helps me to understand things. Here is the best one I have. You want to maximize the number of people partying in your house. You observe that the number of people in the landing room is constant and conclude that the number of people partying is not growing. (Landing room in this metaphor is EA). But that is only because people are entering the landing room, and then going to party in different rooms (different rooms are different cause areas). So the fact that the number of people in the landing room is constant might mean that the party is growing at a constant rate. Or perhaps even the growth rate is increasing, but we also learnt how to get people out of the landing room into other rooms quicker which is good.

That's one way to see it, but I thought that ideally you're supposed to keep considering all the possible "interventions" you can personally do to help moral patients. That is, if the most effective cause that matches your skills (and is neglected, etc etc) changes, you're supposed to switch.

In practice that does not happen much, because skills and experience in one area are most useful in the same area, and because re-thinking your career constantly is tiring and even depressing; but it could be that way.

If it was that way, people who have decided on their cause area (for the next say, 5 years) should still call themselves EAs.

Thanks for this post. One dataset not included in this analysis though is the number of EA groups. CEA's 2019 local EA group organizers survey data shows that EA has grown in terms of number of active groups significantly since 2015, but the number of new groups founded per year was pretty stagnant from 2015 to 2018. The screenshots below are taken from the survey report.

However, according to CEA's 2020 annual review, they tracked 250 active groups via the EA Groups survey, compared to 176 at the end of 2019. So I think EA, in terms of number of active groups, has actually grown a lot in 2020 compared to 2015-2019.

It would be great if CEA released a writeup on the data from the EA Groups 2020 Survey so we can have updated numbers for the two figures above.

Just to clarify, the EA Groups Survey is a joint project of Rethink Priorities and CEA (with all analysis done by Rethink Priorities). The post you link to is written by Rethink Priorities staff member Neil Dullaghan.

The writeup for the 2020 survey should be out within a month.

This isn't a safe inference, since it's just comparing the size of the survey sample, and not necessarily the number of groups. That said, we do observe a similar pattern of growth in 2020 as in 2019.

Ah yes, thanks for clarifying and sorry for the omission! Looking forward to that writeup. Will there be an estimate of the number of groups including outside of the survey sample for that writeup David?

An "estimate of the number of groups including outside of the survey sample" wouldn't quite make sense here, because I think we have good grounds to think that we (including CEA) know of the overwhelming majority of groups that exist(ed in 2020) and know that we captured >90% of the groups that exist.

For earlier years it's a bit more speculative, what we can do there is something like what I mentioned in my reply to habryka comparing numbers across cohorts across year to get a sense of whether numbers actually seem to be growing or whether people from the 2019 survey are just dropping out.

Thse graphs are surprising to me. They seem to assume that no groups were dying in these years? I mean, that's plausible since they are all pretty young, but it does seem pretty normal for groups to die a few years after being founded.

I think the first graph only counts the number of active local groups. It is true and pretty normal that some groups become inactive after a few years of being founded. And I think the second graph only covers active groups by the year they were founded, but I could be wrong.

It's a bit hard to eye-ball, but it seems that the blue line is just the integral of the red line? Which means that the blue line doesn't account for any groups that closed down.

Yeh these graphs are purely based on groups who were still active and took the survey in 2019, so they won't include groups that existed in years pre-2019 and then stopped existing before 2019. We've changed the title of the graph to make this clearer.

That said, when we compare the pattern of growth across cohorts across surveys for the LGS, we see very similar patterns across years with closely overlapping lines. This is in contrast to the EA Surveys where we see consistently lower numbers within previous cohort across successive surveys, in line with attrition. This still wouldn't capture groups which come into existence and then almost immediately go out of existence before they have chance to take a survey. But I think it suggests the pattern of strong growth up to and including 2015 and then plateau (of growth, not of numbers) is right.

Ah, great, that makes sense. Thank you for the clarification!

One other thing to bear in mind about growth in groups is that, as I discussed in my reply to Aaron, this metric may be measuring the fruits of earlier growth more than current growth in the movement. My impression that many groups are founded by people who are not themselves new to EA, so if you get people into the movement in year X, you would expect to see groups being founded some years after they join. This lag may give the false reassurance than the movement is still growing when really it's just coasting on past successes.

I've had many conversations about EA, and I've convinced at least a few people about the basic "give more to charity, and find better charities" idea (people who didn't seem to have an underlying compulsion to give). And I've definitely heard stories of people who became gradually more convinced by arguments related to e.g. longtermism or wild animal suffering, despite initial reluctance or commitment to what they were previously working on.

What would you count as a "conversion"? Someone who is initially resistant to one or more EA-related ideas, but eventually changes their mind? For any definition, I think examples are out there, though how common they are will depend on which definition we use.

One place to look for examples would be EA-aligned orgs that hire people who aren't particularly EA-oriented. Staff at these orgs are immediately exposed to lots of EA philosophy, but (in some cases I've heard of) only gradually shift their views in that direction, or start off not caring much but become more interested as they see the ideas put into practice.

I can try to track down people who I think this would describe and connect them with you. But first — what are you planning to do with the emails you receive? Would it be better for people to describe their "conversion" experiences on a Forum thread?

I suspect the EA Survey is the ideal place to ask this sort of question because selection effects will be lowest that way. The best approach might be to gather some qualitative written responses, try to identify clusters in the responses or dimensions along which the responses vary, then formulate quantitative survey questions based on the clusters/dimensions identified.

Thanks for this post. It made me think a lot about how EA could evolve. But I'm still puzzled about what sort of metrics we could use to measure growth or interest. I'll just add that, besides (as mentioned in the text) being hard to make sense of Google Trends data, I made a brief comparison with other terms related to EA, such as "doing good better" &"giving what we can" &"the life you can save", and it shows very different trends: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=effective altruism,giving what we can,doing good better,the life you can save,less wrong

Also, while Open Phil's donations to GiveWell have remained at a similar level, the amount they direct to the EA movement as a whole has grown substantially: